The Svetlana Boym Reader

Edited by Cristina Vatulescu, Tamar Abramov, Nicole G. Burgoyne, Julia Chadaga, Jacob Emery, and Julia Vaingurt

Bloomsbury, $39.95 (paper)

Immigrant life easily slips into melodrama. A whiff of blood sausage has me tearfully recalling the evenings when my grandmother cooked it for me. An unexpected “cześć,” or hello, overheard between two fellow Poles immerses me in involuntary memories, as I mourn greetings I shared with high school friends. I never actually liked blood sausage, or high school, and had rejoiced to leave them behind when I moved here. But for a moment, my unconscious fools me, and these recalled sensations compose themselves into a Hallmark card.

Most émigré writers gloss over such moments of weakness, depicting their attitudes and tastes as detached and worldly. Svetlana Boym (1959–2015), renowned scholar of comparative literature, was the rare thinker who leaned into them, in search for a more honest account of the uprooted life. “What might appear as an aestheticization of social existence to the ‘native,’” she wrote of such experiences, “strikes the immigrant as an accurate depiction of the condition of exile.” To be an immigrant is, paradoxically, not just to live in partial alienation from one’s new surroundings, but also to lose distance from the world one has left behind. It is only from such a position of humility, Boym further insisted, that illuminating generalizations about one’s experience—and about what this experience can teach others—can begin. As demonized and idealized depictions of migration loom large, Boym’s reflections on the fragilities of our memories in times of loss and transit seem more pressing than ever.

If Boym’s biography oscillates between persistence and transformation, those qualities are also blended in her writing itself.

Boym died of brain cancer at only fifty-six. She left behind many mourning colleagues, students, and readers, along with speculations about directions that her still-developing work would have taken. She began her academic career as a scholar of Spanish literature, turning later to the literature and culture of her native Russia, but it was her 2001 study The Future of Nostalgia that displayed the full range of her interests, winning her a broad audience. Through the prism of the decaying Soviet Union, Boym explored cosmopolitanism, exile, and cultural melancholy, moving readers from many geographical, intellectual, and linguistic backgrounds. Through readings of Soviet and post-Soviet art, literature, and everyday cultural production, she meditated on how we refashion ourselves in new countries, political systems, and languages, and on the ways we reach toward others across such cultural divides.

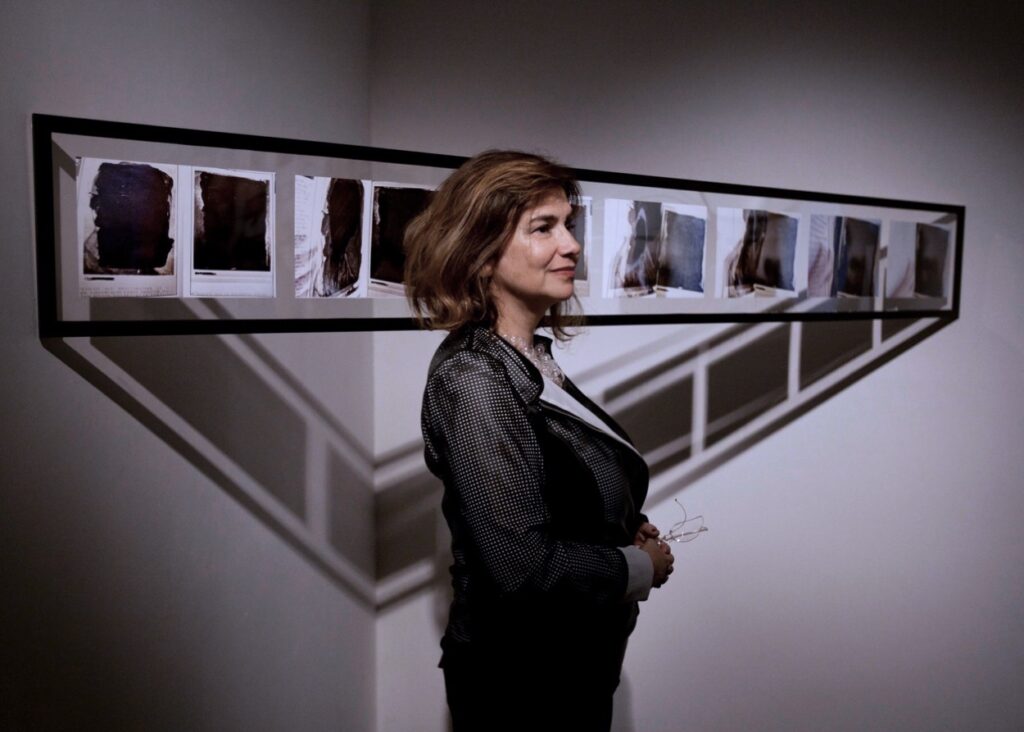

Those themes pervaded both her artistic and scholarly work, which The Svetlana Boym Reader now captures at its most centrifugal and outward-reaching. It argues for her lasting relevance not just as an academic, but as a cultural critic, artist, and philosophical essayist. Edited by six of her former students, the collection offers a panoramic view of Boym’s prolific output, from her graduate student years to her untimely death. True to the increasingly personal and creative bent of Boym’s writing, the Reader brings together excerpts from academic books and personal essays, scholarly overviews of her field, and Boym’s own visual artworks. Its eminent readability testifies both to what Boym’s work has given us, and to what we have irretrievably lost with her passing.

• • •

Boym romanticized her personal life, which she told through the prism of several alter egos, including a Facebook persona named Olga. But her biography is quite romantic even when stripped of embellishments. Born as Svetlana Goldberg, she studied Spanish in her home city of Leningrad before deciding, more or less on a whim, to leave the Soviet Union. She hatched her plan of escape with a young designer she met in a shopping queue, Constantin Boym.

There is a picaresque quality to Boym’s accounts of this sudden decision, but in truth the move seems to have been harrowing. It was preceded by a hasty marriage, endless bureaucratic difficulties, and a lingering fear that, once she had left Russia, she might never see her family again. As a Soviet citizen of Jewish descent, she was allowed to leave the USSR only for Israel; announced belatedly, her insistence on going west resulted in weeks of internment at a nameless refugee camp in Vienna before she was finally given an American visa. Once on the east coast, she soon divorced Constantin and found her first jobs under the adopted Spanish identity of Susana. Boym completed the master’s program in Spanish at Boston University, and then the PhD program in comparative literature at Harvard, where she stayed on to obtain tenure and an endowed professorship. As her career took off, she also moved away from academic writing and toward expression through personal essays, novels, and visual art.

If Boym’s biography oscillates between persistence and transformation, those qualities are also blended in her writing itself. On the one hand, it changed significantly over the years in style and focus; there is a bold, freewheeling associative quality to her later prose that her younger work clearly tempers. At first only a scholar of the writing of others, she gradually comes to see herself as a philosopher and creative writer in her own right. Her late writing also shows an increased drive to completeness, leaping to generalizations and epiphanies that her earlier work scrupulously avoids. If Boym’s first essays and books discuss the canon of modernist Russian poetry, the work she composed shortly before her death makes grand pronouncements about progress and freedom. In her last book, The Off-Modern (2017), she responds to the felt death of modernism itself, and our condition of perpetually mourning for it. “Modernity is our antiquity,” she aphorizes. “We live with its ruins, which we incorporate into the present.”

Boym pictures herself as caught between incompatible Western and Soviet ideological systems, trying to transform their mutual incoherence into a liberating source of self-discovery and imaginative play.

On the other hand, even as her style changes, Boym’s themes and methods remain startlingly consistent. Her approach can be best described as phenomenological—bridging the phenomenologies of careful reading with those of sensitive self-perception and interpersonal relation. In her creative work, which includes collages, photographs, and personal essays, Boym pictures herself as caught between incompatible Western and Soviet ideological systems, trying to transform their mutual incoherence into a liberating source of self-discovery and imaginative play. For Boym, the result is both a challenge and an opportunity. “The history of kitsch is as different in Eastern and Western Europe as is the history of modern art,” she explains. “What is countercultural discourse in one part of the world can turn into officialese in the other.” Her experiences of aesthetic suspicion, attraction, and rapture, always feel somewhat idiosyncratic and out of sync with surrounding reality. Suspicious of herself as an observer, but also ironic toward the confident tastes of her more firmly rooted peers, she also remains sympathetic toward the difficulties with which both the local and the globe-trotter face their particular subjective myopias.

In her academic writing, Boym diagnoses similar efforts at self-awareness in others, capturing the fantasies that political upheavals force individuals to embrace in order to make sense of their everyday lives. “The objects in the personal display cases of the communal apartments,” she writes in Common Places (1994) of the domestic environments she inhabited as a child,

are neither bare essentials nor merely objects of status and conspicuous consumption. If they do represent a need, it is first and foremost an aesthetic need, a desire for beauty met with minimal available means, or the aesthetic “domestication” of the hostile outside world. They are not about defamiliarization, but rather about inhabiting estranged ideological designs.

The objects Boym describes here function as affective life rafts. She is interested less in overt forms of protest than in the emotional labor of giving one’s life a sense of separateness, choice, and dignity. “Cultural myths,” she elaborates elsewhere, “are not lies but rather shared assumptions that help to naturalize history and make it livable, providing the daily glue of common intelligibility.” Despite their fantastical nature, it is only by exchanging such myths—and developing shared versions of them—that we can ever hope to communicate with each other.

This insistence on fantasy as at once never quite reliable and deeply formative structures Boym’s scholarly method at every level. On the scale of individual readings, it leads to masterful interpretations of novels, poems, and cultural situations that refuse to settle comfortably into a recognizably Marxist or liberal, progressive or reactionary conclusion. For Boym, indeterminacy is the most honest endpoint of reflection about our world and ourselves. “But what kind of love relationship is described in this text?” she asks at the end of a long account of Marina Tsvetaeva’s poems about a woman named Sonechka.

Is it a love affair with love, a romance with feminine lover’s discourse, or a love affair with Sonechka as a person? Can we really distinguish between them in any of Tsvetaeva’s relationships with women or men? Is the relationship between Marina and Sonechka sexual or Platonic? How does it participate in Russian cultural myths of love and sexuality?

This proliferation of unresolved questions is typical of Boym’s approach. She is not in the business of giving answers, even as she shows how much can hinge on them—philosophically, aesthetically, personally. Instead, for her, constant self-questioning lies at the heart of any interpersonal relationship, and any honest account of oneself.

• • •

Boym also insists that probing our cultural myths does not free us from their grasp; at most, it helps us look more acceptingly upon the affective impulses that move us. On one trip back to Russia, Boym wanders into a rusting children’s playground filled with toy avatars of the space race. She recalls climbing into model rockets as a child, pretending to be a young Yuri Gagarin. “With some trepidation,” she confesses,

I realize that we were the generation that was supposed to live in the era of Communism and travel to the moon. We did not fulfill our mission. Instead we were forced to confront the ruins of utopia; Soviet icons, recycled into souvenirs and totalitarian antics. The fairy tale of our childhood was deprived of a happy ending.

We acquire such myths before we know how to ironize or critique them, and though nebulous, they scaffold our emergent selves just as persistently as heavier Freudian traumas we diagnose more readily. They become the wellspring of the desires and attachments that make us reflect on our lives in the first place.

The satisfactions of nostalgic memory are fleeting substitutes for experiences of cultural coherence and unquestioned belonging.

Living amidst personal and collective shadows is not easy. The people in Boym’s writings often bump into their fantasies’ sharp edges or stumble over their sudden immateriality. Boym’s grandmother tells her endless, never quite consistent stories of the young trumpeter she was in love with—or was it the other way around?—who went missing in the Second World War. Boym herself scours the Viennese archives for an address, or just a passing mention, that could help her locate the refugee camp where she stayed before emigrating to America. She wonders at the mixture of irony and tenderness with which she finds herself recalling, and falling back into, the hopes and dreams of her Soviet childhood. While there is joy and intellectual playfulness to the collages of facts and dreams that her subjects put together, these imaginative efforts are undergirded by a sense of loss and betrayal. The satisfactions of nostalgic memory are fleeting substitutes for experiences of cultural coherence and unquestioned belonging. Intellectual maturity, in these instances, comes with the realization that creative autonomy has, as its obverse, a sense of cultural abandonment and hopelessness.

It is unsurprising, then, that the predominant theme of Boym’s late writing is nostalgia. For her the word names the difference between the actual past and the narrative future—between the conditions in which we once lived, and the traces they have left in our attempts to reflect on, or even restore, what once was. Nostalgic longing and fantasy, for Boym, constitute “the virtual reality of human consciousness that cannot be captured even by the most advanced technological gadgets.” They force us to recognize how many aspects of our experience remain inarticulable even to ourselves, let alone to others. In essays on friendship, which Masha Gessen has rightly described as some of her most beautiful and striking work, Boym finds in the relationships that emerge amid such unresolved self-interrogations a “diasporic intimacy” which hinges on “a particular balancing act between tact and touch.”

Reading Boym, one is struck, time and again, by her unremitting intellectual openness and curiosity. She was constitutionally incapable of parochialism. If her writing occasionally suffers from the blind spots that linger between her scattershot beams of expertise, it is also powerfully buffered by the lessons she gives us in navigating our never fully understandable, at times overwhelmingly cavernous surroundings. At her best, Boym perfects and immerses her readers in an infectious and persuasive, and surprisingly portable, way of noticing such precarious acts of imagination. This way of noticing is earnest and accepting, as well as illuminating, both when applied to a poem and after one has lifted one’s eyes from the printed page. Since The Future of Nostalgia first came out in 2001, many of us have known to look to Boym for explanations of that particular feeling. The Reader makes one realize how many other experiences—friendship, dislocation, and even death itself—Boym also helps us think about, unlike anyone else.

Editor's Note: Svetlana Boym contributed to the Boston Review February/March 1994 print issue, analyzing commercial advertising in the post-Soviet world. Read it here.