The Supreme Court’s recent decision in June Medical Services v. Russo surprised many observers anticipating a decisive step in dismantling Roe v. Wade. The case questioned the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that required abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a hospital within thirty miles of a clinic. The Court had already struck down an identical Texas law four years earlier, but Louisiana still expected to win, no doubt thanks to the Court’s new conservative majority. The state even asked the Court to undo decades’ worth of precedent in its argument that abortion providers should not be able to bring a constitutional challenge on behalf of their patients.

Like the abortion restrictions it will almost inevitably inspire, June Medical fits into an ongoing and long-term strategy to unravel abortion rights, a strategy that has sharpened our cultural divide on reproductive health.

But in the end, Chief Justice John Roberts sided with his liberal colleagues in invalidating the law and reaffirming that abortion doctors can challenge others like it. His concurring opinion reads like a love letter to stare decisis, the doctrine requiring the Court to honor its own precedents. Some predicted that regardless of what Roberts thought about abortion rights, he might save Roe because of his fidelity to precedent.

Now June Medical no longer looks like much of a win for abortion rights at all. Lower courts and lawmakers have begun taking a second look at restrictions that had already been blocked. No one is sure that the Supreme Court will do anything to stop them.

Where are the U.S. abortion wars likely to go next? The only way to understand what the most recent opinion means for Roe v. Wade is to look further back in time. Like the abortion restrictions it will almost inevitably inspire, June Medical fits into an ongoing and long-term strategy to unravel abortion rights, a strategy that has sharpened our cultural divide on reproductive health.

• • •

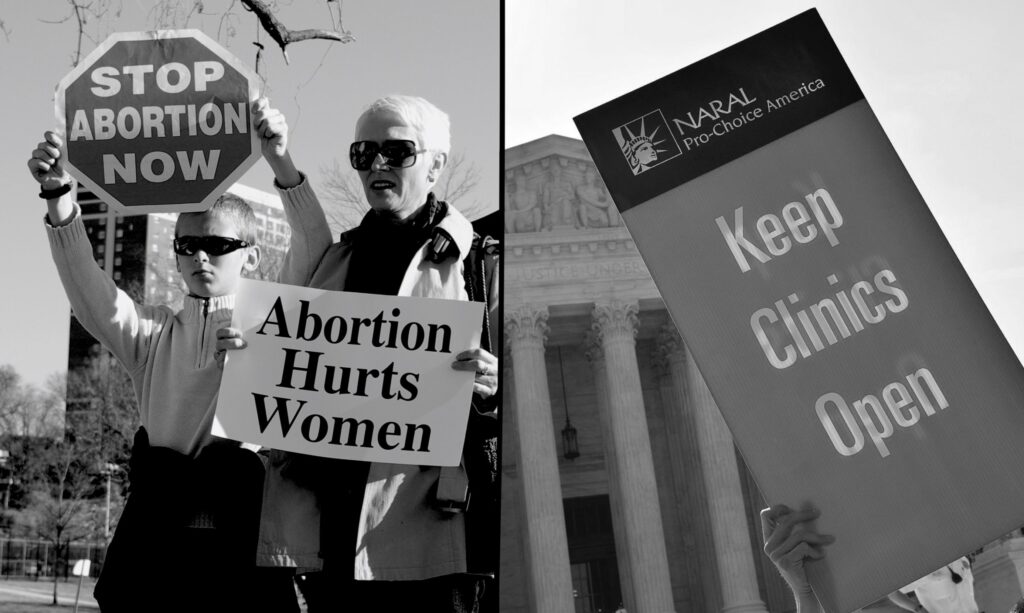

The claims made in the U.S. abortion struggle often seem to reflect “the clash of absolutes” famously described by legal scholar Laurence Tribe in his 1990 book of that name. Supporters of legal abortion fight for a right to choose while abortion foes defend a right to life for the unborn child. These arguments seem to reflect what legal theorist Ronald Dworkin called “rights as trumps”—constitutional protections that prevail over other policy considerations or even the preference of voters.

The distinction between rights- and policy-based arguments is conceptually valuable, especially when we seek to understand the contemporary U.S. abortion conflict.

One might be tempted to describe the impasse we face today as arising because those on each side of the abortion debate believe that they defend a right that outweighs any competing concern. To be sure, such rights-based arguments remain an important part of the discussion. But in recent decades, the core terms of the legal debate about abortion in the United States have changed in ways we have rarely appreciated. Between 1973 and 2019 the conflict has centered not so much on laws criminalizing abortion outright as on the quest for incremental restrictions designed to undermine Roe v. Wade. And with this change in emphasis, the struggle has increasingly turned not only on rights-based trumps but also on claims about the policy costs and benefits of abortion for women, families, and the larger society.

This change was never straightforward or absolute. Indeed, before Roe, those backing abortion rights often pointed to what they saw as the desirable consequences of legalization, such as fewer deaths from botched illegal abortions. Roe v. Wade itself spoke not only about a constitutional privacy right that encompassed a woman’s abortion decision but also about the harms that could follow if women had to carry undesired pregnancies to term. Nevertheless, the distinction between rights- and policy-based arguments is conceptually valuable, especially when we seek to understand the contemporary U.S. abortion conflict.

When stressing constitutional rights, those on either side have suggested that a particular right is priceless, grounded in the constitutional order, and deserving of protection irrespective of its costs and benefits. On the one hand, abortion opponents have often argued that the right to life protects a fetus or unborn child no matter how women come to be pregnant—and regardless of what would happen after a child was born. The idea of a right to choose, on the other hand, suggests not only that women should have the liberty to decide for themselves when to have a child but also that women should get the final say about why a decision is the right one.

By contrast, when making arguments about the costs and benefits of abortion, activists on either side have primarily discussed not what the Constitution allows but whether legal abortion was socially, culturally, personally, and medically desirable or justified. Consequence-based arguments put greater emphasis on the reasons that individuals might choose or oppose abortion rather than on individual liberty from the state.

How and when did the terms of the abortion debate change, and what has it meant for the larger abortion conflict? As soon as the Court handed down its decision in Roe in 1973, American pro-lifers championed a constitutional amendment that would ban abortion outright—even in states where voters supported reproductive rights. This constitutional amendment became the sole preoccupation of an otherwise fractious antiabortion movement.

When making arguments about the costs and benefits of abortion, activists on either side have primarily discussed not what the Constitution allows but whether legal abortion was socially, culturally, personally, and medically desirable or justified.

But when the campaign stalled in the mid-1970s, lawyers working with organizations like the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) and Americans United for Life (AUL) proposed a temporary solution: incremental restrictions that made abortions harder to get. These regulations required a different defense than the absolute prohibitions pro-lifers had long defended. After all, many of these statutes, such as abortion funding bans, did not clearly advance a right to life since they did not outlaw a single abortion. Instead, these laws created various obstacles that women had to clear.

How could abortion foes defend their new plan of attack? Rather than invoking fetal rights, members of AUL and NRLC began justifying these laws by highlighting their supposed benefits. For example, in championing funding bans like the various iterations of the 1976 Hyde Amendment, which bars the use of federal funds to pay for abortion except in certain limited cases, pro-lifers heralded the benefits to taxpayers with conscientious objections to abortion rather than directly singing the praises of a right to life. In court, antiabortion lawyers similarly focused on claims about the facts. When the Supreme Court defied expectations by upholding the Hyde Amendment, new opportunities for abortion opponents emerged. Even if the justices still recognized abortion rights, the antiabortion movement could make progress by trying to redefine what abortion in the United States was really like.

• • •

In the following decade, the fight to define the facts about abortion became even more important to the antiabortion movement. When Ronald Reagan won the 1980 election and Republicans swept into power, antiabortion activists hoped that they could finally change the text of the Constitution. But there were not enough votes for a constitutional ban that pleased most abortion opponents. Instead, antiabortion activists had to choose one of two alternatives. The battle about which was better tore the movement apart. One option, a federal law functionally banning abortion, appealed to absolutists but seemed likely to fall in the Supreme Court. An alternative—a constitutional amendment allowing, but not requiring, the states to ban abortion—pleased antiabortion pragmatists but struck absolutists as an unprincipled cop out. By 1983 these internal divisions forced pro-lifers to give up on a constitutional amendment.

Abortion foes could pass and defend restrictions that chipped away at abortion rights, and, by aligning with the GOP, could change the membership of the Supreme Court. Over time, this strategy could ensure that the Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

The leaders of the antiabortion establishment believed that they had already identified an alternative mission: abortion foes could pass and defend restrictions that chipped away at abortion rights, and, by aligning with the GOP, could change the membership of the Supreme Court. Over time, this strategy could ensure that the Court overturned Roe v. Wade. And in defending incremental restrictions, pro-lifers often emphasized the costs of abortion—and the benefits of certain laws restricting it.

Abortion rights supporters had to develop an effective response to this concerted strategy. At times feminists detailed how access to abortion had helped women, families, and communities. And abortion rights attorneys worked to show that seemingly innocuous restrictions could create obstacles as insurmountable as a law that criminalized abortion outright.

In some cases, groups on either side of the abortion conflict still prioritized claims about fundamental rights, but questions about the reality of abortion in the United States continued to dominate discussion, ultimately forging a strategy that saved abortion rights. In looking for a vehicle to reach the newly conservative Supreme Court, larger antiabortion groups working in the late 1980s and early 1990s insisted that abortion hurt teenagers and decimated marriages. In the name of preserving the traditional family, antiabortion groups promoted laws requiring pregnant people to involve husbands and parents.

Ironically, claims about the benefits of abortion transformed efforts to defend abortion rights. While their opponents emphasized arguments about the costs of abortion for the family, the ACLU, the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (now commonly known as NARAL Pro-Choice America), and Planned Parenthood fused claims about the benefits of abortion with arguments about equal treatment for women. Abortion rights attorneys emphasized that restrictive laws stripped young women of emerging opportunities to pursue a career or education. Related arguments helped convince the Court to continue recognizing a constitutional right to abortion. In the early 1990s, after the Supreme Court agreed to hear its next abortion case, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, ACLU attorneys made claims about the benefits of legal abortion for women a crucial part of the case for preserving legal abortion. These arguments spotlighted the relationship between abortion and equality between the sexes.

This plan seemed to pay off in 1992 when the Court retained what it called the “essential holding” of Roe. The Court’s decision in Casey increased the importance of arguments about the costs and benefits of both abortion and laws restricting it, holding that restrictions would be unconstitutional only if they unduly burdened those seeking an abortion. An undue burden existed when a law had the purpose or effect of creating a substantial obstacle to abortion access. After Casey, those on both sides battled to define the purpose and effects of abortion laws. And abortion foes increasingly spotlighted claims about the benefits and harms of abortion itself.

• • •

Later, in the mid-1990s, with a sympathetic president, Bill Clinton, in office, groups like NARAL and Planned Parenthood finally took control of the agenda by emphasizing claims about the health benefits of abortion and lobbied for its inclusion in national health care reform. Organizations of nonwhite feminists, including SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, called for a different approach to the relationship between abortion and health care, demanding reproductive justice, rather than simply a right to choose, for all women. Instead of focusing on freedom from government interference with reproductive decisions, this reproductive justice approach demanded for women the power and resources to have children, not have children, or to parent the children they already had.

Gonzales reflected how deeply the abortion divide had grown. Opposing sides could not agree even on the basic facts about abortion.

The narrower focus on health benefits nevertheless laid the groundwork for a new and effective attack on abortion rights. Grassroots pro-lifers believed that neither courts nor legislatures would ever deliver meaningful change; some worked in crisis pregnancy centers to prevent individual women from ending their pregnancies. Conservative Christian lawyers in organizations like Liberty Counsel and the American Center for Law and Justice invested more in cases involving the freedom of speech and religion of conservative Christians than in any effort to convince the Court to overturn Roe.

But attorneys in the antiabortion establishment used claims about the costs of abortion to outline a new plan of attack: insisting that abortion caused psychological and physical damage. This attack served two purposes. Abortion foes believed that the Supreme Court had hesitated to pull the trigger because the justices feared a backlash. Antiabortion leaders believed that public support for legal abortion would collapse if the procedure hurt women. And the Court had preserved abortion rights because women relied on the ability to decide when and how to have children. But if relying on abortion was foolhardy or hazardous, there might be no reason to save abortion rights again.

As both sides disputed the costs and benefits of abortion, areas of disagreement multiplied. By the later 1990s—as part of a long struggle over a specific procedure, dilation and extraction, that pro-lifers called “partial-birth abortion”—the two movements not only contested the effects of the procedure but also asked who had the authority to measure them. These disputes shaped Gonzales v. Carhart, the Court’s 2007 decision to uphold a federal ban on partial-birth abortion.

Gonzales reflected how deeply the abortion divide had grown. Opposing sides could not agree even on the basic facts about abortion. Gonzales had given legislators more latitude to regulate when a scientific question appeared uncertain. After the Court’s ruling pro-lifers tried to generate scientific uncertainty, and after Republicans’ impressive results in the 2010 midterm election, state legislatures passed a stunning number of regulations. Both sides responded by increasingly questioning the integrity and motivations of those with whom they disagreed. By 2016, when Republican Donald Trump replaced the Court’s longtime swing justice, Anthony Kennedy, it seemed inevitable that one of these restrictions would be the one the justices used to overturn Roe.

After the arrival of Brett Kavanaugh on the Supreme Court in 2018, antiabortion strategies have continued to put facts—or at least, arguments about the facts—center stage. By the time Kavanaugh was confirmed, antiabortion lawmakers had banned abortion at twenty weeks based on highly disputed claims about the timing of fetal pain; in seventeen states these laws are still on the books. Abortion foes, meanwhile, have advocated for laws banning the most common and safe procedure after the first trimester, dilation and evacuation, by claiming that there was uncertainty about whether other methods could serve as a safe alternative. Several states introduced mandatory counseling laws connecting abortion to breast cancer, infertility, and suicidal ideation.

Even when dissenting antiabortion groups demanded more aggressive action, factual questions remained central. In 2019, as states banned abortion at six weeks, legislators relied on disputed arguments about when doctors could detect a fetal heartbeat—and what that heartbeat meant to constitutional disputes about abortion. And early on during the COVID-19 pandemic, some conservative states banned abortions in implementing stay-at-home orders. Governors imposing these bans did not claim that there was no right to abortion. Instead, lawmakers focused on the facts, claiming that abortions used up valuable personal protective equipment and hospital beds. As states rushed to reopen, these orders have been lifted, but arguments about the reality of abortion in the United States have remained important.

Strategies focused on the reality of abortion have remained important because they seem to help the antiabortion movement. By focusing on the facts, sophisticated antiabortion groups have eroded protections for legal abortion without forcing the Court to say anything explicit about abortion rights. Poll after poll has suggested that American majorities do not want Roe overruled and support the idea of abortion rights (even while the respondents seemed receptive to a wide variety of abortion restrictions). Many might be angered by a ruling denigrating reproductive rights or embracing protection for fetal life. By contrast, if the Court focuses on contested factual claims, few might understand what the justices had really done. And by focusing on the facts, abortion foes can slowly but steadily chip away at the foundation of Casey and Roe. After all, the Court has preserved abortion rights partly because access to the procedure helped equal citizenship. Antiabortion groups hope to produce evidence that abortion actually undermined equality for women, making them sick, depressed, and weak.

The abortion restrictions that are most likely to land at the Court in the aftermath of June Medical will probably share this focus on facts. Lower court judges are taking a second look at laws banning dilation and evacuation, the most common procedure after the first trimester, or forcing patients to undergo additional, risky procedures. Until now, these laws have not fared very well. But antiabortion leaders insist that the need for dilation and evacuation is medically uncertain. And when there is scientific uncertainty—real or manufactured—lawmakers may claim more power to act. Similar laws, like those banning abortion after twenty weeks, rely on disputed claims about the timing of fetal pain and the dangers of later abortions for women.

Other states dispute the facts about why patients choose abortion. Tennessee and Mississippi have joined those banning abortion for reasons of race, sex, or disability, asserting that the abortion rights movement began to advance a eugenic agenda (and that patients today often have invidious motives).

When there is scientific uncertainty—real or manufactured—lawmakers may claim more power to act.

June Medical will make these sorts arguments even more appealing to the antiabortion movement. The four dissenting justices seemed to accept arguments that abortion harms women. Louisiana had argued that doctors should not have standing to challenge abortion regulations because doctors could not be trusted to care about their patients. The dissenters agreed. In an opinion joined by four justices, Justice Samuel Alito described what he saw as a “glaring” conflict of interest between patients and providers, suggesting the latter cared more about convenience and money than patient safety. Chief Justice Roberts invalidated Louisiana’s law because it was “word-for-word identical” to one the Court had just struck down, but he had bought into the argument that women needed protection from abortion in 2016. Nothing in June Medical suggests that he has changed his mind. Given the chance to rule on a different restriction claimed to protect women, the chief justice will likely vote to roll back abortion rights even more.

Even Roberts’s praise of precedent seems hollow in retrospect. His opinion redefined the undue burden test, the rule that dictates the constitutionality of all abortion regulations. In 2016 the Court held that in defining an undue burden, judges had to weigh the benefits and burdens of an abortion law. That meant that a pointless law might be unconstitutional even if the burdens it created were only somewhat onerous. And the courts had to take a hard look at the evidence in a case rather than deferring to what state legislators said about scientific data.

Roberts’s opinion changed that. When there is no majority opinion for the Court, the narrowest opinion for the majority outcome controls. In June Medical, that means Roberts’s concurrence. The chief justice held that the benefits of abortion regulations do not have to be considered; as a result, laws with specious justifications (or no justification at all) will stand as long as the Court does not think they are especially burdensome. And he suggested that when lawmakers argue that an issue is scientifically uncertain, the Court should typically take them at their word. Abortion opponents have been hard at work manufacturing or identifying scientific uncertainty about everything from the dangers of abortion to the need for specific techniques. June Medical did nothing to undermine the leading strategy to decimate abortion rights; today that tactical plan looks smarter than ever.

• • •

June Medical thus serves as a bleak reminder of how profound our abortion politics will remain, regardless of what happens to Roe. Many have speculated that if the Court overturns Roe, the conflict may eventually deescalate. Justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg have both argued that had Roe been decided differently (or if the Supreme Court had stayed out of it altogether), the issue would have been less divisive. But the recent history of the abortion conflict gives us reason to be deeply skeptical of claims that overturning Roe will make the abortion battle less polarized, even in the long term.

The abortion debate has always reflected other battles that define American culture—over health care, the needs of the poor, the role and size of government, the fortunes of the family, and the value and meaning of scientific expertise.

Indeed, a focus on incremental restrictions has done nothing to make the conflict less bitter. Opposing activists still hold irreconcilable foundational beliefs about the Constitution. Debating the policy consequences of abortion has not and will not convince many to alter their basic values. Nor, in all likelihood, would a decision overturning Roe make any difference to the constitutional absolutes defended by either side. Many abortion foes would not be completely satisfied with anything less than the recognition of a right to life that would require, rather than allow, states to criminalize abortion. If Roe is overturned, abortion rights supporters would simply resume the fight for recognition of a sweeping right to choose in state legislatures and in state and federal courts. Activists on both sides have not only fought for different constitutional principles; they have also believed in irreconcilable narratives about abortion and issues related to it.

The time has come to reconsider why we have arrived at such an impasse in the abortion debate. The stakes are high, for the abortion debate has always reflected other battles that define American culture—over health care, the needs of the poor, the role and size of government, the fortunes of the family, and the value and meaning of scientific expertise. We should expect future discussions of abortion to be no less fraught. Regardless of the fate of Roe v. Wade, the legal history of abortion will still tell a story about what kind of country the United States has been and will become.

Editors’ Note: This essay is adapted from the author’s book, Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2020).