Wrong: A Critical Biography of Dennis Cooper

Diarmuid Hester

University of Iowa Press, $39.95 (paperback)

The idea of a transgressive writer is a bit hard to fathom in the current moment, but that’s precisely what Dennis Cooper was. In the 1980s and ’90s, he rose to counterculture fame with his brilliant, dark novels about gay teens, gay psychopaths, gay drug addicts, and gay sex workers. This earned him comparisons to both Bret Easton Ellis and schlock horror writer Poppy Z. Brite, which indicates something of the challenge readers had categorizing his work.

Unless you’ve already spent time with Cooper’s violent, sexy explorations of desire, power, and subjugation, his frustration at being grouped according to “gay content” is hard to fully appreciate.

But by 2011 he was exhausted—or, at least, over it. In a Paris Review interview, Ira Silverberg asked Cooper about being accused of “propagating negative stereotypes of gays” in his novels, and Cooper’s answer was direct:

Because I was gay and my books were considered to have gay content by people who insist on categorizing things in that identity politics–based way, and because I wasn’t using my work to promote the many wonderful aspects of being gay, I was treated as a turncoat. Luckily, in the mid-nineties, more mainstream gay men stopped reading novels or thinking that books mattered, and that noise started moving into the background.

Partly, Cooper was limning the difference between his writing and that of early Lambda Award winners such as Alan Hollinghurst or Edmund White, whose themes and prose style tend toward stately longing and exuberant epiphany. Instead, Cooper aligns with the decidedly less deified “Downtown Scene,” a diverse (in every sense) group of writers that includes Kathy Acker, Gary Indiana, Patrick McGrath, Eileen Myles, Darius James, Miguel Piñero, Lynne Tillman, and David Wojnarowicz, all of whom once lived on New York’s Lower East Side. But in the Paris Review interview, Cooper sounds more like a marginal misanthrope than a celebrated artist doing press for one of his best-received books, The Marbled Swarm (2011), and on the verge of a decade in which he successfully transitioned into screenwriting while collaborating on a series of strange, alluring novels-in-GIFs.

Unless you’ve already spent time with Cooper’s violent, sexy explorations of desire, power, and subjugation, his frustration at being grouped according to “gay content” is hard to fully appreciate, but that impression can be swiftly overturned. Here, for instance, are the opening paragraphs of his 1985 short story “Wrong”:

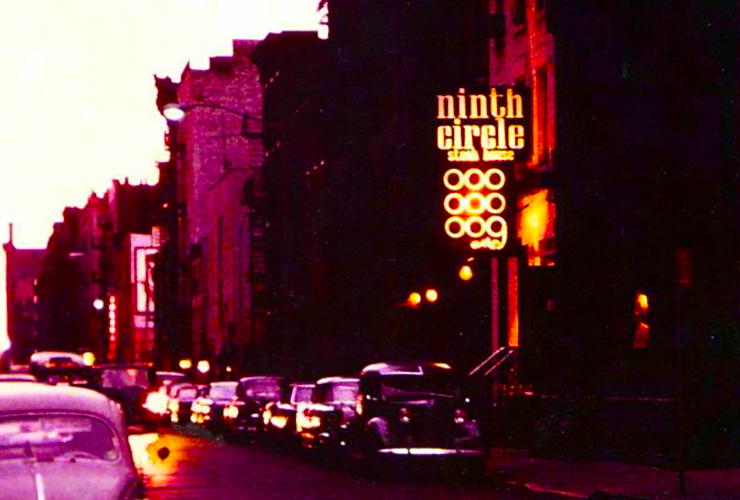

When Mike saw a pretty face, he liked to mess it up, or give it drugs until it wore out by itself. Take Keith, who used to play pool at the Ninth Circle. His crooked smile really lights up the place. That’s what Mike heard, but it bored him. ‘Too obvious.’Keith was a kiss-up. Mike fucked him hard, then they snorted some dope. Keith was face first in the toilet bowl when Mike walked in. Keith had said, ‘Knock me around.’ But first Mike wanted him ‘dead.’ Not in the classic sense. ‘Passed out.’

The brutality only intensifies from there. After a few more murders, a blasé Mike commits suicide—“Once you’ve killed someone, life’s shit. It’s a few rules, and you’ve already broken the best”—and then his body, bobbing in the Hudson, is spotted by a group of tourists, including a teenager named George. George then goes to the Ninth Circle, where he is picked up by a different S&M serial killer (this one owns a Lichtenstein), beaten to death, and then wanders Greenwich Village as a ghost. George returns to his hostel to profess fondness for his roommate, but is no more articulate or enlightened in his ethereal form: “‘Shit,’ and he started to tremble, ‘I like you. What can I say? Or not you, but you’re all I have. I blew it.’”

George’s final lines are a case study in the syntax of cringe, but generally speaking, Cooper’s writing is not gritty or stark so much as cool, in the sense of impassive as well as in the know—the Ninth Circle was a real gay bar (and “steakhouse”) in the Village with a reputation for hustlers and snortables. The violence in “Wrong” is doing real work, allowing Cooper to explore the structures that enable violence against gay men, or at least refuse to prevent it, posthumously elevating teen deaths from banal to poignant but never protecting those same teens when they’re alive. George’s murder isn’t even unique within this short story.

Generally speaking, Cooper’s writing is not gritty or stark so much as cool, in the sense of impassive as well as in the know.

So to say that a story like “Wrong” features “gay content” is not inaccurate so much as beside the point, like claiming that Carl Theodor Dreyer’s classic film The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) is about the challenges that women face in the workplace. Indeed, Cooper turns that frustration into a brilliant narratological tic in the very book he was promoting when he spoke to the Paris Review. In The Marbled Swarm, the sadist-cannibal (or is he?) narrator speculates about what he might’ve done “were I gay and not the creep to whom you’ll turn the other cheek soon enough.” Still, one comes away from the interview with the sense that Cooper has more or less given up on a wide, sophisticated reception.

A recent biography aims to change this. Lately, Cooper seems reenergized, building upon the success of his film Permanent Green Light (2018) by announcing his first new novel in a decade. I Wished, forthcoming in 2021, will return to the series of novels that brought him into the mainstream press in the 1990s. But how that novel is greeted may well depend on how many people read Diarmuid Hester’s Wrong in the meantime.

Drawing on extensive archival research and the more overtly political strands of queer theory, Hester disentangles Cooper from the Downtown Scene in favor of a sustained focus on the formation of his individual, idiosyncratic taste and style. Hester structures each chapter as a self-contained argument, beginning with a few of Cooper’s major influences, then progressing into studies of his major works. In each, life events and Cooper’s interpretations of literature, conceptual art, and film are interwoven with cultural theory and the literary tectonics of the day.

As a result, Wrong is engrossing in excerpt, and even readers who are new to Cooper will be captured by the opening chapter. In it, Hester explores Cooper’s first encounter with John Baldessari’s disconcerting series of suburban photo collages—including the self-portrait, Wrong (1967), which gives title to both Cooper’s story and Hester’s biography. Baldessari’s arch, awkward image has the artist standing directly in front of a tall palm tree that’s in the yard of a nondescript tract house. Beneath the image is the inscription, both title and critique, “WRONG.”

Baldessari’s piece thus overturned the conventions of traditional photography while satirizing the postwar American dream, but when the young Cooper saw it first at LACMA, he may have been most startled by the artwork’s uncanny familiarity—how it seemed to echo his experience growing up and his sense that, regardless of appearances, life in the California suburbs could indeed be very wrong.

Hester goes on to describe Cooper’s affluent but unstable upbringing—marked by an uncle’s suicide and his mother’s violent alcoholism—with a light juxtapositional touch, never suggesting a direct correlation between life event and work of art but revealing similar shapes and obsessions. For instance, we learn that when he was eleven years old, Cooper and a friend were building a fort when the friend accidentally split Cooper’s head with an axe, resulting in a prolonged hospital stay.

During Cooper’s convalescence, the friend who bludgeoned him wouldn’t talk to him or even look at him. He did send Cooper long letters, however, announcing that he wanted to kill himself as a kind of punishment for what he’d done. He also wanted Cooper to beat him and torture him as revenge; ‘I didn’t, but I found these letters very erotic. It was the first time I had seen such things in written form, and I used to fantasize about hurting and torturing him, using the letters as pornography and justifying my fantasies to myself because he had issued the invitation.’

The reasons why this friend couldn’t face Cooper are less important to Cooper (and Hester) than the epistolary relationship that that inability produced. Felicitously, this heady mixture of violence, desire, and insufficient adolescent self-knowledge is present in all of Cooper’s published writing. And although Hester doesn’t explicitly ask us to consider Baldessari’s image here, it’s hard not to do so, since it has appeared in the book only a few pages earlier. Baldessari’s obscured figure—facing us but without our being able to see his face—“invites” another kind of fantastic projection, as well as a milder and more foreboding indication that all is not quite right in sunny suburbia.

Hester explores Cooper’s affluent but unstable upbringing with a light touch, never suggesting a direct correlation between life and art but revealing similar shapes and obsessions.

Which is also to say that Cooper’s “Downtowniness” was always a function of distribution and vibe more than geography and assiduous social commitment, and Hester helps to make that clear. While Cooper published “Wrong” in Joel Rose and Catharine Texier’s influential magazine Between C&D—as in, between Avenues C & D on the Lower East Side, but also “between coke & dope,” among other opportune acronyms—and his novels were brought to the UK by Downtown-evangelizing press Serpent’s Tail, he was already an influential poet, editor, and curator before landing in New York in 1983. And even though Cooper held the launch party for his first novella, Safe (1984), at the storied Limelight megaclub in Chelsea, Cooper was disappointed by the increasingly hetero complexion of the New York literary scene and exhausted by its many social obligations. Following a boyfriend, Cooper decamped for Amsterdam a year later.

More to the point, where many Downtown writers adapted the strategies of San Francisco’s explicitly gay, Marxist New Narrative movement—writing (sometimes fictionalized) diary-narratives about their own and their friends’ lives, explicitly imagining those friends to be their readers, alternating between ecstatic sexuality and detailed observations about other artworks and philosophy—Cooper’s own life and loves never appear in a manner that feels trustworthy, much less as a testament to an embattled community. Put another way, I expect a biography of Eileen Myles to look a lot like Myles’s stories, whereas even readers very familiar with Cooper’s work are likely to be surprised by Hester’s biography.

One of Hester’s most thrilling sections explores an elaborate hoax from the early aughts, which took place while Cooper was working on his novel about school shootings, My Loose Thread (2002). “JT Leroy” claimed to be a homeless HIV-positive fifteen-year-old hustler from San Francisco, writing down his experiences before his looming death—but was, in fact, thirty-something New Yorker Laura Victoria Albert. Leroy’s early novels, Sarah (2000) and The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things (2001)—powered by press about the author’s tragic story—attracted endorsements from megastars such as Winona Ryder and Bono. But as Hester reveals, the scam really started with desperate phone calls from “Leroy” to Cooper, in which the fictitious boy claimed that Cooper was his hero. Cooper was, understandably, drawn in:

Many of Cooper’s friends had tested positive for HIV in the ’80s and ’90s and had passed away soon afterward, so this was devastating news for him. That a mere teenager should have to experience the ravages of AIDS was beyond heartbreaking. . . . Cooper was especially predisposed to nurturing the talents of promising young writers (particularly those who were in need of emotional as well as creative support), so in addition to managing [Leroy’s] unpredictable moods, Cooper also encouraged him to develop his writing skills and sent him books he thought might help him. One of these was User: A Novel (1994) by Cooper’s friend Bruce Benderson, a writer and translator who was well known on the Downtown New York scene.

With Benderson, Albert repeated the template of her success with Cooper, and thereafter with an increasingly prominent group of editors, agents, actors, and rock stars. Eventually Albert recruited the help of her husband’s teenage sibling, Savannah Knoop, who would wear a Warhol wig so that the pair could appear in public as Leroy (Knoop) and Leroy’s protective manager (Albert). Perhaps most astonishing is that it took until 2006 for the ludicrous deception to be publicly exposed, at which time the pair was pilloried.

Even before the final revelation, Cooper had been profoundly wounded when Albert/Leroy used an image of Cooper’s childhood friend and first love, George Miles—who had committed suicide in 1987—as “Leroy’s” author photo. Later, Albert/Leroy claimed that they had inspired much of Cooper’s writing, a preposterous idea from a figure who claimed to not have been born until after the publication of Cooper’s third novel. But it was enough to push Cooper to renounce the nonfiction study of school shootings that he had begun, and to fictionalize the phenomenon as a way of taking the child perpetrators themselves seriously.

Contrasting My Loose Thread with Leroy’s maudlin Harold’s End (2003), Hester delicately maps the way Albert violated Cooper’s personal life and professional contacts, as well as Albert’s cruel manipulation of a community grieving the HIV epidemic. But we’re also encouraged to consider the relationship between the culture’s frothy appetite for Leroy’s story and its refusal to reckon with the conditions that create actual lives like “his.”

Making the surprising choice to spend four chapters exploring Cooper’s early, often overlooked poetry, Hester argues for Cooper as a poetic talent who deserves greater recognition.

Wrong’s overarching arguments are implied but no less compelling. Making the surprising choice to spend four chapters exploring Cooper’s early, often overlooked poetry, Hester argues for Cooper as a poetic talent who deserves greater recognition. First, he distinguishes Cooper’s “poetics of dissociability” from the Venice Beach scene that fostered him, and then the second-generation New York School poets whom Cooper admired. Next, Hester reads Cooper’s correspondence with figures from the New Narrative movement and Washington, D.C.’s Mass Transit scene as providing differing but influential models for queer radicalism. Finally, he examines the homophobic reception of Cooper’s writing by two major figures of the previous generation of poets, Ed Dorn of the Black Mountain poets and former Paris Review poetry editor Tom Clark. Conspicuously after Cooper reneged on publishing a collection of Clark’s poetry (Cooper’s press had folded for lack of funds), Clark and Dorn named Cooper a recipient of their cruel “AIDS Award for Poetry” in a 1983 issue of Dorn’s magazine Rolling Stock. Other “recipients” included Allen Ginsberg, Steve Abbott, Robert Creeley, and Clayton Eshleman.

Hester patiently contextualizes throughout, giving a clear sense of how Cooper’s literary sensibility was formed through (but distinct from) these friends and fights. In one especially audacious moment, Hester argues that Cooper’s nascent anarchism drew directly from Frank O’Hara, which has been previously hard to detect because critics have failed to appreciate O’Hara’s admiration for counterculture philosopher Paul Goodman. Beginning with Goodman’s “anarchistic belief in the inviolability of individual uniqueness and the practicality of small-scale community building,” Hester leads us through O’Hara’s skeptical epithalamion, “Poem Read at Joan Mitchell’s,” before arriving at Cooper’s prose poem “A Herd.”

Without doubt more sensational than O’Hara’s ‘Poem Read at Joan Mitchell’s’ and utterly distinct from the earlier work in tone and technique, ‘A Herd,’ Cooper’s long poem from [The Tenderness of the Wolves (1982)] nonetheless presents a critique of communion and the common that is comparable with O’Hara’s and evokes the devastating—even murderous—erasure of individuality that a pursuit of intersubjectivity may engender.

Sadly, “A Herd” didn’t make the cut for the narrow The Dream Police: Selected Poems, 1969–1993 (1996) that Grove Atlantic currently has in print, a collection which favors Cooper’s shorter, more sardonic poems such as “First Sex” (1979), which begins:

This isn’t it.I thought it would belike having boned a pillow.I saw myself turningover and over in lustlike sheets in a dryer.

Cooper has a gift for youthful awkwardnesses that disclose inner struggle, and many of Hester’s best readings unpack the ontological questions buried beneath the shrugs and slang that create that “syntax of cringe.” Where “First Sex” seems to be about the disappointment of a long-awaited lay, Hester goes deeper: “with the obstruction of understanding between the self and the other and in the absence of a coveted intersubjective experience, the speaker is isolated and alone with his fantasies.” Radiating outward, Hester wisely aligns these moments with a rebellious strain of U.S. modernism practiced by pioneering lesbian novelist Djuna Barnes. Which is to say, en route to uncovering the literary precedents for Cooper’s style and politics, Wrong makes a strong case for an expanded edition of his poetry.

Cooper speaks powerfully—if obliquely—to our era of deep suffering and infuriating indifference, but because he doesn’t expressly implicate capitalism, homophobia, or structural racism, he often misses out on an audience that deserves him.

Hester’s interest in Cooper’s ecumenical anarchism gains momentum in the chapters about his more recent activities. In a brilliant reading of Cooper’s long-running blog—censored by Google in 2016, sparking outrage from many critics who otherwise don’t discuss him—Hester attends to the now-lost comments sections, where Cooper and the “distinguished locals” had wide-ranging conversations that built an “anarcho-queer commons.” To Hester, the blog resembled the very scene that birthed Cooper, especially as described by the late José Esteban Muñoz, whose reflections on LA punk “were uncannily apropos.” In particular, Hester sees Cooper crafting a digital version of what Muñoz called “circuits of being-with, in difference and discord, that are laden with potentiality and that manifest the desire to want something else.” It’s a shrewd extension of theory that helps to understand Cooper’s transition into “.gif novels” and film in the Internet era, creating more and more openings for manifesting those desires.

But falling into those openings often leads away from Cooper himself. The only aspect of Cooper’s remarkable and varied career that does not receive careful treatment are his magazine articles from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, the best of which are collected in Smothered in Hugs: Essays, Interviews, Feedback, and Obituaries (2010). I wanted more of this less elevated, gossipier stuff because Cooper’s middlebrow writing often echoes these “circuits of being-with” in more approachable terms. Alongside appreciations of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the World Wrestling Federation, Smothered in Hugs gathers conversations about post-Stonewall queer outsiderdom with Clive Barker and Bob Mould, as well as off-kilter interviews with rising hunks such as a twenty-five-year-old Keanu Reeves (in the pages of Interview, no less):

Cooper: I know these punks in Toronto who adore you so much that they invented a dance called ‘The Keanu Stomp’ based on the way you walked in Prince of Pennsylvania.Reeves: No!!!Cooper: Yeah. Apparently it’s turning into a bit of a fad. There are slam pits full of punks doing ‘The Keanu Stomp’ even as we speak. In fact, two of these punks, Bruce LaBruce and Candy, who head up this gay and lesbian anarchist group called the New Lavender Panthers, begged me to ask you some questions for them. Is that okay?Reeves: The New Lavender Panthers! Whoa!! Sure, it’s okay.

One of Hester’s stand-out chapters reads Cooper’s opposition to the “creeping conservatism of the gay movement” through his correspondence with filmmaker LaBruce, prolific queer zine publisher G.B. Jones, and the rest of Toronto’s Queercore scene, and Cooper’s public enthusiasm for their work indicates something beyond private agreements recorded in archival correspondence. In other words, Cooper’s interest in youth culture and the dynamics of identification amount to much more than a fun conversation with a famous hot guy.

Thinking of Cooper’s place in the literary canon, celebrity might also be a way of approaching the distinction between his writing and that of the Downtownies, the New York School poets, the New Narrative writers, and the other groups with whom he fits uncomfortably. These writers tend to deploy a charismatic inside-outside dynamic, whereby persons mentioned only by given names are either celebrities to the hip (“Jimmy” is the poet “James Schuyler,” say) or alluring passcodes to the out-of-orbit. In Cooper, however, the “inside” is filled out by damaged teenagers and the men who damage them, and if we imagine who would populate the outside looking in, we likely arrive at law enforcement, case workers, and predators, not aspirational friends. Hester offers a vibrant set of interiors, real and historically significant, but I wonder how much someone can be talked into Cooper’s literary worlds. They feature “insides” whom you are trapped within instead of comforted by, and “outsides” who are cruel and wholly in sway to whatever resources those predators can offer them to turn a blind eye. In this way, Cooper speaks powerfully—if obliquely—to our era of deep suffering and infuriating indifference from those who have the power to end that suffering. But because Cooper doesn’t expressly implicate capitalism, homophobia, or structural racism on those terms, he often misses out on an audience that deserves him.

This is, perhaps, another virtue of his poetry: it’s an excellent entry point to thinking with him about what society does to young people, and we are lucky to have Hester’s sustained, rich readings. Cooper’s poetry, and Wrong, may together change the minds of some who’ve been inclined to write him off.