This essay appears in print in Imagining Global Futures.

A powerful wave of protests in Iran has shown the world, again, the resilience of a people fighting against authoritarian government, economic inequality, and gendered violence.

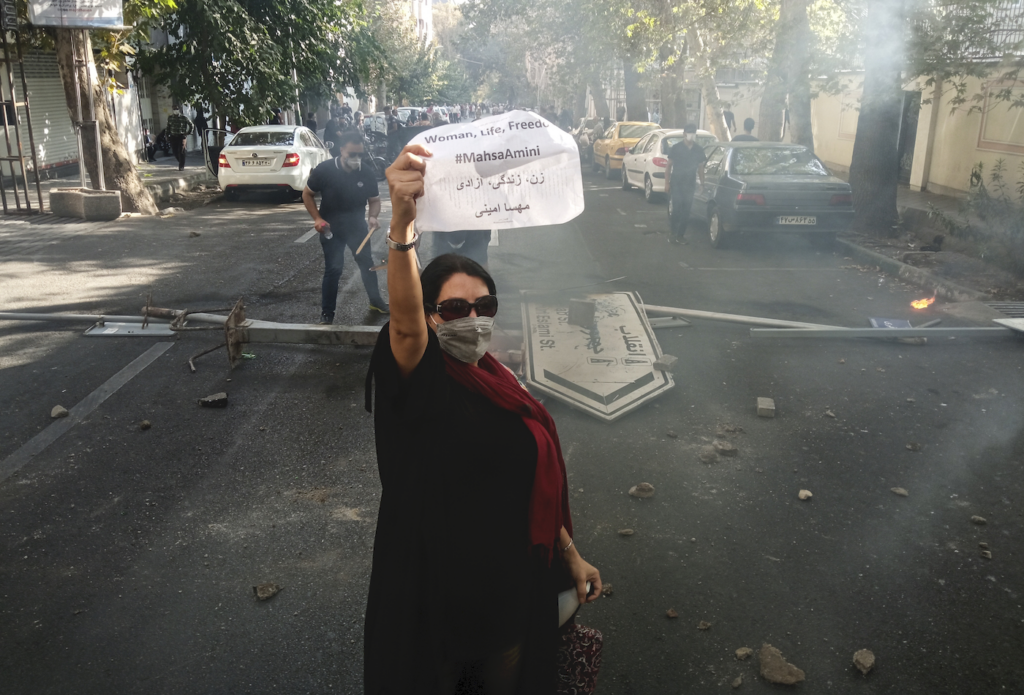

The uprisings have continued for over a month and grown to encompass student demonstrations and workers’ strikes, but women have been at the forefront of the movement since the beginning. Triggered by the killing of Mahsa (Jina) Amini at the hands of the Islamic Republic’s morality police (the gasht-e ershad, or “guidance patrol”) in September, the movement soon mobilized under the chant of zan, zendegi, azadi—“women, life, liberty”—and has used social media posts alongside street demonstrations to critique the government’s violent apparatuses of control over women’s bodies and life choices.

Observers outside Iran have alternately characterized these events as demands for the reform of legal norms or as revolutionary praxis that seeks to undermine the very foundations of the ruling clerical establishment. While it is too early to tell the outcome, the events of the past month constitute a historic moment in the Iranian people’s struggle for freedom from domination. Anyone committed to democracy has something to learn from the demands and creative forms of contention used by Iranian dissidents. Perhaps most notably, the protests include an explicit call for a cultural shift alongside demands for democratic institutions. In this, they exemplify an underappreciated form of democratic agency, spearheaded by Iranian women and other marginalized people in Iranian society on their own terms.

For some it may be tempting to narrate this moment as the inevitable triumph of Western liberal democratic norms over religious fundamentalism and stubborn authoritarianism. The reality of the Iranian people’s strivings is more nuanced. The concerted effort to expand the category of “the people” is not a call for regime change catalyzed by foreign governments or for the exportation of a particular brand of liberal democracy: it is an organic movement that continues to define its democratic ambitions through each act of resistance, each instance of imagining governance otherwise.

One of the remarkable facets of this resistance is the creativity through which protesters, led by women, make their voices heard and their demands known. Their actions—through song and dance, artistic interventions and performances—illustrate the multiplicity of forms through which democratic agency can be enacted and mobilized. Whether exhibited through the spectacle of protest or the quotidian pushback against rigid societal norms, these aesthetic forms make up the lifeblood of democracy in Iran. And this tradition on the part of marginalized Iranians has a long historical legacy. Their struggle against domination has been protracted, hard-fought, and multifarious.

The strivings of women in Iran to exercise greater autonomy over their self-expressions have not always played out through critique of a particular political regime like the Islamic Republic. Long before compulsory hijab was mandated in the year following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iranian women had been negotiating the politics of the veil as a form of control over their bodies. Every ruling group—from the Constitutionalists in the early twentieth century to the subsequent Pahlavi dynasty and most recently the Islamic Republic—has attempted to demarcate women’s bodies as contested terrain on which physical markers with symbolic meanings could be imposed. And while it is one of the most salient symbols, the veil is not the only form of representation that women in Iran have continued to challenge. The history of their manifold endeavors reveals a variety of expressions demanding control over life choices and the freedom of self-representation.

Iran undertook one of the most significant experiments with democracy at the turn of the last century with the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911. The constitutionalists who challenged and imposed limits on the ruling Qajar dynasty established a parliament that purported to represent the whole people, but like so many governments making such claims, it turned out to be highly exclusionary. Through a gendered concept of citizenship, women were deprived of voice and decision-making in government, all the while a new bill of rights professed to guarantee citizens legal equality and protection of life and property.

Denial of women’s autonomy continued through the Pahlavi dynasty—notably with Reza Shah’s forced unveiling of women in 1936—and in the ensuing decades, when laws were drafted to regulate their lives without their consent. Though they fought for and were granted voting rights under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1963, gender inequality remained persistent through the imposition of societal norms that prescribed particular roles for women: companions of men envisioned as the authoritative leaders of a modern Iran, or accessories to an increasingly masculinist project of modernity.

Yet none of this tells the full story of women’s role in fighting for a more meaningfully inclusive society. Faced with unjust political and legal mandates alongside oppressive social norms, Iranian women found creative ways to resist regulatory discourses through writing, speaking, and performing their agency in their own voices.

As early as the nineteenth century, Iranian women took up the pen in a bid to critique and reshape the culture. One of the most remarkable such figures was Bibi Khanum Astarabadi (1858/9–1921). Known simply as Bibi Khanum, she is remembered for writing one of the most scathing critiques of men’s comportment toward women in Qajar Iran before the constitutional period. As a response to a widely circulated and deeply sexist tract, The Education of Women (Ta’dib al-Nesvan), Bibi Khanum wrote her own Vices of Men (Ma‘ayeb al-rejal) in 1894, repudiating the claims of women’s subservient or inferior status. With incisive humour and wit, she dismantled each of the ten recommendations in The Education—including women’s obedience, forbearance, and “proper” bodily comportment—and further took men to task for their vices and hypocrisies. As she notes, she was encouraged by other women who felt The Education deserved a strong response. Vices of Men indicates the enduring presence of a powerful counter-discourse against dominant narratives in Iran’s public sphere.

Though many barriers to public expression persisted throughout the twentieth century, female writers and poets in Iran found ways to express themselves through the mediums most readily available to them. As literary scholars such as Farzaneh Milani have documented, women were long excluded from certain art forms such as music or painting but crafted a home for themselves in verses and narratives. Since fiction and poetry require little more than a pen and pad, these forms became accessible and conducive for women to articulate their experiences, desires, and critiques of society.

Two of the most significant figures in this tradition during and after the Pahlavi era included Forough Farrokhzad (1934–1967), and Simin Behbahani (1927–2014). Though perceived as transgressive and even scandalous in Iran, poems like Farrokhzad’s have made a forceful and persistent case for freedom: freedom from the captivity of unequal laws and social norms, and freedom to speak and write without the domination of top-down moral standards. The message in Farrokhzad’s work often reverberates through the powerful use of irony against those who would chastise her for living and writing as she did:

Forgive her.

Sometimes she forgets

she is painfully the same

as stagnant water,

hollow ditches,

foolishly imagines

she has the right to exist.

Likewise, Behbahani’s poems have become well-known emblems of defiance against political domination and strictures against freedom of expression. In one of her most powerful verses, Behbahani wrote herself into the project of creating a new Iran, against earlier iterations of the project of modernity:

My country, I will build you again, if need be, with bricks made

from my life. I will build columns to support your roof, if need be,

with my own bones. I will inhale again the perfume of flower

favored by your youth. I will wash again the blood off your body

with torrents of my tears.

Far from esoteric literary experiments, these verses have been woven into the fabric of social and political consciousness in Iran. They have endured for decades, and they go on being sung against oppression in its many forms.

The appeal and resilience of Iranian poetic discourses shouldn’t be surprising. Other narratives cherished in the Iranian imaginary stretch at least as far back as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in revered poets like Rumi and Hafez. Besides being read for pleasure and spiritual exploration, Sufi poets have always exuded a spirit of rebellion. Extolling intoxication and self-questioning as ways to better understanding truth and ethical comportment, they articulate a sense of agency that has long defied rigid norms imposed by authorities. They affirm self-care alongside an unwavering commitment to love as a socially bonding force across ideological divides, rethinking and rewriting what it means to be Islamic. And they have remained steadfast in their nonconforming ways of living, derided as shameful by the falsely pious but precious to those who understand and live by its principles.

A characteristic poem from Rumi espousing drunkenness and love captures some of the flavor of a poetic discourse that has scandalized ruling clerical authorities since its inception:

Let go of all your tricks, lover,

be possessed, madly in love

Lose yourself in the heart of the fire,

like a moth consumed in the flame

Lose yourself and bring down your home,

come live with other lovers, in a new home

Wash grudges from your breast with water from the Seven Seas,

then fill up with the wine of love, like a wine cup

You have to become a brimming spirit to be worthy of the beloved:

when you go among the drunkards, be drunk, beside yourself.

Hafez likewise occupies a central role in elaborating a discourse of poetic dissidence among Iranians, boldly taking aim at Islamic jurists:

Our preachers who make grand displays on their pulpits

act in a different way as soon as they’re in private.I have a dispute against these wise jurist leaders:

why do those who preach penitence so rarely practice it?You could say they have no belief in Judgment Day

the way they practice deceit and hypocrisy in God’s name.

Against these pretensions, Hafez extends the metaphor of wine-drinking to propose another way of living by a community of resisters:

I refuse to quit the love of the beloved, the love of wine.

I said a hundred times that I’d repent, but I won’t. . . .The preacher told me with reproach: “give up love!”

There’s no need to argue, my brother, because I won’t.

Rumi and Hafez are only two figures in a rich tradition of Persian poetry opposed to rigid understandings of Islam and political authority. Recent studies have offered illuminating accounts of how Iranian women use this poetry to contest gendered exclusions and inequalities on their own terms. They stand as fresh reminders of how poetry has weaved its way into the private and public life to sustain forms of democratic dissent rumbling below the surface of everyday life in Iran.

Iranians’ efforts to critique exclusionary political structures alongside unwritten ethical norms have also manifested themselves in both private and public spaces. Since the Islamic Revolution, the state’s regulation of bodies has prompted myriad forms of resistance by women demanding access to public sites while cultivating dissidence using the means and spaces available to them. Though the state has sought to continue its management of bodies through a subtle but persistent exercise of power, women have actively amplified their own power within homes and in the streets. This kind of pushback is central in a wider wave of resistance long present in post-revolutionary Iran.

Building up through the 1990s to the early 2000s, expressions of popular opposition to the government found a peak in the 2009 Green Movement, which saw a massive outpouring of public defiance in the streets. In its wake, analysis focused on the growth and resilience of civil society as a key indicator of democratic promise. The people—prominently women, oppressed religious minority groups, and the underrepresented working class—had announced their presence more forcefully than ever, it seemed, signaling a turning point for Iran. The regime responded brutally, killing, jailing, and silencing opposition figures. But as recent events show, the spirit of democratic agency and resistance has not been totally stifled.

In fact, these democratic practices endure even in the midst of severe repression because Iranians enact them persistently and fearlessly in their day-to-day lives. They write and recite the forms of freedom they long for. They breathe it each time they challenge oppressive norms within their homes. They perform democracy by marching, dancing, singing in the streets. All of this is done to change the culture, so that their own vision of democracy can continue to take root. And as the latest protests reveal, it is this site of culture that can provide insights about the prospects of an organic democratic growth in Iran—as well as lessons on the meaning of democracy writ large.

What exactly can those living under an authoritarian regime in Iran show “Western” observers about ways to rethink the practice of democracy?

Democratic theorists in Europe and North America tend to focus heavily on a certain Western understanding of democracy: one that has its historical roots in Judeo-Christian, Greco-Roman, and modern European canons of political thought and its contemporary tribulations in liberal societies characterized by diversity and polarization. Within these contours, prominent arguments about ways to strengthen democracy range from the expansion of democratic inclusion, which aims to amplify empowerment and voice, to the imperative of justification, through which agents give reasons to one another to build or reconstruct norms where they are found non-justifiable. Extensions of Jürgen Habermas’s discourse theory emphasize deliberation among free and equal participants who contribute to the making of legal norms and collective decision-making as crucial to the vitality of democracy.

While numerous variations of (and challenges to) these approaches are widespread in the discipline, the study of democratic theory still remains heavily grounded in the Western experience, leaving the struggles and contributions of those outside of the West in the periphery. This tradition of political philosophy has its place, but we would do well to try to expand our field of vision and consider other experiences for richer insights about ways to practice freedom and democracy.

To this end, a burgeoning literature is drawing our attention to the way political theory can and should be envisioned as a wider global endeavor, with special attention to understudied historical and contemporary resources for normative and democratic theory. Scholars attuned to anticolonial perspectives have also called for a productive rereading of such figures as Mahatma Gandhi and Frantz Fanon as thinkers who can help us to reimagine the study of politics. The revolutionary Iranian thinker Ali Shari’ati has likewise recently been the subject of significant interventions that reconstruct an understanding of social transformation with emphasis on self-fashioning through the pursuit of collective freedom and mutual learning. The particularities of politics in Iran in recent decades—its embattled attempts to reinvent freedom and democracy—make it fertile ground for political analysis.

In addition to the important literature that takes an explicitly political focus to understand struggles like that of Iran, attention to the wider sphere of culture can be useful for perceiving democracy in action—even when efforts within that sphere aren’t nominally labeled democratic by the agents who carry them out. This kind of study can also add to insights in Western democratic theory, which has had a lot to say about conceptions of autonomy like Kant’s but much less about manifestations of democratic agency in struggles against oppression and injustice outside of the West. In this other view, democracy is born out of and maintained through resistance. And much of this resistance, as we continue to witness in Iran, takes place in the realm of culture: sung softly within homes and loudly in the streets, performed through dance and creative protests, and visualized in the art spontaneously appearing across Iran’s landscape daily as a reminder of what democracy looks like.

The cultural shift propelled by Iranians, with women at the helm, has been prefigured through countless smaller permutations and acts. In a telling and beautifully written account, an anonymous protester in Iran known simply as L described the ongoing uprising as the “figuring” of a women’s revolution: the enactment of resistance through the spontaneous yet intuitively premeditated positioning of bodies to create lasting images in the minds of other participants and observers. In the aftermath of Mahsa Amini’s murder, women took to the streets not only to march and chant but to situate themselves physically in public spaces as an act of reclamation. They stood on cars, concrete barriers or any platform that would give them visual prominence and defiantly held up their removed headscarves as symbolic gestures of resistance. From Tehran to Bandar Abbas, they danced around fires in the street, at times whirling in a way reminiscent of the dissident Sufi tradition. These acts are both impromptu and deliberate, long in the making through myriad narratives and images of intransigence.

Iran’s culture has also been a fertile ground for resources of democratic resistance and self-questioning about issues like gender inequality. In the realm of film, Abbas Kiarostami’s insistence on putting women’s faces front and center exhibits a form of radical artful experimentation. Currently imprisoned director Jafar Panahi has brought the plight of Iranian women to light in films such as The Circle (Dayere) and Offside, and Samira Makhmalbaf has explored education and women’s rights in At Five in the Afternoon. These are just a few works among many that have garnered both international attention and dialogue at the domestic level: they have helped impel an ongoing conversation about what kind of society Iranians want for themselves.

Music is another significant medium of political critique in Iran. The subtly subversive work of the late Mohammad Reza Shajarian has been carried on by his son Homayoun Shajarian, who through performances in Australia paid tribute to Mahsa Amini in the days following her killing. Shajarian, among other well-known Iranian public figures, recently faced reprisal, having his passport temporarily seized upon returning to Iran. The republic’s censors are aware of music’s powerful effects and potential for destabilization of the regime; bans on taboo subjects and solo performances by female singers have been in effect since its founding in 1979. But this has not stopped other figures like Mohsen Namjoo and the rapper Hichkas—among many underground performers documented as defiant voices—from ongoing critique of the regime and its attempts to instil control and obedience. It is also unsurprising how a musical performance by Shervin Hajipour—pieced together from online expressions of solidarity and dedicated to women and all those fighting for freedom in Iran—became one of the main rallying cries of the present movement.

There is perhaps no stronger indicator of resistance in contemporary Iran than symbolic and visual representations. Iranians have been inventive and adept at using the power of images through art and performance. Their long-standing enactments are especially revealing as to why the current movement remains so forceful and resilient. Though it has only more recently gained greater prominence, art has been thriving underground in Iran, both spatially and symbolically. Censored artists have resorted to using spaces ranging from abandoned buildings in Tehran to rural areas and desert landscapes for spontaneous creations of visual art and dramatic performance. Others have worked within the limits imposed on them by the regime, at times playfully reappropriating its imagery and symbols to signal disobedience.

Ultimately, the daily actions of Iranians, with all their creative forms of protest and artistic intervention in the past month, speak most loudly about the kind of democratic resistance they want to uphold. Images of lifted hands and fountains marked by blood serve as memorable testaments to the brutality of the regime and an unwillingness to forget the violence it has visited on the Iranian people. Photos of schoolgirls spurning the founders of the Islamic Republic and reaffirming the slogan zan, zendegi, azadi linger in the memory and keep the principles of the movement from slipping into ephemerality. Coordinated recitals repeat the will of the Iranian populace to reclaim their homeland from a regime that refuses to represent their needs and interests. All of this, in a nation where democracy has yet to be secured and institutionalized, is democracy expressed not simply as a desire but as already in the grasp of the people performing it each day.

In this vital moment of democratic resistance, the Iranian people themselves are defining the changes they want to through their own actions, on their own terms. Whatever change is to come politically will inevitably be driven by the bravery, resourcefulness, and creativity of the people who practice democracy each day in cities and towns across the country. Whether those of us outside Iran are invested in the possibilities of its democratic future or simply interested in the applications of democratic theory in practice, we would do well to heed the actions of ordinary Iranians pushing back against their government to transform their culture. Their hard-fought and ongoing efforts demand that we all take note of the cultural outgrowths they have been cultivating and appreciate their struggle.