Selected Poems

Thom Gunn, edited by August Kleinzahler

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $14.00 (paper)

At the Barriers: On the Poetry of Thom Gunn

edited by Joshua Weiner

University of Chicago Press, $25.00 (paper)

Thom Gunn’s 1957 book The Sense of Movement was published in a relatively tame era. He had not yet begun to deal openly with gayness, sex, and hallucinogenic drugs. Still, amid the poems is one called “St. Martin and the Beggar,” which forecasts a little of what is to come. The poem retells, in jaunty, Audenesque sestains, the legend of the fourth-century soldier from Amiens who halved his cloak to clothe a passing beggar in a storm. Martin rides on, slightly disrobed, getting wet. At the inn he is rewarded with a vision of the beggar, who appears, in Gunn’s telling,

Now dry for hair and flesh had been

By warm airs fanned,

Still bare but round each muscled thigh

A single golden band,

His eyes now wild with love, he held

The half cloak in his hand.

It turns out that the beggar, now clothed in sexy, thigh-gripping bands, is actually a Christ figure who wants to reward St. Martin, not just for giving him his cloak, but also for only giving him half. “You recognized the human need / Included yours,” says Gunn’s version of the beggar-turned-Christ:

‘My enemies would have turned away,

My holy toadies would

Have given all the cloak and frozen,

Conscious that they were good.

But you, being a saint of men,

Gave only what you could.’

All of this raises some fascinating questions. What can we give? What do we owe to the body, our own or someone else’s? What do we owe to the stranger? And is the body itself a stranger whose needs are not our own?

Though Gunn was an avowed atheist who would later vary his early commitment to traditional meter and rhyme, “St. Martin and the Beggar” makes a fine introduction to his concerns. It opens with a partly clothed encounter with a stranger (if not from San Francisco’s Market Street, then at least from another foggy moor) and jumps off from this revelation (apparition?) to explore, explain, and celebrate the needs of the speaker’s—and, by extension, everyone else’s—physical, living body. To have a beggar turn into Christ is common enough, but to make him a quasi-Christ, hot and muscle-bound, freshly blow-dried, wearing golden thigh bands, his eyes “wild with love” for your corporeal, sensual self—and then to celebrate your sensual body as ethical, necessary, and therefore perhaps even saintly—well, that’s Thom Gunn.

Gunn made a lot of moves that only Gunn could make, though his poetics also recall Whitman’s gloriously expansive declaration: “Do I contradict myself? / Very well, then, I contradict myself; / (I am large—I contain multitudes.)” Gunn’s multitudes could be found not only in the multiplicity of bodies he attended to, including his own, but also his willingness to align seemingly contradictory aesthetic forces in the service of an art that is both inclusive and transcendent.

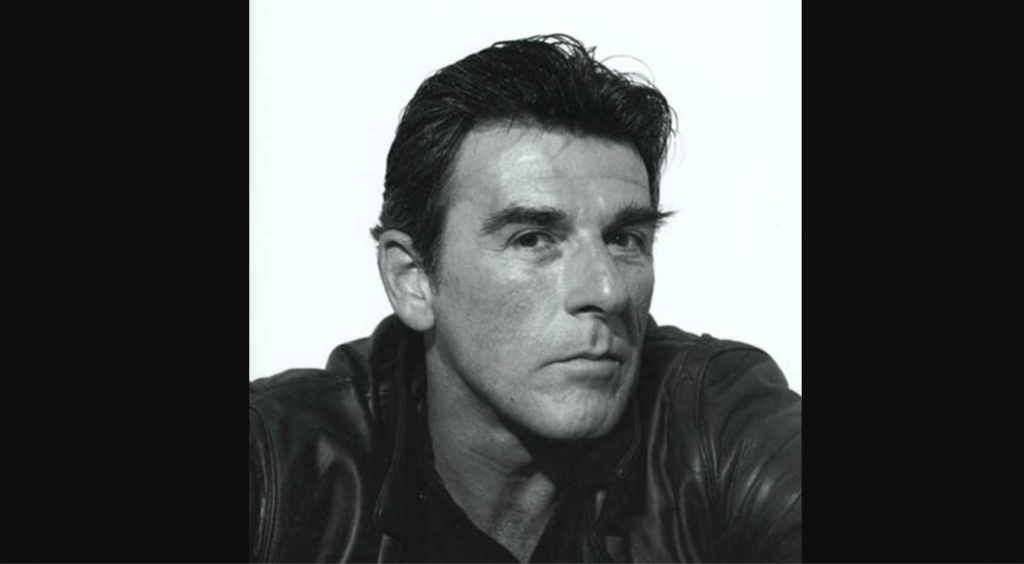

Gunn, who would have been 80 last year, is now the subject of two tributes that celebrate his poetics and the multiple blessings he and his half-cloak continue to bestow on poetic communities—not that he would likely have accepted even the suggestion of something as restrictive or dogmatic or just plain prissy-sounding as “a poetics.”

At the Barriers: On the Poetry of Thom Gunn, edited by Joshua Weiner, includes essays by Weiner, August Kleinzahler, Robert Pinsky, Wendy Lesser, and others. A tightly pared Selected Poems, edited by Kleinzahler, makes Gunn’s work newly portable even as it stages a critical reevaluation of that work as a whole. To read the books together is to see how Gunn is a figure in whom people find what they need. That’s okay: Gunn pitches a wide tent, and his models and literary fusions are especially enabling. Gunn himself was suspicious of easy formulations (aesthetic or otherwise), and he was leery of critics, criticizing, and criticism. In his contribution to At the Barriers, Brian Teare quotes an especially revealing passage that Gunn wrote in the 1960s, stating that he had become “more and more dissatisfied with the business of making comparatively fast judgments on contemporary poets.” “I felt,” Gunn went on, “more and more that I had to live with a book for some time before I could really find out its value for me.”

Kinetic, mnemonic, sensual poetry, alive to the body; mind-altering drugs as a way of reading the mind within both world and body: Thom Gunn was just plain sexy.

Gunn was after answers—and fusions—that served him, but he was equally reticent about limiting or over-defining who the self he was serving was. Ducking critical establishments, he used the space this avoidance created to become the kind of poet he needed to be—one who, despite my reference to Whitmanian inclusiveness, saw his life’s work explicitly not as contradiction, but as continuum. Gunn’s life and poetic practice both traveled and fused divergent traditions: a British upbringing that shuttled back and forth between more wealth and leaner times; his immersion in postwar British Modernism; a Cambridge education immediately following which he published a book that was evaluated beside the work of Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin; a move to California in the ’50s to study with Yvor Winters; his late immersion in American Modernism; his emerging willingness to out himself; his more countercultural friendship with the poet Robert Duncan; his experiments with open sexual relationships and with drugs; his witness of the AIDS crisis. All these he folded into his poems, not so much resolving any tensions as allowing coexistence, juxtaposing facets in tension across 50 years of work. Sex, drugs, rock-and-roll, formal verse with the elegance of a latter-day Ben Jonson; kinetic, mnemonic, sensual poetry, alive to the body, embracing the world; mind-altering drugs as a way of reading the mind within both world and body: like his muscle-thighed visitor, Gunn was just plain sexy.

Later in Gunn’s career, the revelation the speaker experiences in “St. Martin and the Beggar” might not have come from a Christ, and the poem itself is absent from Kleinzahler’s selection. Such a vision would more likely have been fueled by drugs, a late-night sex party, or the joined bodies of people swimming naked in a Northern California geyser. It might also have been sparked by the experience of getting into bed with a longtime partner. Revelation becomes, in a word, more experiential than imagined. Here is the half-cloak—that sign of what, as humans, we both need and share—refigured as a whole blanket in the poem “Touch,” in which the speaker, “numb with . . . the patina of self,” climbs into bed with a body, a presumably known but also anonymous “you,” who is also figured as numb, a “mound of bedclothes” next to the cat. The warm “you” breaks down the chill, even as

You turn and

hold me tightly, do

you know who

I am or am I

your mother or

the nearest human being to

hold on to in a

dreamed pogrom.

Nightmare companion as closest intimate? No matter. The speaker sinks into what he calls “an old / big” place that is “hard to locate”:

What is more, the place is

not found but seeps

from our touch in

continuous creation, dark

enclosing cocoon round

ourselves alone, dark

wide realm where we

walk with everyone.

The half-cloak, the gift that recognizes universal human need, is refigured as touch, a blanket and cocoon, an enclosure created by the communion of the self and an other. We have to touch and be touched to feel the physical reality of our bodies, though in being touched we loosen our grip on, and even lose hold of, something as small and petty as ourselves: we weave the cocoon of touch to dislodge the patina of self. This is one of Gunn’s persistent paradoxes. As a poet he also patterns and captures these pleasures in language. In Gunn’s poems, physical pleasure (including sonic, rhythmic, linguistic pleasure) is both the blanket we give and the one blanket on which we lose ourselves.

As well as “Touch” encapsulates Gunn in the 1960s, it also projects the direction his work would take in the following decade with Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), only scantly represented in this Selected Poems. Gone is Gunn at “The Geysers” of Sonoma, California, where he is camping with quite a lot of people, none of whom are wearing very many—or even any—cloaks at all. The “starlit scalps” of the hills are “parched blond” (anyone who knows these hills will see how lovely a characterization this is), and where it is wet there is “dark grass fine as hair.” Everyone is sleeping “in the valley’s crotch.” The willingness to regard the landscape as an anonymous lover and the waking self as a half-stranger is enchanting.

There is good reason to point out this expansiveness now, and to revel in how liberating a vision of poetic making it offers. In his introduction, Kleinzahler notes a tendency, especially among older critics, to see Gunn’s earliest work (also the most formal and arguably the most closeted) as his “best,” with his later depictions of sex and drugs and his use of American Modernist forms as a fall from grace. In the mid-1980s, Scottish critic Kenneth McLeish wrote blearily that “Gunn is living proof of that sad cliché that first thoughts are always the best,” going on to say that Gunn had been steadily in decline since his early bravura. Kleinzahler will have none of it. He also wants to challenge the notion that the Gunn who came back to popular consciousness—the Gunn of the AIDS crisis, who reemerged in 1992 with The Man With Night Sweats—was markedly better or more feeling. No, Kleinzahler says, Gunn was revolutionary, again and again, all along.

Gunn recognized addition rather than rupture. His experiments in life and poetic form were an extension toward rather than a divorce from the past.

This might be argument enough for a new selection of Gunn’s poems, in which forays into drugs and all-night parties no longer shock, and no longer distract. Thus it has become much easier to see the tense rhetoric of Fighting Terms (1954) not as an early apogee, but rather as something that deepens dramatically into the LSD-induced Moly (1971) and beyond. Gunn was still a Brit, to be sure, and in At the Barriers Paul Muldoon makes some apt connections between Gunn and Hughes, showing Gunn remaking Hughes’s iconic “The Thought-Fox” in a tattoo parlor. But Kleinzahler wants to reframe a school of critics whose measure of value narrowly favored early work while neglecting the middle years; he wants to follow Gunn through bathhouses and sex clubs and other places of liberated possibility, on to the formal, Jonsonian portraits of AIDS, of his mother’s suicide, to the end, to the years when Gunn answered to, and wrote for, Boss Cupid (2000).

But despite his willingness to take Gunn whole, Kleinzahler’s edition feels slim. He praises Gunn’s “Baudelairian sensibility,” but leaves out many poems that capture pungent Tenderloin street life, Gunn’s Dickensian San Francisco. Oddly enough, Kleinzahler, who can be pretty raunchy himself, tames Gunn down. He certainly offers a newcomer the chance to stop in with Gunn for breakfast, lunch, or a 3 a.m. drink, but he also forces the reader to turn back to the 1994 Collected Poems. The older volume allows us to watch, in a way that this Selected Poems does not, how Gunn’s explorations of radical freedom fold back on the problems of expressing those explorations. As Gunn asks in “The Value of Gold”—absent from Kleinzahler’s edition—“Can this quiet growth / Comprise at once the still-to-grow / And a full form without a lack? / And, if so, can I too be both?” And later, in the long poem “Misanthropos,” also omitted, he writes: “Bare within limits. The trick / is to stay free within them. / The path branches, branches still, / returning to itself, like / a discovering system, / a process made visible.” Which is precisely how Gunn worked: his poetry, like his life, was a discovering system.

Some critics find it tempting to plot Gunn’s career across several spectra of understanding, motions from canonic England to counterculture California, from the closeted 1950s to AIDS and beyond, from traditional to open forms, as though each of these shifts were somehow cognates, representative of one another. But while these spectra exist in Gunn, they exist only as spectra, as imaginative occasions for understanding, rather than as points in a narrative. This is not the story of a man who wrote in form and then moved to California in order to come out of the sexual and compositional closet. The story is not so linear, and it wouldn’t be Gunn’s narrative if it couldn’t be somewhat dislodged from anything so pat. Gunn’s work across time is aware of categories, but while it celebrates camping, it dislikes camps.

Indeed, both newcomers and inveterate Gunn enthusiasts can be guided by Weiner’s delightfully rangy gathering of essays. Eavan Boland celebrates Gunn as an “island maverick . . . deeply nourished by tradition and lovingly open to change.” Neil Powell explores the Gunn of disguise and impersonality, for whom poetry—a record of and figure for the sensory body—is an elaborate costume (or even a cloak!) through which to arrive at truth separate from the self. Clive Wilmer examines Gunn’s debts to the Elizabethans in forging a dramatic persona that allowed him to sidestep the pitfalls of confessionalism and to navigate the architecture of hidden and revealed identity. And Keith Tuma’s “Thom Gunn and Anglo-American Modernism” describes how Gunn, facing vastly divergent American and British traditions, deliberately tried to work through “the barriers” between them. Weiner’s essays actually enact the critical re-evaluation that Kleinzahler has proposed. While Kleinzahler’s companionable Selected Poems sets the groundwork for seeing Gunn anew, Weiner’s collection actively recognizes the fullness of Gunn’s multiplicity—and his aesthetic continuum.

As a poet, Gunn recognized addition rather than rupture: his experiments in life and poetic form were an extension toward rather than a divorce from the past. Throughout his working years, Gunn also fostered what Weiner calls a “premodernist conception of poetry’s cultural role.” In Gunn’s own words, what a poet has to learn is that

he has inherited a genre onto which it is still possible for the whole of experience to bear: the body of his work should not be a collection of phenomena or of beautiful things, but should add up to a comment on existence just as much as the body of a novelist’s work.

The existence that Gunn comes back to so often, which he argues for and within, is that of the body, the impersonal body, the sexual body, the naked body, the sleeping body, the waking body, the vagrant body, and ultimately the “body of work”: the embodied self, the live, multiply contradictory self, the unknown self from which the half-cloak of the poem springs.