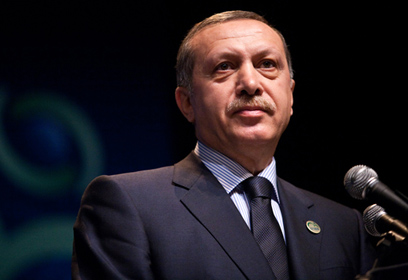

When I first visited Celil Sağır in December 2014, hundreds of protesters and police were arrayed outside his Istanbul office. They had come for his boss, Ekrem Dumanlı, editor of one of the largest daily newspapers in Turkey, Zaman. The government accused Dumanlı of supporting Fethullah Gülen, the exiled seventy-four-year-old cleric and rival of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), who has lived in Pennsylvania since fleeing charges of trying to topple the state in 1999.

Not too long before, Sağır, the paper’s managing editor, had been an ally of the AKP. Like “many other people from different ideological, religious, and ethnic backgrounds,” Sağır said, his “media group supported [the] AKP government against [the] Kemalist establishment in the fight to make Turkey a real democracy, a member of the EU.” He was close to Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu. “I flew around with Davutoğlu, and we would talk,” he told me.

But in the months leading up to that December, Sağır had grown concerned about the AKP agenda he had once backed. He warned me Erdoğan’s campaign against Gülen’s supposed “parallel state,” then in its early stages, would not be limited to Dumanlı and Zaman but would eventually ensnare all AKP critics.

‘It’s not a war between Erdoğan and [the] Gülen movement. It is a question of whether or not Turkey will be a real democracy.’

Sağır’s intuition was well founded. In the past year, hundreds of Turkish journalists have been prosecuted or threatened with criminal charges. Though their reporting has never been disproved, and their destabilizing motives never established, some have been charged with espionage or attempting to overthrow the state. As the nation confronts a wave of bombings—from Ankara last October to Istanbul and Cinar last week—journalists and government officials have been accused of terrorist activity. Others have faced lesser allegations for, in essence, offending Turkey’s leadership. More than a thousands scholars who spoke out against civilian casualties resulting from military operations against Kurdish separatists are now under investigation from state prosecutors and their own universities.

When we met again in December of last year, Sağır—a bearded, religious man—had just returned from a protest against the detention of Can Dündar, editor of the secular newspaper Cumhuriyet. Dündar had run a story revealing that the government’s intelligence agency (MIT) was supplying weapons to Islamist rebels in Syria, possibly even to the Islamic State and Jabhat al Nusra. Cumhuriyet’s front page carried pictures of investigators rummaging through mortar shells and thousands of rounds of ammunition. Soon after the story broke, Erdoğan appeared on state-owned television suggesting that the paper had acquired its evidence through the Gülen movement. He vowed that the editor would “pay a heavy price.” Dündar, now charged with spying, faces life imprisonment if found guilty.

For all his AKP bona fides, even Sağır is not immune. Along with two colleagues at Zaman, he has been handed a suspended sentence of more than a year for insulting the president and prime minister. On three occasions, Sağır’s Twitter accounts have been suspended, and Sevgi Akarçeşme, editor in chief of Zaman’s English-language edition, was found guilty of insulting Turkey’s leaders for tweeting, “Davutoğlu, the prime minister of the government that covered up the corruption investigation, has eliminated press freedom in Turkey.” Akarçeşme was even held liable for a reply by another Twitter user calling the prime minister a “big liar, puppet of the palace, scumbag.”

On January 6, Gülen himself was placed on trial—in absentia—along with dozens of former police officers loyal to him, charged with attempting to overthrow the government. “It’s not a war between Erdoğan and [the] Gülen movement,” Sağır told me. “It is a question of whether or not Turkey will be a real democracy.”

Once, it was democracy that brought Gülen and Erdoğan together. The two religious men wanted to change the Turkish Republic through the ballot box, and, in 2002, they did just that.

For most of its history, the state had not been kind to practicing Muslims. In school, children learned one version of the country’s history, and in mosques and cafés, the pious learned another: the nation’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, they said, hanged thousands of Islamic clerics and robbed Muslims of their culture, imposing on them a secular way of life. From Ataturk’s time onward, “White Turks,” the wealthy secular elite and its army, would run the country.

Gülen wanted to practice Islam his own way, inspired by Said Nursî, a Kurdish military commander who fought, like Ataturk, to create a Turkish state. But Nursî later turned against Ataturk’s secular project. A passionate exponent of Nursî’s views, Gülen helped attract millions of educated, conservative Muslims from the countryside to sometimes-underground study circles, where they pored over the Kurdish leader’s arguments against atheism.

Gülen’s movement, Hizmet, didn’t seek to confront the secular state. Instead of fighting the White Turks, Hizmet wanted to replace them. The movement thus founded some 4,000 tutoring centers, which prepared 1.2 million students for the exams they would need to pass in order to enter the police and judiciary. Many Hizmet members formed their own news outlets, opening papers such as Zaman, to counter a traditionally secular media landscape.

That strategy paid off in 2002, as the AKP won a historic election with widespread support. Hizmet backed the AKP directly, and its influence—through thousands of schools and some of the country’s biggest banks, TV stations, newspapers, and trade associations—was felt in the party’s appeal across ethnic and political lines. The AKP captured not only religious conservatives but also leftists, secularists fed up with the previous government’s illiberal methods, and Kurdish and Alevi minority groups. The AKP proceeded to make sure the military never staged another coup on behalf of the once-dominant right-wing nationalist Kemalism. “Generals were jailed, even top ones,” Sağır recalled.

According to Gareth Jenkins, an Istanbul-based researcher with the Silk Road Studies Program, Hizmet was essential to the purging of the military and other presumed or potential enemies of the new government. The AKP relied on Gülen’s extensive network of media outlets, prosecutors, and judges to expose opponents in the armed forces and bring cases against them. Even after the trials, thousands of phones were tapped, including, Jenkins said, his own. “It was very clear [that] members of the Gülen network sometimes manufactured and planted evidence and used their media to put out embarrassing material to the public,” he told me.

But the AKP-Gülen alliance didn’t last. Confident that it had most of the population’s support, the AKP at once set about realizing its dream of political Islam. Gülen, meanwhile, advocated smaller, more incremental reforms—hesitation that AKP supporters construed as betrayal.

Truthful reporting about government activities is increasingly criminalized.

One area of discord was the always-contentious place of the headscarf, which, under secular rule, had been banned in schools. After the AKP came to power, religious Muslims campaigned to eliminate the restriction, but female Gülen followers opted to remove the headscarf in schools rather than challenge the law. The government eventually rolled back the ban.

Another source of friction came in 2010, when an Israeli raid on the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish ship carrying aid to the Gaza Strip, killed nine people. While Erdoğan condemned the Israeli action, Gülen and affiliated journalists, such as those at Zaman, argued that allowing the Mavi Marmara to sail was bound to spark a confrontation.

The enmity between the two groups mounted further in 2011, when electronic bugs, apparently planted by Gülen’s supporters, were discovered in the offices of Erdoğan and other AKP leaders. The next year, police allegedly following Gülen’s orders sought to question the head of MIT over his agents’ purported infiltration of Kurdish groups engaged in peace talks with Turkey. Even today, the two sides disagree over those incidents.

In June 2013 the conflict came to a head. When police killed three protesters critical of the AKP and arrested thousands more during sit-ins at Istanbul’s Gezi Park and elsewhere in the country, Gülen issued a statement of support for the demonstrators and berated the ruling party for the crackdown. To bolster Gülen’s view, Zaman and likeminded papers covered the police response extensively, which irked AKP supporters such as Zeynep Jane Louise Kandur, a member of the party’s Women’s Branch and of its Foreign Affairs Department. “They made it sound like Turkey was on fire,” she said. “I thought these people shared our values and our concerns, and now they were producing hyperbole.”

Erdoğan hit back, threatening to use the AKP’s parliamentary majority to push through a law that would close Gülen’s tutoring centers. Later that year, Gülen-affiliated media released voice recordings of Erdoğan, his family, and senior AKP leaders indicating that some were taking bribes for government contracts. Three cabinet members implicated in the scandal were forced to resign, but the AKP blamed the allegations on Gülen followers who headed the investigation, many of whom were later removed. Gülen’s current trial stems from that episode. Along with fellow defendants, the elder cleric is accused of membership in a terrorist organization that sought to bring down the government through the corruption allegations.

Amid the back-and-forth accusations, opinions in the two camps have hardened. When the Gülen students chose not to contest the headscarf ban, Şura Durmuş, a law student and member of the AKP’s youth branch who studied at Gülen tutoring centers, thought her classmates were following their own spiritual convictions. But now that decision looks to her like part of a long-term plan for infiltration. “They hide their identities to become judges, lawyers, to join the military,” she said. “Now they have a huge network, in the judiciary, police, media. Someone decides [to prosecute], another arrests, and another publishes the news.”

“Some of the Gülen sympathizers who have been charged have engaged in criminal activity,” Jenkins said of the recent prosecutions of Gülen supporters. “But I think a lot of those who are being targeted are innocent both legally and morally. They are being prosecuted because they follow Gülen rather than because they have done anything wrong.”

Sağır agreed. “Hizmet includes millions of people, many qualified” to serve in the government, he said. “They might be sympathetic to [the] Hizmet movement, as many bureaucrats are sympathetic to different civil or religious movements or political parties. Is it a crime as long as they act in accordance with laws and regulations?”

Yet this is precisely the challenge that many officials and journalists now face. Those sympathies—not to mention truthful reporting about government activities and AKP-driven legislation—are increasingly criminalized.

“Because the AKP has gotten away with so much, it is now targeting papers like Cumhuriyet, along with the Gülen network,” Jenkins said. He offered the example of the Ankara Organized Crime Bureau, in charge of tracking intelligence related to terrorist groups, which he says was systematically re-staffed because of alleged Gülen sympathies. “Everyone was purged, including the tea maker and the dog,” Jenkins told me.

Even Durmuş, who recognizes that the Gülen movement is peaceful, nonetheless argues that Dündar and others exposing government activities are pouring gasoline on a fire. “Turkey is fighting two terrorist organizations now—ISIS and the PKK,” she said, referring, in the later case, to the Kurdish Workers’ Party, which seeks Kurdish independence from Turkey. “Of course Hizmet is not like these two [groups]; they are not laying bombs, or killing people. But they are trying to overthrow the government,” she said. “If a journalist publishes news about national security now—they know the law, they should face it.”

On the whole, Turks may agree with Durmuş: the AKP was reelected to a resounding majority in November. “Erdoğan got everything he wanted,” Sağır said. “And now maybe he sees Hizmet as his last obstacle.”

Sağır finds the conflict with Gülen ironic, given that Erdoğan himself rose to popularity after he was jailed in 1997 for reciting a poem that secularist authorities said was aimed at toppling the government. “Now he is doing the same to Hizmet,” Sağır said. It is “unfair and un-Islamic to call Hizmet a terrorist organization. . . . And, you know, it hurts to see this being done by people who call themselves Muslims.”