My obsession with the female face and narratives of its defacement has led me down a forking path of overlapping discourses, iconic images, and source texts, from Greco-Roman art to Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face, a memoir of living with Ewing’s sarcoma: after losing half her jaw, Grealy spent two and a half years undergoing chemotherapy and radiation, followed by twenty years of plastic surgeries. My inquiries are connected with my understanding of the media state’s supplanting of physical interaction with what Donald Bartheleme calls modernity’s “pneumaticity of the surface,” a virtual reality wherein we interact not with faces but screens. Even after the Lacanian mirror shatters, the screen remains; in this plasticity of seeing, the vulnerable, all-too-human face is experienced as yet another categorical box, and volume and depth—key tropes of Renaissance art—are evacuated.

The emotional core of this inquiry into the face and its tropes concerns my mother’s facial paralysis from a brain tumor operation. In witnessing my mother’s struggle, her loss not only of hearing but of short term memory and motor function through several operations, and in deeply identifying with her pain and self-consciousness from the time I was a child, I realized I communicated with my mother from a place not only of love and healthy attachment, but one shaded, since her diagnosis, with grief, fear, and psychosomatic mirroring. Mimesis is not just a pedagogical topos, but a form of situated learning, as well as survival. As I began sublimating these feelings and ideas in art and theory, I began to gain understanding, acceptance, improved visual literacy, and knowledge (or memory) of a somatic language constructed of affects.

Quests to connect the politics of reading to visual and spectacle culture are perpetual, as are attempts to discover another’s face, or one’s own face in a mirror, not as a projection or degree of semblance to kin, but as a distinct entity or individual. Modernism has turned iteration and recognition, in literature and life, into reproducibility and branding: if you have a unique style or concept, off to the advertising factory/copy machine/assembly line, to monetize the putative “real.” Given the ubiquity of the air-brushed face and the fear, especially for women, of aging or being considered useless apart from looks (“just another pretty face”), what, then, to make of faces carved into the Western historical imaginary—Helen’s visage catalyzing the Trojan War, Mater Dolorosa, Francis Bacon’s Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile—faces remembered not for iconic “beauty” but the manifest range of human expression, in extremis?

The face, in its nudity and defenselessness, signifies “Do not kill me.”

Perhaps more to the point today, how is reading an image—the “closed” or “open” book of the face—different from reading a text? How is privileging image over text a war against interpretation in anthropology, cinema, and literature? The media’s disavowal of the angry, aged, or simply uncosmeticized female face (“Stars Without Makeup” in People magazine are presented as social pariahs; celebrities posting casual selfies on Twitter are lauded for their bravery) can be read as terror of the proliferation of the actual. The codification of female types as dictated by Hollywood, pulp fiction, and online profiles (bookish; sluttish; housewifely; careerist) renders non-normative sexualities, queerings, and female desire unprofitable.

In a New York Times review of Thrown, Kerry Howley’s experimental non-fiction book about martial art fighters, Katherine Dunn’s description of the narrator character Kit speaks to this zeitgeist: “In all her highbrow singularity, Kit is the archetypal sports fan. She could well be the audience for all art. She is a vampire voyeur, the parasitic watcher, feeding on the bone-crunching efforts of the doers. She claims that the relationship is symbiotic, that the fighters need her as much as she needs them. And she’s right.” Dunn calls the book “a ferocious dissection of the essence of the spectator,” grounding learned passivity in a biological metaphor, and reading participation in rites of passage, culture, and juridical proceedings as a form of identity formation, value production, and self-actualization.

How, then, does the female face signify in contemporary spectacle culture, especially now that consumer culture (the diet and fitness industries in particular) preys increasingly upon men, straight and gay alike, as a group that is another cosmeticized money-maker? What to make of the transition, in the representation of women, from icon to seeker (Mary Magdalene with a Smoking Flame by Georges de la Tour) to enigma (Mona Lisa, Girl with a Pearl Earring) to prostitute to Cubist grotesque to porn star?

The following essays contain possible answers presented as scattershot from a detonation; an archipelago of cultural meanings and artifacts collected in the aftermath of the destruction of the organic body; evidence of the reduction of the animating subject to a fetish, hung on a wall, purposed for literal consumption, in a butcher’s shop, and viewing, in digital aesthetics, on a pixelated screen.

Meet your meat, indeed.

Woman Reading a Letter, Johannes Vermeer, 1663–1664. Image: Wikimedia commons

1. Faceless

If the face is the force that humanizes transcendence, what does it mean, exactly, to be faceless? Masks are worn for entertainment and tribal rituals, serving social functions from manifesting duende, to performing a second self, to channeling one’s ancestors. They also serve in BDSM and war (to say nothing of public health epidemics) to humiliate and objectify the “other,” reducing her to an animal or pure spectacle. After months of sadomasochistic rituals, the character “O,” in Anne Desclos’ The Story of O, is presented to a crowd wearing an owl mask, a chain attached to her labia piercing—journalist François Chalais accused the novel of “bringing the Gestapo into the boudoir.” Whether beaten beyond recognition, masked, or erased, the face is the signature of our humanity and singularity, its genetic imprint, as well as the experience it reveals.

For Rilke, seeing a face stripped of personhood is as much a burden on the witness as on the subject herself:

I could see it lying there: its hollow form. It cost me an indescribable effort to stay with those two hands, not to look at what had been torn out of them. I shuddered to see a face from the inside, but I was much more afraid of that bare flayed head waiting there, faceless.

2. Fateless

The plasticized, cosmetically altered, botoxed, and made-up face is not only immobile, but interchangeable with other Hollywood molds. One thinks of the rubber faces of classic stars such as Greta Garbo or Lucille Ball, who manifested theatricalized jouissance on the shifting features of their face. To be without a face, or to be seen as indistinguishable from members of one’s family, racial, or ethnic group, is also to lack a name beyond the generic Althusserian placeholder “Hey you!” Without a face, or a name—restricted to the pursuit of beauty, domestic duty, sexual objectification, or alienated labor—how can one begin to claim passions, purpose, or destiny? As Sebastien Barry writes of the inspiration for his novel The Secret Scripture:

We were driving through Sligo, and my mother pointed out a hut and told me that was where my great uncle's first wife had lived before being put into a lunatic asylum by the family. She knew nothing more, except that she was beautiful . . . She was nameless, fateless, unknown. I felt I was almost duty-bound as a novelist to reclaim her and, indeed, remake her.

A photo of Frida Kahlo in 1932 by Guillermo Kahlo (1871-1941). Image: Wikimedia Commons.

3. The Inner Frida

The open, inviting, non-threatening gaze of bourgeois female sitters portrayed in countless paintings—think Monet, Renoir, Matisse—participate in the fetish of the tamed and commodified female body, in whose nude figure and blank visage fears of the unconscious and the exotic are quelled. “Is this fascination merely an exploitative pleasure in the contemplation of an exotic, unconscious, and narcissistic femininity, whose display compensates for the sensual deprivations of the puritan North?” asks Kate Chedgzoy, in her essay “Frida Kahlo’s ‘grotesque’ bodies.’” “That is, are we using Kahlo’s work to assuage our own lack? Or is it possible that, in the recognition of the other woman’s subjectivity—be it suffering, self-absorbed or revolutionary—which Kahlo’s work offers us, a more truly liberating and intersubjective dynamic can come into being?”

Provisional resolutions of antimonies between high aesthetics and popular art, between unmediated nature and the aggressive manipulations thereof (biopower reduced to an instrument for genetic reproduction), arise from the work of artists like Kahlo who reject the image repertoire of the ideal female imaginary. These artists (think Cindy Sherman, Marina Abramović, Ana Mendieta, Catherine Opie, Cathy Cade, Laura Aguilar) refuse both victimization and pop art ubiquity—Warhol’s “binders full of Marilyn”—yet their Ashberian (albeit feminized) convex mirrors are not designed to entertain or soothe. “The socialized body is opened by instruments, technologized, wounded, its organs displayed to the outside world,” says Jean Franco. “The ‘inner’ Frida is controlled by modern society far more than the clothed Frida, who often marks her deviation from a norm by defiantly returning the gaze of the viewer. The naked Frida does not give the viewers what they want—the titillation of female nakedness—but a revelation of what the examining eye does to the female body.”

To learn to see the frame that blinds us to its interiors is no small matter. If nudity, as Georgio Agamben says, is unconcealment, the absence of all veils, or the gaze into a clear mirror or “subject wholly subject,” however abjected, then an aperture into truth, or sight beyond illusion, could be a re-framing of the subject, or a transcultural space allowing for the co-existence of two subjects. Whether contemporary religious veiling is an extension of female modesty and protection from the public sector or symbol of patriarchal oppression remains a highly contested issue, with many religious sanctions denying women of first, second, and third world countries agency, reproductive rights, education, and economic exchange.

El Quipu Menstral, by Cecilia Vicuña. Image: ajisabel.

4. The 3-D Face

Sculpture: a human body’s likeness, frozen for eternity, as a static mirror. Sculpture’s logic is commemorative, akin to that of the monument; a modernist view of sculpture situates the genre between landscape and architecture, as an oppositional third space or term. Occupying the schism between site and event, sculpture enacts the rupturing of medium, and is therefore emblematic of the crisis and kinetic potential of postmodernism or conceptual art itself. The délire de toucher is one passion that Western culture safeguards us against, from the hushed sanctuaries of museums to the antiseptic learning environments of our public and private institutions, which “teach to” every sense except the kinesthetic.

The path of the sublime can be traced from the rhetorical sublime of the Greeks, to the dynamic and mathematical sublimes of Kant, to the autonomous sublime of modernism, to negative and technological sublimes—Žižek’s sublime object of ideology, latent content or meaning situated between dream-work and commodity-form. The sublime’s excess of signifiers is now represented by digital technologies, its fragmented “body” that of the cybernetic hyper-subject in constant flux, the farthest point yet, after GMO engineering, from pre-industrial cycles of production and an affectual charge, or projected image, of wholeness.

Postmodernity’s derealized body is a problem not just for individuals, our teetering globalized economy, cultural theory, and environmental studies, but for aesthetics. “Bold lover, never canst thou kiss”: John Keats bemoans the fate of the dispassionate figures of antiquity on an urn while admiring their Grecian perfection. Sculptor Cecilia Vicuña refers to the ghosted hand of sculpture as the “memory of the fingers,” a “re-membering” of the body in the creation of sculpture, installation art, performance art, and the book arts, particularly poetry.

Olympia, by Édouard Manet. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

5. Olympia’s Confrontational Gaze

John Berger’s seminal Ways of Seeing (1972) contributed to feminist readings of popular culture through essays that focus particularly on depictions of women in advertisements and oil paintings. For women, the power to see rather than be seen as a sexualized object is denied, Berger argues, forwarding evidence that only twenty or thirty old masters depict a woman as herself rather than as a subject of male idealization or desire. An idealized promise of erotic fulfillment for the viewer is a substitution for the social reality depicted.

Olympia, by Édouard Manet, first exhibited at the 1865 Paris Salon, marks the beginning of a deviation, however fraught, in this history: fraught because the figure is accorded visual agency, yet still depicted nude, and prostrate, lying on a bed as flowers are delivered by a female servant. In 1890, the nation of France acquired the painting, now on display at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, after a public subscription organized by Claude Monet. The painting’s two subjects are a black maid and a young, white girl, establishing race relations as they occur in domestic life (in contrast to Paul Gauguin’s exotic and fetishistic tableaux of Tahitian women, from the same period). The painting employs an Edenic motif—Olympia covers her privates with her left hand as the servant presents her with a bouquet of flowers—the action appears as a courtly gesture, as if the flowers were from a suitor, not a client. The painting, based formally on The Venus of Urbino by Titian, was brazen in its time for displaying a courtesan at rest. Prostitution was a fact of life or double-life for many middle- and upper-middle class men, but prostitutes were not usually among the women depicted (Mary, art deco goddesses, wives of patriarchs or the painters themselves) in fine art.

As a figure, Olympia is not autonomous, but, rather, a commodity, yet her gaze is Edenic, shameless even, suggesting that agency begins not with social or economic freedom, but with the freedom to determine one’s perspectival gaze.

6. Being Beloved: A Recipe for Survival, or Death?

“The death then of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world,” Poe said. Despite feminist strides toward closing the wage gap, ensuring reproductive freedom, and protecting women from violence, the international news is still flooded with stories of honor killings, stonings, rapes, and murders of women and young girls, and world literature is still rife with swan songs of doomed women (Cassandra, Ophelia, the Lady of Shallot, Annabel Lee).

Death is the mother of beauty, as Wallace Stevens said, positing the feminine as a sacrificial offering for the continuance not of the species, but of the aesthetic ideals of the West—ideals invested in half the species continuing an industrial-military program of conquest and dominance. Women participate today, more than ever, in value production and in the general economy, but primarily with unpaid domestic work and underpaid service work, not as arbiters of their own value. Face it: to be female is still, often, to be dispossessed of authoritative language and the ability to name.

According to Levinas, the face, in its nudity and defenselessness, signifies “Do not kill me.” Before we learn (or unlearn) the psychosomatic practice of body armoring, this defenseless nudity is a resistance to metonymic erasure, beginning with one’s imprint of singularity, of identity: the face. The face’s expression, moreover, carries with it this combination of resistance and defenselessness: Levinas speaks of the face of the other who is “widow, orphan, or stranger.” Similarly, psychotherapist Julia Kristeva describes the abusive relationships a female patient from North Africa has with men as originating in a father’s tyranny so destructive that it has literally effaced the role of the mother and of the woman for her: “this patient has no image of her mother’s face, and can only have sado-masochistic relations with men, which are necessarily violent and demeaning.”

There can be no face without a head, nor sense without a brain: in Sylvia Plath's 1963 novel The Bell Jar, the protagonist reacts with horror to the “perpetual marble calm” of a lobotomized woman. Images of beheading, effacement, and disfigurement are central to the work of Georges Bataille, who was ejected from the surrealists for his too-violent renderings of the eponymous “exquisite corpse.”

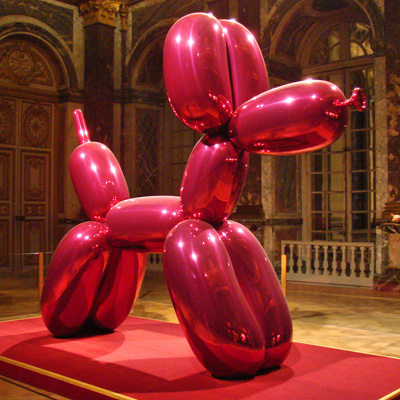

Balloon Dog, by Jeff Koons, exhibited in Versailles. Image: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra.

7. Survival of the Prettiest

Little, big, grotesque, ideal; episodes in the passage of woman from goddess to abject prostitute to June Cleaver’s 1950s domestic beatitude—spatula (prosthesis for a phallic signifying wand?) in hand—are legion, and all center on shifting perceptions of women: as decorative object, as gamine tomboy, as robust mother figure, as svelte femme fatale. We live in a Darwinian culture of the survival not of the smartest or most skilled, but the prettiest, as Nancy Etcoff notes regarding the “science of beauty.”

Ostensibly the opposite of pretty, the dirt-stained canvases of Oscar Murillo and the balloon toys and iconic figures of Jeff Koons are more concerned with the mutations, transmigrations, and cultural codings of subjects and objects than their reification as “art.” Extreme instances of invested labor (Murillo) and commercial investment (Koons), their work highlights the Duchampian reduction of aesthetics to arbitrariness, as if there could be artworks that are not only intentioned or conceptually-driven, but coming into being from an a priori form, or from divine rather than natural order—what David Geers describes as a work that can pierce the image stream or signifying chain by “outshining its spectacle.” This object could, ostensibly, transcend the context that supplies it with meaning, manifesting not a market value but an “intrinsic” value that exceeds a man-made criterion or standard of beauty: an art form, in other words, that, in its being-becoming, survives the aesthetic, philosophical and scientific “burden of proof.”

Geers asks, “What would it mean to appeal to a gold standard in art? . . . We see it in any number of works that index their value by imitating jewels or precious metals (e.g., Rudolf Stingel, Rashaad Newsome, or Jacob Kassay); in traditional artists of the ‘atelier movement,’ who uphold classical, ‘timeless values’; and ultimately, in Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God (2007), a $100 million, diamond-encrusted skull that confuses aesthetic values with materialist ones.” The trouble with appealing to a gold standard in aesthetics is a problem of the Hegelian sort—to delineate between the symbolic and the real is to compromise the imagination, as shelter and life-force, and to perpetuate a dialectic between being and becoming, between the actual and the non-existent. It is a death-knell, in short, when any criterion or standard of admission, like a dead metaphor, fundamentalist interpretation, or unamended Constitution, is not subjected to a democratic process, nor conceived as a living form.

Girl with a Pearl Earring, by Johannes Vermeer, 1665. Image: Wikimedia Commons

8. The Real: A Satori in Which Words (and Money) Fail

When my mother’s subsequent operations resulted in more than just facial paralysis (epilepsy, issues with balance and coordination, memory loss), I didn’t see her as damaged. The love she had always given me was not measured against a physical maternal ideal or “good breast,” as many psychotherapists would have it; I was grateful for each conversation and act of care she showed me, and remain so to this day.

“Why is the measure of love loss?”asks Jeanette Winterson. Why, in capitalism, are lack, absence, credit, suffering, and death equated with profit, and why are economies of exchange, reciprocity, and eros—at least in Western literature and religion—foresworn?

Scopophilia requires a subject to be watched—requires a body to be “delivered up” to the spectacle without even her knowledge or consent. As Žižek said, “Perhaps, in a sense, there is no greater violence than that suffered by the subject who is forced, against his or her will, to expose to public view the objet a in himself or himself. And, incidentally, therein resides the ultimate argument against rape.” What is rape culture other than institutionalized enforcement of neo-colonial power, wherein those lacking agency—lacking even an “I,” let alone a safe word—are often faced with two choices: feign a desire for degradation (e.g. Fifty Shades of Grey), or cultivate the art of anhedonia (refusal to seek pleasure)? Sex will always sell. As will ruin porn, Girls Gone Wild, and any media spectacle based on the backwards logic of capitalism: surplus, and pleasure, are only achieved if the majority go unpaid, suffer, or die.

Nonetheless, maybe there remains an alternative to fusion with an abyssal mirror or the pleasures of scopophiliac culture, wherein our gaze and the gaze of others is seemingly without bounds, a cruel theater of surfaces or illusions, and, in cyberculture, a theater deprived of other sensory modalities and any sense of antecedent or consequence of our actions. If all images are airbrushed, mediated and simulated so as to eliminate the texture of the real, the remaining question is where the “real” inheres in light of the unanswerable problem of Western aesthetics, that of establishing an externalized locus or objective criterion for subjective perceptions of quality and taste. If beauty remains in the eye of the beholder, and marketing trends are dictated not by the market but the consumer, now is as good a time as any to divest from the industries and media fodder that keep us twice-alienated from ourselves, the other, and intimacy.

“At the end of the word there is silence, at the end of silence there is the gaze,” as Elie Wiesel says. Could this trajectory also be reversed: could the society of the spectacle and the cult of the image end when print culture and textual literacy reassert their survival? Maybe the mysteries of transpersonal psychology—you seeing me seeing you—and personal reconstitution in the non-acquisitive, loving gaze of another, could reestablish a logic of co-presence and mutual recognition, rather than negation: the beginning, one hopes, with however rose-tinted an optimism, of an ethical-aesthetic reconnaissance.