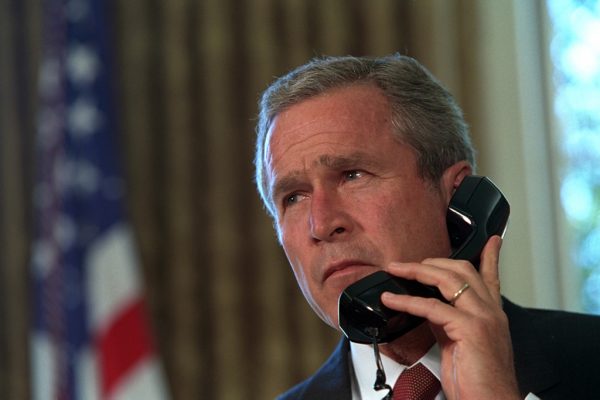

“Dwelling in grief . . . is harder than assigning blame,” Ingrid Norton wrote in our pages for the fifteenth anniversary of the September 11 attacks. Five years later, as the War on Terror continues, it seems that 9/11 still persists as a loss to be avenged rather than one to be mourned. Indeed, as Joseph Margulies argued fiercely this week, the normalization of previously unimaginable forms of barbarity has continued apace for the past two decades. “Anyone glancingly familiar with U.S. history knows that Americans have always had a refined capacity for cruelty,” he writes. “But 9/11 unleashed a particularly virulent strain of the impulse to believe that some among us are less than human”—just ask Abu Zubaydah and others tortured by the CIA at Guantánamo.

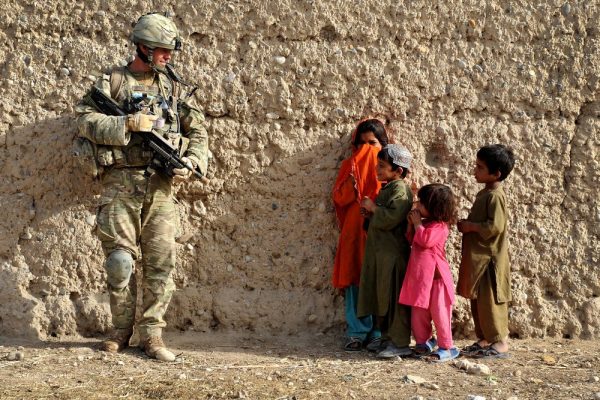

In another new essay, Madiha Tahir makes clear that while U.S. troops have left Afghanistan, this is less a withdrawal than it is a redistribution of imperial power. “The United States is dispersing its war-making to collaborators and security assemblages that will help render empire difficult to track,” she writes. This is a game that the United States has long played in Pakistan, where local forces have collaborated on drone bombings and overseen secret detentions and disappearances at the behest of U.S. empire. The work of the late historian Nasser Hussain also draws connections between the mechanisms of the War on Terror and the wider colonial regimes that shaped it. Originally penned a decade ago, his noted essays on drone strikes and counterinsurgency efforts were recently republished with a new introduction by Atiya Husain.

Other archival pieces round out today’s reading list, many written in the weeks and months following the September 11 attacks. Philosophy is well represented, with Sadiq Al-Azm exploring Western dominance and the Arab imagination, and Diego Gambetta probing alarmist and irrational thinking, asking “has 9/11 made it hard to think straight?” Security and surveillance feature heavily too, including David Cole’s forum on civil liberties and Matthew Longo’s essay on citizenship after 9/11. In addition, many of the essays below have become some of the most noted works in the Boston Review canon, including Noam Chomsky on how intellectuals can use their privilege to challenge the state, Elaine Scarry on democracy and self-defense, and Corey Robin on post-9/11 political opportunities and the class of political elites that benefited.

More recently, contributing editor Adom Getachew explored three frameworks for handling international crises that emerged in 2001. While the War on Terror and an ill-defined “responsibility to protect” struggling countries have both failed, the Caribbean movement for reparations may have something to teach us. “It draws our attention to the persistent entanglements between the domestic and international realms of politics,” she writes, “urging us to consider what responsibility means in the face of everyday political, economic, and social crises.” Indeed, as the U.S. departs Afghanistan, leaving behind a mess of corruption and violence, it’s clear that the claims of humanitarian compassion ultimately were empty. “Humanitarianism is accountable only upward,” Faisal Devji wrote last week, “to an organization’s donors and stakeholders or a foreign government, instead of downward to its beneficiaries.” It’s time to move on from this violent logic of colonialism. We hope the pieces below can help in forging a new path forward.

Drone attacks were sold to the American people as a way to limit U.S. involvement in Pakistan. In reality, U.S. empire has only continued to exert influence.

The UN's “responsibility to protect” framework has failed to achieve a just international order. The Caribbean movement for reparations points the way forward.

From drone strikes to counterinsurgency efforts, the work of the late historian Nasser Hussain highlights the importance of understanding the mechanics of the War on Terror, not just its effects.

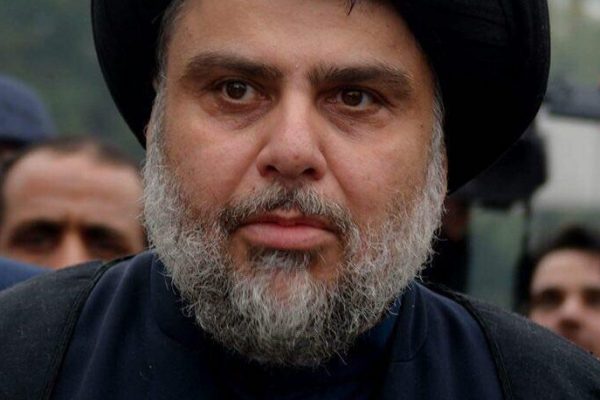

Far from a relic of the past, September 11 continues to normalize state-sanctioned barbarity.

Forum

As politically tempting as the trade-off of immigrants’ liberties for our security may appear, we should resist it for reasons of principle, pragmatism, and self-interest.

We have surrendered the cherished value of “innocent until proven guilty” for the security logic that we are all “risky until proven safe.”

The U.S. occupation of Afghanistan sacrificed politics—the only viable route to peace—for massive corruption and violence.