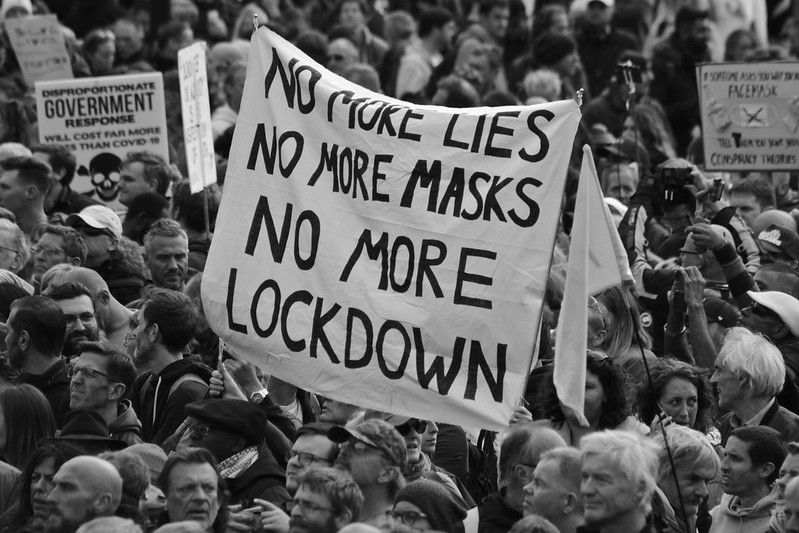

Often held up as a beacon of liberal democracy, West Germany experienced a “spasm of magical thinking” in the decades following World War II. Between 1947 and 1956, there were 77 witchcraft trials, and the new country’s newspapers were full of reports of witches and medicine men roaming the countryside. Fast forward to 2021 and similar trends are being identified. Blending cynicism toward parliamentary politics with a dose of spirituality and dogged discourse of individual liberties, Germany’s Querdenken movement—in favor of “diagonal thinking,” as William Callison and Quinn Slobodian explain—argue that the media and the state are working to create excessive fear in the population, conceal the truth, and deceive the people.

Sound familiar? While enduring vaccine hesitancy and the storming of the Capitol on January 6 are often discussed under the narrow label of Trumpism, there is a broader global phenomenon at play when it comes to conspiratorial thinking. For intellectual historian Nicolas Guilhot, it’s a trend that must be understood from a social and political lens, rather than with a focus on the faulty reasoning of individuals. Contrary to historian Richard Hofstadter’s famous indictment of the “paranoid style of American politics,” the psychopathology of the conspiratorial mind reflects real problems with society writ large.

Other essays from our recent archive take this argument seriously, especially when it comes to science. Philosopher Michael Patrick Lynch makes the stakes clear. “We cannot afford to ignore how knowledge is formed and distorted,” he writes. “We are living through an epistemological crisis.” One question we might ask is: Where do you place the boundary between science and pseudoscience? For historian Michael D. Gordin, the solution is far from obvious, but we can do better than Karl Popper’s criterion of falsifiability.

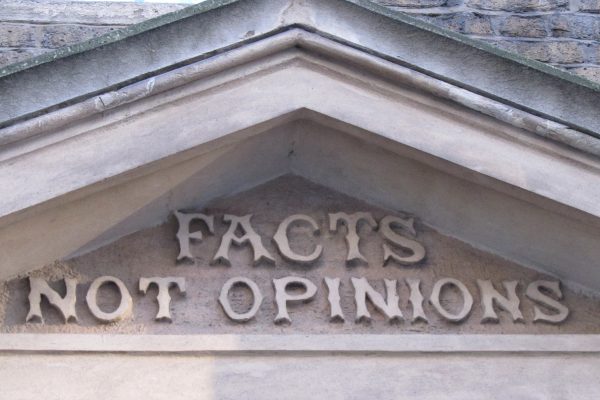

The question is also more than academic. Indeed, as unproven cures and preventatives for COVID-19 continue to pop—ivermectin taking center stage most recently—it’s clear that tolerating pseudoscience can cause real harm. But as the debates over hydroxychloroquine in the summer of 2020 showed, it’s not entirely clear-cut. “Trumpeting hydroxychloroquine is undoubtedly risky,” wrote philosophers Cailin O’Connor and James Owen Weatherall, authors of The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread. “But sharing anecdotal accounts of its success in various clinical settings is not necessarily misinformation—and neither is sharing information about failed clinical trials.”

In “How Americans Came to Distrust Science,” historian and author of Science under Fire Andrew Jewett makes clear that suspicion of science is not new in U.S. society—and at times, indeed, it is warranted. “For a century, critics of all political stripes have challenged the role of science in society,” the piece reads. “Repairing distrust today requires confronting those arguments head on.” In an essay growing out of his work on a special issue of the Hastings Center Report on the prospects for repairing this crisis of distrust, editor Gregory E. Kaebnick corroborates that science is far from infallible, and as such it is crucial that any efforts at repair do not rely on unqualified deference to experts. Instead, he argues, we must “empower citizens to deliberate about issues, make decisions, and shape policy.”

Guilhot weaves together similar observations about trust and knowledge with urgent political analysis. “If we are concerned about the spread of conspiracy theories,” he writes, “we should realize that debunking is a distraction, a Whac-A-Mole game for fact-checkers and information watchdogs. Instead, we should address the dearth of political vision on which conspiracism feeds.” The solution will entail a wholesale transformation of our economic and social arrangements—not simply critical thinking efforts meant to make people more “rational.”

We should blame conspiracy theories like QAnon on politics, not the faulty reasoning of individuals.

Defying conventional political labels and capitalizing on widespread distrust, a range of new movements share the conviction that all power is conspiracy.

West German witchcraft trials after World War II reveal how political rupture can fuel magical thinking.

For a century, critics of all political stripes have challenged the role of science in society. Repairing distrust today requires confronting those arguments head on.

Its authority derives not from unbiased scientists but from the institutions and norms that structure their work. Fighting mistrust requires more public engagement with policy, not unqualified deference to experts.

At a time of anxiety about fake news and conspiracy theories, philosophy can contribute to our most urgent cultural and political questions about how we come to believe what we think we know.

On the fate of Karl Popper’s idea of falsification.