The legendary Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank died this week. Best known for his 1959 black-and-white collection The Americans, Frank documented the jarring gap between progress and poverty in postwar U.S. society, substituting looks at actual life for the aspirational iconography of Leave It to Beaver. “I think people like the book because it shows what people think about but don’t discuss,” he once said. “It shows what’s on the edge of their mind.”

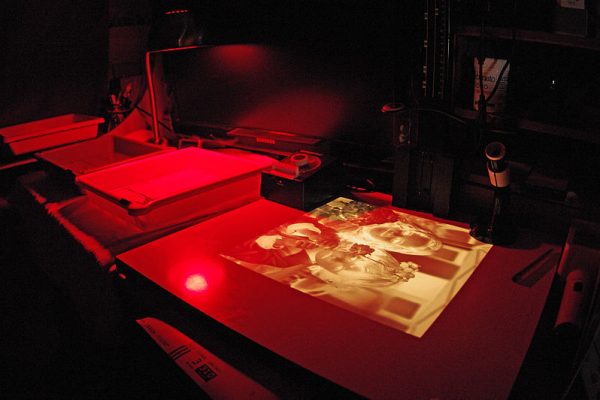

This week’s reading list bears him out, reminding us that the photograph has always been a contested medium—operating at the edges of the present and the possible, the marginal and the mainstream. It has also been a permanent fixture in the pages of Boston Review—not just as a work of art but as a mode of journalism, a form of knowledge, and an instrument of political power.

Susan Sontag, writing in our very first issue in 1975, reflects on photography as an “imperious way of seeing,” while Daniel Penny, writing in 2017, confronts the commodity aestheticism he finds resurgent in the age of Instagram. In between, critics offer readings of the work of Rosamond Purcell, Robert Capa, and Larry Sultan, and many explore what it means to look at images of violence—from the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the horrors of the Holocaust to the ongoing crisis in Kashmir and contemporary police brutality.

Through it all, we are invited to ask, as Susie Linfield puts it in her searching analysis of photojournalism, “Do we approach the photograph as spectators, or as citizens of the world?”

—Matt Lord

Geoffrey Movius speaks with Susan Sontag about photography, writing, and memory.

For many critics, photography has become a duplicitous force to be defanged rather than an experience to embrace.

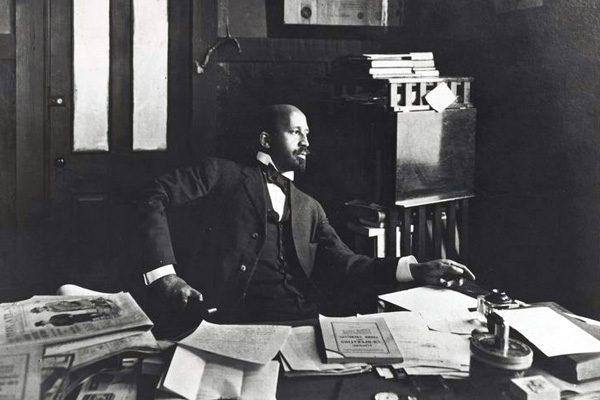

Images of police violence against African Americans have a radical heritage.

Do we approach the photograph as spectators, or as citizens of the world?

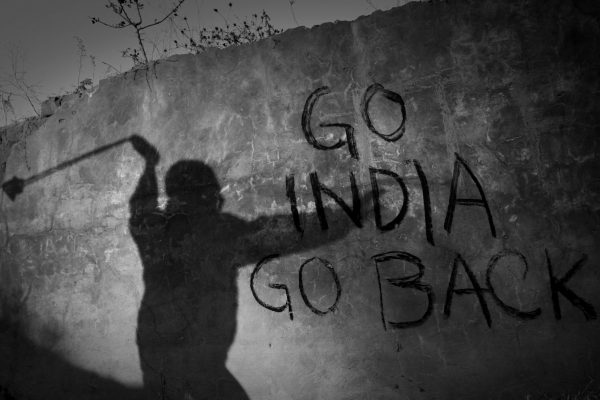

From scrapbooks to family albums, a new book presents their visual testimonies from Kashmir.

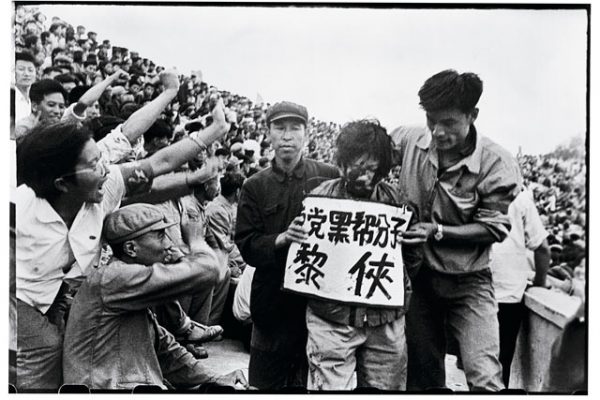

In the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the weapon of choice was not the gun but the spectacle of public shaming.

The modes of perception and living that we attribute to Instagram are rooted in a much older aesthetic of the picturesque.

The photographer wanted to show what freedom, and the people who made it, looked like.

Heinrich Jöst’s photographs of the Holocaust dwell in what Jean Améry called “the waiting room of death.”

Larry Sultan’s elegiac photography captures the suburban American home.