Just over forty years ago the Supreme Court struck down race-based quotas in school admissions while also upholding the core tenets of affirmative action. In the landmark 1978 decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., singled out Harvard’s admissions program as an exemplar for achieving diversity and applauded the university’s own description of its policy, according to which the “race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates’ cases.” As the Supreme Court would later emphasize, such review considered race merely a “factor of a factor of a factor.”

Harvard’s policy is now being challenged in federal district court in a suit that could reshape the role of race in college admissions.

In past efforts to dismantle affirmative action—from Bakke to, most recently, a case brought by two white women against the University of Texas—the plaintiffs have alleged that race-conscious admissions policies hurt white applicants. But courts have consistently held that race may be employed to achieve the educational gains that stem from a diverse student body when considered “holistically,” as one among many factors. The latest legal salvo takes a different, and potentially more potent, tack. The litigants argue that Harvard, in its quest for racial diversity, unjustly penalizes a minority group: Asian Americans.

It is easy to get lost in the nuances of the competing arguments and counterarguments, with expert statistical reports and rebuttals clocking in at over 700 pages. (We know: we read them.) Though they don’t always admit it, the experts agree on some broad empirical patterns.

Past efforts to dismantle affirmative action alleged harm to whites. The latest salvo takes a different tack, alleging harm to a minority group: Asian Americans.

The main disagreement is one of interpretation: what factors a university can legitimately consider when making admissions decisions. Backed by conservative activist Edward Blum (who also spearheaded the Texas challenge), the plaintiff group, Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), advocates for a narrow focus on academic achievement. Harvard, on the other hand, has stressed the importance of non-academic factors, including athletics, character, and family connections. The impasse touches on deep statistical and legal questions of discrimination, merit, and the mission of elite universities.

Asian Americans and Academics

The Harvard case follows a half century of significant demographic shifts in the United States. Since 1970 Asians have increased from less than 1 percent to nearly 6 percent of the U.S. population. After decades of exclusionary policies, immigration reform in 1965 opened the door for Asian immigrants. Those reforms favored skilled and educated workers, helping to create a large pool of high-achieving Asian American students in subsequent generations.

Set against these demographic changes, Harvard admissions data reveal troubling patterns, SFFA argues. Over the past several years, Asian Americans comprised 27 percent of domestic applicants to Harvard but only 22 percent of domestic applicants accepted for admission; and just under 6 percent of Asian American applicants were admitted, compared to 8 percent of whites. But Asian American applicants had academic credentials and extracurricular track records that were, on average, stronger than those of other racial and ethnic groups, including whites.

SFFA alleges that this disparity indicates a discriminatory double standard, with Asians paying an unfair price for their race—in violation of the Civil Rights Act. Harvard counters that academic achievement is not the sole basis for admission. Indeed, the university receives far more applications from students with stellar high-school transcripts and SAT scores than they could possibly admit. For example, Harvard admits about 2,000 students each year, but more than 8,000 domestic applicants for the class of 2019 had perfect grade point averages (even after Harvard calculated the numbers according to its own index, in order to account for inconsistencies in the way high schools report grades). Rather than mechanically accepting academic superstars, Harvard aims for what it calls “distinguishing excellences,” taking an expansive view of talent that goes well beyond a student’s grades, test scores, and even extracurriculars.

After accounting for these distinguishing excellences, Harvard argues the apparent penalty against Asian American applicants disappears. SFFA argues that consideration of these factors is simply a veiled effort to limit the number of Asians on campus, a way to sidestep the long-standing prohibition against explicit racial quotas.

“Distinguishing Excellences”

Much, though not all, of the observed disparity in acceptance rates between Asian American and white applicants stems from Harvard’s open preference—which it shares with many elite colleges—for strong athletes and the children of alumni, faculty, and donors, all groups that are disproportionately white in Harvard’s pool of applicants. Whereas Harvard’s overall acceptance rate is about 7 percent, the college admits 86 percent of recruited athletes and 34 percent of “legacy” candidates—those with a parent who attended Harvard. Legacies account for 22 percent of white admits but just 7 percent of Asian American admits.

Yet setting aside legacies and athletes, Asian American applicants are still admitted at lower rates than whites with comparable academic and extracurricular records.

This remaining disparity largely boils down to admissions decisions based on personality, geography, and family. Harvard assesses the “personal” qualities of applicants on a scale from 1 to 6 (“outstanding” to “worrisome”), and on this dimension Asian Americans are rated lower on average than whites. Harvard officials describe “personal quality” as “a subjective determination of a combination of many, many factors,” including “perhaps likability, [and] character traits, such as integrity, helpfulness, courage, kindness.” The university likewise considers where applicants live and their parents’ occupations. Harvard may, for example, favor students from rural communities and disfavor the children of engineers.

Adjusting and Over-Adjusting for Differences

In many studies of discrimination, race-based or otherwise, an apparent disparity disappears once one accounts for other factors. In Harvard’s case, the gap in admissions rates between Asian Americans and whites largely vanishes after adjusting for differences in legacy status, athleticism, personal ratings, geography, and parental occupation.

Even if a variable helps to explain away a disparity between groups, that variable may itself be the product of discrimination.

In assessing whether Harvard intentionally discriminates against Asian applicants, a key question, then, is whether the factors the university uses to guide admissions decisions are themselves appropriate. If personal ratings were awarded in racially discriminatory ways, it would be inappropriate to appeal to them to explain disparities in admissions. Likewise, if personal ratings bear little relation to legitimate educational goals, then differences in admissions rate should not be justified by differences in the ratings.

This statistical issue—where controlling for illegitimate factors masks evidence of discrimination—is an instance of what is sometimes called “included-variable bias” (as opposed to the inverse problem of “omitted-variable bias,” which entails leaving out variables that ought to be included). In our own research on stop-and-frisk policing, we find that one can underestimate racial bias by improperly controlling for factors such as an officer’s judgment about whether a suspect is behaving “furtively,” since such judgments are often related more to race than risk.

In short, models can be misleading not only for the variables they omit, but also for the variables they include. Even if a variable helps to explain away a disparity between groups, that variable may itself be the product of discrimination or have little rational relation to a legitimate policy goal.

The Evolving Meaning of Merit

To gauge the appropriateness of Harvard’s admissions criteria, SFFA emphasizes the historical context of the university’s current admissions practices, which sociologist Jerome Karabel has exhaustively traced back to anti-Semitism in the early twentieth century.

At that time, Harvard formally and primarily relied on entrance exams to select students. But alarm arose when Jewish applicants began to be accepted in large numbers, often out-performing their wealthy Protestant counterparts on these exams. Harvard’s then-president, A. Lawrence Lowell, controversially proposed capping Jewish enrollment. Instead the university shifted its admissions to focus on the “character” of applicants, as well as geographic diversity and legacy admissions, achieving Lowell’s end by using different, less explicit means.

Harvard argues its current admissions practices are distinct both in form and in function from those of its discriminatory past. Karabel himself disclaims the relevance of former anti-Semitism to the SFFA lawsuit. But this history can unsettle ideals of well-roundedness and the need for holistic admissions to make suitably individualized decisions.

When it comes to discrimination, the relationship between intentions and effects is a subtle but important one. As Harvard has previously indicated, its contemporary preference for legacy students is intended to foster the alumni community and encourage donations, not to curb admission of racial and ethnic minorities. Nevertheless, favoring legacies benefits a disproportionately large subset of white applicants while leaving less space for the vast majority of black, Hispanic, and Asian applicants without family ties to the university, raising concerns about equity.

A similar problem plagues the university’s focus on athletics. Whereas holistic admissions originated in anti-Semitism, values of student athleticism are rooted in an ideology of “muscular Christianity,” the notion that manliness and moral leadership go hand in hand. When former Harvard president Charles Eliot threatened in 1905 to abolish football for its brutality—player deaths were not uncommon at the time—Theodore Roosevelt intervened, pledging to make the sport safer without it becoming “too ladylike.” In contrast to university systems abroad, American colleges place a marked emphasis on athleticism and the character-building aspects of organized sports.

Broadcast collegiate sports may be racially diverse, but athletic preferences at elite colleges appear mostly to benefit white applicants. At Harvard, about three-quarters of athletes admitted are white. As Saahil Desai has written in The Atlantic, selecting students for lacrosse, golf, sailing, and water polo may be a “quiet sort of affirmative action for affluent white kids.”

Despite these critiques, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights has previously concluded that it is permissible for colleges to give preferential treatment to both athletes and legacies. It is unlikely that view will change anytime soon. (President Trump’s Department of Justice did file a brief in the Harvard case, but while mentioning athletic and legacy preferences, it took no position on them.) SFFA largely concedes this point, focusing its argument on the disparity that remains after adjusting for differences in athletic recruitment and family connections.

Character and Bias

The use of personal ratings is one of the most controversial aspects of Harvard’s admissions process. Regardless of whether one believes Harvard should consider personal traits, the measure itself may have problems, stemming in part from an inevitable entangling of subjective judgment, bias, and larger goals in the admissions process.

If personal ratings were awarded in racially discriminatory ways, it would be inappropriate to appeal to them to explain disparities in admissions.

The personal ratings look different depending on who awards them: alumni interviewers or Harvard’s internal admissions staff. On average, alumni give white and Asian American applicants similar ratings, but Harvard staff give whites substantially better reviews than they give Asian Americans. For the alumni-assigned ratings, 50 percent of Asian American applicants and 51 percent of whites were rated as having “very strong” or “outstanding” personal traits. But for personal ratings awarded by Harvard’s internal admissions staff, only 18 percent of Asian Americans were in the top group, compared to 23 percent of whites. White applicants received these top ratings about 30 percent more often than Asian Americans.

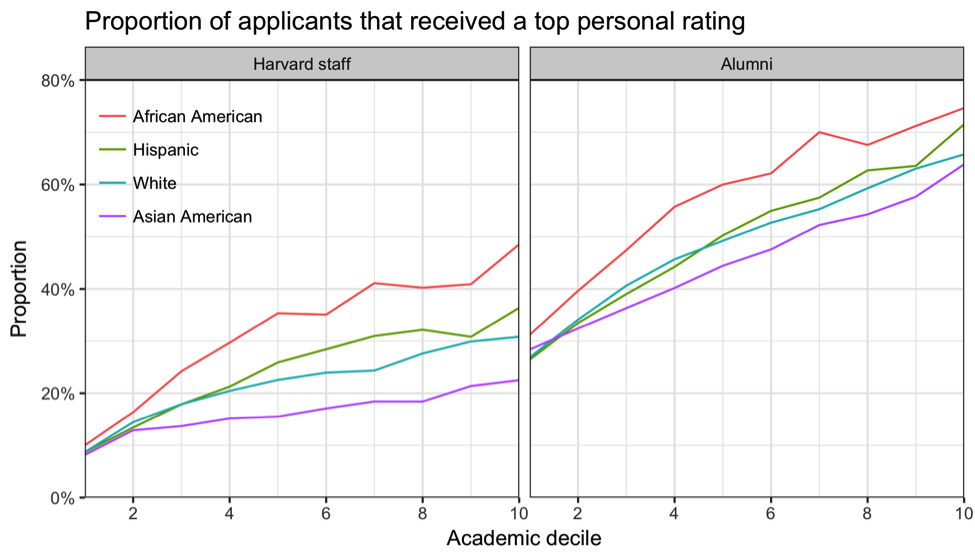

With acceptance rates well under 10 percent, most students have little chance of admission to Harvard. So it is important to look as well at the subset of academically competitive students, for whom personal scores may matter more. The graphs below show the percentage of applicants with strong personal ratings—in the top two categories of “very strong” or “outstanding”—broken down by academic performance.

On average, students with higher academic ratings get higher personal ratings. This pattern holds for all racial and ethnic groups and for both staff and alumni evaluations—and is perhaps worth studying in its own right.

Among the most competitive applicants, the graphs show that Harvard staff are still more likely than alumni to rate whites more favorably than Asian Americans. In the top academic decile of applicants, Harvard staff put 23 percent of Asian Americans and 31 percent of whites in the top two personality categories. In contrast, alumni interviewers gave this group of Asian and white applicants these top ratings at much closer rates (64 percent and 66 percent, respectively).

SFFA argues that these patterns indicate that Harvard staff manipulated the ratings or were otherwise biased against Asian American applicants. After all, subjective assessments such as “leadership potential,” “courage,” “grit,” and “fit” are particularly prone to subtle forms of discrimination. Harvard, on the other hand, claims its staff reviewers are simply more qualified than alumni interviewers to make such judgments, in part because they have access to more detailed information than the alumni.

A Path Forward

Adjudicating the competing empirical claims based on the expert reports alone is difficult for academic researchers, let alone judges. But we see three issues worth highlighting.

The Empirical Must Not Obscure the Normative

First, empirical questions must not obscure the more fundamental normative issues. Whether experts should adjust for factors such as personal ratings in their statistical models depends on normative assessments of how these criteria relate to Harvard’s educational mission. Consider that one of the contested factors is whether a domestic applicant was born in the United States. One might favor foreign-born applicants as a way of making the student body more geographically diverse, or disfavor such individuals to create a college cohort that better resembles a cross-section of Americans. Yet foreign-born status can also be a proxy for race. Qualitative grounding of statistical findings is important to avoid misleading conclusions; it is not enough to control for a factor in a statistical analysis without clarifying its role in admissions goals and educational objectives.

Warring Expert Reports Do Not Serve Justice

Second, when legal judgments rest on complex empirical analysis, courts are ill-served by warring expert reports. The two sides in this case analyzed different subsets of the data and used somewhat different statistical methods, making direct comparisons difficult. For example, some of the plaintiff’s analyses excluded applicants who applied early, and Harvard analyzed each yearly cohort of applicants in isolation. Both reports perform some analyses on all categories of applicants and some analyses that exclude special categories (e.g., legacies and athletes) that constitute a small fraction of applicants but a large proportion of admitted students. Such slicing and dicing can be problematic.

Our preference would have been to analyze all (domestic) applicants together, but in a way that would allow one to detect a potential pattern of discrimination that may differ across subpopulations—including groups defined by application cycle, ancestry, grades, and test scores. We have used that sort of analysis, termed multilevel modeling, many times in our own work, including to understand how the relation between income and voting varies by geography.

As we have learned from the replication crisis sweeping the biomedical and social sciences, it is frighteningly easy for motivated researchers working in isolation to arrive at favored conclusions—whether inadvertently or intentionally. As a partial solution, former federal judge Richard Posner has suggested that courts appoint independent experts to sift through the statistical evidence.

Admissions Criteria Should Be Made Clearer

Third, Harvard and other universities could work to better codify and align admissions procedures with institutional goals. If parental occupation, for instance, is merely a proxy for socioeconomic status, more direct measurement of socioeconomic status may reduce unwarranted discretion. The risk of such clearer, more parsimonious admissions criteria is that they may expose the value placed on race, running up against the Supreme Court’s distaste for race-conscious point systems in college admissions.

SFFA argues that Harvard should simply replace its affirmative action policy with an admissions plan that favors students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. In response, Harvard states that such alternative approaches “either are ineffective at generating a racially diverse class, or would significantly alter the composition of the admitted class along other dimensions.” Regardless, greater clarity in admissions criteria would help resolve statistical disagreements.

The Future of Affirmative Action

The core contention in this case is about the meaning of merit and its role in elite education. Both sides agree that even if one sets aside legacy applicants and recruited athletes, Asian Americans are admitted at lower rates than whites with similar academic and extracurricular credentials. Less clear is the role that “multi-dimensional excellence” (read: athleticism and “outstanding” personality), family background, and geographic diversity should play in college admissions—and accordingly in statistical assessments of bias—particularly if a focus on these factors favors whites over Asians.

The substantive legal and policy questions here have more to do with potential anti-Asian bias than with affirmative action itself.

SFFA’s stated goal is to end affirmative action. Harvard has defended it, triggering progressive support for race-conscious admissions and, at the same time, for Harvard’s side in this lawsuit. Yet those two things—affirmative action, on the one hand, and Harvard’s particular admissions practices, on the other—are not one and the same. The substantive legal and policy questions here have more to do with potential anti-Asian bias than with affirmative action itself. According to a dean at the University of California, Berkeley, Asian Americans are “being used as a pawn in a chess game.” Even if SFFA is right that Harvard’s admissions practices are biased against Asians, that does not mean affirmative action itself is to blame.

As a result, if the courts do find that Harvard has improperly discriminated against Asian applicants, one remedy is to simply curb that practice; they need not curtail long-standing affirmative action policies that increase the representation of underrepresented minorities on college campuses.

Editors’ Note: Gelman and Ho received their PhDs from Harvard, and Gelman has taught at Harvard as well. None of the authors has been involved in the SFFA lawsuit against Harvard, and they have no financial conflicts of interests.

Correction Notice: An earlier version of this essay included a potentially misleading sentence regarding a statement made by a dean at the University of California, Berkeley. The sentence has been updated for clarity.