“I’m a teacher,” I mumble under my breath. The instructor yells another command, and we collectively pull our triggers, setting off an angry crackle of handgun fire. Twenty-three paper intruders recoil quicker than senses can register. The entire scene has the atmosphere of sport; the targets do not bleed or shoot back. Squinting through the sun’s glare, I look for the impact point, the void that would bleed the life from my hypothetical foe.

After the Newtown shooting, parents demanded to know how we would protect their children; locked doors and security cameras were not enough.

“This person is killing your students!” an instructor berates, fuming at our inadequacy.

The humanoid targets are faceless, sexless, standing over six feet tall. An hour before, the instructors informed us that most school shooters are male students. But few students, even high school males, are this tall. On the range this comparison is unspeakable, but I can’t shake the thought: we are being trained for the contingency that we have to kill a student.

“Fire!” the instructor yells again. The barrage continues.

Standing on each side are my colleagues in public education. Teachers and administrators all—but this week, we are recruits training to prevent a school shooting. We are learning to use a gun and, if necessary, to kill. This last part is never spoken, betraying our instructors’ fear that educators may not have the mettle to take a life. On this first day of training, feeling utterly out of place, I am apt to agree.

A few months earlier, my district decided to arm staff members. According to a novel reading of Ohio law advanced by the state’s attorney general, Mike DeWine, in 2013, Ohio school districts have always had the option to arm teachers and do not need to make that choice public. Therefore, it is difficult to know how many districts have in recent years availed themselves of this option. Buckeye Firearms Association, an Ohio Second Amendment lobbying organization and PAC, claims that sixty-three of the state’s eighty-eight districts now have armed staff.

My district’s school board struggled with the decision. After the Newtown shooting, parents came to board meetings demanding to know how the district would protect their children; locked doors and security cameras no longer allayed their fears. It was easy to see that in recent school shootings, similar safety measures had proven ineffective.

Calls were made to neighboring districts and eventually Buckeye Firearms Association was asked to make a presentation to the school board. The presentation sharply divided the board’s members. For some, the choice was easy; for others, agonizing.

“How do you know that this person we arm won’t go off?” one board member shouted at no one in particular.

“How else can we protect students on our budget?” came a response.

I sat in the meeting, unsure how I would answer either question.

My life as an educator seems distant.

In his navy suit, Buckeye’s expert emphasized that it was a district decision and that we needed to do what was best for our students—even as his tone betrayed his conviction that every school in Ohio should have armed staff. He offered polished, if often unrelated, responses to the board’s questions: “It takes rural police an average of fifteen to twenty-two minutes to respond,” “Most school shootings last less than five minutes,” “Newtown was over in three.”

Before leaving, he placed a page of statistics before each member. The board gazed at the sheet in silence as he departed, then voted unanimously to send a staff member to the summer training.

Administrators were approached first. We were given the opportunity to opt out, to choose the sidelines. One principal declined, but I felt I had to go, not only for the students, and not only because it was expected of me, but because I felt that I needed to evaluate the training for myself from the perspective of an educator. More than that, I thought: better me than someone else. I felt safer doing it myself than letting the job fall to someone I would have limited say in choosing.

I signed a confidentiality agreement. The hope was that secrecy about who was carrying would prevent me from being targeted during a shooting. I received a list of the gear required for training and was reimbursed by the school for the purchases.

The white paper from Buckeye recommended Glock handguns. Glocks are almost guaranteed never to jam or misfire, it claimed. Having never owned a semi-automatic handgun, I simply took that advice. The district supplied a thousand brass-cased 9mm rounds for my training. After that it would provide hollow points, rounds designed to swell upon impact to ensure maximum harm.

The training is at a police firing range in northern Ohio. Rittman is the sort of town we all traveled from: rural and with little diversity. A Rust Belt burg with sulfur and coal dust in the air, few businesses remain in the small downtown. The locals are pleasant and pleased with our arrival. We are their stimulus plan, arriving in waves every two weeks.

The range is covered in pea gravel and shell casings, and is encircled with earthwork embankments that stand eight feet high and are thick enough to stop projectiles. It is isolating, like being at the bottom of the sea. Rising from the graveled seafloor is a pole barn which serves as a classroom. At this facility, we learn a new choreography from police veterans who spit their fevered instructions. The training is effective, and our progress is quick.

After the day’s shooting practice, we go inside the barn where Chris Cerino, the program’s creator and lead instructor, shows us videos. Chris is a hero to local law enforcement and is held in immediate and pious reverence by the new trainees. Chris is a world-renowned competitive marksman and two-time runner-up on the History Channel’s Top Shot. He is the closest thing in this area to a reality television star.

Red and blue lights from Chris’s videos fill the darkened barn as the distorted sound from body- and dash-cam videos blasts over small speakers. Each clip ends with shots fired and a policeman killed or wounded. Between clips, Chris explains the officers’ mistakes. The recurrent theme: “Don’t provide too many warnings. Determine the threat, then shoot or be shot.”

We learn how to shoot from police veterans who spit their fevered instructions. The training is effective, and our progress is quick.

A fellow recruit, Anthony, is brought forward and handed an airsoft pistol. He appears gangly and awkward next to Chris. His shoulders slump forward slightly and his shirt hangs loose while Chris stands rigidly at attention. Chris is right off of a recruiting poster; his barrel chest and square jaw give him the appearance of a comic book character. He makes Anthony look like Ichabod Crane.

Chris tells Anthony to raise the gun and fire at him. They stand, arms at their sides in an uncomfortable silence while Chris beckons Anthony to shoot him. Finally, Anthony raises the gun and shoots. Chris tries to anticipate Anthony’s movements and shoot first in what resembles a Wild West gunfight. After multiple attempts, it is obvious that even Chris can only achieve a tie, at best.

Chris says, “Reaction is slower than action, every time.” The adage will be repeated daily as a reminder to act before you are acted upon.

Chris starts up the videos again. They often end with officers screaming into their radio, sometimes for help, sometimes with last words for loved ones. The tone in the classroom changes after the videos, the playful banter extinguished. The day no longer resembles a professional conference, but a discourse on survival.

Chris’s assistant goes over statistics from recent shootings and then praises how the curriculum will work upon us. “From this moment forward,” he tells us, “you will canvas for the uncommon. You will view strange scenes as an indication of possible violence. You will never be afraid to act.”

The language is militaristic and foreign; a sense of dissociation washes over me, a kind of shock. As I sit listening to the assistant, my life as an educator seems distant.

We spend most of the second day shooting the paper villains. During breaks the instructors replace the tattered targets and we begin again. Blisters form on my hands early in the day, making each percussive recoil a test in pain management. I try to hide the wince that follows each shot; the atmosphere is full of male bravado, despite the participation of a number of female recruits, and visible weakness feels inexcusable.

We spend most of the second day shooting the paper villains. I am exhausted and my hands raw, tinted with dried blood.

Adding to the surreal quality of the day, a CBS news crew follows us around. The instructors say NPR will be in later in the week. When we are not shooting, the CBS crew asks questions while the program leaders troll for the next person to interview. When it is my turn, I feel the need to defend the program and my participation in it. It makes my interview stilted, which adds to my already heightened anxiety.

That afternoon, my accuracy becomes a problem. I am exhausted and my hands raw, tinted with dried blood. I see Chris walk toward me, scuffing the gravel beneath his boots until the crackling slows, then stops over my right shoulder.

“Let me see your gun,” he finally says after I pull another shot. “Keep looking at the target,” he says, taking the weapon.

I think about his stunt the day before, when he drew his weapon and shot upside down, pulling the trigger with his pinky. The demonstration was meant, I assumed, to show a recruit how poorly he was shooting. The result was demeaning more than anything.

I face the target until he returns the gun to me. I start firing again. Unsure of what he wants, my accuracy suffers further. When I squeeze off the third round, nothing happens. Nothing, that is, except for my body jolting forward in anticipation, and the “click” of the gun. Chris has replaced the third bullet in the magazine with a fired casing and I, in turn, have committed a cardinal sin. Jumping in anticipation is a sign of timidness, a mark against your manhood.

“No, no, no,” Chris yells, becoming so animated that recruits on each side of me stop and look. “You are anticipating your shots! No wonder you can’t hit shit!”

“Sorry,” I respond. “I don’t know why I started that.”

Chris stops his wild gesticulating, shaking his head slightly before allowing a grin to twist his mouth.

‘You are anticipating your shots! No wonder you can’t hit shit!’

“I do,” he says. “It’s an explosion right next to your head!” He lightly pokes my temple with his index finger. “This shit ain’t natural!” With that, he pats my shoulder and heads off.

The guy next to me smiles and shrugs. I watch Chris walk away, surveying the firing line, and think, “You’re right, this shit isn’t natural.”

We continue training for three more days, eight to twelve hours a day. We will be taking the Ohio Peace Officer Training Assessment at the end of the course. It is the same test required for Ohio police officers, but they are required to hit twenty-six of twenty-nine targets. As teachers, in a school setting and on the cutting edge of political upheaval, we are required to hit twenty-seven.

The group is visibly nervous upon hearing this, but by the end of the week we feel more secure in our abilities. The constant drilling has improved our skills; we begin to resemble the cops who train us. Our confidence grows.

We take the same test as Ohio police officers, who are required to hit twenty-six of twenty-nine targets. As teachers, we are required to hit twenty-seven.

Early in the week, the instructors seemed to yell constantly. They were regularly on someone for not following directions or not getting the procedures down as quickly as the rest of us. By Friday, though, they lighten up and share the occasional joke. This feels like an achievement. More significantly, we begin to feel as if we could defend our students.

The videos, instruction, and repetition play a trick on my mind, though. I start to think in terms of students and attackers, those I would protect and those I would kill. The latter are strangers— unnamed, faceless adversaries like the targets. My daydreams are no longer of classroom visits, sporting events, and kids making out in the halls. They are all adventure stories, and I am always the hero. An attacker is never one of my students. I never have to shoot one of my students.

The training encourages this result. Everything about its vocabulary is designed to dehumanize our aim. The instructors’ military language—“soft targets” and “areas of operation” for schools, “threats” for shooters, “tactical equipment” for guns—rubs off. On the final day, a pep talk analogizes students with lambs. We are the sheepdogs, charged with protecting them from the wolves.

I am aware that this is changing my way of thinking. I enjoy how I feel. It is a potent energy, a righteous virtue that seems completely earned. The training reassures me of my decision-making ability.

The other recruits are undergoing the same shift. During downtime we discuss guns: which we plan to buy next, what ammo our districts will provide us, and how that ammo impacts a body. We have become gun nuts almost overnight.

Before we take the peace officer assessment, we are bused to an empty high school where we take turns playing “good guys” and “bad guys.” The scenarios are designed to challenge our decision-making. Some recruits are chided for offering too many warnings, harkening back to our first day of training. Others are lectured for being too giddy with their new power. The latter are mainly people who had little experience with guns before the training; now they burst into classrooms, screaming television tropes such as “Put the fucking gun down!” In the midst of the action, I look around and think we are a group transformed, and the change feels good. I am powerful and gallant. I am a sheepdog.

Twenty of the twenty-three educators pass the assessment, and most return to schools where they carry daily. I trade in my practice rounds for hollow points, my training holster for one easily concealed beneath a suit.

The school district provides rounds designed to swell upon impact to ensure maximum harm.

My wife and I plan how we will hide the gun from our daughter. I purchase a gun safe for obvious reasons, but I also need to protect the secret. My wife, the district superintendent, and my fellow recruits from the training remain the only people who know. This secrecy, to which I had given little forethought, is uncomfortable. I regularly worry that the gun will “print” against my shirt if I lean forward or show if my shirt comes untucked.

Back at work, I walk the halls examining angles, doorways, and odd hallway configurations, just as Chris and his team instructed. When questioned by the school board, I deftly repeat the program’s military terminology, and it clearly impresses. I am high on the atmosphere.

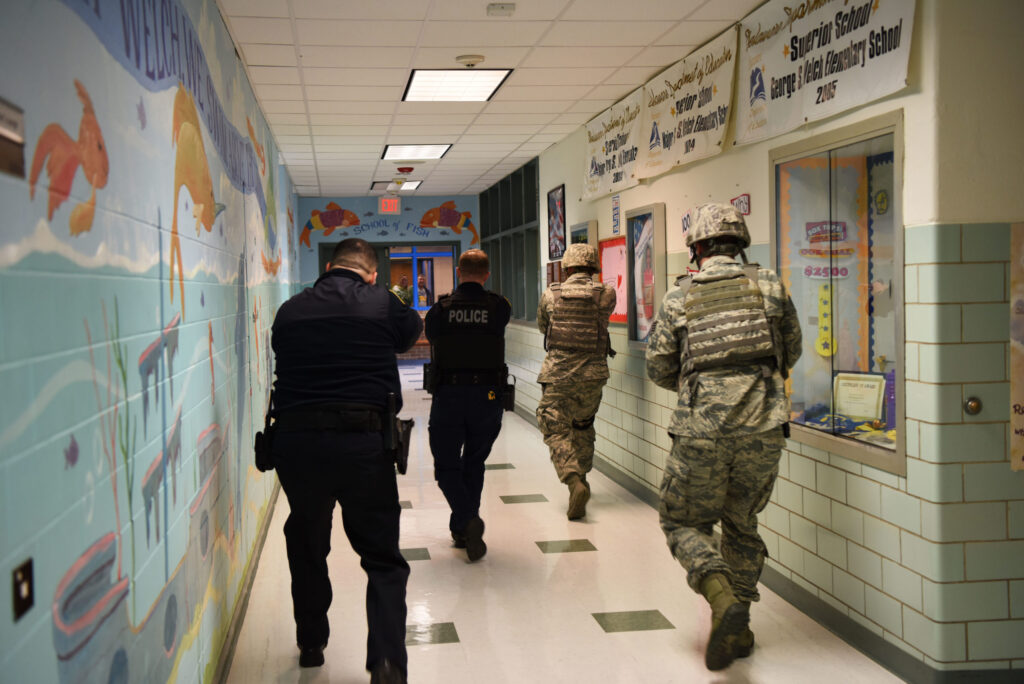

In late fall, an anonymous threat of school violence is shared on social media. It is improbable, but all threats must be handled as emergencies. The staff reacts with practiced precision, preparing students to evacuate. I begin alerting parents and working with the police.

As district staff have an emergency meeting to discuss the source of the threat, I instinctively check my Glock. It is a simple movement and not easily comprehended by onlookers: a movement to my hip, a swipe of the hands, and I am assured of its placement. Indexing, Chris called it. A term with broad meaning that includes checking if the gun is secured, loaded, available for use, and pointed in the right direction. As in a dream, I attempt to make sense of the day’s strange course.

Fortunately, the attempt by the person who made the threat to hide his identity was amateurish, and police quickly find him: Jason Moore, a junior.

“Are you sure?” I reply, giving my mind a moment to catch up.

I had visited Jason’s parents during his freshman year to discuss his attendance. They had moved to the district two years before. Sitting in their living room, they described their traveling business selling used furniture at flea markets. When they came off the road, they did their best to combine their campers by cutting doorways with a rotary saw. The result resembled a child’s crayon outline sawed in the sheet metal, tufts of insulation peeking out.

My wife and my fellow recruits from the training remain the only people who know.

I was saddened by the scene, but impressed by Jason’s resilience. He had made mistakes in junior high—nothing terrible, just poor decisions. Now he kept to himself most days. He was not an honor roll student, but he mainly steered clear of trouble. We had worked through the attendance concerns and had found a shared love of reading. He liked Tolkien-style fantasy, and I preferred literature, but our interests intersected with Ray Bradbury and Dante’s Divine Comedy. He was a respectful kid without any visible signs of aggression. He was close to making it out of the awkwardly married campers. At least, before today that was how it had seemed.

Now we sat staring at each other across the desk, the sheriff and a deputy behind him on either side.

I ask the obvious questions, and Jason casually admits to posting the threat. What’s more, when asked by the sheriff, he admits to having guns at his house, though he is adamant that he would never bring them to school.

“Why, Jason?” I finally ask, unable to hide my despair.

“They didn‘t invite me,” he mumbles, looking at his shoes.

“What? Who?”

“The others. To the party.”

Jason lays out the story, how he learned belatedly that some students in his class had planned to leave early that day for a party in the woods. Jason, who had thought they were his friends, had not been told. When Jason realized he had been left out, he gave in to anger and posted a threat, hoping to ruin the other students’ fun. It was irrational, as most teenage decisions are.

In minutes, our conversation is over, and I watch as he is handcuffed and stuffed into the back of a cruiser. The deputies try to hold back community members on the opposite sidewalk. Other policemen are already at the courthouse to obtain a warrant to search his family’s property. The married campers, I think as the cars pull away.

‘Dad,’ she starts, standing on my bed, ‘why do you carry a gun to school?’

I drive home in a devastated silence. I thought I knew Jason well, but I had never imagined him perpetrating a threat, or owning weapons. It was like something from TV, where newscasters narrate the steps leading up to a school shooting, how everyone had missed the signs. I imagine the shoot-out it could have been.

Riding through the dense countryside, I finally face the question that I had avoided from the beginning: was this right?

My decision to be armed in school had been made in the aftermath of yet another high-profile school shooting, and I had thought, “This is how I can keep my kids safe.” The training had done its work on me, too, lifting me out of my habit of cynically questioning everything. I felt reassured that of course, this is righteous. But now it was no longer a theoretical question of protecting kids at any cost. The faceless target at the shooting range, so absurd in its proportions, had a face: Jason, whom I wanted so badly to help.

I try to compose myself before entering the house. My wife hugs me just a few steps inside, knowing from social media what has happened. I whisper, “We’ll talk after I change,” and head upstairs.

Standing in the bedroom, I unlock the gun safe and begin to pull the holstered weapon from my pants when my daughter yells and clumsily pops up from behind the bed.

“Did I scare you?”

I force a smile, and she climbs over the bed as I try awkwardly to slide the gun back into my pants. Like most children, she is quick to recognize deception. Her eyes lock onto my hip, freezing me in place.

“Dad,” she starts, standing on my bed, “why do you carry a gun to school?”

I look down at her for a long moment, unable to find the words. I am a teacher, she is a student, how could I ever explain?

Note: Some names and identifying characterists have been changed.