CAMP DAVID, MD (AP)—Speaking to reporters on Saturday, President Mary Beth Cadwallader pledged to sign a landmark anti-reanimation bill into law on Tuesday after the House and Senate passed it last week. The president said that it would deliver the “final plank” of her ambitious domestic agenda as she aims to boost her party’s standing with voters about three months before the midterm elections.

The legislation—dubbed the anti-stitcher law by its supporters—would ban the medical technology known as reanimation that had been pioneered by German scientists a decade ago. The technology made possible what had only been imagined in folklore and horror novels: the reanimation of once-dead human tissue eventually resulting in over 12 million documented cases of human reanimation subjects in the United States alone. The worldwide number is uncertain, though the World Health Organization estimated that there may be more than 100 million reanimated subjects living across the globe.

Due to the recently perfected technology permitting the joining of body parts from multiple cadavers to complete a whole person, the resulting reanimated subjects became commonly known by the crude epithet “stitchers,” in reference to the joining of various body parts that requires, in part, the suturing together of flesh and muscle.

The legislation has strong backing from the country’s religious leaders who had decried animation as playing God. However, organized labor, as well as the national and numerous local chambers of commerce, lobbied the White House to veto the bill asserting that the reanimation technology benefited the sagging economy by supplying a potentially inexhaustible new source of young, healthy workers.

“This technology can’t be used to reanimate the elderly or infirm,” observed Carlos Moraga, president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “But it works like a dream to bring back otherwise healthy workers at all levels of the economy, which is good for America. And if we pull the plug on the reanimation industry, we’ll be behind the eight ball with other countries that are going full steam ahead with replenishing their workforce through reanimation.”

Anti-immigrant groups were divided on the issue because the creation of a reanimated population could eventually diminish employers’ reliance on and hunger for low-wage foreign workers. However, those same groups complained that “stitchers” were not “real Americans” and could replace native-born U.S. residents in the near future if reanimation ramped up.

In anticipating a triumphant signing ceremony at the White House, Cadwallader pointed to the bill as proof that democracy—no matter how long or untidy the process—can still deliver for American voters. The president road-tested a line she will likely repeat later this fall ahead of the midterm elections: “Real Americans and human decency won, and the special interests lost.”

I.

The man sat alone at his kitchen island. Today he needed to go into the office, but for now, he wore a white T-shirt, boxers, and slippers. The man looked down at two slices of buttered wheat toast that sat on a plate near a steaming mug of coffee. He breathed in the aroma of his breakfast and attempted to affix a word to what he felt at that moment. The bright morning sun shone through the kitchen window onto his breakfast and illuminated it like a stage where the actors stood frozen before uttering their opening lines. The man considered his breakfast.

What do I feel?

That was the question he often asked himself. The man knew he should feel something as he looked upon his daily morning meal, a meal that never changed, at least not in recent times.

What do I feel?

The man sensed something watching him. He turned his head toward the kitchen window and squinted. Ah! The neighbor’s cat, Nacho, sat at the far end of his apartment complex’s communal backyard on the low retaining wall and stared at him. Not a threat. Just a tiger-striped feline. Nacho blinked, licked its lips, and scurried away. The man turned back to his breakfast and placed both hands, palms down, on either side of his plate. The cool white quartz felt solid, secure on his skin.

Is that what I feel? Solid, secure?

The man then focused on the contours of his hands. His left hand was a full two inches longer and an inch wider than his right. And his right hand was much darker than his left. He did feel something.

I feel remorse.

Remorse that his hands were such a mismatch that people often stared and children pointed. Even when he tried to hide the vast differences between his hands by wearing gloves in the winter, people noticed—especially children, whose line of vision brought them eye-to-eye, as it were, with his mismatched appendages.

What do I feel?

Hungry. And so now this breakfast of buttered wheat toast and hot coffee served a purpose. He reached for one piece of toast and brought it to his lips. He held it there for a moment and attempted to confirm that he was indeed hungry.

Yes. I feel hungry.

The man bit into the toast and chewed.

“Is there any of that for me, guapo?”

The man turned and watched the woman walk behind the island, open one cabinet and then another until she found a coffee mug, and poured herself a cup. She turned toward the man.

“Any half-and-half left?”

Before the man could respond, the woman opened the refrigerator, scanned its contents, and emitted a pleased yes! before retrieving a small carton of half-and-half. After the woman lightened her coffee to the appropriate shade of brown, she returned the carton to the refrigerator, walked around the edge of the island, and plopped down on the stool next to the man.

“I hope you don’t mind that I used your very manly-man deodorant, guapo.”

“I don’t mind,” said the man.

“I just wish you had a hair dryer.”

The man noticed the woman’s thick, curly, black hair bounce and set free water droplets that lightly sprinkled the kitchen island and her black pantsuit. The woman smelled like the man’s shampoo mixed with the pungent scent of his Irish Spring deodorant. He liked how she smelled—his Irish Spring took on a subtler scent on her—and appreciated the woman’s glistening hair. The man thought about the woman’s wish that he had a hair dryer.

“Toast?” said the woman.

“Yes,” said the man.

“That’s your breakfast?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have something a little more Mexican?”

“Like what?”

“Pan dulce?”

“No, I don’t.”

“How about a cheese blintz? I’m happy to honor my Jewish stepfather.”

“No, I don’t have that either.”

The woman reached over and snatched the untouched piece of toast.

“Ni modo,” said the woman. “I have to watch my carbs. Healthful wheat toast it is for me.”

They sat in silence as they both crunched on their toast.

After three minutes, she said, “You know, guapo, this is the second time I’ve stayed over.”

“Yes, it is.”

“And this is the second time I’ve wondered if you’ve had something other than toast for breakfast.”

“Yes, it is.”

“And I know you’ve got a thoughtful side to you.”

“I do.”

The woman chuckled at the concise man’s response. In three quick bites, she finished eating the piece of toast and washed it down with a loud gulp of coffee.

“But you do make good coffee, guapo. That, I admit.”

“Thank you,” said the man. A small smile crept onto his freshly shaven face.

The woman stood, put her coffee mug into the sink, walked back to the man, pecked him on his left cheek.

“I’ll bring the pan dulce or maybe blintzes next time,” she said. “If there is a next time.”

“Thank you,” said the man. “I hope there is a next time.”

“Oh, you sweet talker,” said the woman. “Maybe I’ll bring both.”

“Thank you.”

“Need to grab my purse,” said the woman. “I’ve got young lawyers and law clerks to boss around, a law practice to run, corporations to sue, judges to cajole. Are you going to work today too?”

“Yes,” said the man. “After.”

“After what?”

The man thought. “After I go for a run and then make a trip to the pharmacy.”

“Got it,” said the woman. “Life’s errands and exercise wait for no one.”

“I usually run at night.”

“Well, I guess I ruined your routine last night.”

The man listened as the woman walked away from him to retrieve her purse from the man’s bedroom. The man wondered if the woman was examining his bedroom, and if so, what she thought of it in the light of day. The woman returned after a few moments and stood near the man.

“Hasta luego, my laconic hookup,” said the woman.

“Goodbye,” said the man.

The man stared at his cup of coffee as the woman stood near him. They remained in silence for several seconds listening to each other breathe. The woman eventually turned and walked to the front door. The man stared at his cup of coffee as he listened to the woman clear her throat. After a few seconds more, the woman opened the door and left. The man could discern the woman’s heels click down the walkway toward her car. The woman’s Irish Spring–infused scent lingered. The man nodded and acknowledged what he had observed before: his soap smelled different on her. He appreciated the difference and wondered what the science was behind it, if indeed there was a scientific explanation for it. Perhaps it was all his imagination, nothing more.

The man took another bite of his toast as the woman’s car started up with a vroom.

The man chewed his toast and then took another bite as he thought.

What is her name?

The man concentrated.

Her name…

The man closed his eyes for three seconds, and then his eyes popped open.

Ah! Faustina.

The man felt something, and though he was not yet certain what it was, he knew what he felt was something definable, something provoked by the fact that, if he concentrated, he could retrieve essential information when needed.

The man thought for a moment.

What do I feel?

The man smiled. He finally recognized this feeling, though he did not experience it often. But he knew that he felt it at that moment.

Pride.

The man smiled and emitted a small chuckle. But then his feeling of pride gave way to something else. Something entirely different. The man concentrated again, searching for the right word to describe what he now felt. What was it?

Shame.

The man’s face grew hot. Perspiration covered his upper lip and forehead.

Shame.

The man should have remembered Faustina’s name easily, without effort, because he had said it many times last night in bed as well as the previous Friday, their first night together. He liked the feel of her name on his tongue. Faustina. They’d met at the annual environmental law conference in Yosemite. The partners at his law firm usually didn’t let the paralegals attend, but they’d had a particularly good year, with three large settlements coming in during the spring and summer. So the partners felt generous enough to hold a lottery to see which of the firm’s five paralegals could go along with the firm’s attorneys to the annual conference. The man won the lottery by choosing the lowest number scrawled on a small brown slip of paper pulled out of a Dodgers cap. His fellow paralegals were collectively rather annoyed since the man was junior to them all. The man did not feel any remorse for being victorious because he had won purely by chance. But now the man experienced a wave of shame because he had not immediately remembered Faustina’s name. And it should have been easy. She was a partner in a boutique firm, and the firm’s name imprinted itself on his memory because he had read Faustina’s business card many times over the last week: GODÍNEZ, TSUKAMAKI & STONE. But his eyes never seemed to move beyond the large letters of the firm’s name emblazoned on the business card, otherwise Faustina’s name would have come to him easily. The man believed that he had a very visual memory. He concentrated. Which surname was hers? Think… think… think… Ah! He remembered that Faustina was the founding partner of the firm, so her surname would be first.

Faustina Godínez.

The man said the woman’s name aloud.

Faustina Godínez.

The man would never forget her name, unless he wanted to.

Faustina Godínez.

The man’s shame vanished almost as fast as it had emerged. He smiled. After a few moments, he sensed that he was being watched again. The man turned toward the window and squinted. But Nacho was nowhere to be seen. The man let out a small, almost indecipherable laugh as he returned to his breakfast of buttered toast and coffee.

And then it happened, as it often did, without warning: his mind flashed to images from his recurring nightmare from last night. The man shivered, closed his eyes, shook his head to cast out the images. He opened his eyes. What did the dream mean? Why did it come to him night after night after night? It was as if some unseen malicious power played cruel games with him. But to what purpose? What did the man ever do to anyone? But this was pure fantasy. There was no unseen power playing tricks on him. Dreams were not real. They came in different flavors, just like candy or ice cream or poison. There were daydreams, false-awaking dreams, lucid dreams, nightmares, prophetic dreams, epic dreams, mutual dreams, and many more. Perhaps the brain just working things out. Who knows? He read someplace that dreams don’t actually mean anything at all. They are only made up of electrical brain impulses that pull random thoughts and imagery from our memories. But if this was true, what memories fueled the man’s recurring nightmare? What were the building blocks for this bizarre dreamscape that invaded his nightly slumber? He had no memory of incidents that could fuel this nightmare, no experiences that would have been the foundation for what he experienced each night while he slumbered.

After a few moments, the man sensed that he was being watched again. He turned toward the window and squinted. And there sat Nacho on the retaining wall, staring directly at the man. He waved to the cat, but it did not move. The man wondered what Nacho thought. Did the man become fodder for Nacho’s dreams? Was the man nothing but a cipher to the cat, something to be studied and observed from afar and with a relentless feline gaze? Or perhaps Nacho didn’t even notice the man but stared at something else in the house that looked so much more interesting. Perhaps a tasty treat? And then the man wondered if cats even had thoughts. How can you have thoughts without words? Maybe cats were a bundle of instincts, nothing more. But perhaps meows were words, to cats at least. Meows—and don’t forget purrs and hisses—were forms of communication, weren’t they? The man turned back to his coffee and drank. It was cold. Breakfast was done. Time to move on.

TRANSCRIPT OF OVAL OFFICE MEETING, SEPT. 16, 3:35 P.M.

POTUS: Okay, so what ya got?

ESKANDARI: Um . . .

POTUS: Big picture.

ESKANDARI: Big picture, okay, overall, the polling looks to be . . .

VAN GELDEREN: Upward trend.

ESKANDARI: Upward trend, yes, overall.

LUNDGREN: [UNINTELLIGIBLE]

POTUS: How much?

LUNDGREN: One to two points, depending on which aggregate.

POTUS: One to two points?

ESKANDARI: The RealClearPolitics average has us up one point in the generic two weeks after you signed the bill.

TOMA: And FiveThirtyEight . . . Nate Silver . . . has us up two points on average.

POTUS: Fuck Nate Silver.

ESKANDARI: Right, er, CNN and the others put us someplace in between.

POTUS: That’s it?

ESKANDARI: Um . . .

POTUS: One to two points?

VAN GELDEREN: On average, depending on . . .

POTUS: We’re less than two fucking months from the midterms.

ESKANDARI: But the trend is upward . . .

POTUS: Less than two fucking months! You all said this bill would turbocharge our poll numbers.

TOMA: I don’t think we said “turbocharge . . .”

POTUS: Whatever the fuck you said. I do not want to be a goddamned lame duck with a Congress that’s going to block every motherfucking thing I do including my judicial picks. I need to keep both houses, and at least the Senate because—God forbid—Justice What-the-Fuck-His-Name goes ahead and dies on me. And then what are we going to fucking do when a new Senate that my party no longer controls gets their slimy hands on any nominee I send over? You know what’s going to happen! Nada, zilch, a big nothing because the new majority leader—who likely will be No-Chin Fuck-Face—won’t even let my nominees out of committee. You know that, I know that, my motherfucking shoes know that. So without the Senate to confirm my judges, who knows who’s going to be president after me, and there goes my goddamn legacy.

ESKANDARI: But the VP looks to be the only viable candidate after your second term ends. He’d continue your legacy.

POTUS: Ha! If I were a betting woman, it won’t be Vice President Shithead who’ll get our motherfucking party’s nomination, because voters in the primaries are stupider than fuck. If we don’t find a way to pump up our midterm poll numbers, I am royally fucked, and it will be your collective motherfucking fault! Fucked. Right. Up. My. Puckered. White. Ass.

LUNDGREN: There’s still time . . .

POTUS: There’s not a lot of fucking time.

ESKANDARI: We can hit the Sunday shows harder, and cable too. Social media, of course.

LUNDGREN: And maybe 60 Minutes. Certainly Fox News. And you did great in your first run with that Anderson Cooper interview.

POTUS: [UNINTELLIGIBLE]

VAN GELDEREN: Maybe get the vice president to do more . . .

POTUS: No, I don’t want Shithead out there on this. Did you see him on Meet the Press? A motherfucking disaster! He was sweating up a shitstorm. Looked like he was singlehandedly solving our drought the way he was gushing sweat everywhere, like Old Faithful! And he couldn’t get a goddamned word out straight, and then…

ESKANDARI: He wasn’t that bad . . .

POTUS: And then—and then—his fucking stutter broke loose and I couldn’t fucking understand a goddamned fucking word he was saying. No, Vice President Shithead stays on the sidelines on this one!

TOMA: There is an angle we haven’t pushed yet . . .

ESKANDARI: Right, the numbers look good on this . . .

POTUS: What? What angle?

VAN GELDEREN: We’ve already pushed the morality thing . . .

LUNDGREN: And the economic point . . .

POTUS: But?

ESKANDARI: We haven’t pushed hard, yet, on the law-and-order angle.

LUNDGREN: And our initial polling looks strong on that . . .

POTUS: How strong?

LUNDGREN: Kind of off the charts.

POTUS: Why the fuck have you been hiding this?

VAN GELDEREN: We didn’t have the numbers until yesterday.

ESKANDARI: Just came in last night . . .

POTUS: How do we push the law-and-order angle? I mean, it can’t be that hard, right? We have these fucking Frankensteins running amok, destroying America . . .

TOMA: You mean Frankenstein’s monsters.

POTUS: What?

TOMA: You said Frankensteins running amok, but Dr. Victor Frankenstein was—in the novel—the creator of the monster. Or maybe we should say “creature” rather than “monster”—it’s a less loaded term.

ESKANDARI: Dude, stop it . . .

TOMA: Anyway, as Professor Eileen Hunt Botting explains in her seminal book, Artificial Life After Frankenstein, the doctor and his creation were quickly conflated under the sole moniker of “Frankenstein” in the many stage adaptations that immediately followed the novel’s publication in England and France, and that conflation has continued through today.

POTUS: What the fuck?

TOMA: It’s a common mistake, you know, erroneously using the term “Frankenstein” to refer to the creature rather than his creator. So to be correct, you really meant Frankenstein’s creatures running amok destroying America—since you were using the plural—but not Frankensteins running amok.

POTUS: What the fuck do I care? I mean, really. I don’t give a flying fuck. It’s a motherfucking monster named Frankenstein, okay? That’s what normal people think.

TOMA: But . . .

ESKANDARI: Toma, shut it.

LUNDGREN: Really, Toma, let it go.

TOMA: But . . .

POTUS: What was your goddamn major in college? English?

TOMA: Well, actually, yes.

POTUS: And look how far that got you.

TOMA: [UNINTELLIGIBLE]

POTUS: Someone tell me about the havoc being caused by these violent marauding Frankensteins! There has to be something!

LUNDGREN: Yes, right . . .

ESKANDARI: There have been some stories . . .

LUNDGREN: Police reports, here and there . . .

POTUS: Like what? What stories?

TOMA: Nothing totally solid, no arrests, yet . . .

POTUS: I don’t give a shit. What kind of stories?

LUNDGREN: A few shovings . . .

POTUS: Shovings?

ESKANDARI: You, know, stitchers getting a little rough with people . . .

POTUS: Rough? How rough? This could be good shit!

LUNDGREN: Like I said, a few shovings, you know, pushing . . . physical stuff . . . reacting to people who recognize them as stitchers . . .

POTUS: Physical stuff?

TOMA: Short fuse, quick to anger, that kind of stuff.

POTUS: Broken bones? Cracked skulls?

TOMA: No, just roughed-up folks, harsh words exchanged, pretty unpleasant.

POTUS: Shit. Can you imagine if someone died?

LUNDGREN: That would be bad . . .

POTUS: Our fucking numbers would go through the fucking roof!

TOMA: But no deaths yet.

LUNDGREN: No deaths, just shovings.

POTUS: Okay, okay, we can work with this. This is good shit. Make America Safe Again, am I right? It worked for my reelection, and it can work again for the midterms. I can’t continue my fight without keeping my majorities. That’s the message!

VAN GELDEREN: We can track down stories, maybe tape some interviews.

TOMA: Maybe get some cell phone video.

POTUS: Now we’re talking . . .

LUNDGREN: I have leads on a couple of law firms thinking about suing some of the larger reanimation companies.

POTUS: But I put them out of business with the law . . .

ESKANDARI: Most of them are just repurposing to other businesses. They still have piles of cash, not to mention insurance, and new patents that spun off of the reanimation technology. So if there’s still a chance of liability from some stitcher going ballistic and hurting someone, you know these plaintiff firms will file suit and get a boatload of television and influence any potential jury pool. Our party could be on the right side of this.

POTUS: Yes . . .

TOMA: There’s a three-year statute of limitations for damages caused by any of these stitchers. There haven’t been any lawsuits up until now—which is pretty shocking, really, considering how some people feel about stitchers. There really haven’t been any real problems, until recently, with those shovings. But maybe your signing the bill has the stitchers nervous.

POTUS: So now I’m to fucking blame? I was the one who offered the only goddamn fix! Everyone else started to love these motherfucking stitchers. Community meetings, handouts, unionization, college scholarships. And those college courses! Oh my fucking God! Reanimation studies popping up in California and New Mexico and motherfucking Arizona, of all places. Everyone was falling for their sob story. Except me. I never liked them. I never trusted them. My son started dating one, but I put an end to that. It’s amazing how threatening to cut someone out of your will can bring about a little common sense, even to my loser son. So don’t lay this at my feet. I’m not to fucking blame because these stitchers are beginning to go off the rails. That’s not on me! I was the one who told the Senate and House to pass that anti-stitcher bill. And I was the one who signed it. I am not the problem. I am the solution!

ESKANDARI: No, no. Of course. We can spin it a different way. We can spin it as something that was bound to happen. And you could say I told you so.

TOMA: You know, if you play God, see what you get . . .

ESKANDARI: Law of unintended consequences . . .

POTUS: Okay, then we [UNINTELLIGIBLE]

VAN GELDEREN: Right, we can ride the law-and-order theme on the cable shows, maybe cut some commercials, and maybe we can write an op-ed for you about how you’ve made the country a safer place, and all that…

POTUS: Fucking right . . .

TOMA: This could turbocharge the midterm polls . . .

POTUS: Fucking right . . .

ESKANDARI: We can start now . . .

TOMA: We can stop work on those other spots and focus on this.

POTUS: Go now. End of fucking meeting. Turbocharge our fucking numbers. And remember…

ESKANDARI: Remember?

POTUS: Keep our stuttering Vice President Shithead away from this.

ESKANDARI: Got it.

—END OF TRANSCRIPT—

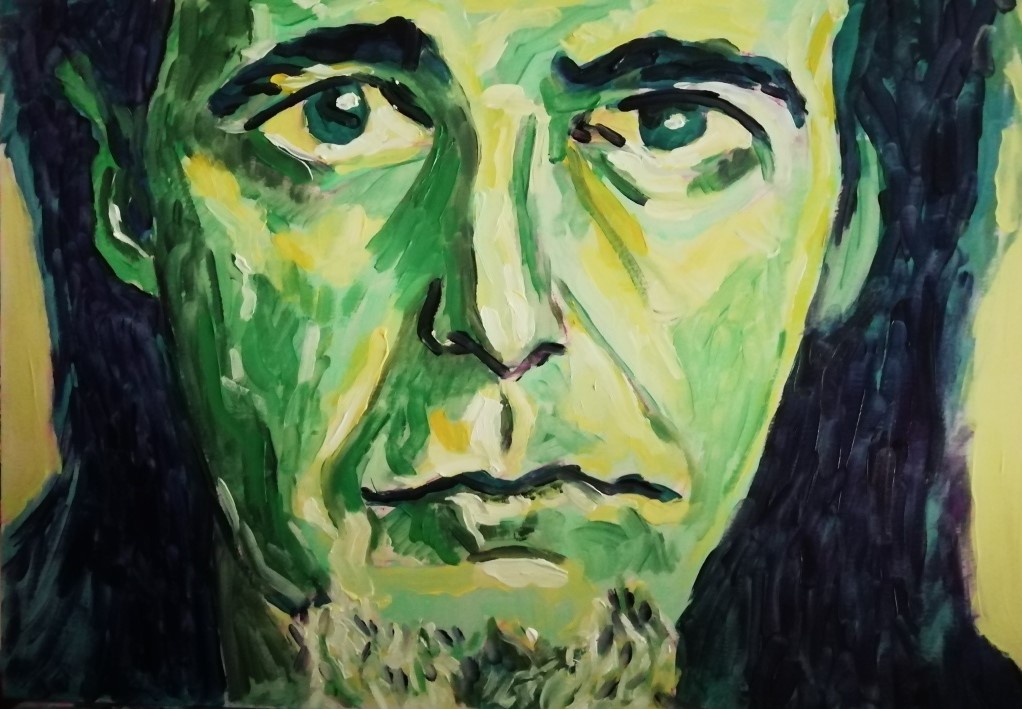

Editors’ Note: Excerpted from Chicano Frankenstein. ©2024 by Daniel A. Olivas.