PAINTERS AND POETS HAVE ALWAYS HAD EQUAL

AUTHORITY TO DARE WHATEVER THEY PLEASE.

Horace

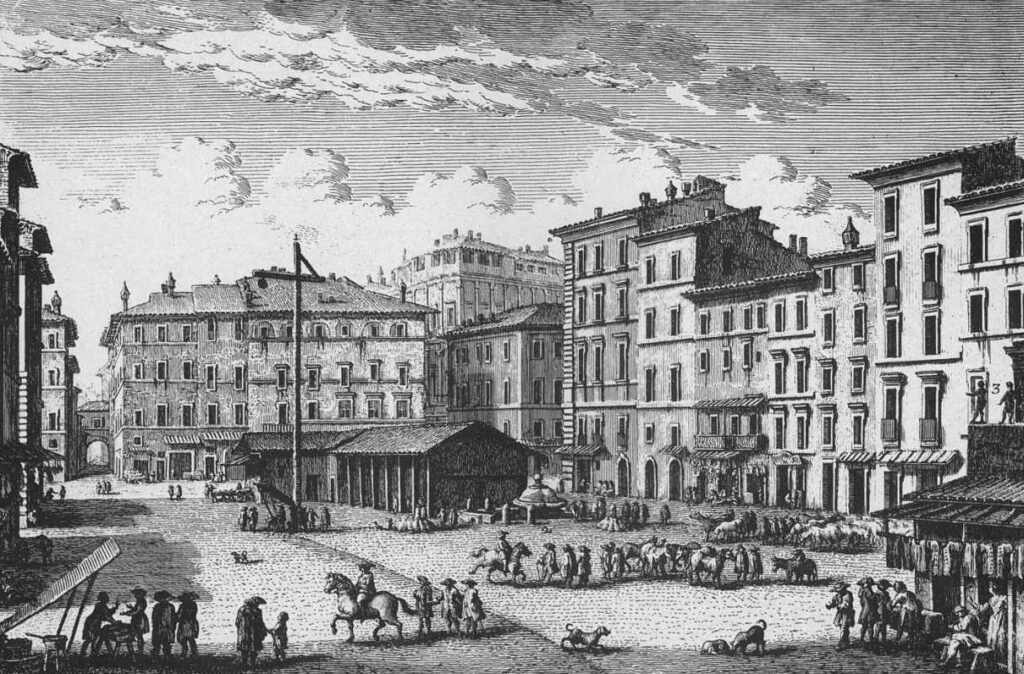

In the port city of New Giordano, whose citizens paraded in the finest fashions first worn by other people, from dialectics to slashed green sleeves, and whose clocktower, it was said, not only told time but told time what to do, there came a day when the wealthiest residents found themselves first discontented, then restive, in spite of the ships that filled the harbor with the fulfillment of their every wish. It was a pity, they murmured amongst themselves, that New Giordano had been for so long an imitator and purchaser of ideas. It was time for the city to invent a style so extraordinary that others would fall flat on their faces in awe, and afterwards envy and imitate them.

An abecedarium of aristocrats, wealthy burghers, councilors, and deans of the university gathered in the lower chamber of the town hall to discuss the matter, over goblets of wine and vinegar in which pearls had been dissolved, platters of roasted perch, and boiled turnips sculpted into castles.

The wealthiest of the merchants raised his cup to the university president. “High time that this city takes its place at the head of the world,” he said. “A whole sixty years have passed without anyone being burnt in the square. Is anywhere else more enlightened than New Giordano? Surely not.”

“The only question is how,” the university president replied.

Various cuts and attachments to shoes, hats, shirts, skirts, stockings, and overcoats were proposed, including a tail of rooster feathers pinned where a tail ought to go and an ostrich-leather boot to be called the Heir Giordano, before being dismissed as unremarkable.

The university administrators batted about clever ideas, such as revising arithmetic to make two and two equal five; punching holes through the world to prove its flatness and facilitate antipodean travel; or establishing prizes in art and literature that rewarded only those poems and paintings that gradually resolved, as if by pointillist illusion, to a detailed depiction of the artist’s navel.

“If I may venture a word,” the dean of fundraising and donor relations said. “I perceive a slight difficulty with my esteemed colleagues’ proposals. Our visiting scholars say that all of these things have been done at other universities.”

This produced much grumbling in the cherry-paneled chamber. Many pearls had to be crushed, mixed with wine, and swallowed before the atmosphere returned to one approaching conviviality.

At length one of the cannier merchants spoke. “I own three warehouses by the docks,” she said. “Today they brim with cases of duck fat and bales of silk stockings with matching yellow garters, but last month they were packed with hummingbird tongues and green blouses with slashed sleeves. Once I could no longer sell the blouses and hummingbird tongues, I had them ferried outside the harbor and dumped into the sea, to make room for the shipments of duck fat and garters. Dockside storage is far more precious than silver. I propose that the same is true of our minds, and that therefore we should empty them of past ideas.”

“We already do that,” the university president said, drumming his fingers against the oaken table. “Last week I myself ordered the rowing team to dispose of our excess copies of Marcus Aurelius.”

“Which they did, contrary to regulations, inside the harbor,” a pearl merchant said.

“They would have followed regulations. They’re on scholarships.”

“They did not,” the pearl merchant said. “Last Saturday my ships’ anchor chains were gummed up with pulp and swollen leather. My sailors lost a day to scrubbing your reactionary nonsense out of chain links. If that is the material result of your thinking, it’s high time for a revolution against the intelligentsia.”

At this, a number of the burghers looked sidelong at the university president.

“Ahem! The rowing team will be severely disciplined for it!” the president said. “I can assure you of that. I don’t suppose, by the way, that I can interest you in a text on postmodernist relativism? It is all the rage these days.”

Beneath the table, ringed hands crept toward various sharp instruments of revolution.

“Returning to my point,” the warehouse merchant said, “if ideas are discarded when no longer modish—which strikes me as sound inventory management—could we not do the same with unfashionable words?”

Knives half out of their sheathes were pushed back in as those gathered considered the merchant’s proposal.

The dean of fundraising said, “An original suggestion.”

“Indeed,” the university president said. He wiped his brow with a handkerchief. “I myself come across abstruse words in my poetry with tiresome frequency. Why, only this morning I had to learn that hetman means ataman, and that ataman means Cossack chief, and that twigs, of all things, can be verrucose!”

“I agree,” the pearl merchant said. “One of the wads of paper I cleaned off my anchor chain had the word cator—catorth—”

“Catorthoseis,” the dean of fundraising said.

“Bless you,” the first merchant said.

“That word,” the pearl merchant said, pointing at the dean. “Now what honest moneymaking enterprise needs a word like that? But it inserted itself into my anchor chain, confident as anything!”

“Very well,” said the wealthiest merchant, clasping his hands. “It is decided. We shall rid ourselves of unnecessary words to make room for more saleable goods.”

The chandeliers trembled with the fury of their applause, while the fragments of light thrown by the crystals shivered on the walls.

The curator of New Giordano’s museum of forgotten things, whose physiognotrace was seventh in the dusty sequence above the ticket-taker’s desk, was crossing the square in front of the town hall on her weekly stroll when she encountered the professors. The professors were a snarl of black worsted and poulaines, and they dragged words on leather leashes behind them, squabbling as they went. At the ends of those leashes limped the lovely long-beaked snickersnee, the chirruping, violin-winged craquelure, and a small glossary of other moth-eaten terms.

“Where are you going with those words?” the curator asked.

“To the harbor,” a green-ribboned professor said. “To drown them.”

“Why drown them?”

“They’re not needed any more.”

“Who says so?” said the curator.

“Everyone important,” another professor said, whose departmental pin was a red rosette.

“Leave them with me,” the curator said. “I’ll put them in the museum.” She stuck out her hand with such assurance that the green-ribboned professor put two leads in it before he knew what he was doing.

“Better to drown them,” the second professor said. “Old, useless things.”

“Then they’re perfect for the museum of forgotten things.”

“That mausoleum?” the green-ribboned professor said. “Hasn’t it crumbled to dust by now?”

The rosette-pinned professor sniffed. “Every doctor of literature must coin a new word before being granted her doctorate. We are swimming in new words. More are minted daily. Why fuss over these rags and tatters?”

“I like them and want them,” the curator said. “You don’t like them or want them. Seems simple enough.” She plucked the rest of the leashes out of the professors’ hands as they muttered. The gilt-faced clocktower tolled the quarter hour.

The words followed her meekly back to the museum. Once they were inside, she shut the door and set to work.

Out of specimen drawers, she took dried and tagged animals, insects, and orchids, all extinct, laying them carefully in a cedarwood chest. She lined the drawers with cotton wool to make beds for the words: scumble, holothurian, uxorious, quincunx, rencounter, ruddle, inspan, outspan, syce, pulvillus, ogive, rounceval, snickersnee, and craquelure. They blinked at her, buzzed, warbled, pawed the bedding, and settled down.

“What do I feed you?” the curator said, throwing up her hands. “Dictionaries? Primers? Books of poems?”

Ogive arched its back and purred. Syce groomed itself. Scumble brushed its feathery tail against her leg before vanishing into the depths of the museum.

“Don’t scratch anything,” the curator called after it. She went outside and puffed furiously on her meerschaum pipe. When she returned, scumble sat among the others, a gray and battered book dangling like a mouse from its jaws.

“A Report on the Cloth Industry in the Southern Hill District,” she read from the title page. “You can’t be serious.”

Black and thin-pupiled and compound eyes shone solemnly at the curator. She sighed, harrumphed, unroped a dusty velvet chair that was ordinarily out of bounds, settled into it, and began to read aloud.

Morning pooled on the floor of the museum by the time the curator awoke. The flimsy report on the cloth industry had slipped from her lap as she dozed and now lay facedown on the parquetry. Its disquisitions on sheep shearing and loom treadles had proven soporific. But ruddle was distinctly fatter and ruddier, the rest of the words a little sleeker and more content.

Scumble dropped a crumbling treatise on art at her feet. The curator picked it up and thumbed through the pages. “Chiaroscuro. Contrapposto. Silverpoint. Repoussage. Scumble. Fine, I’ll read this tonight.”

She replaced the rope across the arms of the velvet chair, pushed the treatise beneath it, put her hands on her hips, and clicked her stiff vertebrae from tail to skull. After unlocking the museum, she went about dusting rows of old helmets, old clay lamps in the shapes of fish and fools, old coins, old spoons, old evening gowns. All the while she kept a weather eye on the door, in case a lost and curious child, tourist, or student strayed in. One day, the curator hoped, a worthy successor would wander into the museum, as she herself had done several decades ago, and then she would pass on her knowledge of the museum catalogue, the finicky old stove behind the coatroom, the accessioning and selection of objects for display.

Only the mail arrived, whispering beneath the door: an onionskin letter from the curator’s daughter, who had married and fled across the mountains as quickly as she had been able.

Hello, Ma, it said, the whole family is well, wish I could visit, but you know that wreck makes me sneeze. Won’t you give it up already and embrace the future? Or at least shake hands with the present? Nail boards over the windows and come visit for a month. We’ll all be polite and you can kiss the baby.

By the time her Sylvie was ten, sticking pastilles to plate armor and putting frogs in paleolithic pots, it was clear that she would not inherit her mother’s position. Like almost everyone in New Giordano, she was allergic to history.

Dear Syl, the curator wrote, as finned, furred, and whiskered words bumped against her ankles, I have news you will not like.

At noon she went into the pocket of a room behind the coatrack and salted and fried two eggs to lace on the stove. When she sat down to eat, rounceval fixed its large eyes upon her and laid its broad paws upon her lap. She offered it a crisp brown morsel, which it sniffed but did not eat.

“Don’t be wasteful,” she said, and ate the crumb herself.

It was late afternoon, the light from the clerestory windows falling across the central hall, when a young man wearing yellow garters and clutching a yellow umbrella peered around the door.

“Is this the mineral museum?” he said.

“This is the museum of forgotten things,” the curator said.

“I’m studying to become a jeweler,” he said. “That means I must see diamonds, star sapphires, and rubies in the rough. Where’s the mineral museum?”

“On the other side of the city, and it’ll close before you get there,” the curator said. “Can I sell you a ticket? Or get you some tea?”

“Tea would be nice,” the student said, glancing around. “Um. Does it bite?”

Snickersnee was investigating his stockings and crossed garters with its scissorlike beak.

“I don’t know,” the curator said from the room behind the coatrack. She filled the kettle and added a stick to the stove. “Sure I can’t sell you a ticket?”

With two quick snips, snickersnee cut the yellow ribbons holding up the student’s stockings. The stockings slithered to his shoes.

“You can’t do that!” the student said, brandishing his umbrella at the word.

“I absolutely can,” the curator said, sticking her head out of the coatroom. “I’m the ticket-taker, cloakroom attendant, docent—oh.”

“Bad—bad—” The tip of the student’s umbrella quivered. “What is it?”

“A word,” the curator said.

“But I don’t know it.”

“It’s mostly forgotten.”

The student retrieved the remains of his garters. “What a badly behaved word,” he said. “Why keep it around?”

The kettle whistled. The curator brought out two faded porcelain teacups and a teapot on a tray, along with a stack of chocolate-covered gingersnaps. She set the tray on the ticket-taker’s desk. “I suppose I’m fond of rare and unfashionable things.”

“Those were very expensive garters.”

“What if I gave you a ticket for free?” the curator said. “As an apology.”

He bit into a gingersnap. Snickersnee clacked its beak at him.

“You can’t have it,” he said to the word, his mouth crammed with crumbs.

“I don’t think they eat,” the curator said. “I read old books to them.”

“Sounds tedious.” He swigged his tea and poured another cup. “All right, I’ll accept a ticket. And your apology.”

The curator blew dust off the box of engraved cards on the desk, inscribed the date on one of the cards, and pinned the card to the student’s shirt.

The words dogged their heels as she led the student around the museum. They were not shy about showing their beaks and teeth. He kept glancing at them, no matter what she showed him, and the curator resolved to shut them in a storage room the next time a visitor came.

“These are songs no one sings anymore,” the curator said, pulling open a drawer of black wax cylinders. She set one in a phonograph, and the voice of someone long forgotten sweetened the air. The words sat back on their haunches.

“Why does it sound so terrible?” the student said.

“The cylinder is eroded each time it’s played.”

“Some songs ought to be forgotten,” he said. “Don’t you think? They had their time. What could they say to us now?”

The curator set a zoetrope spinning. “These are dances no one knows how to dance anymore,” she said. Flickering, their movements jerky, one circle of aproned peasants wove through another.

“Quaint,” the student said. He yawned.

They went up a flight of timber stairs. The curator swept a hand across a room of frozen figures. “Here are clothes your great-grandparents might have worn about town.”

“Hmm?” The student inspected the bracelet around one mannequin’s wrist. “Cannetille and granulation around garnets and turquoise. What’s this doing here? I’ve only ever seen illustrations in books!”

“Have you found something useful?” the curator said.

“Useful! If I could discover the method, I’d be the only jeweler in New Giordano who could reproduce it.” He took a loupe out of his breast pocket and peered at the fretted wire.

“Does no one in the city know how to make this?”

“No one. We knew how, once. But it’s been forgotten.”

He spent the rest of his visit poring over the jewelry hung on the mannequins and laid in vitrines along the wall. When the clocktower pealed six times, the curator handed him his umbrella.

“The museum’s closing,” she said. “But do have one more cup of tea.”

“A bit fusty, your museum,” he said. “Lots of rubbish about. But that bracelet, those rings—extraordinary.”

“I’m sorry about your garters.”

“Never mind those—keep them.” He set his cup down, shouldered open the door, and was lost to the evening.

Something soft and insistent pressed against the curator’s leg. Scumble looked up at her, the treatise on art in its jaws.

“Ah, yes.” The curator patted scumble on its head. “Come here.”

The professors had become a plague. As often as she left the museum, the curator found them wrestling unwanted words toward the harbor. Each time, after a tongue-lashing, the curator walked off with the leashes and cages. In this way she acquired for the museum such specimens as horologe, glister, rataplan, atomy, bewray, displode, fidge, jeroboam, ochlocracy, ambry, windlestraw, negatron, mazard, madrina, speos, and carnifex. She stowed the words in closets, in the cloakroom, and in hallways, combining exhibits to make space.

She did not like to think about the many professors she must have missed, who had reached the harbor with their charges, boarded boats painted with the university seal, and rowed out past the breakwater. She did not wish to imagine the splashing and scrabbling, the bubbles that rose in a weakening stream.

A more pleasant errand, which the curator undertook monthly, was supplementing her modest stock of foxed and yellowing books from one of the less fastidious booksellers in New Giordano. The shopkeeper did not, as the merchants so wisely advised, replace unsold books every six months or so, but arranged the new on top of the old. A customer excavating the bookshop’s layers with a wooden shovel could unearth the most ancient and unpopular tomes near the floor, where they had been left to molder for generations.

Each visit, the curator bought for a negligible sum a shovelful from the bookseller’s bottom layers. In the evenings she read to the words. They always seemed plumper by morning.

One afternoon, the curator accosted a preamble of professors by the gabled produce market where boys shouted pears and apples and girls sold papers of violets and pins. High-spirited as horses, the professors tossed their liripipes and snorted at the sight of her. The curator put her fists on her hips and named their charges, one by one.

“Amphigory,” she said. “Framis. Galimatias. Grammelot. Stultiloquy. Slipslop. Taradiddle. Verbigerate. I’ll take them, thank you.”

Then she paused, pressed her face against the bars of one cage, and studied the blue-green feathers, white claws, and shining eye of the word within.

“You’ve made a mistake,” she said to the professors. “That word is not forgotten. Let it go.”

“We do not want it,” the cross-gartered dean of fundraising said, staring down his straight nose at her.

“You misbegotten fork-tongued folios,” the curator said. “There isn’t a city, a country, a spot in the world where that word is not used. It will be needed until the end of human time.”

“The world will simply have to do without it,” the dean said. “And New Giordano will lead the way.”

“Aren’t you going to pitch a fit and claim it for your museum?” another professor said, his voice acid.

“Take it, or we will drown it,” the dean of fundraising said.

The curator yanked the cage out of his hand, untied the hatch, and reached inside. In a burst of feathers, mother flew over their heads and away.

The dean clicked his tongue. “We’ll only catch it again.”

“It’s not your word to own or drown,” the curator said. “None of them are.”

The professors burst forth in expostulations.

“But we write the dictionaries!”

“The style guides!”

“The textbooks!”

“The encyclopedias!”

“We decide what is published!”

“Who else would own words?”

They jeered and sneered at the curator. Without looking at them, pausing only to wipe a wad of spit off her cheek, the curator relieved the professors of their other charges.

The caged words hopping and fluttering in her arms, the leashed words’ claws clicking and hooves clacking against the stones, the curator led the words away from the jackal laughter of the academics and toward the museum of forgotten things.

After that encounter, the curator no longer spotted the professors hauling words toward the harbor, whether on her weekly walk or while doing the marketing. Overnight, they seemed to disappear, along with yellow garters and silk stockings. The latter were promptly replaced by pouf hats with pompoms.

Everything from satin balloon hats trimmed with puffs to newsboy caps fattened with crumpled paper now graced the heads of those in New Giordano. When the curator next ventured out to the bookshop, she had to squeeze past many a promenading pouf.

“I’m looking for books with these words in them,” she said, pushing a slip across the counter. Her most recently acquired words were not easy to feed.

The bookseller squinted. “If we have them, they’ll be deep. I’ll fetch the shovel.”

Idle, the curator picked up a novel, turned the first pages, and blinked at what she saw. The next book produced the same startlement.

“What is this?” she said to the bookseller. She smoothed down pages riddled with rectangular holes. “What happened to these books?”

“You haven’t heard?” the bookseller said. “On the university’s recommendation, the city council has prohibited the use of certain words. These books were printed prior to the proclamation. In order for them to be sold in bookshops, the authors had to cut out unacceptable words. The stationary shops sold out of penknives immediately. The result is unsightly, I admit, but temporary. The prohibited words will be struck from the next printing.”

“Preposterous,” the curator said.

“No, that wasn’t one of them. I was given a list—”

The bookseller retrieved a sheet of parchment riddled with holes, each the length of some word that had been printed and then excised.

“That’s hardly informative,” the curator said.

“Well, it was only a few. Fifteen or so. Surely we didn’t need all of them. And isn’t it better to get rid of words not conducive to public virtue?”

“Which words were they?” the curator said.

The bookseller scratched her ear. “I don’t remember.”

“Of course you remember!”

The bookseller said, “I’m afraid I can’t help you. Did you wish for me to find the books you requested?”

“Yes,” the curator said. “Please don’t do anything to them.”

Nevertheless, when the paper-wrapped stack of mildewed books arrived, tiny rectangles had been sliced out of their pages. The curator stumbled more than once when trying to read from those books, for portions of inoffensive words on the verso of each page were now missing as well.

The words in the museum of forgotten things flicked their tails, fluffed their feathers, and turned round and round.

In spite of its originality and evident merit, the warehouse merchant’s plan to dispose of unwanted words failed to catch fire and spread outward from New Giordano.

“That is too bad,” the wealthiest merchant said to his secretary. “The university president must be gnawing the felt brim of his hat. He will be relieved to hear that I have prepared another option.” He opened a drawer in which lay a sheet scrawled over with script. “Send clean copies of this to all the merchants and to the university.”

It was fortuitous that the wealthiest merchant’s idea originated with him, for the law’s passage required the expenditure of unimaginable sums: to the university, to institutes of scientific research, to charitable organizations, to legislators and magistrates, to officers of the peace and several other departments of civil authority. Gold and silver were poured into the palms of anyone who could be persuaded to be flexible in their principles. This was, in the end, most of those with any authority in New Giordano. Normally a miser, the wealthiest merchant gave liberally on this occasion.

In the most ancient and noble tradition, the new law was a sumptuary law, to be inscribed above the gates of the city and fiercely enforced. It read:

All those of aristocratic birth, excellent academic pedigree, exceptional degree of income, or in a position of authority, have the right to choose for themselves the adjectives by which they are described.

To this law was attached a range of penalties, civil and criminal, from fines to imprisonment to the confiscation of property and the loss of business and professional licenses. Upon the promulgation of this law, and the simultaneous delivery of a list of those in New Giordano who qualified and a list of their selected descriptors, the city’s two newspapers obediently scrubbed all adjectives apart from the permissible ones from their pages when referring to councilors, chancellors, and academics. When the mayor was arrested for drunkenness and brawling, he had the presence of mind to insist upon being described as sober and peaceful in every report. The newspapers, loathe to bear the heavy fines for accuracy, complied. The charges against the mayor were dismissed, and the magistrate and arresting officer issued groveling apologies.

Meanwhile, one rogue reporter and thirty-four ordinary people who had not yet learned to school their tongues were arrested, tried, found guilty, fired, fined, put in the stocks, locked in the branks, and otherwise justly punished for their linguistic crimes.

Being preoccupied with finding catalogs of sufficient vintage to read to owl-eyed, two-headed horologe, which had taken to sitting on her shoulder and preening her white hair, the curator did not hear about these changes and trials. Most of the museum’s curators had lived in blithe ignorance of the present, preferring the archives of the ink-stained past. The seventh curator was no different. And so she did not notice when the currents changed.

As a tidal river does not roar its reversals, though one tide bears boats inland and the other bears them swiftly out to sea, so the fashions of New Giordano changed quietly to gold-letter jewelry and rich brocades spelling out adjectives, adjectives everywhere, with no other sign of an atavistic undercurrent that strengthened by the day. The curator saw these surface ripples and nothing more.

One afternoon, to her surprise, the dean of fundraising approached her as she walked on the square below the clocktower that ordered time itself about. He wore an enormous balloon hat with gold letters on it.

“Curator,” the dean said, giving a stiff nod.

“Dean,” the curator said. “A lovely day.”

“It must be good to get away from those relics,” the dean said. “All those potsherds. All those castoffs. All that history.”

“All those words, you mean,” the curator said. “That you had no use for.”

“Dust mites, dead ends, decrepitude—faugh! Makes a person itch just thinking about it.”

The curator lit her pipe and puffed a ring into the dean’s face. “Afraid of death?”

He sniffed. “You’ll be buried before I am. Entombed in that sarcophagus of a museum. Or is it more like a chicken coop these days?”

In truth, the curator dealt with nothing more than dry little heaps of colons, semicolons, ellipses, and commas, along with a few papery feathers and tufts of fur, all of which she swept out the door in the morning and evening. She said nothing about this.

“You were correct about one thing,” the dean said.

“And what was that?”

“The word mother should not be drowned. Olicook, malison, mugwump, certainly. We tied lead weights to those words and threw them into the sea. But mother is indeed too valuable. We auctioned it off, along with several others. The funds were a welcome addition to our endowment.”

“That word wasn’t yours to sell.”

“Nevertheless, we caught and sold it.”

“But New Giordano has many mothers.”

“You are misinformed. New Giordano has exactly one mother now.”

“Who?”

“The wealthiest of the merchants—who else? He keeps the word in a cage and the cage in a safe.”

“What will you call mothers, then? How are they to describe themselves?”

The dean shrugged. “Sows, broodmares, laying hens—whatever you like. If they wanted the word, they should have bid on it.”

He sauntered off, whistling. The letters on his hat glittered in the afternoon light, but the curator could make no sense of them.

When she returned to the museum, she found the door propped slightly ajar. She looked at the key in her hand, then at the door.

As she stepped into the cool of the museum, someone crashed into her. She fell, her limbs tangled in someone else’s limbs, and her pipe and a few bracelets and rings went skittering over the floor.

The student whose garters had previously been snipped dusted himself off, collected the bracelets and rings he had dropped, and stowed the jewelry about his person. His face was badly clawed. Yipping words nipped at him.

“Those aren’t yours,” the curator said from the floor. She touched her sore hips and discovered bruises.

“You don’t deserve them,” the student said. “No one comes here. I appreciate them. I’ll recreate the techniques. I’ll surpass every jeweler in New Giordano in skill and reputation.”

“Who’ll trust a jeweler known to be a thief?”

He nudged her side with the toe of his boot. “No one will dare to say such things.”

“And yet it will be known. If not now, another time. I am old, and I have seen a few things. Still—” She extended her hand to him. “Now, or another time, you could choose something different.”

He considered her outstretched hand. “You’re very bothersome and interfering. Are you somebody’s mother?”

“I am. And a grandmother.”

He knelt behind her, hooked his arms under hers, and lifted her to her feet. “How unfortunate for your child.”

The curator patted her rumpled hair. “Thank you. If you would be so kind as to return the rings to where they came from—”

But she found herself speaking to the empty air. The coattails of the student thief were vanishing through the open door.

Throughout the swagged and garlanded lower chamber of the town hall, immaculate waiters bore trays of slivered buffalo steaks, dropper bottles of concentrated flavors, and plates of scented foam. One of the importers’ daughters was marrying a warehouse operator’s son, a supply-chain consolidation that sparked wild joy and extravagance from both firms. As the fashion of the moment dictated, the dress was thickly embroidered with praises of the bride’s beauty and virtue, the suit likewise in boasts of strength and wealth, so that guests and reporters would know precisely which words were permitted to describe each party.

One of the not-so-wealthy merchants, a fruit dealer with a perpetual pucker, wove through the jubilant crowd to where the dean of fundraising was shaking hands and describing buildings that the university meant to build that remained unsponsored and thus unnamed.

“I am terribly sorry to hear about what happened with your son,” the fruit dealer said to the dean. “Simply aghast.”

“I can’t imagine that you’ve heard anything accurate,” said the dean, smiling so widely his molars showed, “since nothing has happened to my son.”

“Well, I heard that he stole antique jewelry from the museum of forgotten things, and knocked down the curator to do it.” The fruit dealer had been studying the dean’s face as he spoke, and at an involuntary twitch of the dean’s thin lips, he clicked his heels together and crowed. “So it’s true!”

Around them, necks craned to hear what the dean would say. The dean plucked a flute of peacock-blue liqueur from a passing tray and drank it off, then selected a sliver of steak and ate it in two neat bites. Only after wiping his fingers on a proffered cloth and shaking out his sleeves, which were spangled with eminent and respectable, did he reply.

“My son is an honest and upright young man. You would do well to remember that.”

“Yes, of course.” The fruit dealer took two peach-gold glasses and raised them to the dean. “Upright. Honest. I would never dream that he could be anything else. Please excuse me, I must congratulate the happy couple…”

He left the dean standing among the merchants and deep-pocketed baronets.

“Base slander,” the dean said. “Never mind it.”

“He’s a buzzing wasp, that melon hawker,” the pearl merchant said, “going where he’s not wanted and stinging for a lark. But I’ve never known his information to be inaccurate.”

“False it is,” the dean said, forcing a laugh. “Falser than the trick bottoms of your desk drawers, where the second ledgers are kept.”

“Of course it is a wicked fiction,” the university president said, clapping him on the back. “You shall prove it—you shall demonstrate your son’s innocence. For our donors must have full faith and trust in our institution, if they are to remember us in their legacies.”

“Certainly,” the dean said. “Most assuredly. Very shortly.”

When the fruit dealer next surveyed the room, he saw with satisfaction that the dean had gone. He sidled up to the professor of economics, who had long coveted a deanship, as the professor browsed at the trestle table.

“What do you think of my results?” the fruit dealer said.

“Compelling,” the professor said, and pressed a purse into his hand.

The officers of the peace who rapped on the museum’s door left their ceremonial pikes leaning beside the entrance.

“Are you wanting to buy tickets?” the curator asked. “Or are you here about the theft?”

“No tickets, thank you,” said the captain of the officers. “What theft do you mean?”

“Two weeks ago, seven bracelets and six rings were stolen from the museum.”

The captain stroked his mustache. “I know nothing of this.”

“I did not report the matter, since it was not important. But why have you come?”

“To arrest you on suspicion of murder.”

The words gathered around the curator bared talons and teeth.

“Murder?” the curator said.

The officers said nothing, though one flushed pink as a primrose.

“Who am I supposed to have murdered?”

The captain said, “The son of the dean.”

“The dean has a son?”

“We are here,” the youngest officer said, standing straight as a pike, “to escort you to prison before your trial.”

The curator stared, then shivered once, hard, head to toe. When the world went mad, there was no use pretending it hadn’t. “You’re arresting me for the murder of someone I have never met.”

“We are indeed arresting you. The truth of the matter shall come out in court.”

“Well then.” The curator thought. “May I take some clothes with me? A puck of tobacco? Can I bring any of these words for company?”

The officers conferred.

“You may bring one word,” the captain said.

The curator bit the knuckle of her thumb in thought. “Horologe,” she said at last. The two-headed word flew to her shoulder and gripped it tightly.

“Let me lock up the museum,” she said to the officers.

They assented.

Hands unsteady, the curator set the placard that said CLOSED beside the entrance and shut and locked the door with the short-barreled key. The streets that they escorted her down, three officers on each side, were all of a sudden unfriendly and strange, the shadows grown long and stark and sharp. A gawking face waxed gibbous at every window. The curator thought she had known the city, having been born, bred, and schooled within its precincts, but she was beginning to see that she did not and never had.

The cells beneath the town hall were damp, narrow, and largely unoccupied.

A hinged board chained to one wall served as a bed. Her stub of tallow candle made its shadow stretch and dance.

“Murder,” she said to horologe. “Me! At my age!”

With a chip of glass found in a corner of the cell, the curator began to scratch words into the limestone walls.

A horologe has many possible forms.

A horologe tells time.

New Giordano’s horologe tells time what to do.

She read the sentences aloud as she wrote.

“There,” she said, tickling the word behind each of its feathered heads. “That’s one of us fed.”

She lay down on the board as the candle guttered out, and gazed upward through thick darkness. Directly above her cell was the grand receiving room of the town hall, where the mayor and councilors regularly met, and above that, the courtroom where she would be tried. She had read too many histories to be sanguine about the prospect.

“Whoever it is,” she said. “He must be dead. And violently. I hope it wasn’t the student.”

She could hear horologe settling its feathers into finer order.

“I wonder if they think I poisoned his tea?”

Horologe gave a quiet tock.

“Such a mess,” she said, sighing. “Some misunderstanding. Surely a stranger—but who, and why, and how?”

Rolling these pebbly thoughts back and forth in her mind, the curator passed the long and sleepless night.

When the bailiffs brought the curator out of her cell, up one flight of limestone steps and another of carved wood, and into the courtroom, horologe perched on her shoulder, the noonday sun blazed through the casement windows. Everything was a dazzlement. A few minutes passed before the glare softened enough for the curator to see.

There behind the table was the magistrate in her robes. On one side of her was a cane-built cage that held a word, and on the other side of her the dean, wearing an embroidered waistcoat and his usual glower. On a stool halfway between the table and the gallery sat the student who had taken the bracelets, gold glittering in his ears. The benches in the gallery creaked beneath an assortment of professors and merchants, the portly university president among them, who watched the proceedings with avid eyes.

“You are Hettle, the seventh curator of the museum of forgotten things?” the magistrate enquired.

“I am.”

“You stand accused of murder. Are you aware of the charge?”

“So I have heard.” She rubbed her nose. “Who am I supposed to have murdered?”

“The sole son and heir of the dean of fundraising.”

“I don’t know who that is.”

“You lie,” the dean shouted, leaping from his chair. The magistrate waved him down.

“I didn’t know you had a son,” she said to the dean. “My condolences for your loss.”

“This is my son!” the dean said, gesturing toward the student. The student, twisting his fingers together, would not meet her eyes.

“This . . . he is . . . your son?” she said.

“An upright and honest young man!”

“I am on trial for murdering this man?” she said to the magistrate.

“You are.”

“But he is alive!”

The magistrate grimaced. “Legal precedent evolves swiftly,” she said. “As does language. Only a month ago, the most illustrious merchant in New Giordano stood in this courtroom, prosecuting two fishwives who had called him a wrinkled old haddock. He had the right to determine the adjectives by which he could be described, he reminded us, and one of those was unwrinkled—”

“What?” said the curator, who had not yet seen the fresh inscription above the city gates.

“—but being decidedly—having ripened with the ordinary passage of time—he—I cannot say it. At the time, however, no reasonable person would conclude—” The magistrate coughed into her sleeve. “When the difficulty was brought up to him, that most prosperous and illustrious of merchants demanded that both disputed words be brought forth, as he had an argument that would reconcile the conflicting points of law. This was done. The argument was—made. He won his case. The fishwives were beaten and released.”

“I don’t understand,” the curator said. “This young man is alive. No one has murdered him.”

The magistrate beckoned to the bailiff. He hefted the cage and set it before the court.

“Please approach the word murder, examine it, and tell us if you are not guilty of the crime.”

Murder was a loathsome toad of a word, warty, frilled, and tarry with poisonous secretions. But though its eyes glittered malice, and its barbed tail lashed, it seemed sluggish and disinclined to stir. A whiplike tongue lolled out of its mouth.

“The word appears to be ailing,” the curator said. “Other than that, murder looks the way it always has.”

At a snap from the magistrate’s fingers, the bailiff jammed his stick between murder’s broad jaws. He gestured for the curator to peer between them. Past the serried teeth that advanced in rows down the throat of the word, the curator saw the wet red gobbets and bloody clots of fur of what had once been scold.

“Who did this?” the curator said. “Who tore one word apart and fed it to another?”

The dean leaned forward. “It is the latest fashion,” he said, his voice honey and oil. “It will bring great fame and repute to New Giordano.”

Once more, the magistrate motioned him to silence.

“There is legal precedent, as I have said.”

Through the nearest casement, opened to vent the courtroom’s swelter, came a shaft of sunlight that played over the magistrate’s robes, the dean’s lettered waistcoat, and the student’s earrings. Now the curator saw that the magistrate’s robe was covered with the words honorable, admirable, and wise, that the dean’s waistcoat was embroidered with eminent, respectable, credible, and that the words in the student’s ears spelled upright and honest.

To the magistrate, the curator said, “I am innocent.” To the student, she said, “Tell them. Tell them you are alive.”

“Alive is beside the point,” the magistrate said. “But the victim may make his statement.”

The student took a deep breath. The tops of his ears flamed red. “This woman murdered me,” he said, his voice wavering. “She went on and on about how I could change for the better. That is murder, as this court can see from the word before you. She also called me a thief, when I am honest. Her words attacked me. They scratched my face and slashed my clothes.”

“Did you do these things?” the magistrate asked the curator.

“I didn’t murder anyone.”

“Did you tell him he should be better than he is? Did you call him a thief?”

“I did,” the curator said. “But that’s not murder.”

“In this court,” the magistrate said, steepling her fingers, “we use the most modern and up-to-date definitions.”

“For which New Giordano shall be known throughout the world!” the dean interjected. The professors and merchants in the gallery applauded.

“You have confessed before this court to murder, as defined by the word before us. Let us not quibble about semantics. This foulest of crimes carries the capital penalty. Given your ignorance and advanced age, however, I believe clemency to be appropriate.”

“I do not,” the dean said. The professors muttered. The magistrate ignored them.

“I hereby sentence you to destitution. All of your property shall be considered forfeit, confiscated, and turned over to the dean, to make partial restitution for the murder of his son.”

“But his son is right here!”

“Furthermore, the curatorship of the museum shall be given to my niece, who needs something to sharpen her wits and get her out of the house.”

“I do not own the museum,” the curator said, “That is one thing you cannot transfer to the dean.”

“I can, and do, declare you unfit to serve in that position,” the magistrate said. “The deed of trust establishing the museum transfers oversight of the museum to the city, should it ever lack both curator and trained replacement. I understand that you have been tardy in selecting a successor.”

The magistrate unrolled for the curator’s inspection a very old legal document, translucent, sharp-edged, and clattering with seals, and tapped her finger on the relevant clause. The shape of the sprung trap was becoming clear.

“I wish the dean much joy of my goods,” the curator said. “They consist of some clothes, a pipe, a blanket—that is all. Everything else belongs to the museum. Even the teacups. Even the tea.”

The magistrate said, “As the official under whose authority the museum falls, now that you have been dismissed from your position, I hereby surrender whatever you acquired for the museum in the course of your service into the dean’s possession, pending an examination of the catalog. This is in consideration of your straitened circumstances, which do not allow the dean proper recompense for his loss.”

The dean smiled a thin and satisfied smile. The dean’s son studied the polished leather of his shoes, the laces and eyelets, vamp and tongue.

Slowly the curator raised her face toward the magistrate.

“Everything I acquired for the museum?”

“Down to the last jot.”

Horologe flexed its claws, pricking the curator’s shoulder. She seized the word, its feathers soft in her fingers, and sprang to the nearest window. Before the bailiff could reach her, she had flung horologe through the casement.

“Fly!” she said, and horologe flew. It flapped up to the gilt face of New Giordano’s clock tower, which shone like a second sun above the square. Extending its claws, horologe unthreaded the metal nut and pried loose the ticking minute hand, then the hour. One after the other, like thunderbolts, they fell.

Then each head of horologe seized time itself in its beak. Horologe flew, and time tore.

|

Metal struck stone with discordant peals. The bailiff marched the curator back before the magistrate. “You’ve grasped the matter,” the dean said to her. “Your words are mine, to dispose of as I choose.” “What will you do with them?” the curator said. “Whatever I like,” the dean said. “Whatever glorifies New Giordano. We do have an image to maintain.” The key to the museum was confiscated. The trial was over. No one knew and no one particularly cared where the former curator went after the trial. Horologe was not seen again, though a half-hearted search was made for it, since it was now the property of the dean. On the dean’s orders, his servants chained and caged the words that the curator had collected, forty-eight in total, and removed them from the museum, along with the heaps of old books and several pieces of furniture she had acquired that the dean had no desire to keep. Since none of the museum’s words had any currency, and none of them could be usefully fed to other words, the dean had the stack of firewood meant for the museum’s stove piled up in the town square, along with the broken-up furniture and outdated books. The cages were arranged upon the heap, and the chains wound around lengths of wood and padlocked together. Fireworks were placed among the words, to give the whole thing a festive air. “Old words for old times,” the dean said, gesturing toward the pile. “New Giordano lives only for the future!” At a wave of his hand, flaming brands were laid among the books. First the books blackened and curled at their corners, and then they opened like orange roses to the air. Rockets ignited and shot upward in showers of sparks, bursting green and red and yellow overhead. The words hissed and whined, howled and yelped. The merchants and professors clapped politely at this demonstration of New Giordano’s enlightenment. The bookseller watched for a while, then returned to cutting a lacework of holes in his books, for the list of dangerous and prohibited words grew ever longer. The dean’s son had refused to watch. Finally the wood began to burn. Fur and feathers singed. Scales charred. Claws scrabbled on glowing, blackening wood. Out of the crowd ran a stooped and hooded figure. It wrenched at the bars of the cages and the tangled chains with bare hands. But the fire leapt high and hot now, and the chains were wrapped fast around the burning wood. The hem of the figure’s cloak smoldered and caught fire. Then the solitary figure blazed up like a book, fell forward among the words, struggled briefly, and was still. The magistrate’s niece spent three weeks as the curator of the museum of forgotten things before declaring herself bored to death with the place. There were no visitors, and the clothes on display never changed. The museum was shuttered, the key shut away in a drawer. The world was electrified by New Giordano’s experiments with words. Other cities began cramming words into one another with great enthusiasm, until blue also meant red and wind meant water, and everything was chaos and confusion. Before long, the practice lost its luster, as all fashions do, and became passé. It was not New Giordano but a rival port three hundred miles to the south that ingeniously proscribed adverbs. That too swept the world, including New Giordano, and then fell out of fashion, though the rules remained. Still another city insisted on using only verbs derived from adjectives, given the surpassing nobility and importance of adjectives, for as everyone knew, New Giordano had carved a famous law governing the use of adjectives above the city gates. Thus, one could redden, blush, and brighten, but not run, gasp, breathe, or cry. This rule also enjoyed a moment of popularity, and then it too lost favor. Before long, the contributions and linguistic innovations of the deans, professors, merchants, and councilors of New Giordano were forgotten, for there were few words with which people could speak about them. If those in New Giordano felt bitterness about their eclipse, they could darken and sour, but not grumble, wail, or rage. In New Giordano, for the most part, ordinary people mimed and gestured at each other to conduct the business of their days. They did not dare speak, as the wealthier and more fortunate sometimes did, for the sumptuary laws of language had grown ever harsher, the permissible words ever fewer, and no one could afford the ruinous fines. Year after year they continued in this fashion, until, in the end, language itself was emptied from the mind. No one knew anymore what the inscription over the city gate said. They knew only that the ships had stopped coming, for no one could read the bills of lading; that hardly anyone could repair the buildings that were falling into disuse, or the wagons and implements necessary for growing and transporting food; that books were no longer written or read, for almost every page was removed before they were sold, and even if they had not been, few remembered what the marks meant. Day by day, flocks of the words that survived the city’s purges flew north and east and south, or fled from the city into the hills, until none remained in New Giordano. They did not return. |

The second hand speared the paving stones, point first. The hour hand clanged, bent, and rattled onto its side. The dean’s son straightened, pulled out each of his earrings, and threw them to the floor. “No,” he said. “Call me dishonest. Call me suggestible and easily swayed. Call me guilty—I am guilty. But she did not murder me.” The magistrate stared at him. “But I have pronounced my sentence. And she has confessed to your murder.” “Say you were mistaken, then. Deceived by me. Or fallible—isn’t it human to be fallible? Tell yourself whatever you like, as long as you undo this.” “Be silent,” the dean said, gripping his son’s upper arm so tightly his own knuckles whitened. “You have said too much.” “I’ll say more.” The dean struck his son’s face. “I did this for you!” “You did this for yourself,” the student said. He addressed the magistrate again. “You let my father force one word into another because of legal precedent, so he could argue for my innocence and her guilt. But I haven’t been murdered. It was a lie to say so.” “But the word—” “Murder means what it has always meant, no matter what my father did to it.” The student stretched out his hand to the court clerk. “Give me the record. I will burn it. Let it be as though this trial never happened.” “There is no precedent—” the magistrate began. “Then I will go in the taverns and fish markets, where they know what a wrinkled haddock is, and I will tell them how you let me accuse an old woman of murdering me. I will tell them how you pronounced her guilty of my death, while I stood before you, alive and well, so you could give her position to your niece. Can you imagine what the brewers and fishwives will say about you? No—they can’t say anything. You’ve all made sure of that. But can you imagine how they’ll laugh?” Throwing his head back, he demonstrated. The dean, his face twisting with something like fear, stepped back from his son. “Give me the record,” the student said again to the clerk. The magistrate pointed at the curator. “You. I commute your sentence to exile. Take what you own and leave. Do not let me see you in this city again.” The curator left the courtroom as quickly as she could. Outside, she hurried past the hands of the clocktower, one standing, one lying on its side, and down the streets she had known for decades and no longer knew. She let herself into the locked museum, where the words leapt up to greet her, lively as flames. “We’re leaving,” she told them. She made a circuit of the museum, collecting worn tools that she supposed she could learn to use, the better-made and warmer items of clothing, an oil lantern, and an antique dogcart into whose traces she buckled inspan, outspan, and other strong and ramping words. The eastern road unspooled from the city through forested foothills, up into the mountains. By the time night fell, the curator and her words had reached the top of the first hill. New Giordano sprawled below them, bright and glorious. The curator built a small fire among the pines, smoked her pipe, and watched the city dim and darken. The words arranged themselves at her feet. “Either he’ll make it out and find us,” she said, “and I want to wait for him if that’s the case—or…” Moth after moth flew into her fire with a soft crackle and hiss. It was a long vigil. Several times she tapped the dottle from her pipe into the fire. Near midnight she saw what she had hoped never to see: a human candle burning in the square. Not long after that, flames danced up from a building that she thought might be the museum itself. They licked the clouds to orange and green. “I wish he hadn’t threatened to laugh!” she said. Then she reflected that her own unburnt hands and feet were due to his having done precisely that. “The magistrate must have dug up some cruel old law. What fathers, what sons, what days these are.” Snickersnee sent up a thin and eerie wail. Ogive, catachresis, and scumble joined in. Then all the words were howling, their voices carrying far and wide. As abruptly as they had begun, the words fell silent. Soft footsteps approached from the direction of the city. And then the student appeared in the light of her fire, a rucksack on his back. “I thought I might—” he began, hesitant before the glittering eyes of the words. “Join us?” “Apologize,” the student said. He reached into his rucksack and handed her seven bracelets and six rings. “If you’re here,” the curator said, “then who—” “My father,” the student said. The fires glowed behind him. The curator asked no further questions. In the morning, the curator, the student, and the words set off. Words would come to them when they were needed, when it was time to speak. Not so for New Giordano, which stood mute and bright in the dawn. A light wind reached through the shattered windows of the museum and stirred the heaps of cinders on the blackened floor.

|

All the while, horologe flew onward, a ribbon of time in each beak, possibility folded in its silent wings. It would fly until the hands of the clock tower of New Giordano were straightened, carried up the tower’s four hundred fifty steps, and returned to their places and paces, so that time flowed in its proper course again, and one had, at last, to choose. . .