Some of my ancestors might live just up the street. They are the people who own the black camper van with a decal brandishing the words “Irish Pride.” I pass their house on my walks, a little unsure where ethnic importance might blur into white nationalism even in the hills of Oakland, California. The sticker, a simple bloc design in green and white, joins the two potentially menacing terms in a crossword. The middle I hinges them in a calm, clover-colored Celtic cross that sends my brain thinking of meadows to flee the idea of possible racial hatred. Lightly freckled, with age-bleached red hair like my mother, the man recently waved to me from one of several cars parked on their auto-filled lot, where the couple has taken to hanging out on sunny afternoons during COVID-19.

One tribe down. Hundreds, possibly thousands, more to go.

Geneticists use the term “ancestral” to refer to the people from whom they collect DNA to serve as reference samples. But most often these samples come from plain old humans in the here and now.

The next most obvious might be the Yoruba, somewhere among the people on my dad’s side. One, who arrived from Lagos a few years ago, is a friend who lives down the hill in the flats. They refuse to choose a gender and are onto bigger issues, like devising an AI to catalog and then create 3D replicas of all of the stolen African artifacts in the British Museum.

What if my middle-aged, self-affirming Irish American neighbors had lived in Salt Lake City as children, with parents who were willing to be sampled for a 1980s French study that went on to furnish “European” DNA to scientists around the world? What if my Nigerian friend, whose father is a transnational scientist, was one of the Yoruba chosen for the International Haplotype Map project that took genetic material for a global database from family trios (mother, father, and one child) beginning in 2002?

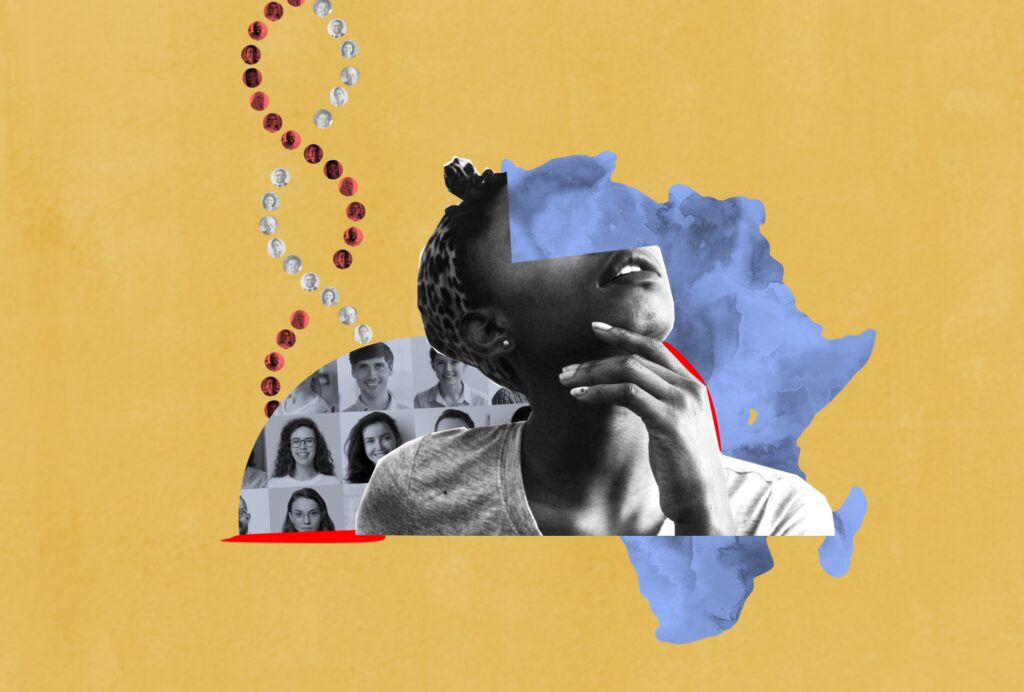

These contemporary humans could very well have been counted among the human reference samples that have now become entrenched as genetically “ancestral” for people who purchase DNA tests such as those offered by companies like Ancestry and 23andMe. Sales of these direct-to-consumer kits now make up a multibillion-dollar industry that has tested millions of people, giving them ancestry results like “63 percent Irish and 37 percent Yoruba.” In reality, the world will never know who in particular was initially sampled for most reference datasets. The names and personal information are confidential. Little more than donors’ geographical location or some aspect of an ethnic, racial, or national moniker are publicized. The point is, there is nothing inherent in who my prideful neighbors or my smart friend are as people that would exclude their DNA from the stores of biological raw material used to manufacture the modern-day product called genetic ancestry.

As such, those who have given their DNA are people, like my friend and the Irish up the street, who are intricately bound up with complex identities, passions, and existences like the rest of us. They too, in Whitman’s words, contain multitudes—that cannot be reduced to genetic sequences fixed in antiquated time. Their sequences of course contain allelic variation, along with even more similarities, when compared across the board. These too are reduced to select markers that have been culled to statistically differentiate people by geographic location (more on that later). In this process, DNA itself becomes amplified, literally and figuratively. Its new existence—phenomenally both larger and smaller than life itself—shuttles between the spaces of laboratories and everyday people’s lives via the tableaux of apps on computer and smart phone screens. “Ancestry paintings,” as one company calls the display of its autosomal DNA test results, take different forms. A common feature is that they attempt to convey the onlooker’s intimate belonging to the world’s people through colorful maps, with clear arrows indicating relation to distant lands, alongside lists of scribed identities that combine to signify the past—spatially and temporally.

Outside of labs, however, the ancestors continue on with their diverse, unpredictable, and very twenty-first-century preoccupied lives all around us.

As an anthropologist, I have spent the past two decades studying how geneticists’ beliefs and cultural ideas shape how they draw up the scientific world, both for themselves and for larger publics. One of the immediately striking aspects of autosomal genetic ancestry tests among everyday people is the emphasis on, well, ancestors.

We know that precolonial and colonial histories are full of encounters with other groups where people mixed, merged languages, and, of course, shared DNA. Yet, when cast as static reference samples, their complexity dissolves.

This is not surprising since geneticists themselves use the term “ancestral” to refer to the people from whom they collect DNA to serve as reference samples. Scientists even sometimes swap the word ancestral with “parental,” a more intimate yet more obviously personified term within a parlance of present-day family. Talking about these samples as assumed ancestors, or parents, originated as a way to frame services for potential American consumers, patients, study subjects, and curious genealogy mappers.

When I’ve given public talks, exchanged ideas with audiences at museums, lectured at universities, and conversed with friends and family about their genetic ancestry results, one thing is clear. People most often think that the DNA tests they buy are telling them something about long ago human DNA, bits of themselves directly shared with humans from another time. There is a look of disbelief, and a lot of questions that follow, when I tell them that most often their DNA is being compared to plain old humans in the here and now. With the rare exception of some Neanderthal DNA sequence variants that 23andMe uses for a specific product called the Neanderthal Ancestry Report, the DNA used in ancestry kits is not sequenced from old bones. It is not from ancient ancestors who lived on the Earth long ago. Rather, it is extracted from fellow contemporary Homo sapiens.

I call these unknown assumed ancestors the Today People to cut through the many layers of confusion that ancestry testing has created for consumers to sift through. The Today People are individuals who (withstanding the possibility of recent death) are currently busily alive in the same ways we are. They too have given their DNA to scientists. Yet most did so without being asked to pay. Many have hoped to contribute to research, others participated in studies related to their own health care, or, as has been claimed regarding Uighurs in China in one American lab, some may have been forced. The Today People are conceptually cast as past when geneticists perform a simple speech act of pronouncing them to be so. Thrown into relief, the ancestors take shape through inference and present-day scientific and human desires to explore through genes our as yet unknowable human history.

It is not possible to go back in time to sample our actual ancestors. Instead, the Today People are positioned within statistical models to stand in as proxies for them. This is not to say that inhabitants of Dublin, or Ibadan, or many other places do not share variation patterns in their DNA at different frequencies than groups elsewhere. The problem is the assumption that these patterns must have been inherited consistently from a source ancestral group long ago in a way that is more or less exclusive to the Irish or the Yoruba as they identify and are politically understood in name today. Instead, we know that the precolonial and colonial histories of the Irish, and of the people who now identify as Yoruba (but in most cases did not prior to the nineteenth century), are full of encounters with other groups where people mixed, merged languages, fused cultural practices, and, of course, shared DNA. Yet, when cast as parental, as static reference samples, their complexity—as humans living in a particular moment in history—dissolves into the shadows. They become silhouetted, absent presences known primarily for the geographical location geneticists would have them represent.

Mormons from Utah were the only samples representing Western Europe for the first two phases of the HapMap effort from 2002 to 2009. Crucially, this was a time when individual ancestry kits were first being devised for profit.

In the early 2000s, some of the earliest iterations of autosomal testing grouped ancestors in terms of continental geography: one’s ancestors were identified as being from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the pre-Columbian Americas. While subsequent tests have added nuances, such continental and sometimes national boundaries remain important features that structure how scientists differentiate ancestry groups as they seek to draw distinctions between minute fractions of specific populations’ DNA markers. In so doing, and despite framing it in terms of sophisticated genetic probability and the seemingly neutral use of geographic divisions, geneticists’ understanding of ancestry is heavily inflected by crude, yet persistent, ideas of race.

As reference datasets, the Today People are the backbone of ancestry DNA tests, and they are made to seem as though they are distant from people in places such as California, Wisconsin, or Massachusetts not only in space but also time. Yet, in reality, at least one highly researched group, consistently passed off as both distant and old, is really living right next door. Not unlike my neighbors up the road, they too claimed clear Western European roots and wore that badge in politically explicit ways.

These particular Today People reside just a few state lines away from me, in Utah. The Utah DNA was extracted from samples taken from Mormon families in Salt Lake City in the 1980s. The Mormons comprised the overwhelming majority of people used as part of a Paris-based international effort to create one of the first maps of the human genome starting in 1984. Scientists and Mormons shared the consensus that the Mormons were of Northern and Western European descent. Then they furthermore went on to become a global stand-in for “European”—specifically “Central European” (CEU)—in what would emerge as one of the most utilized genetic databases, used for myriad ancestry DNA tools, called the HapMap. Before the CEU peoples’ inclusion in the HapMap in 2002, they were initially collected as a “Caucasian” panel of reference families for the French resource that stores, collects, and distributes diverse human genetic samples, the Centre d’étude du polymorphism humain (CEPH).

Today the Utah CEPH samples have again been repurposed for the 1000 Genomes Project and the International Genome Sample Resource Database. As concerns the latter, its website features a map of the world on which color-coded dots indicate where the genotyped sample populations come from. Curiously, the 2020 map contains no European or European-descended samples from the United States. Instead, the CEPH samples are placed on the map in France (presumably to represent “Central Europe”). The corresponding genomes, however, are called “Utah residents (CEPH)” with “Northern and Western European ancestry.”

The CEU/CEPH humans are the perfect example of how genetic ancestry ideas are mashups of geography as well as assumptions about race and purity. That Mormon families were the bulk of the CEPH reference families is less surprising when one considers how their cultural emphasis on genealogy would have made them attractive to the original French team whose work was focused on “Caucasians.” Here, a group obsessed with genealogical records and willing to be sampled aligned perfectly with the interests of scientists committed to a certain vision of race and who possessed the resources to widely broadcast the samples they collected. In the CEU/CEPH label, we witness one of the only times France has enshrined the United States, “Utah,” as Old World. It is also one of the only times cosmopolitan Paris has proudly merged in an alliance of French métissage identity with Middle America. Salt Lake City as “Europe” thus became biologically entrenched, the locus of Western “Caucasian” ancestral roots, with the simple repurposing of the CEPH families for the initial HapMap and now its many afterlives.

Geneticists’ understanding of ancestry is heavily inflected by crude, yet persistent, ideas of race. Collection samples reveal miniscule representations of the genetic diversity of each continent.

The CEU Today People were the only samples representing Western Europe for the first two phases of the HapMap effort from 2002 to 2009. Crucially, this was a time when the initial ancestry testing technologies were being built in biomedical labs and in commercial sectors where individual ancestry kits were being devised for profit. 23andMe, DNA Print Genomics, Family Tree DNA, and countless others began offering DNA tracing tools to the public in the early to mid-2000s. Surely some companies had proprietary databases whose contents continue to be treated as trade secrets, yet many still relied in part on public samples that were widely shared.

Notably, the other “global populations” originally sampled for the HapMap were chosen, by contrast, from the actual geographic regions they were meant to designate historically. They are Han Chinese from Beijing (CHB), Japanese from Tokyo (JPT), and Yoruba from Ibadan (YRI). The most striking feature of this choice for many was that the HapMap was meant to be a resource that cataloged human diversity, and the groups were selected, in part, for the fact that they were European, Asian, and African. Yet they were miniscule representations of the genetic diversity of each continent. Again, a narrow conception of human diversity—sectioned along present-day conceptions of race—appeared to be a fundamental aspect of the collection. And, of course, all were people from today’s world.

If positioning our contemporaries as other, as old, as past has been the genius of the genetic genie of the ancestry testing industry, then the recurrent uses of the Utah samples for “Europe” cracks the genie’s bottle—if only a bit. Time will tell if the move for companies to rightfully be more explicit and transparent about what belies their artful phrasings of ancestry will begin to shift perceptions. Recently, in an updated primer on how 23andMe ascertains what they call “ancestry composition,” the company explained that most of their ancestral reference dataset is actually made up of contemporary people who pay to take their tests. The company writes:

Customers comprise the lion’s share of the datasets used by Ancestry Composition. When a 23andMe research participant tells us they have four grandparents all born in the same country—and the population of that country didn't experience massive migration in the last few hundred years, as happened throughout the Americas and in Australia, for example—that person becomes a candidate for inclusion in the reference data.

New Today People are growing this particular “ancestry” databases by the day. Meanwhile they are being massively repurposed for research into drug development through an exclusive agreement between 23andMe and UK-based pharmaceutical giant GSK. Their DNA, and its value, has again amplified.

For anyone interested in what these tests might provide them, it is important to keep in mind that the actual DNA taken from the reference samples are not full humans, with full genomes to be compared to testers’ entire sequences. At-home tests analyze small quantities of human biological material that companies selectively compare to ours. “Ours” meaning those of us in the “New World,” those seen to be fundamentally “mixed” in ways the ancestors—who are imagined to be more naturally pure (four grandparents born in the same country!)—are not. Direct-to-consumer testing is largely designed for the “mutts” of a modern history. This simultaneously puts consumers at the center of study while heralding a past devoid of “massive migration in the last few hundred years”—effectively suspending the reality that humans have mixed and moved throughout time.

At-home tests suspend the reality that humans have mixed and moved throughout time.

The Us are the countless who come to testing for motives too numerous to catalog. For reasons tied to the violence of this country’s colonization, many have no paper trail linking us to the varied strands of our origins. We can’t get back the lands, kin, loves, and life that European colonialism and Western imperialism ripped away, leaving palpable societal and psychological traumas that mark our actual ancestors’ descendants today. Our government has largely refused to entertain substantial Land Back requests of Native Americans, and refused to discuss the consistently tabled H.R.40, a bill to simply consider what reparations for U.S. slavery might entail. We cannot recuperate, even in these small gestures, what colonialism and racial bondage took. In light of these losses, ancestry testing itself may be a form of virtual restitution. A phantom of human remains handed back to the progeny since the much higher-value goods of countries, territory, lifeways, and lives themselves are out of the question for return.

We must ask, if many people actually desire the return of these things, then what work is commercial DNA testing actually doing? In some ways it recreates the past in a much more appealing televisual technicolor: a beautified, streamlined, open-ended cinematic landscape that can offer those dispossessed a slightly more palatable, if still haunted, human history. It evokes stories of profound human intrigue, of skin tones and facial features, of tribal names and exotic plains, of massive migrations and specifically named homelands. Any individual whose imagination is roused is invited to be part of familiar, romantic, and even tragically compelling scripts.

Humans are rightly moved by the perspectival lines and framed composition of ancestry painting. The reconstruction of one’s ancestors inspires a feeling of largeness, of humanistic possibility. Understandably. Ancestry in these terms is art as science.

As a form of inventive expression molded by human hands, DNA ancestry shows that, culturally, science too contains multitudes—just like us, or our neighbors up the street.