A Crisis Wasted: Barack Obama’s Defining Decisions

Reed Hundt

Rosetta Books, $27.50 (cloth)

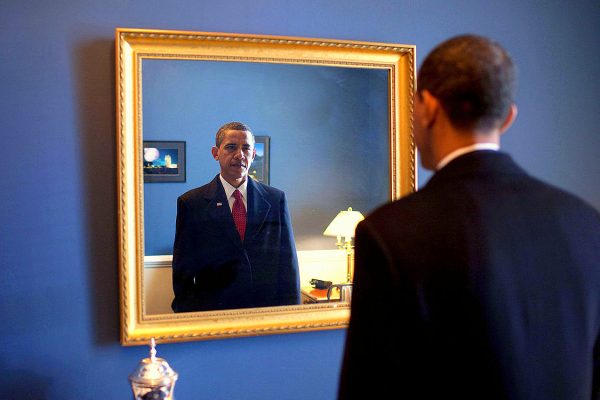

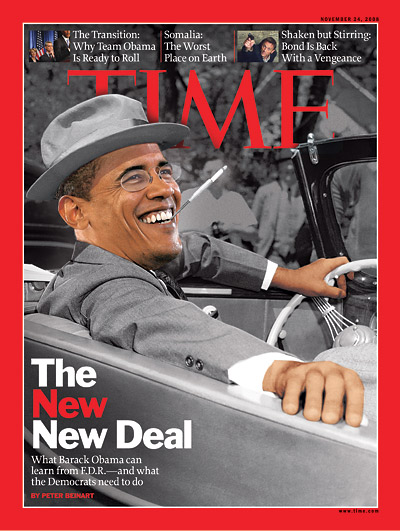

In November 2008, as a financial mudslide that had slowly been accelerating for months accumulated increasingly persuasive comparisons to the collapse that triggered the Great Depression in 1929, Time magazine ran a cover showing Barack Obama’s smiling face inserted in place of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s. The soon-to-be forty-fourth president sits in the thirty-second’s open-topped car, wearing Roosevelt’s lucky campaign hat, his grin gripping Roosevelt’s trademark long cigarette-holder. The image suggested Obama, the president-elect who promised hope and change, could follow in his Democratic predecessor’s footsteps. Roosevelt met economic crisis with massive public works programs that gave the dignity of employment to millions of Americans, and—more importantly in that era of rising fascism—helped restore their faith in the U.S. government’s ability to meet their needs.

For the better part of a half century, the Democratic Party has been in a multigenerational crisis over its past.

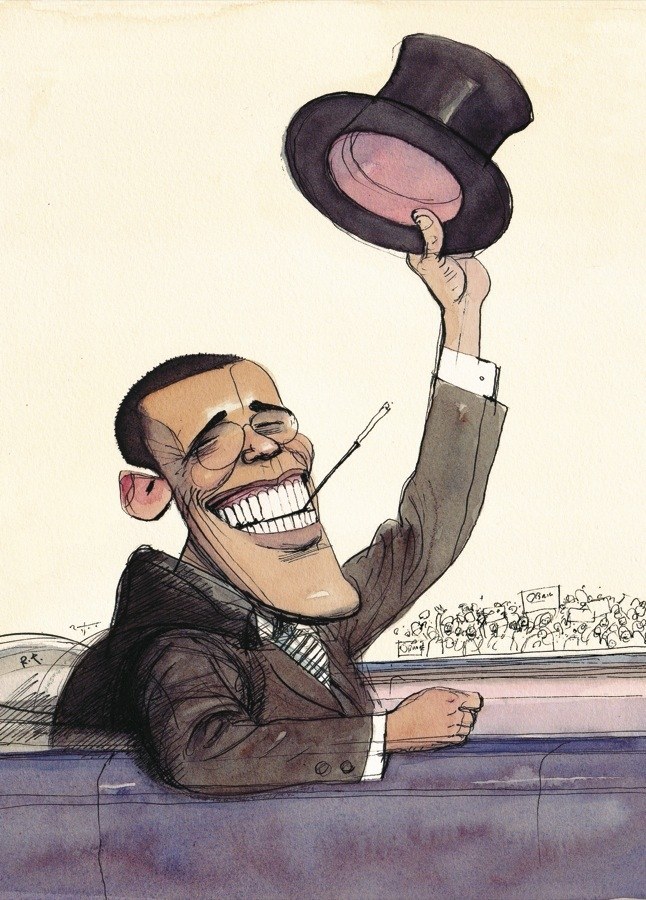

Time’s article about Obama-as-Roosevelt came a week after a New Yorker feature that sported a similar illustration but took a more tempered view. There, journalist George Packer quoted Cass Sunstein, Obama’s onetime academic colleague and sometime political advisor, describing the newly elected president as post-partisan and a “visionary minimalist”—a man little devoted to great change. This attitude, Packer noted, made Obama “distinctly un-Rooseveltian.” Before long, Packer’s more cautious view was vindicated. By 2009, when the historian William E. Leuchtenburg put out a new edition of his book on the post-1945 presidency, In the Shadow of FDR (1983), adding a chapter on Obama’s first hundred days, Leuchtenburg could already note how frequently “Obama expressed a degree of separation from the age of Roosevelt.” He even quoted the new president as saying, “My interest is finding something that works. . . . whether it’s coming from FDR or it’s coming from Ronald Reagan.”

For the better part of a half century, the Democratic Party has been in this multigenerational crisis over its past. Campaigning against Ronald Reagan in 1980, Jimmy Carter disowned the New Deal’s effort to put Wall Street in harness to Washington, declaring “we believe that we ought to get the Government’s nose out of the private enterprise of this country. We’ve deregulated . . . to make sure that we have a free enterprise system that’s competitive.” Bill Clinton fully assimilated Reaganism in 1996, saying “the era of big government is over.” And now some progressive presidential candidates—together with a base of millennial Democrats—are decrying Obama’s presidency as the last emanation of the Carter-Reagan-Clinton synthesis, a retread of neoliberalism whose weak program for recovery from the economic crisis of 2008 ensured nearly a decade of employment doldrums that aided the rise of Donald Trump.

Two representations of Obama as Roosevelt in 2008, in Time and The New Yorker respectively. Cover credits: Time, Arthur Hochstein, Lon Tweeten; The New Yorker, Richard Thompson.

Reed Hundt, once Clinton’s chair of the Federal Communications Commission and a member of Obama’s transition team, has made the progressives’ argument effectively in his new book A Crisis Wasted. Obama, Hundt believes, made decisions while still a United States senator and then as president-elect that determined the course of his presidency. In the post-election, pre-inauguration winter of 2008–2009, the ordinarily maddeningly self-assured titans of finance—the same ones who, earlier in the year, counseled government inaction in the interest of letting the market discipline its own—were suddenly, and convincingly, prophesying doom unless Washington did something dramatic to avert economic catastrophe. While many voters hoped Obama’s policies might represent a dramatic change along the lines of the New Deal, instead Obama acquiesced to emergency considerations and ideological blandishments aimed at tempering expectations and a return to “normalcy.”

The embryonic Obama administration’s adoption of Clintonesque neoliberalism was not only an inadequate response to the economic crisis, but also a failure of the new president to fulfill his campaign promises.

Obama swiftly switched from FDR redux to Clinton reborn because, Hundt points out, he sought experienced advisors to staff his administration-in-waiting, and the Democrats most accustomed to the White House were those who had served Bill Clinton. Obama named Clinton’s chief of staff, John Podesta, to head his transition team, and Podesta brought with him other Clinton appointees who thought their job now was one of restoration. As Hundt writes, “People are policy,” and the incoming Obama team wanted to bring back the policies of the 1990s and with them, the prosperity of that era. The Clinton personnel shared a more Reaganesque than Rooseveltian view, believing their success in the late twentieth century resulted from “a reduction in the size, capacity, and purpose of the public sector.” The Clinton people, following Carter, believed the New Deal had led ultimately to over-regulation and inhibition of capitalism’s great energies, and that the long boom of the 1990s owed to their getting government out of the way of business and banking, while still retaining state programs necessary to promote opportunity for the majority of Americans.

Yet, whatever one may think of the Clinton policies’ effects in the 1990s, the early twenty-first century and its economic calamities called for a profoundly different approach. The embryonic Obama administration’s adoption of Clintonesque neoliberalism was not only an inadequate response to the economic crisis. It also constituted, Hundt argues, a failure of the new president to fulfill his campaign promises. Obama could have chosen to “align himself with democracy, and then aim to help directly the great preponderance of Americans,” Hundt says, but he did not. A critical mass of voters who had chosen hope and change came to believe their president and their government did not represent or even heed them—with consequences we now know.

Hundt’s book makes an invaluable contribution to knowledge about this critical moment in 2008–2009. Because Hundt was there in Obama transition headquarters, he can recall what he himself saw and heard. He has, since then, had access to key figures who were there, too. Hundt’s notes attest to interviews with more than a dozen officials who played important parts in crafting the Democratic policy response to the crisis. At times their testimonies conflict with one another, and Hundt lets them, which probably portrays with considerable accuracy the uncertainty and disagreement that permeated the time.

The banking relief bill, for example, represents how quickly policy was made during these fraught weeks. The administration of George W. Bush had backed the bill in September of 2008 in an effort to forestall a complete collapse of the banking system; it allowed the president to spend large sums of money bailing out the financial sector. The bill’s supporters, including Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and New York Federal Reserve Bank President Timothy Geithner, did little outreach to Congress, believing the self-evident emergency should make its own case. Geithner took the view, “I just wanted Congress to pass it as fast as possible while screwing it up as little as possible.”

It is a rich and frustrating experience re-living these contentious discussions, and in relating them, Hundt shines.

This style of diplomacy initially failed to sway the House of Representatives, which rejected the bill. But Senator Obama and other backers of the bill contacted the White House to lend their support, and then lobbied members of Congress, changing enough minds to get the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act through the House, with a majority of Democrats and nearly half the Republicans lining up behind it. When Obama and his Republican opponent, John McCain, both voted for the bill from their seats in the Senate, Obama’s view that a matter of compelling national concern could garner bipartisan support was vindicated. It was a hope that carried over into the effort to craft a bill for bailing out the entire economy.

Obama, among many others, supported the bank bailouts because private lenders pump the lifeblood of a capitalist economy, and as of the fall of 2008 they had nearly stopped altogether. With the financial markets shut down, housing purchases and business starts followed; unemployment began to rise. It would take time to clear bank balance sheets and get credit circulating once more—time during which Americans would find themselves without work, drawing down savings, unable to pay their bills or ultimately to sustain shelter and food for themselves and their families. They too needed assistance.

The method of providing such aid was well known in economics and history: the government ought to spend money to make up the shortfall, thus ensuring the employment of Americans, continuing their borrowing and spending, and stimulating the slumping economy back to action. As a rule of thumb, spending 2 percent of GDP would bring down the unemployment rate by 1 percent. Economists in 2008 and early 2009 realized that, given the jobless figures, an adequate spending package would run at least $1 trillion and possibly more. Paul Krugman, the economist who had just won the Nobel Prize, explained how to do the calculations in his widely read New York Times column and blog.

Hundt’s book is at its best in demonstrating how the stimulus legislation—the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act—ended up nowhere near that number. Hundt has spoken with Larry Summers, Christina Romer, Peter Orszag, and others who played a critical role in determining the Obama pre-administration strategy for getting stimulus money out of Congress. Hundt places his readers in the room. Romer, a professor of economics from the University of California, Berkeley, who had written considerably on the Great Depression, tried mightily to get the team to support a bigger number; her own calculations suggested the stimulus should run around $1.7 trillion. Summers, the former secretary of the Treasury under Clinton and an estimable academic economist in his own right, did not dispute her substantive conclusions; he simply thought the sum too daunting to get past Congress. Orszag, also a former Clinton economic advisor and then director of the Congressional Budget Office, understood that Obama wanted to keep health insurance as a priority and was leery of ballooning deficits.

The comparison to Roosevelt still haunts the Obama team.

It is a rich and frustrating experience re-living these contentious discussions, and in relating them, Hundt shines. He lets his sources speak for themselves, differing sometimes not only on what they say should have happened, but on what they say did happen. The book here is gripping and appalling in approximately equal measure. Hundt clearly sympathizes with Romer and the arithmetic. He also plainly understands that gender was part of the reason she did not prevail. At one point in his narrative, Romer tries to make an impression by swearing in front of the president-elect. Obama uses it as an occasion to get a small laugh by calling her out, and Hundt notes that this remark put Romer off in front of the “male-dominated group.” (Hundt’s interview with Romer, like others, suggests that profanity is not alien to her.) There was a clubbiness among the men who had served in government before and who could claim the hard pragmatism of experience.

Romer was right, but somehow to be merely right was also to be basically unserious. Summers told her not to mention the figure of $1.7 trillion; he talked her down even from $1.2 trillion to something around $800 billion—which would leave unemployment somewhere around 8 percent, the planners then believed. Even with a spending bill that large, Hundt writes, the team’s “strategic goal was to end the recession, but not to guarantee robust growth and a rising standard of living.” The anti-Romer consensus carried the day, on the view that the Democrats should demonstrate fiscal responsibility: “An excessive recovery package could spook markets or the public and be counterproductive.” Congress did give them essentially what they asked for, but barely, an anonymous source tells Hundt. “Getting that 800 was very tenuous. It almost fell apart several times. Krugman and everybody are always talking crap.”

In the end, the stimulus would prove weaker than even Romer thought. Unemployment would remain over 9 percent until late in 2011. The unimpressive recovery surely contributed to the massive vote swing toward the Republicans in the 2010 midterm elections and their takeover of the House of Representatives; the slow hard march back to prosperity left many voters still bitter even in 2016. To the extent that the decision to ask for a smaller stimulus resulted from, as David Axelrod tells Hundt, “political judgments, not economic judgments,” it backfired. The Democrats gained no evident support for their demonstration of restraint in crafting a spending package, and their apparent ineptitude in fighting the recession weakened them when afterward they sought vital environmental and health care legislation.

The question, then, is what the Obama team could, or should, have done differently. They could have asked for more stimulus at the outset; even if it is true that they could not have gotten more, at least they would have been on record as believing more was necessary. Al Gore—among others—warned it would be much harder to get a second stimulus bill after a failed first one than it would be to get a big bill at the start. Romer wanted at least to manage expectations and explain how modest an $800 billion stimulus might prove. “Why can’t we actually say the truth?” she asks, at one point. Instead, the Obama team negotiated against themselves, choosing a lower number, and then saying they believed it to be sufficient.

Rather than seeking the chimera of bipartisan cooperation, Obama could have done more to preserve his campaign pledges of progressive hope and change.

Hundt also argues that by the time Obama’s team was considering a stimulus bill, they were already in a bad bargaining position. Before the election, Obama had endorsed the bank relief bill without even discussing the need for borrowers’ relief. At the time, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, Hundt says, reacted to the bank relief bill by saying, “You’ve got to be kidding,” and urging that there be “money for Main Street as well as Wall Street.” But the Bush administration, with Obama’s support, deferred the stimulus discussion and, Hundt believes, thus “snared” Obama. The bipartisanship that had so energized Obama vanished once Wall Street got its life preserver.

In the end the comparison to Roosevelt still haunts the Obama team. The economist Austan Goolsbee tells Hundt that the Obama people consciously chose not to emulate Roosevelt who, in their view, deliberately “let things get so bad” by not cooperating with outgoing president Herbert Hoover in the months before his inauguration that he arrived in the White House with a prostrate Congress willing to do any of his bidding. Roosevelt, in their view, sacrificed his countrymen to gain political advantage.

Goolsbee is here echoing Geithner and Obama himself, who have made similar remarks in their defense over the years. Their history of Roosevelt’s behavior in the bad early months of 1933 is so similar, they must have got it from a common source. In any event, Roosevelt did no such thing: Hoover did not offer cooperation to his waiting successor; rather, he demanded capitulation from him. Writing to President-elect Roosevelt, Hoover explained that his successor could combat the Depression only by forswearing inflation, budget deficits, and the massive public works programs he had promised in the campaign, thus proving himself a fiscally responsible Democrat. Only by making these pledges, Hoover said, could Roosevelt restore confidence and allow the easily upset engines of finance and business to resume their proper operations. Privately, to a fellow Republican, Hoover admitted he was not seeking any joint venture; rather, he was asking Roosevelt to trade his own agenda for Hoover’s: “I realize that if these declarations be made by the president-elect, he will have ratified the whole major program of the Republican Administration; that it means the abandonment of 90 percent of the so-called new deal.”

Roosevelt declined the Republican’s request for surrender. In thus evading the trap Hoover had laid out, Roosevelt ensured he could fulfill his campaign promises. Democracy around the world was in a bad position, Roosevelt believed, and he aimed to restore it. That was why he had told voters he would get Congress to adopt unemployment and old-age insurance, minimum wages and maximum hours laws, subsidies for farmers, and also to provide jobs on public works—not merely so that Americans would have incomes, but so they would feel their government worked for them. In building a dam or an airport or a road, in running electrical lines across a landscape to people who never had access to modern energy before, literally bringing power to the people, Washington would “help restore the close relationship with its people which is necessary to our democratic form of government.”

Rather than seeking the chimera of bipartisan cooperation, Obama could have done more to preserve his campaign pledges of progressive hope and change. In so doing, he could have done something to restore Americans’ confidence in our institutions and our democratic form of government. Alas, as Hundt notes, it was a crisis wasted.

Hundt takes up the comparison between Obama and Roosevelt in an extended riff at the end of his book. Unfortunately, he makes an error in dealing with the 1930s that he avoided in dealing with the 2000s and relies on a single—and unusually undependable—source; Hundt draws almost entirely on the memoirs of the disaffected (and Barry Goldwater–supporting) former Roosevelt aide, Raymond Moley, for his account of the New Deal. It is as if Hundt had relied exclusively on Geithner’s memoir to understand Obama’s administration. But nobody will pick up Hundt’s book for his analysis of the Roosevelt era. People should read it when considering which parts of the Democratic Party’s past should be saved, and which are best left behind.