A Whaler’s Dictionary

Dan Beachy-Quick

Milkweed Editions, $20.00 (paper)

This Nest, Swift Passerine

Dan Beachy-Quick

Tupelo Editions, $16.95 (paper)

Like so many of his peers, Dan Beachy-Quick came of age in the heyday of post- structuralism in American universities. The lessons of Derrida infuse his work with a persistent awareness of language’s intrinsic contradictions. Drawing on the basic tenets of French theory, Beachy-Quick has cultivated a poetics of intertwined reference and palimpsestic harmonies, and his two most recent books attest to the promise and pitfalls of this post-structuralist legacy.

To appreciate the pervasive—even instinctive—influence of post-structuralism, consider these passages by a few of Beachy-Quick’s contemporaries. The passages share a rhetorical structure, doubling back on themselves with a self-reflexive awareness of language’s arbitrariness:

What vicinity unconcealed itself between us . . . solicited the distance we sought to erase.

—Andrew Zawackiwhen the goal of seeking is the hidden

nothing is hidden because there is an art of signs

—Juliana SpahrI have lived, Ersatz, the confusion in my

head, the fusion that keeps confusion.

—Claudia RankineSparse, porous, scattered

any moment’s fringe epicenter is irredeemably stalling

—Noah Eli Gordon

“The face of the page both masks and reveals the author,” Beachy-Quick writes in his fourth book, A Whaler’s Dictionary (2008). His logic and even syntax recall Derrida. To draw an example almost randomly, take Derrida’s comment on Odysseus in Memoirs of the Blind: “By presenting himself as Nobody, he at once names and effaces himself.” A Whaler’s Dictionary reminds us that “a name is not enough to call back actual presence” and repeatedly demonstrates “the semiotic difficulty of the distance that occurs between any sign and any signified, the haunting arbitrariness of language’s ability to evoke and connect to the world it names.” Beachy-Quick applies a fundamental axiom of work of this kind, that “a word is elegy to what it signifies,” as Robert Hass put it 30 years ago in his oft-quoted poem “Meditation at Lagunitas.”

Beachy-Quick is adept at the classic Derridean move: identifying the simultaneity of irreconcilable contraries that, upon analysis, depend upon and collapse into one another. His book, a collection of lyrical prose meditations on Melville’s Moby-Dick, redounds with collapsed binaries and aporetic splits, contradictions that reciprocally create themselves, terms that imply and give rise to their opposites: interior/exterior, circumference/center, poison/antidote; “Queequeg is illiterate but he reads”; “the wound completes us with our imperfection.”

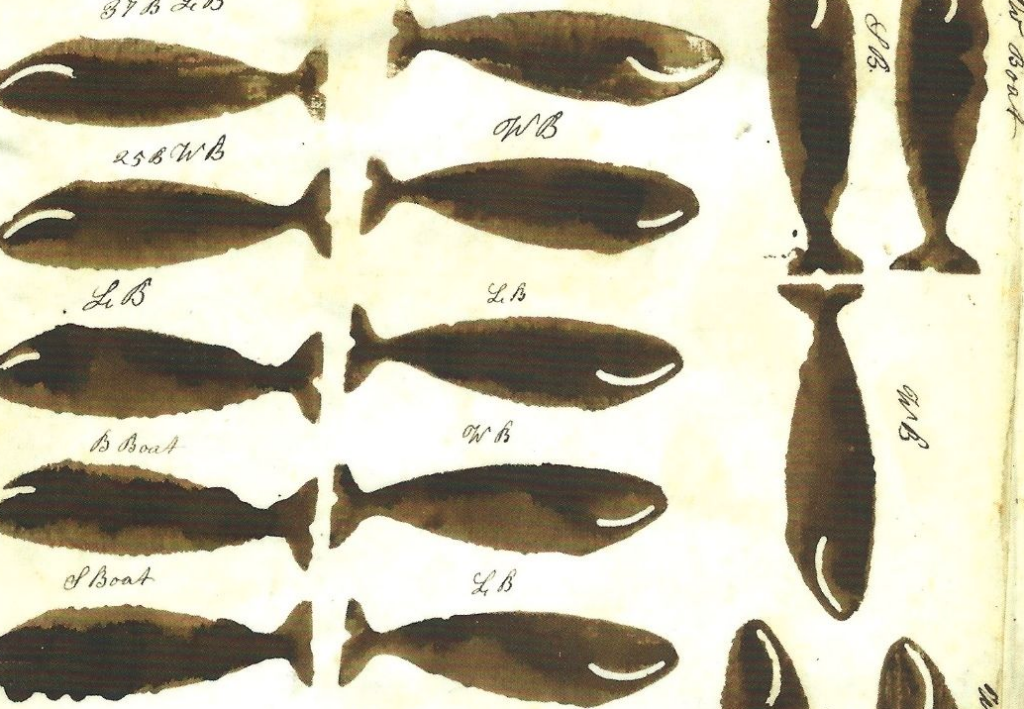

Beachy-Quick’s impetus is Ishmael’s failed cetological dictionary. Beachy-Quick takes up this scaffolding and builds an interpretive edifice of alphabetical entries, brief essays ranging from explications of Melvillean tropes to meditations on broader philosophical themes. The range is compelling: “Ambergris,” “Babel,” “Hunger,” “Line,” “Starry Archipelagoes,” “Tattoo,” “Void.” The introduction encourages the reader not to tackle the essays in order but to browse among cross-referenced entries. The result is an appealing hybrid of criticism and poetic obsession, with plenty of space devoted to explorations of the paradoxes and possibilities of language itself.

The book takes its place in a tradition of studies of the American sublime with Melville as their centerpiece. Beachy-Quick’s precursor is Charles Olson, whose 1947 Call Me Ishmael, like Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson (1985) after it, pays homage to a beloved book by creating a citational collage-text that is by turns personal, critical, and lyrical. Olson dissected Melville’s marginalia to interpret Moby-Dick through Shakespeare’s King Lear, but his opening sally identifies his preoccupation as more metaphysical than literary-historical: “I take SPACE to be the central fact to man born in America . . . . I spell it large because it comes large here. Large, and without mercy.” For Olson, Melville’s book becomes an “American Shiloh,” a sacred sanctuary, a source of “HEIGHT and CAVE, with the CROSS between.” Beachy-Quick likewise reads the American masterpiece as an ur text for spiritual quest and secular epiphany, quoting early the image of Ahab as a man with “a crucifixion in his face.” In this regard, both Beachy-Quick and Olson owe a debt to another great commentator on the Melvillean sublime, D. H. Lawrence: “If the Great White Whale sank the ship of the Great White Soul in 1851, what’s been happening ever since?” Beachy-Quick sets about offering an up-to-date answer, circling obsessively around subjects of awe and terror, exaltation and debasement, testing the sublime as the limit to the mind that proves its capacity.

Beachy-Quick adds his chapter to this discussion by wringing his material repeatedly through a Derridean sieve. Paradox as method is nothing new (William Blake had a whole lot of it going on), but Beachy-Quick points directly to post-structuralist theory as an important source for his investigations of linguistic ambivalence. He cites Derrida’s essay “Plato’s Pharmacy” and reminds us that “language makes an outside of the inside, and expresses itself in loss.” Beachy-Quick merges a wide range of allusive influences with textual insight, a maneuver he brilliantly metaphorizes as akin to the seafaring experience of the gam: “When two ships chance upon one another in the midst of the ocean’s expanse, they near each other, and, once close enough to speak across the water that separates them, information is exchanged: a gam.” Disparate voices encounter each other, as Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Martin Buber, Emmanuel Levinas, Keats, Emerson, Aristotle, Simone Weil, and others all help Beachy-Quick deconstruct Melvillean paradoxes.

That deconstruction is often first-rate, as when Beachy-Quick identifies the etymological doubleness behind Melville’s constructs: “The whale, too, is ‘antemosaic,’ a word that, like the whale, denies and doubles its own history” because it signifies both “born before Moses’ laws” and “not part of the pattern of the whole.” Beachy-Quick skillfully exposes the novel’s complex “loomings”—its interwoven image systems and its ominous fatalism—all the while modeling his own responses on that crux.

But the deconstructive move, the self-conscious trafficking in verbal paradox, becomes almost a tic. At times he lapses into doublespeak: “[The significance of Ahab’s travels] speaks to no journey but rather highlights the difficulty of staying within a single place that is no place at all.” Or tautology: “He is one and he is all. He is a single point and he is everywhere. He is living and he is dead at once.” Or the self-evident: “the men in the boats are still simultaneously hunter and hunted, pursuer and pursued.” In “Plato’s Pharmacy” Derrida explores the Egyptian deity Thoth as messenger-god and god of writing: “Every act of his is marked by this unstable ambivalence.” Beachy-Quick’s book requires a tolerance of unstable ambivalence that few readers can sustain for long. The directive to browse is merciful.

Nonetheless, the work of wading through the interpretive riffs that comprise this “thick dialectical space,” this “nexus of antinomies,” yields some resounding insight:

Etching is the art that understands that the only procedure by which to reach knowledge is to suffer the opposite.

The whale is the wall behind which the universe mockingly lingers whole.

The skin bears marks: scratches, scars, tattoos, ciphers. The skin is a continuous act of translation, a barrier to, a medium of, expression. A scar discloses history; a touch predicts.

The storm offers no transcendental harmony, no redeeming sense of our mortal inter-indebtedness—it is the indescribable strife of self moving against other self, world tumbling into world . . . , in which we are both one and at war with each other, which is to say, self-hostile, self-thunderous, self-storming.

Another brilliant stroke is the embedded epilogue: “The epilogue is hidden inside the book, unlinked to any entry but swallowed inside them all, as the snake swallows its own tail, as the whale swallows a prophet, a speaking which makes a beginning of ends.” This chapter, entitled “Unwritten Entries,” appears alphabetically near (but not at) the end and lists undiscussed themes, including “Desire,” “God,” and “Soul.” Beachy-Quick did not get to these enormities (nor to “Aristophanes,” for that matter), but the ambitious scope of the work is laid bare.

• • •

Published a few months after A Whaler’s Dictionary, Beachy-Quick’s most recent volume of poetry, This Nest, Swift Passerine (2009), underscores his reputation as an experimental yet lyrical poet, difficult yet melodic. The new book extends the metaphor for his own process that he offered in his previous collection of poems, Mulberry (2006):

The divergent strands of my poetic interests . . . [are] not divergent at all, but simply the weaving back and forth, as the head moves almost unnoticeably left to right and right to left as one reads, of those leaves I had devoured, those pages I read.

He encourages the reader to view the pages of his poetry as “a silken line, turning upon itself to create a home, for this I I am” (emphasis in original). In This Nest, Swift Passerine Beachy-Quick carries this conceit still further, both literalizing it and expanding upon its resonance as a trope for poetic form and poetic process. This Nest, Swift Passerine is a poem in three parts and nine subdivisions, linked by a series of “twinings” of themes. The book’s title and cover image direct the reader to approach the book itself as a nest—a twining of bits of language that create a seat of reading, not reference.

Framing his work in this way, Beachy-Quick relies on another post-structuralist axiom: reading is a collaborative endeavor in which writer and reader reciprocally produce a plurality of meanings. This has always been the case, whether an author liked it or not, but Beachy-Quick and many of his contemporaries seem to like it very much, and often push the principle to extremes, taking it as an aesthetic imperative or relying upon it to make meaningful even work that is otherwise committed to no meaning in particular. Not all such poets succeed in being kind enough to the reader to do justice to the procedure. Many ostensible poet-reader collaborations turn out to be exercises in reader-hating obscurity, hipper-than-thou insouciance, or faux-intimate gestures that invite vague recognition only to degenerate into outright confusion.

Beachy-Quick avoids these pitfalls with a tone of almost painful earnestness and gentle exhortation. Opening the collection is this epigraph from Emerson: “Here we find ourselves, suddenly, not in critical speculation, but in a holy place . . . .” Inviting the reader into a sacred readerly space, Beachy-Quick tries to modulate the sheer force of a deluge of reference: in addition to Wordsworth, Emerson, and more Buber and Weil, we hear from Ovid, Thoreau, Heidegger, and a slew of heavy-hitters of the English and American poetic canon, including Shakespeare, Traherne, Milton, Keats, Dickinson, Pound, and Stevens. And a little Tolstoy. And a little Empedocles. And a little Song of Songs. The syllabus is daunting but the style is mostly welcoming, a polytextual sampler laid out on the page with comfortably sized blocks of prose alternating with short-lined lyric passages and verbal arrays. Typographical devices throughout—ampersands, asterisks, vertical lines, cross-outs that show the revised text—are at times gimmicky but mostly an inventive way to package the polyphony.

What makes this cascade of high-cultural citation tolerable and even pleasing is the twining process itself—a poetics of the gerund. The syntactic motor of the book is the present participle as thing, action, and motion as form. The result is a poetic universe abuzz with “humming,” “cawing,” “echoing,” “reading,” “roaming,” “embracing,” and “thinking.” The nest-making also turns up resonant and quirkily interesting tidbits. We learn, appropriately, of the various types of spider webs (funnel, net, orb) and how they trap the spiders’ prey. We learn that the electrochemistry of the heart muscle relies on a pattern of chaotic current falling between strong beats—systole and diastole suggestive of the need for both measure and uncertainty in form. We eavesdrop on Dorothy eavesdropping on William as he works. We shudder at Milton’s harrowing account of going blind. This is postmodern reader participation of the best kind, a willingness to go with the poet as he asserts that he will “spin out of [himself] this web.” Throughout these twinings and ongoing intertwinings, Beachy-Quick enacts a beautiful tension between the web and the nest—a woven object that captures prey and a woven object that sustains and nurtures. This tension exemplifies his use of deconstructive method for strong poetic effect. He reconciles the apparent contradiction of violence and care in a twining that connects the web and nest both literally and figuratively:

Some birds snatch cobwebs from corners to help hold together their nests. Stitch dead grass to new dead grass. Stitch sere to green. Nestling hatched in silk on which the imago died. The human heart among a nest of veins.

• • •

Beachy-Quick has assimilated the terms of postmodern poetics without the corrosive irony that debilitates so many poets of his generation, and the result conveys a generosity of spirit and of utterance for which the reader can be very grateful. He is impressed by beauty, intimate in address. He has a gift for prose syntax and traditional poetic musicality, and he is not afraid to use either of them—or of sounding “literary.”

The challenge that faces this poet as he enters mid-career is how not to let the big lessons of theory—language is inherently arbitrary; reading is a participatory act—assume the status of gospel. Poets of the preceding generation often seem to approach these principles as the revelations of conversion: once, people believed in presence and immediacy and clarity, but now the enlightened must settle for a fitful embrace of tainted half-knowledges and non-hierarchical strivings to produce nodes of discourse. Presented with Beachy-Quick’s dazzling textual constellations and impeccable understanding, baby boomers are duly impressed. But Beachy-Quick’s contemporaries, who were not born again so much as born in a post-structuralist intellectual climate? Not so much. Backwashed Derrida neither recommends itself nor repulses—it is always already swilled with the dregs of this generation’s über-caffeinated intellectual breakfast.

Moreover, the whiff of piety that surrounds poetic uses of post-structuralist thought reflects the quasi-ethical imperative underlying projects of this ilk: when language purports to be transparent, it turns out to be in the service of dominant ideologies and hegemonic thinking, so resisting such language, the thinking goes, is a means to resist hegemony. When the notion of linguistic instability and contradiction is so well rehearsed that it smacks of orthodoxy, however, the efficacy or instrumentality of resistance goes unexamined and runs the risk of monotony—an aesthetic doldrums, a sameness in which the reader is becalmed. So bring on more gams: a letter, a warning, some news. Tell us something we don’t already know. And tell it through the gerunds: keep the meaning going, keep the present in process, a made-thing of motion. Gams and gerunds—this is the future of a poetry we can get behind, and that can sustain and nurture us.