“Facing a future offline was like anticipating survival in a world with no running water or electricity,” writes Tamara MacLeod. This was in the wake of FOSTA-SESTA, a 2018 law that cut off sex workers’ ability to use the Internet to screen clients for safety, advertise without a middle man, and communicate with each other. In making third-party websites liable for the content that users post, the law pushed sex work-specific platforms to shutter and others to ban sex worker users. Middle managers saw FOSTA-SESTA as a boon, an opportunity to serve as intermediaries for a workforce newly constrained in their ability to use the web to facilitate independent gig work. Sex workers had to take more risks with clients and were more vulnerable to abusive cops. Some died. More will.

The civilian—that is, the non-sex worker—left has been overwhelmingly quiet about this. This failure of solidarity has made it easier for the state to push a community of workers into ever more precarious conditions. But failed solidarities are never just that. They refract back, exposing fundamental vulnerabilities in those whose solidarities fail. When their should-be allies quietly endorse state violence, sex workers are not the only ones who lose. Potential allies also lose because sex workers, who have long known precarious conditions, are leaders in working class struggle. As state austerity and surveillance deepen, the civilian left has much to learn from people who have long organized around these conditions.

These lessons have been obscured, however, by whorephobia and the civilian left’s narrative that gig work—and thus gig workers—should be done away with rather than understood as a vanguard. This narrative argues that gig work is new and newly exploitative. Its primary goal is to bring gig workers back into full-time employee status—and the securities and relationships to the state—imagined to have once been tied to it. But sex work has always been gig work. Sex workers’ stories belie the idea that gig workers are dumbly lured by false promises of flexibility. Many sex workers seek out sex work precisely because it does not follow the rules of full-time jobs. People with disabilities, caretakers, activists and organizers, artists, and others whose lives can’t accommodate schedules bosses set might pursue sex work because it means better conditions or because they find it impossible to get and keep straight jobs. Especially for those marginalized in civilian work, writes Angela Jones, sex work is “a literal lifeline.”

This essay is featured in Imagining Global Futures.

Sex workers also turn to gigs in search of autonomy. Porn workers’ mass move from studio to self-production in their own homes reflected a struggle over workers’ control. Of course, the shift from a director’s management to a platform’s algorithmic management doesn’t deliver full autonomy. The platform exacts its own managerial force; like other gig workers, these sex workers must navigate endless workdays, low pay, and insecurity. But freedom from a boss dictating the conditions of your work can make the workday materially better. Performers of color, those with disabilities, and trans people have especially good reason to choose not to work according to others’ rules. Their needs won’t be addressed by a return to full-time jobs.

Like other gig workers, many come to sex work to avoid the managerial control of other jobs. But sex workers may find more room to maneuver, more autonomy, and higher pay than civilian gig workers. Sex work prohibitions, in physical space as in cyberspace, attempt to reign in the working-class women and queers who use sex work to achieve this kind of freedom.

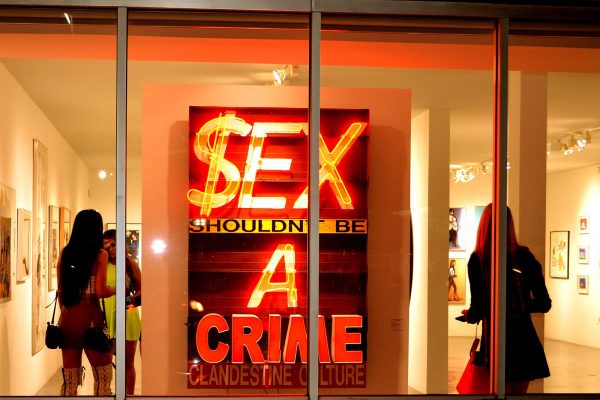

If sex workers have long sought out ways to make a living independently, they have also long faced the state’s attempts to cut this strategy off at the knees. The Internet is a kind of commons, a public space that working people can use to wrest autonomy and live otherwise. It is, for that reason, vulnerable to the capitalist state’s efforts to curb its liberatory potential. “Cyberspace can be enclosed,” writes MacLeod. She frames prohibitions against digital sex work as tools of enclosure, part of the longer story of efforts by the capitalist state to make it harder for working people to survive outside the wage relation. Enclosure manifests as sex worker criminalization but also in vagrancy laws that criminalize homelessness, zoning ordinances that prohibit street vending, and the growing privatization of public goods. Following other prison abolitionists, sex workers understand criminalization not just in terms of the laws that render survival strategies expressly illegal, but also in terms of wider projects of state and extra-state surveillance, tracking, and incursions on mobility. Today’s vanguard of sex worker organizing puts these connections front and center, opening a political horizon for those on the left ready to follow their lead.

Sex Work and Digital Enclosure

When sex workers use digital gig economies to pursue alternatives to waged work, criminalization as enclosure often moves online. Formalized with FOSTA-SESTA, efforts to enclose digital space have reached a fever pitch since. Sex workers have spent the last four years organizing against constant crisis.

Shortly after FOSTA-SESTA, shadow banning (blocking users’ content) and social media account closures amped up. This further undermined workers’ ability to keep each other safe by sharing information on screening and privacy protection, warnings about abusive clients and managers, and tips for how to work safely on one’s own. Sex workers who are also activists were doubly hit—a sex worker-led study by the Hacking//Hustling collective found that their accounts are more likely to be shut down. Banks, funds sharing apps, and payment processors, too, have barred sex worker accounts. Last summer sex workers were banned from OnlyFans—the app no longer processing payments for sex workers—only for the decision to be reversed days later. It’s no accident that enclosures take aim not just at sex workers’ ability to be naked online, but at their ability to get paid for it. Sex workers have made clear that this is fundamentally a struggle over working-class survival. The stakes are high, and they understand that “not all of them will make it.”

Now sex workers are staring down the barrel of the EARN IT act (currently advanced in the Senate), a law that would end Internet encryption and make it even harder for sex workers to use the web to make money independently and safely. Like other legal interventions sold as ways to protect kids from stranger danger, these laws both fail at their task and wreak havoc in their wake. In many instances, these laws do not make children safer, given that their abusers are most likely to be family members—fewer than .01 percent of missing kids are abducted by a stranger. And FOSTA-SESTA has resulted in just one trafficking prosecution in the four years since its passage.

Sex workers have repeatedly appealed to allies for support, organizing through Survivors Against SESTA, #STOPEARNIT, and awareness campaigns about the harms of banking discrimination. If respectable workers faced similar mass income loss, or policy interventions that made their jobs overwhelmingly less safe, the left would surely offer their support. Why don’t people who claim to care about workers’ rights support sex workers in the face of mass income loss and policy interventions that make their jobs less safe?

In part this is a story of whorephobia and bourgeois attachments to productive work and unpaid, private reproductive sex that has long created a vacuum of solidarity in the civilian left. But it also reflects the mainstream left’s inability to recognize struggles that don’t fit within the categories and demands of labor movements that were historically organized on behalf of white male workers. Gig-working sex workers don’t fit into neat class categories. Many would rather have no boss than one disciplined by collective bargaining. And like others with a long historical memory for state violence, most know the state as an antagonist, rather than as a protective force to be engaged earnestly.

Sex workers’ struggle against enclosure is resistance to proletarianization itself—to being made a waged worker. It frustrates the civilian left’s desire to maintain a coherent class category worker and thereby meet the state on its own terms. While the civilian left does, sometimes, celebrate strippers’ efforts to unionize (a priority for a small subset of the sex worker community), it stays silent when sex workers fight discriminatory policy. Whorephobia, with nostalgic attachments to conventional forms of working and organizing around work, inform this failure of solidarity, but they also cut civilian labor movements off from sex workers’ broad political vision that prioritizes the fight against digital enclosure. It won’t only be sex workers who lose in the end.

Against the “Noble Proletariat”

Speaking to sex workers’ hard-earned expertise navigating precarity and state violence, the sex worker writer Irene Silt writes:

With all this knowledge, we could have a better understanding of surveillance, racism, the police and what they do with their guns, of labor unions and their failures, of the moralism and emptiness of political parties, of reform, of the idea of respectable employment. . . . We could move past the romanticism of the working class, of the noble proletariat. But these discussions remain only between sex workers because of stigma.

Civilian left attachments to the “noble proletariat” inform a political horizon that ends with higher wages and better working conditions. This vision will only re-assert working people’s subordinate relationship to the ruling class. Its strategy aims to secure the ever-shrinking protections attached to the Fordist employee, rather than fight the enclosures that subordinate us in the first place.

Much civilian left energy in the past years has focused on getting the state to classify gig workers as employees or prevent employers from misclassifying employees as independent contractors. This is manifest now in the fights to unionize at Amazon, and these efforts have met success in the past. In 2019 labor activists in California fought for and won AB5, which formally reclassified tens of thousands of gig workers as employees. Gig workers, especially those who labor under platforms like Uber and TaskRabbit, would be (nominally) eligible for the rights and protections afforded to employees. But California gig workers’ status nonetheless remains in flux. Like most employment law in the United States, AB5 isn’t enforced, and the burden falls on individual workers to sue for compliance. This is as true for strippers and rideshare drivers alike, but sex workers already know not to expect the meager protections promised by the law.

Efforts to bring (some) gig workers nominally under state protections affords employees the ability to simultaneously demand too much and too little. Too much, because the likelihood of an enforced win is slim, and too little because even then the win wouldn’t be enough. They take New Deal labor law’s foundational racist and gendered exclusions at face value, seeking inclusion for some rather than a labor market transformation that could benefit all. New Deal-era labor law explicitly excluded domestic and farm workers (sex workers’ exclusion, while unwritten, was also foundational).

Framing gig workers’ liminal status in different ways—either as a normative and legal misclassification or as a reflection of constructed categories themselves—produces very different political work. One labor journalist warns, for instance, that the false freedom that platform capitalists offer is “threatening to destroy the U.S. labor force and turn tens of millions of workers into little more than day laborers.”

I’m reminded of an organizing meeting where I and other porn worker advocates tried to collaborate with a mainstream entertainment workers’ union on pre-AB5 policy that would have ensured wage and hour law enforcement for entertainment workers, a central concern for those laboring in creative gig economies. Porn workers, like many Hollywood crew members, get paid a fixed day rate that can stretch from two to twenty hours. One of the civilian organizers framed their fight this way: “We shouldn’t have to live south of the 10”—the I-10 interstate that bisects not only the north and south of Los Angeles, and also its whiter from its browner neighborhoods and one class of day laborers from the other.

A sex work lens reveals how efforts to reclassify some gig workers as employees seek to extend legal—and spatial—categories that were designed to benefit some at a high cost to others. Such efforts leave unquestioned the idea that benefits should be a condition of employment rather than a state-provisioned entitlement. A popular proposed third-way solution—that requires employers to contribute prorated amounts to multi-employer benefit accounts and allows workers access to portable benefits—makes this explicit. Suturing benefits to employment status, and to one’s ability and wiliness to do waged work at all, is itself a tool of enclosure. Here again, the civilian left demands too little and too much at the same time.

Contemporary sex workers aren’t the only (or first) thinkers to resist this tendency. The radical auto worker and Marxist theorist James Boggs named this critique in the 1960s with his analysis of a mainstream left whose attachments to a white, male, securely-employed proletariat limited its political horizon. Its demands sought to ossify full-time employment under Fordism, a highly particular moment in the capitalist wage relation, and one that was fading even then. Boggs looked hopefully to the “outsiders”—the mass of people who, having long labored outside the security (and the discipline) of the factory, could imagine radical alternatives. For Boggs that meant exploding the idea that work is the precondition for basic human rights: “The question of the right to a full life has to be divorced completely from the question of work.” When contemporary struggles over contractor status look romantically backward to this moment, it makes sense to return also to Boggs’ invitation.

While a few people I interviewed in my research on sex worker political thought said they wanted benefits attached to employee status, most said they’d rather not have to earn the right to a living at all. Some used queer critiques of gay marriage to highlight the difference: we can either fight to untether basic rights and protections from the legal categories set by the state or we can fight to ensure that a few people get more access to those categories. The latter strategy promises important immediate relief, but it only benefits citizens, able-bodied people, and others who can afford to play by the rules. The former hopes to rewrite those rules. The analogy helps highlight the limitations of inclusion for some even as a transitional demand—interventions such as AB5 risk shoring up the contractor/employee binary even as they also grant some people access to the latter’s status.

This isn’t to say that some sex worker organizers don’t also organize around racist and classist fault-lines. Some still advocate decriminalization based on the idea that sex work prohibitions mistakenly associate sex workers with criminality, a framing that leaves criminalization as such intact. But the vanguard of sex worker movements increasingly rejects such arguments. We see this more frequently as the public face of sex worker organizing shifts from white-led movements that frame decriminalization as a fight for privacy under the law—“get your laws off my body”—to Black, brown, and migrant-led movements that highlight working people’s struggles against enclosure—“housing not handcuffs.”

These movements organize for the lumpenproletariat more than for the “noble” one, on behalf of people who are not or do not wish to be defined by the status of worker. Sometimes these groups—the excluded and those who refuse inclusion—overlap. Broad struggles against enclosure should take priority; the fight for access to cyber space is just one.

Solidarities Against Enclosure

We see this at work when organizations such as G.L.I.T.S., No Justice No Pride, and Women with a Vision frame decriminalization within the context of struggles against racist state violence. They take aim at policing, making explicit that policing is a tool of enclosure that thrives on connections between sex workers and others harmed by the loitering laws, extractive licensing policies that promise to clean up streets, and the Internet surveillance and digital gentrification that undermine access to cyber space. Fights to decriminalize sex work name the connections between sex workers and other contingent workers, gig and other informal workers as well as those whose immigration status places their labor in liminal legal territory.

If working at the margins of the law breeds a healthy distrust of dominant institutions, it can also bring about solidarity. In their Dis/organizing Toolkit, Rachel Kuo and Lorelei Lee elaborate a model for building workers’ collectives “beyond institutions.” Produced in collaboration with the sex worker research collective Hacking//Hustling and their Informal, Criminalized, Precarious series, the toolkit looks to informal workers’ long history of executing politics outside the state. It emerges from sex and other informal workers’ “forced exclusion” from mainstream labor organizing and frustration with political collectives that assume safety in formal politics. But it also makes clear that this forced exclusion opens new possibilities.

Dis/organizing strategy emerges from “communities who have been unbanked and un-funded; excluded from communications and financial platforms, social services and social networks, and from most institutions; and unwelcome and policed in public spaces.” The toolkit draws on sex worker organizers’ expertise at organizing beyond the workplace and the categories defined by it.

Deep coalitions become possible when organizers start from this place. The migrant massage worker collective Red Canary Song, for instance, organizes alongside street vendors, day laborers, domestic workers, and restaurant delivery workers to contest the intersecting forms of state violence that make workers’ lives precarious. Working with groups such as the Street Vendor Project, the collective highlights that sex workers and street vendors understand how lawmakers’ promises to “clean up the streets” actually create harm. They know that struggles over public space—physical and digital—are fundamentally struggles over the right to make a living.

Red Canary Song’s community-based research on migrant massage licensure, written in collaboration with migrant sex worker organizers from across the United States and Canada, frames the issue squarely in terms of the “racialized policing of poverty.” It’s not an accident, the report points out, that racialized policing intensifies when social safety nets shrink. The collective’s political demands gesture to the political horizon that opens up when organizers think beyond the workplace and its categories. Alongside demands to repeal sex work-specific prohibitions, they demand that the state ease work permit restrictions for all migrant workers, reallocate anti-trafficking funds to legal and social services for migrant workers, and abolish tiered immigration systems. In approaching the state as a known antagonist (rather than earnestly, as most appeals for New Deal-style protections do), the collective refuses the civilian-left narrative that resistance to regulation is a libertarian conceit.

Sex worker organizing shows the possibilities that open if we begin from the understanding that gig work is already a kind of day labor. From here we can begin to see gig workers’ liminal legal status as a kind of undocumentation, a precarious position manufactured by the capitalist state. Then we can start imagining political demands beyond the categories of employee and citizen.

Sex workers are a “test population,” as sex worker and tech-justice activist Bardot Smith puts it. The state tests novel forms of criminalization on this community and develops new technologies of surveillance there. Silences and failed solidarities on the mainstream left only further enable this. But access to the open Internet will be crucial for the platform cooperatives that scholars and activists advocate as the new horizon for gig-workers. It will be crucial for defending the right to abortion, which is fundamentally a labor justice concern. As the history of policing’s role in labor discipline suggests, labor activism in cyber space is as vulnerable to capitalist state violence as its equivalents in physical space are and were. From the vantage point of sex work, organizers can see gig precarity as one of many products of state violence. The left won’t win if sex workers don’t too.