Going into Michael Almereyda’s new Hamlet, Bardolaters had every reason to fear the worst. The experimental filmmaker was best known for Nadja, a black and white vampire film that featured Pixelvision–video produced by a $45 Fisher-Price PXL 2000 toy camera. Almereyda, who wrote and directed this low-budget film, also used flashbacks of Bela Lugosi footage and worked in a sub-text about HIV infection. Like much avant-garde filmmaking, Najda was more style than substance–not a promising preface to Shakespeare.

Thumbing his nose at traditionalists, Almereyda announced that his Denmark was to be a multinational corporation headquartered in New York City instead of a kingdom, and Elsinore a ritzy apartment hotel instead of a palace. A Hamlet for "Generation Next," the play would run less than two hours. The official Miramax Web site proclaimed, "The President of the Denmark Corporation is dead, and already his wife is remarried to the man suspected of the murder. Nobody is more troubled than her son Hamlet (Ethan Hawke). Now, after this hostile takeover, trust is impossible, passion is on the rise and revenge is in the air." Sounds like the Madison Avenue version of the greatest play in the English language. Surely this could only mean that the seven magnificent soliloquies had been butchered and the development of all of the play’s complex characters had been compromised. There was no way that Hamlet could be the moralizing, psychologizing, politicizing, improvising, existentialist actor-prince in this bowdlerizing version.

Every character in Hamlet is in some way deeply ambiguous and each actor’s and director’s interpretation of a part can tilt the moral adventure of the play. Is Queen Gertrude an innocent dupe, or had she already committed adultery with Claudius before he killed her husband? The Ghost, in his speech to Hamlet, describes her as won over to that "shameful lust." Has Ophelia already had an affair with Hamlet before her brother and father warn her to guard her virginity? Shakespeare filled her mad scene with bawdy double entendres. Is Polonius a shrewd courtier who rightly has the ear of King Claudius, or is he the "prating fool" that Hamlet proclaims him? John Updike’s recent Hamlet prequel imagines Polonius as a co-conspirator in the adulterous regicidal plot. Do Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deserve their terrible fate? Tom Stoppard wrote an entire play pursuing that question. And what about Hamlet? Has he merely put on an "antic disposition," as he warns his friend Horatio in the first act? Or has he gone mad, as he explains himself to Laertes in the last act? Volumes have been devoted to Hamlet’s possible diagnoses.

The answers to these questions of character shape our understanding of the play, and there are many other ambiguities of the text that every director and his actors will struggle to resolve, knowing that Bardolaters will sit in judgment of every nuance. The late John Gielgud, who reputedly was the best Hamlet of his generation, wryly observed that in no other role does one hear members of the audience loudly whispering your lines.

How to interpret those sometimes baffling lines has been the challenge to all the great actors who have had the courage to attempt that unforgettable poetry. And there is no certain or definitive rendition. Hamlet’s character and his ideas are inescapably complex and every simplification seems an oversimplification–particularly on film, where the actor’s interpretation can be scrutinized again and again. Even Olivier’s 1948 Oscar-winning performance seems, in retrospect, to have short shrifted the other characters and reduced Hamlet to his Oedipus complex and Sir Laurence’s narcissism. And that was Olivier. What cartoon characters could one expect from a director who had cut the more than four hour play down to 112 minutes?

Almereyda "Let the great axe fall" on the entire dynastic structure of the play. The question of whether Claudius has "popped in" to the line of royal secession by marrying Gertrude and thus prevented Hamlet from becoming king is lopped off. Hamlet is no longer a prince, and the play within the play is also no longer the "thing that catches the conscience of the king." Henry James noted that Shakespeare the artist is everywhere in his plays, but Shakespeare the man is nowhere in them. My fantasy has always been that Hamlet is the character who comes closest to being the person Shakespeare was. And Almereyda has taken the liberty of making this Hamlet in his own image–a student filmmaker whose "mousetrap" is a homemade video instead of a play. That radical translation not only allows the director to make the play his own, if you can stomach this colossal conceit; it is a marvelously apt strategy for this hi-tech, New York Hamlet. He enters the king’s court, now a corporate press conference, with a video device in each hand; facing down the world with his camera instead of his mordant wit. The Ghost, first glimpsed on the Elsinore Hotel’s security monitors, disappears into a "Pepsi One" dispenser. Every scene contains fax machines, video displays, Polaroid cameras, voice mail, and, of course, the PXL 2000. One critic nailed the film as the "Radio Shack Hamlet." But taken "all for all" it works brilliantly.

Almereyda, as it turns out, is a serious and gifted filmmaker. Dig into his resume and you discover that he wrote an original screenplay for Wim Wenders. He based his own first film on the Lermontov novel A Hero of Our Time, and his stylish vampire film was produced by David Lynch. Lynch considers him the best of the new wave of directors, and judging by his Hamlet, Lynch may be right. His intelligence makes this Hamlet sparkle. His idea was to make a film that would be an echo chamber for a text that is alive in the minds of his audience.

To prepare himself for his project, Almereyda went through film archives and studied every Hamlet film that had ever been produced, including the silent versions. He read and reread the play as well as some of the literary criticism. He appropriated everything he liked from earlier performances and then steeped it all in his own quirky irony and the grainy, magnified, black-and-white images of his trademark Pixelvision. Almereyda threw himself, his wit, and his sly humor into the project and reinvented the play as an American film for the 21st century. But despite all the novelty, this is not for beginners. This is Hamlet for "insiders," people who really know and love the play and still want to be surprised by its possibilities. Orthodox Bardolaters with settled expectations will find much to lament. The play within the play is lost, and with it Hamlet’s wonderful directions to the players, "Suit the action to the word, the word to the action." Many other favorite lines and scenes are gone. Still, those who welcome radical invention will taste Shakespeare’s wine in Almereyda’s new bottles.

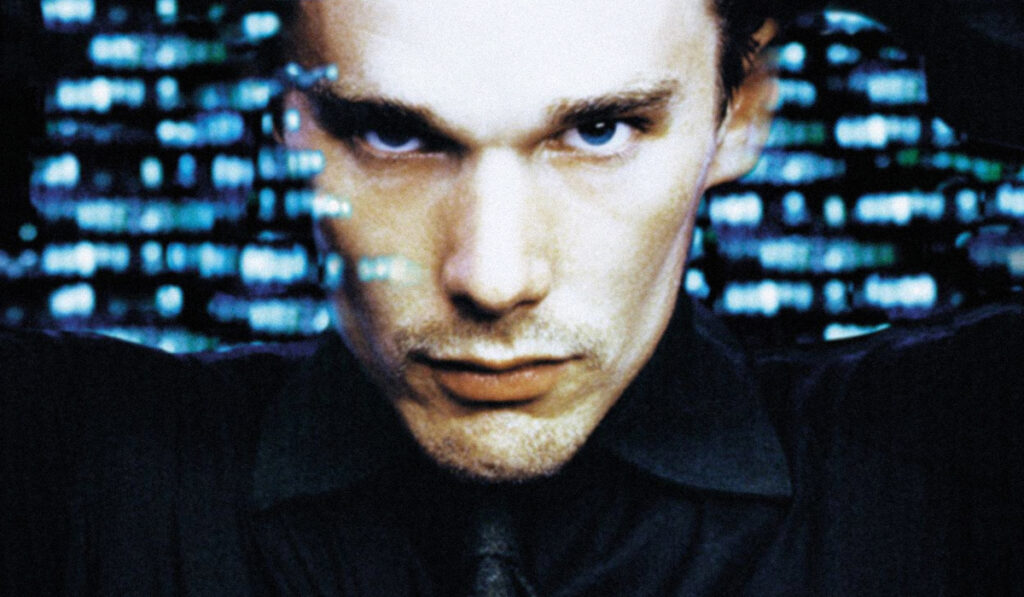

Almereyda chose Ethan Hawke as his Hamlet. He is reportedly the first actor under thirty to play the part in a film. Hawke was eager to take on serious roles and jumped at the opportunity. With Hawke on board, Almereyda began assembling an unlikely crew of American actors, among whom the most intriguing choice was Bill Murray, the actor-comedian, who was cast as Polonius. Diane Venora, a distinguished actress who had been the gender-bending Hamlet of Joseph Papp’s 1983 stage production, accepted the role of Gertrude. The teenaged Julia Stiles, who like Hawke started acting in film as a child, would be a "new" Ophelia. Liev Schreiber, known in independent film circles and a seasoned stage actor who had done his own Hamlet, agreed to be Ophelia’s brother Laertes. The extraordinary Sam Shepard, playwright and sometime actor, signed on to do the Ghost. And the crucial role of the fratricidal Claudius, who looms large in this production, was assigned to Kyle MacLachlan. A David Lynch favorite (he starred in Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet), MacLachlan looks and acts like a department store mannequin but is perfect in this role.

Orson Welles described his own low-budget Macbeth film as a "charcoal sketch of Shakespeare’s play," and Almereyda makes the same claim for his low-budget Hamlet. However, a charcoal sketch implies a clear outline. This Hamlet is more a collage of cut-up and out-of-order pieces that audiences will have to re-assemble in their own minds. Thus, Shakespeare’s inspired lines from act 2, scene 2 are placed at the beginning of the film: "What [a] piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god–the beauty of the world the paragon of animals! And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust?" Hamlet speaks these lines to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in the play, but in the film Almereyda deploys them as a Hamlet soliloquy to establish Hawke’s character. Dare one say that it is better as a soliloquy?

Almereyda gambled that everyone who sees his movie will know the play and will be able to connect the dots he sets out. For example, the entire gravediggers scene ("alas poor Yorick") from act 5 is compressed into a dot-like image of Jeffrey Wright shoveling dirt out of a deep hole. Wright, an overnight success in the 1996 film about the avant-garde graffiti painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, will be unrecognizable even to his most devoted fans. To anyone who is unfamiliar with the play, that gravedigger nanosecond will be a surrealistic incident. Ophelia’s coffin is being buried elsewhere in this modern cemetery and there are no gravediggers and no Yorick Skull in the scene.

As if mindful of what he has left out, Almereyda sets out another dot–a quick cut to a theater poster of Gielgud in "the alas poor Yorick" moment. Gielgud looks almost as ancient as the skull he is holding. It is like a condensed image in a dream–part homage, part ridicule of the venerable Hamlet.

Almereyda has an astonishing theatrical grasp of the play: one can sense it in every choice he makes. But he has no Royal Shakespeare Company pretensions. This is a Jazz Hamlet, with the reckless creativity of bebop. Every directorial improvisation, like the poster of Gielgud, is a riff on some previous interpretation of the play.

The youthful Ethan Hawke gives something less than a virtuoso performance as Hamlet. The lines are quite obviously too much for him. But in this stylish fast-moving production, that is not the disaster one might expect. Almereyda has suited the action to his actors.

Since this is a Denmark without a royal throne, it is not unreasonable to imagine that the son of an American merger king would be an aspiring filmmaker and that his girlfriend Ophelia would be a still photographer. They are the artistically minded anti-establishment children of New York’s new limousine class. They have all of the privileges of wealth but reject the corporate-culture values of their parents. This Hamlet obviously does not want to follow in his father’s footsteps as CEO of a major multinational corporation. And Ophelia is no reclusive virgin. She is a feisty young woman who has her own East Village studio loft with a darkroom to develop her films. Roles like these are not a stretch for Hawke and Stiles. For the first half of the film, Hamlet, when he is not in his apartment watching black and white Pixel videos of his dead father, makes his anti-corporate-culture statement by wearing one of those knitted Peruvian hats with earflaps one sees on flute-playing street musicians. Ophelia wears baggy raver pants and sneakers. Together they are the sullen outsiders at the shareholders meeting where the pin-striped Claudius announces he has replaced his brother, married his wife, and resisted a hostile takeover by Fortinbras.

Although Almereyda sets his Hamlet in New York City and films the action against Times Square, glass sky scrapers, the Guggenheim, and other recognizable landmarks, the imaginative cinematography creates not the gritty reality but an other-worldly New York. The visual location of the film, very much like Shakespeare’s own Denmark, is an imagined actuality–a place outside real time. The Pixelvision on the screen casts ghost-like images that conjure up the something rotten in the state of Denmark. Inter-cut with the lush, high-quality cinematography of the other-worldly New York, it makes a striking contrast.

Almereyda, by eliminating the political, foregrounds the personal Hamlet and Ophelia relationship. Instead of a prince and a commoner, they become star-crossed lovers whose tragic affair is central to this non-dynastic plot. There have been many productions of the play in which Hamlet’s feelings for the frail and pious Ophelia pale next to his love for his true and trusted friend Horatio: "Give me that man that is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him in my heart’s core, ay, in my heart of heart, as I do thee." From first to last Hamlet is gentle and trusting with Horatio, and, as Granville Barker points out, only with him. In the final scene, as Shakespeare wrote it, Horatio proves this love is not one-sided. He wants to finish the poisoned wine and die with his beloved Hamlet. The dying prince begs him to live and suffer awhile, "to tell my story." What greater trust could Hamlet and Shakespeare bequeath to Horatio?

Almereyda de-emphasizes the Hamlet—Horatio relationship and provides Horatio with a girlfriend (Marcellus of the night watch becomes Marcella), who strikingly changes the male chemistry. She is one of only three significant characters who have been added to Shakespeare’s dramatis personae (the others are Thich Nhat Hanh, the Buddhist Guru, and Robert MacNeil, formerly of PBS news). I take it that Almereyda chose to suppress the homophilic and misogynist undercurrents in the play.

Almereyda’s echo chamber nevertheless allows us many of the reverberations of Shakespeare’s play. Several strategies combine to this result. First is the use of Shakespeare’s actual language: cut back relentlessly, those magic words manage to summon the echoes of all the rest. Almereyda’s wit is an unpredictable catalyst. His hi-tech devices shrewdly, ironically, even humorously give Shakespeare’s substance a new style–a style that reminds us that Hamlet has a number of wickedly funny lines. The hi-tech devices also, surprisingly, help the plot along.

A good example is the famous "get thee to a nunnery" scene. Distrusting Ophelia, Hamlet has become stand- offish. His attitude toward her, as reflected in Shakespeare’s lines, changes dramatically in the middle of the "nunnery" scene. To explain that change Branagh and many other directors have created a stage direction (few if any of the original stage directions exist) in which Hamlet sees something that makes him realize that they are being spied on and that Ophelia may be in on it–"Are you honest?"

Almereyda builds on that premise. We are shown Polonius wiring the recalcitrant Ophelia before he "looses" her on the unwitting Hamlet. Hawke’s Hamlet, though wary, cannot resist this passionate Ophelia. They embrace and as his hand caresses her body it encounters the wire–the uncontestable evidence of a hi-tech betrayal. Most of Hamlet’s long speech has been sacrificed but the few words that are left juxtaposed against the wire give the scene a dramatic clarity that many Hamlets have not matched.

Almereyda made a virtue of necessity: he did not ask his actors to attempt the high style of British actors who have been schooled in the prosody, mastered the rhythms of Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter, and can project to the second balcony. The truth is most American actors look silly and unnatural when they make the effort. One need only rerun the video of Marlon Brando trying to do Marc Anthony in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar. Almereyda wisely encouraged his actors to "draw on their own experience and traditions, rather than classical Shakespearean technique."

The cast did just that. The notable exception was Liev Schreiber, who had trained at the Royal Academy and knows how the British do it. It is true that he does not look silly saying the lines, but he is certainly out of place in this cast. His performance has been a litmus test for critics. Those who do not like the film tend to think that Schreiber is the only one in the cast who can act: "The only tragic thing about the … new Hamlet is the lonely spectacle of Liev Schreiber giving a deeply felt, expertly spoken performance as Laertes," wrote Jonathan Foreman of the New York Post. Since I am of the mind that Almereyda’s American re-conception is the inventive strength of the film, it seems to me that Schreiber has made a lonely spectacle of himself. He seems to be declaiming in the spit-flying style of the English stage while the rest of the cast has the typical psychological inwardness of American film actors, whose "method" recognizes the power of the medium.

Sam Shepard reported his own experience trying to master the iambic pentameter of the Ghost. He ordinarily approaches a role by first attempting to understand the psychology of the character he is to play. But Shakespeare’s meter was so insistent he had to deal with the poetry first. Eventually, he worked his way through the language to the psychology and his American Ghost was believably father-like–and not just the sepulchral spirit of most Shakespearean actors. Still, this is film and Shepard’s visual presence on the screen counts for more than his acting. The handsome weatherworn face makes every glimpse of him memorable.

Bill Murray had never done Shakespeare before and Polonius is a difficult role that would challenge any actor. If this is a Jazz Hamlet, Murray’s Polonius is a wonderful improvisation. Instead of trying to make himself into Polonius, Murray riffed his own persona into the part. His first great hurdle was how to speak the all too familiar lines of paternal advice to Laertes. Would he be a prating fool or a wise father? He spoke his homily, pared down to a minimum, as if paying lip service to his own hypocrisy. Establishing his character as an intrusive father he helps the departing Laertes pack and secretly slips a roll of bills into his coat pocket before urging him, "Neither a lender nor a borrower be." Then hugging his son he gives the camera and the audience one of his trademark "Can you believe this?" grimaces. This Polonius is neither wise nor foolish. He is the ingratiating, but ironic, clown that has made Bill Murray a success.

The same critics who think that Liev Schreiber is the only member of the cast who can act pan Murray’s Polonius. What I take to be patented grimaces at the camera they understand as Murray searching for cue cards. There is an entire dimension to this film that can be understood as sophisticated and stylish or sophomoric and inept. Thus one critic complained that there were too many visual distractions that took away from the acting (e.g., Hamlet walking down the "Action" aisle of a Blockbuster Video store while doing the "to be or not to be" soliloquy). But Almereyda, it seems to me, knows exactly what he is doing. Those visual distractions are both ironic and perhaps necessary. Many of Hamlet’s lines are spoken in voiceover, so we do not actually often have the potentially painful experience of watching Ethan Hawke in the act of speaking Hamlet’s lines. It is as though Almereyda understands that Hawke cannot carry it off if the camera catches him in the very act of mouthing his lines.

The "to be or not to be" soliloquy is the ultimate test for an actor, and even a man of Branagh’s talents chose to amplify his performance in a hall of mirrors. Almereyda took something from that. He has Hawke doing the "How all occasions do inform against me" soliloquy while looking into the mirror of an airplane toilet. But for the "to be or not to be" soliloquy Almereyda made another imaginative reach. Before his New York Hamlet goes video shopping, he watches the Buddhist Guru Thich Nhat Hanh on television. Thich is talking about how to coexist with other living things in the natural world–or, in his neologistic phrase, how to "inter be." The Buddhist Guru’s "inter be" soliloquy has all of that holy man’s guileless charm and humility. It is a surprising and ingenious countertext of Eastern transcendence pitted against Hamlet’s anguished existentialism. And the action signs in the video shopping venue for the "to be or not to be" soliloquy reverberate in Almereyda’s ironic echo chamber.

The film also has insider moments for film buffs, as when Ophelia unpacks her handbag of "remembrances" from Hamlet. The last thing she takes out is a little rubber duck. The audience laughs at this childish memento but, in fact, this is Almereyda’s homage to Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki, whose 1987 satire Hamlet Goes Business had Claudius cornering the world market in bath toys. Almereyda’s final ironic improvisation is Robert MacNeil’s epilogue. He comes on after the mayhem of the last act as though it is the PBS news hour. His lines are those of the Player King’s: "Our will and fates do so contrary run that our devices still are our overthrown; our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own." Again the appearance of MacNeil reading the poetry as news provokes laughter. But knowing the lines and where they come from in the play ironizes the absurd humor. If one looks closely and quickly, one sees that MacNeil’s thoughts are not his own: he is reading from a teleprompter.

Although Almereyda gave the actors room to interpret their roles and improvise, he made choices about their lines and thus their characters. The two women in this New York Hamlet are particularly intriguing, and underscore with particular force Almereyda’s inventiveness.

Julia Stiles was determined to play Ophelia as a strong young woman rather than as the fragile victim. She is not a conventionally pretty actress and she abandons any appearance of innocent naiveté. Laertes still has the lines of cautionary advice to his sister on preserving her "chaste treasure" but this petulant New Yorker does not conjure up an image of virginal chastity on the screen. Her strong willed Ophelia goes howling with rage into madness–not because she is broken by the murder of her father by Hamlet, but because it is the only way she can protest what these men have done to her.

Venora is also an interestingly different Gertrude. She has been stripped of almost all her lines and is limited to her presence on the screen. Her Gertrude is radiantly sexual, like a woman who unexpectedly catches fire in her forties, and all of her heat is aimed at the conquering Claudius. But then comes the famous bedroom scene with Hamlet. Many Hamlets, including Olivier and Burton, brought obvious sexual overtones into this bedroom wrestling match. This Gertrude is shaken to the core, and it’s not about sex; it is about her denial. Shakespeare’s play does not tell us whether Gertrude believes Hamlet’s accusation. Recall that she too has watched the play within the play ("the lady doth protest too much")–did she get it? Does she pass Hamlet’s tirade off as "the very coinage of [his] brain"? She has a moment of remorse: "These words like daggers enter in my ears." But Gertrude certainly never turns on Claudius; indeed she is protective when later Laertes threatens him. And in the play as written there is no reason to believe in the duel scene that Gertrude knows she is drinking from the poisoned cup: "The queen carouses to thy fortune, Hamlet" is her line. It seems unwitting; indeed many directors have made Gertrude into a witless sot who is never without a glass in her hand and has no idea what is rotten in Denmark. And Almereyda’s Gertrude also conspicuously takes to the bottle after her bedroom confrontation with Hamlet. In a scene designed to underline her drinking problem, she steps out of the limousine that drops Hamlet off at JFK airport for his banishment to England. Teetering on high heels and holding a glass, she kisses him good-bye and staggers back into the car. This Gertrude’s denial has been undercut by Hamlet’s confrontation. In the duel scene, she gives Claudius an unmistakable look of comprehension before she willfully drinks the poisoned wine. She is on to his poisons and her own complicity.

Ophelia and Gertrude for centuries have been hapless women who go to their deaths by accident in Shakespeare’s play–Ophelia too mad to recognize her danger, Gertrude unwittingly carousing to her doomed son. But Almereyda’s women are made of sterner stuff. Shakespeare’s women are locked into tragedy, and they must die. This Gertrude and Ophelia do it on their own terms.

Hamlet 2000 is an unexpected delight. It may be "caviary to the general." But it was (as I perceived it, and others whose judgments in such matters cried in the top of mine) "an excellent [film], well digested in the scenes, set down with as much modesty as cunning."