The Summer of Theory: History of a Rebellion, 1960–1990

Philipp Felsch, translated by Tony Crawford

Polity Press, $30 (cloth)

The Long Summer of Theory

directed by Irene von Alberti

Filmgalerie 451

Not long ago and in certain small circles of academic life, the word “theory” conveyed a special magic. It signified both sophistication and freedom, elevating its devotees into a rarefied world of European ideas that would bestow the gift of insight into the hidden truth of language, or culture, or history.

Two meanings were intertwined even if they often ran at cross purposes. On the one hand, “theory” carried a hint of privilege, the cultivation of exquisite skills in reading and interpretation that were accessible only to an elite. On the other hand, it implied the hopeful idea of an emancipatory practice, since presumably anyone who wished to “do theory” did so because it promised, someday and somehow, to link up with the moral and political business of transforming the world. If theory was the question, practice was the answer. But even in the years of high enthusiasm for theory, the answer seemed forever deferred for another day.

Today, now that the passion for theory has been largely spent, it can be hard to explain why it was once felt to be so fascinating. Surely its exotic pedigree played a role. Theory, after all, was not the name for a specific doctrine; it was a serviceable if somewhat baggy term for various ideas and intellectual movements that arrived as imports from the European Continent. The high avatars of theory—Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, Louis Althusser—were mostly French, and they had received a rigorous training in the European philosophical canon.

But when their work was translated into English, it seldom received a warm welcome among members of the Anglophone philosophical profession, who tended to see it as an interloper, an unruly child who had scant respect for the established standards of clarity or rational argument. It found a far more hospitable welcome in departments of literature, where it metamorphosed into “French theory,” a rich brew of ideas that left many graduate students intoxicated if often bewildered, though it was best to keep one’s confusion to oneself. In the 1970s and ’80s theory swept through the humanities like a new gospel. Many were converted, some resisted, but few could doubt that they were living through a time of intellectual revolution. Like many revolutions, however, what began in hope eventually petrified into dogma. “Theory” became a fashion, and then lost its shine.

The Summer of Theory is almost the title of both a film and a book (in the film, the summer becomes “long”). They address a story that is far less familiar to Anglophone readers: how theory came to Germany, where it ignited passionate debate among intellectuals and artists and inspired new ways of thinking about literature and society. Both the film and the book are ingeniously crafted, and they are such a delight to watch or to read that they awaken summertime joy even as they speak to weighty themes.

The film, by German director Irene von Alberti, is a brilliantly realized group portrait of three young women—Nola, Katja, and Martina—who share a flat in an industrial wasteland of present-day Berlin. The milieu is a little island of bohemia slated for destruction in order to make room for “Europacity,” a slick new center for global capitalism. (In the years since the film was released, the development has come to fruition.) The protagonists are irreverent but earnest in their aims; they resist the allure of the new economy and thirst for creative expression, whether in the theater, in painting, or in film.

The film is by turns playful and bleak. The three women often encounter young men and pose the question: Is this particular man really necessary or could he just as well be a decorative floor lamp? They wave their hands and, zap: he’s a floor lamp. In a more dispiriting scene, Martina presents her art portfolio to a talent agent who proceeds to mansplain to her about the meaning of her art while imagining how he can make it a commercial success. Confronted with the hailstorm of words she gathers up her art and quits the scene.

Von Alberti is an accomplished German director of strongly feminist convictions and a deadpan style of humor. The Long Summer of Theory, inflected with surrealism and touches of satire, harkens back to La Chinoise, ou plutôt à la Chinoise, Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film that portrays young French Maoists who are plotting an assassination while recording their debates: it was subtitled un film en train de se faire (“a film in the making”). The result was a playful exercise in self-reference. In a well-known episode Godard films a conversation on a train between Véronique, one of the student militants, and Francis Jeanson, an actual professor at the University of Nanterre where the actress playing Véronique had been a student. Von Alberti, too, enjoys these tangles between fiction and reality. Nola is herself a young documentary filmmaker, and the film we are watching is the record of her efforts. She is shooting an earnest if somewhat rambling film on the topic of “self-optimized individuals and collective consciousness.” The topic is meant ironically; what truly interests her is the question of whether there’s any happiness beyond the immediate present. Lingering over the action is the echo of Lenin’s famous question: “What is to be done?”

Unlike Lenin, Lola doesn’t know what should be done. Over the course of the film, we follow her as she traverses Berlin, through parks and into offices and onto rooftops, where she conducts interviews with prominent German theorists (real ones, not actors) such as philosopher Rahel Jaeggi and cultural historian Philipp Felsch. Felsch is the author of The Summer of Theory, the book from which von Alberti has borrowed her film’s title.

The connection between film and book is loose but instructive. Felsch tells the history of the German passion for French theory during the 1970s and ’80s; von Alberti’s film (and Nola’s), is an open-ended inquiry into what guidance we can expect from theory today. While Nola waits for Felsch in a park to conduct an interview, she passes the time by reading his book. Over the course of their conversation, however, it dawns on her that the intellectual passions of the past generation may not be so easy to revive. “Have we now entered ‘the long winter of theory’?” she asks. Have we given up on the old unity between reading theory and political revolt? Yes, responds Felsch. People no longer read with the intensity they once did. He describes a paradox: with the rise of social media, the entire public sphere is now awash in the written word. But to ponder all of that text would be a mathematical impossibility. Everyone writes, nobody reads.

Felsch is a brilliant stylist and his book is a true joy to read. Does this falsify his claim in the film? Nola is reading his book, after all, and she represents us. It is composed in a breezy and ironic style that takes intellectuals less seriously than intellectuals like to take themselves—describing not only their ideas but also their lifestyles and their affairs—but it is done with such deftness and wit that one seldom fears the ideas have suffered any distortion. To be sure, Felsch does not presume to be a grand theorist himself. Ideas for him are not candidates for evaluation; they are like characters in a play. His book is an exercise in intellectual history, not philosophy; he wishes to understand how theory became a fashion in Germany, how it arose and why it declined. But perhaps this is his point: if we are living in the winter of theory, the only task that remains for us today is retrospective.

To bring this tale into focus, Felsch organizes his history around the fortunes of a single publisher, Merve Verlag, an upstart little press founded in 1970 by Peter Gente and his wife Merve Lowien. The publisher’s early books were all pocket-sized, often pirated or bootleg editions of brief texts translated into German from the French. Their titles could be enigmatic (like “Rhizome,” a 1977 essay by French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari) or deceptively simple (like the 1978 lecture-turned-essay “What Is Critique?” by Foucault). The first editions were cheaply made, stapled, not bound, and immediately recognizable by the minimalist but colorful rhombus design on their covers. The publisher still exists today, and in bookstores of a certain kind, one still comes across a full wall of Merve book in a vertiginous, multicolor display. But these days they are more often found in museum bookshops, and they no longer convey the promise of political utopia.

To focus all this attention on a single publisher may seem frivolous, but as a skilled cultural historian Felsch knows that what might appear marginal to an era can often define its center. The history of Merve Verlag is nothing less than the history in microcosm of a larger revolution in German intellectual life. (A similar story has been told about Semiotext(e), the pocket-sized press that specialized in translations of French theory into English, founded in 1974 by the late Sylvère Lotringer.)

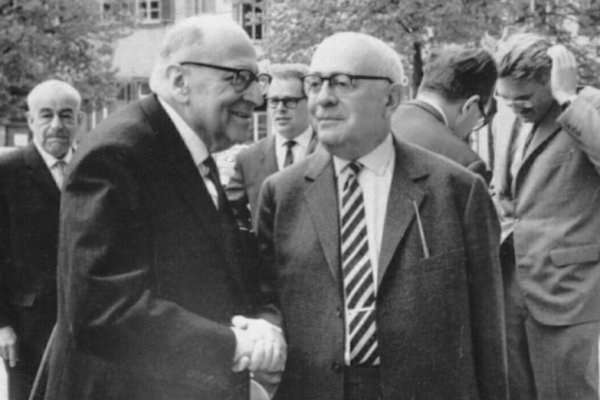

By the mid-’60s, the ascendant generation of German students had already started to rebel against the official culture of political conformism and capitalist expansion that prevailed during the thirty-year period of economic growth known as the Wirtschaftswunder. Some looked for guidance to the Institute for Social Research (popularly called the Frankfurt School), an interdisciplinary group of émigré intellectuals such as Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno who had returned from America after the war. Admired by student radicals but vilified by conservatives, the Institute became an unlikely if inspirational force on the German left. Its theoretical orientation was vaguely Marxist but hardly revolutionary, since it saw the modern world as a fallen realm of near-total commodification in which there remained only the smallest glimpse of political possibility. During the war, Adorno had composed Minima Moralia, a book of lacerating aphorisms that braided together philosophical and cultural criticism in inimitable if often forbidding prose. Published in Germany in 1951 just after Adorno’s return to Europe, the book became a kind of breviary for young readers and a model for what theory might be: essayistic, systemless, and ambulatory. Theory was a critical practice, or even a lifestyle.

The founders of Merve Verlag set out to create a publishing house that would follow this vision of what theory might be. But they also recognized that this would mean a rebellion in the ranks of the West German intelligentsia: they would need to free themselves from the authority of established German publishing houses such as Suhrkamp Verlag, the press founded in 1950 whose imposing books in philosophy and social theory stood as the very embodiment of the new Germany’s left-liberal ethos. This was the spirit of enlightened rationalism and universalist ambition that readers would come to associate most of all with Jürgen Habermas, the philosopher who had once been Adorno’s assistant in Frankfurt but who by the 1970s had emerged as the foremost representative in the second generation of Frankfurt School critical theory.

There was in fact an intimate bond between the Institute and Suhrkamp; the press would publish all the major titles by the Institute’s members. The literary critic George Steiner went so far as to describe the left-liberal spirit of West Germany as “Suhrkamp Culture.” In 1965 Adorno could plausibly declare that this was a “time of theory,” and by the 1970s Suhrkamp had secured a wide readership for its academic series (the suhrkamp taschenbuch wissenschaft, or stw), which presented all of its paperback volumes in a sober and uniform dark blue. Among the first titles to be published in the stw series was the first volume in the now twenty-volume complete edition of Adorno’s published works, released in 1970 a year after Adorno’s death.

Over the next decade theory would change; it became more volatile, more experimental. When the editors at Merve Verlag began to carve out their own niche in the competitive world of German publishing, they found themselves pursuing a new and unfamiliar path that diverged sharply from the ethos of rationalism that made Suhrkamp such a formidable presence. One obvious change was a growing distance from Marxism. In its early years, Merve published its books in a series that carried the label “International Marxist Discussion.” Later the series was rechristened “International Merve Discourse”—a sign of a certain shift in ideological orientation, away from the sober language of dialectics and toward the new theories that were imported from France.

The personal situation at the press also changed. When Gente met another woman, Heidi Paris, his first wife Lowien left the press (though it would retain her first name). Paris, younger and more venturesome in her interests, embodied the spirit of May 1968. Like many students of the time, she found Marxism sclerotic, a rigid system that inhibited the creative powers of the libido and the arts, and it was partly under her direction that the press began to read and publish works in translation by French authors such as Foucault and Jean-François Lyotard. Felsch assigns great importance to the activity of reading. Neither Gente nor Paris had the ambition to become theorists themselves; reading, they felt, was already a transformative practice. “Reading Foucault is a drug,” Paris said, “a head rush. He writes like the devil.” In 1976 she and Gente convened a reading group to make their way slowly through Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, one of the more challenging texts in the new wave of French philosophy. The task took them five years.

What explains this enthusiasm? Part of the answer is surely the widespread perception on the left, in Germany as elsewhere, that the Marxist paradigm had been exhausted. The French translation of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago in 1974 brought to light the astonishing brutality of Soviet communism and helped to solidify new intellectual movements that were skeptical not just of capitalism but of all forms of rationalized institutional power. Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975) typified this new vision of modern society as a total system of surveillance and imprisonment. The target was no longer a specific class or economic arrangement but the basic fact of social structure as such. Foucault saw that all attempts to introduce greater order into institutions only had the effect of enhancing their power, to the point where the human subject itself became complicit in its own confinement. In a conversation with French Maoists Foucault warned that even forms of popular justice were suspect. The simple placement of a table between judges and the accused was a sign of an emerging disciplinary society.

The waning of interest in Marxism as a social theory left in its wake an intellectual vacuum in which new passions could flourish. A major beneficiary of this change was the rediscovery of Friedrich Nietzsche, whom the Nazis had tried to fashion into an ideological forerunner, but who now appeared to German readers in a new and unfamiliar light. In a culture that was still reckoning with the memory of the Third Reich, the renewal of interest in Nietzsche’s philosophy at home was possible only because it returned after undergoing dramatic reinterpretation abroad. French philosophers in the late sixties and seventies were reading Nietzsche with fresh eyes and without the burdens of history. In 1972 Lyotard gave a paper at a conference on “Nietzsche aujourd’hui” in Cerisy-la-Salle, in which he called Marxism “une dérive,” a drifting off-course; instead he called for a principle of “intensity,” a shattering of all hierarchies. He praised not politicians but “experimental painters, pop, hippies and yippies,” whose lived experience “offers more intensity . . . than three hundred thousand words of a professional philosopher.”

Gente and Paris were excited by this vision, and in 1978 they published a German translation of texts by Lyotard in a new hot-pink edition, Intensitäten, that became a Merve bestseller. Other lectures on Nietzsche followed, including a German version of Deleuze’s introduction to Nietzsche. As Felsch explains, the overall effect of this new-Nietzsche wave was to introduce a spirit of playfulness into German philosophical discussion that Felsch describes as liberation. “Those who read Nietzsche without laughing,” Deleuze wrote, “have, in a sense, not read Nietzsche at all.”

But if Nietzsche brought laughter into German philosophy, the German Autumn of 1977 brought a wave of violence—kidnappings, murder, and hijacking by affiliates of the Red Army Faction—that threw the left into disarray. The Merve editors drove to Paris where they visited with Foucault and discussed the latest events. Their conversation, as related by Felsch, has been preserved on tape. Gente expressed his fear that, in reprisal for the terrorist acts, West Germany had turned into a police state; Foucault responded in terms that were somewhat baffling. Rather than addressing the particulars of the present crisis, he expatiated at length on broad points of history with allusions to the seventeenth century and the Sun King. The problem, Foucault said, was that the RAF still imagined that it was fighting an ancien régime. What it failed to recognize was that the nature of modern power no longer resided in the state. The urgent thing was to understand the “microphysics of power,” the dynamic of a system without center by which power circulates throughout the social body.

After 1977, Felsch writes, “‘theory’ was not the same.” Merve Verlag continued to publish works in translation, but its reputation for cutting-edge theory began to fade. Its gains in wealth meant that it could produce books in hardcover editions that were now shelved alongside other academic tomes in university libraries. With increasing frequency, Merve produced books of theory that exhibited a kind of aesthetic sheen that seemed best suited to the “white cubes” of the art world. For a publisher that had advertised itself as the outsider its success was not without irony. As Felsch says, “What it lost in its triumph was its aura of danger.”

In the mid-eighties there came a new volley of criticism from Habermas, the doyen of critical theory, whose 1985 book, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, offered both an historical survey and a sober verdict on the failures of the intellectual avant garde since Nietzsche. The chapters on Derrida and Foucault were especially noteworthy for their vigor in dispatching these avatars of French poststructuralism as politically irresponsible and potentially irrationalist thinkers who were indifferent to the burdens of public-facing philosophy. Many found this verdict excessive and simply uncomprehending, but it laid out the terms of disagreement between critical theory and “French theory” that would endure for many years. Meanwhile, Merve Verlag underwent a shift in editorial leadership. Heidi Paris committed suicide in 2002; five years later, Peter Gente retired to northern Thailand, where he died right around the time that Felsch was finishing the research for his book.

Felsch has a knack for interweaving intellectual history with personal anecdote without descending into mere gossip. But for those who care most about the substance of the ideas, his narrative may occasionally raise the suspicion that the passion for theory in Germany was as much fashion as philosophy. Although Felsch does not dwell on matters of method, his book exemplifies a certain way of describing the history of philosophy without really doing philosophy.

To be sure, intellectuals, especially in the European or so-called “Continental” tradition, have long been aware of the fact that philosophy is not an exercise in world-transcendence; it is born out of history, and it is ultimately a practice of reflecting upon who and what we are in our own historical moment. As Hegel once said, philosophy is “its own time apprehended in thoughts.” But there is a nonetheless a distinction between situating intellectuals in their historical milieu and entertaining the question of whether their ideas have any merit. With the skills of a cultural historian, Felsch has given us a vivid and often entertaining portrait of intellectuals for whom theory was not simply an academic exercise but a way of life. This is what philosophy has always been, from the Stoics to Foucault. But do we really need to know that Foucault was hanging out in Berlin nightclubs with David Bowie? Perhaps no, perhaps yes. One cannot help but feel a nagging suspicion that the passion for French theory became just a tad too self-conscious of its own status as a cultural trend.

It is this acute awareness of its own image that was responsible for turning the movement into what François Cusset called (in English) “French theory,” a collective noun designating not a discrete body of ideas but a general sensibility that was brought to life only when it was packaged for export abroad. Cusset’s book-length study of this remarkable phenomenon was first published in French nearly two decades ago, and it was clearly written for French readers. Its stated purpose is a sociology of the American reception, but its tone hovers between skepticism and (occasionally) disdain. For Cusset, “French theory” is a “weird textual American object,” an interpretative monster that was the fruit of “decontextualization” or even “taxonomic violence.” He seems reluctant to accept that all intellectual activity involves a kind of translation, since there is no such thing as an isolable language or culture, and no theory or philosophical claim is so fixed to its native context that it cannot be moved and fire the imagination of readers elsewhere. As Edward Said once observed, “ideas and theories travel—from person to person, from situation to situation, from one period to another.” What I mean and what you mean may converge but will never reach identity. The heroic work of the translator is not to reproduce an exact replica of the original but to broaden the bridges of mutual understanding. Shutting down those bridges would be tantamount to shutting down meaning altogether.

Felsch is more sympathetic to the many theorists and readers who populate his tale. Their aim, he explains, was “to cultivate Parisian philosophy in the German-speaking countries, not just in translation, but in native assimilation.” Still, the attempt to turn oneself into a French theorist could easily result in “baroque stylistic lapses,” a kind of playacting or mimicry where one adopted the mannerisms, both written and spoken, of les philosophes français. In the eighteenth century, long before anyone had ever heard of poststructuralism or semiotics, Jean-Jacques Rousseau had reacted with violent allergy to the affectation and theatricality of the Parisian salons. Those of us who lived through the twilight age of American enthusiasm for French theory in the late 1980s and ’90s could often detect a hint of artifice when colleagues took up the new trend in philosophy with all the zealotry of converts. There were distinctive mannerisms, shibboleths or terms of art, by which the initiates could know their kin. In an era when irony and self-reference became commonplace tropes in literature and mass culture, it was hardly surprising that (to quote Felsch) “theory was becoming indistinguishable from the parody of theory.”

For those who disliked French theory, parody became the preferred weapon. In a mocking 1986 essay entitled “Lacancan und Derridada,” the professor of literature Klaus Laermann heaped scorn on the entire trend, accusing his German colleagues of “Frankolatrie.” Among German readers the essay met with broad acclaim; it even won the Joseph Roth Prize for journalistic writing. Even better known was a 1996 incident in the United States, when Alan Sokal, an NYU professor of physics, resorted to a similar stratagem of parody, tricking the editors of the academic journal Social Text into publishing an essay that seemed to suggest that gravity was a social construct. Sokal knew that what he had written was nonsense, and some saw the episode as a scandal, the last nail in theory’s coffin. But the amusement of such cases only goes so far; satire, after all, is not the same thing as rational argument. Theory may at times verge on self-parody, furnishing its critics a glimpse of an Achilles heel. But something is lost when one resorts to parody in lieu of critique.

Parody may be the final point of contact between Felsch’s book and von Alberti’s film. The slick art-promoter in the film who meets with Martina—and who, when perusing her portfolio, nearly drowns her with jargon—is speaking in a language that sociologists Alix Rule and David Levine have identified as “International Art English,” a specialist’s patois that “drags around clichés of theory discourse wherever it goes.” Felsch ends on an uncertain note, worrying that theory may be entering a winter phase. But he is too admiring to cheer its passing. He writes in a style of bemused neutrality, as if in the knowledge that all intellectual movements are destined to suffer the same fate: beginning with promises of radical transformation, only to shed their magic and cede their prestige when new trends come on the scene.

Perhaps Felsch’s answer to Nola is right; perhaps we are living in a period of decline. There are good reasons to fear that the practice of reading difficult texts is disappearing. In the subways and city parks, more and more people are cocooning themselves in the private glow of their own digital cosmos. They do not so much read; they scroll. They also text and they tweet, but the Twitterverse is a place of combative self-display that bears little resemblance to Habermas’s ideal of a public sphere.

All the same, the intellectuals who appear in von Alberti’s film serve as good evidence that theory is not dead and that public-facing criticism continues to thrive. It is an unfortunate truth that the sort of theory that flourished in the last decades of the twentieth century eventually descended into scholasticism, where real questions of suffering and social transformation were obscured. But we should not mistake the fate of one intellectual fashion for the general fate of theory. Other summers will come.

Independent and nonprofit, Boston Review relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate or become a member.