The Critical Writings of Ingeborg Bachmann

Edited and translated from the German by Karen R. Achberger and Karl Ivan Solibakke

Camden House, $100 (cloth)

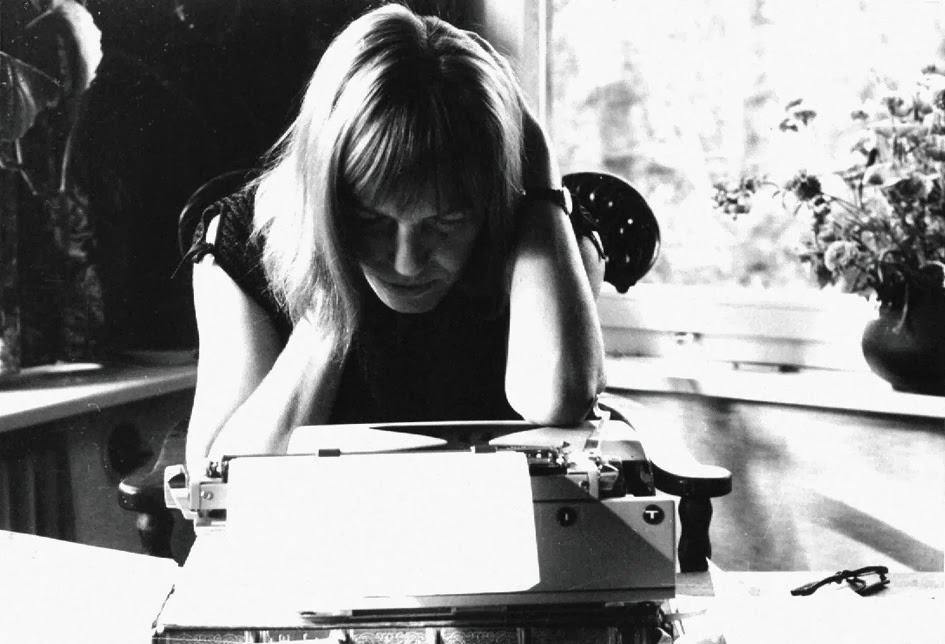

What does it mean to be a person? The question may sound pat in an age so alert to the fluid nature of identity, but for the celebrated Austrian author and antifascist feminist Ingeborg Bachmann, writing in the wake of World War II, it was raw and real to the point of linguistic and psychological breakdown.

One sign of this struggle can be seen in her nameless protagonists. In the title story of her 1961 collection The Thirtieth Year, an unnamed male narrator wonders “whether one could without harm believe oneself to be oneself and whether that was not also a form of insanity.” Behind these words it is hard not to hear existentialist philosopher Søren Kierkegaard on the despairing self, that “relation which relates itself to its own self.” Selfhood is a sickness unto death, Bachmann often seems to be saying, and women had it the worst, ground down by a patriarchal violence that pervaded everyday life long after war was said to have ended. (“Fascism is the first thing in the relationship between a man and a woman,” she said in a late interview.) In Bachmann’s stylistically daring 1971 novel, Malina, whose depiction of “female consciousness” Rachel Kushner has called “truer than anything written since Sappho’s Fragment 31,” another unnamed narrator, this one quasi-autobiographical, struggles to know who she is in relation to her lover (Ivan) or even her mysterious roommate (Malina). “I, me, myself—that’s all been a mistake for me,” she comes to feel before disappearing into a crack in her wall, snuffed out of both the apartment and the novel in which Bachmann has tried hopelessly to affirm her narrator’s existence.

Naming and being: these are the lodestars around which Bachmann’s work revolves. If these sound like philosophical concerns as much as literary ones, that is because for Bachmann they were. Though best known today for her poems and novels, Bachmann was a serious student of philosophy, an incisive essayist, and an influential commentator on Europe’s postwar intellectual and artistic scene.

A new volume of her critical writings, edited and translated by Karen R. Achberger and Karl Ivan Solibakke, makes this other dimension of her work available to readers in English for the first time, recovering the thought of a poet so revered in her time that she graced the cover of Der Spiegel, Germany’s most influential weekly news magazine. Running from Bachmann’s early essays and radio talks of the 1950s through lectures, speeches, and other reflections on music, visual art, and modern literature completed before her tragic early death in 1973, these selections complement translations from her diaries and correspondence and showcase the critical mind of a literary artist consumed by the interrelations of philosophy and poetry, politics and prose, all against the backdrop of a society remaking itself in the shadow of Nazism.

What unites these diverse reflections is an anxious desire to be liberated from the prison-house of language. Again and again Bachmann shows how “the flawed language that has been passed onto us” can lead us to question what we know to be real, our own suffering selves included, and she asks what it means to grapple with these antinomies of world and word as public and political matters, not just private ones—indeed what it means to be a writer at all. “If we had the word, if we had language, we would not need weapons,” she said in a 1959 lecture. Having lived through the war herself, she meant it.

This is not to say her work is unremittingly bleak. In places it certainly bears the gravity of so much postwar German-language writing, but at the same time Bachmann refused to resign herself to despair. Her inventive prose inevitably finds its way to rapture in the emancipatory act of expression, the utopian power to remake the world by the word. “A storm of words starts in my head, then an incandescence,” is how Malina’s narrator describes the exultation that occurs when “a few syllables begin to glow, and brightly colored commas fly out of all the dependent clauses and the periods which were once black.” If these strivings to find the “right phrases” spring from a very different time, they are all the more remarkable for the way they continue to speak to our own.

Bachmann followed an unusual path to early renown as a poet. Born in 1926 in Klagenfurt, Austria, a small rural city just north of the border with Slovenia, she began writing at age ten, a few years after her father, a school teacher, had allied himself with the Nazis. Bachmann felt her childhood ended in 1938 when Hitler’s troops marched into town, but even at the height of the war she refused at one point to enter an air raid shelter, choosing instead to sit in the garden and “carry on reading when the bombs come,” as she records in her War Diary.

After universities reopened in the fall of 1945, she began her studies at Innsbruck but moved to Graz and then finally in 1946 to Vienna, one of the epicenters of European philosophical thought. There she specialized in philosophy of language and science, absorbing the logical positivism famously associated with the city through such “Vienna Circle” figures as Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath, and Moritz Schlick. In 1949 she completed a dissertation on the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger, her naïve hope being “to bring the great man down.” For Bachmann, Heidegger’s thought was “inadequate for an expression of living feeling.” Already the inadequacies of received language—and the search for a more authentic one—had begun to consume her.

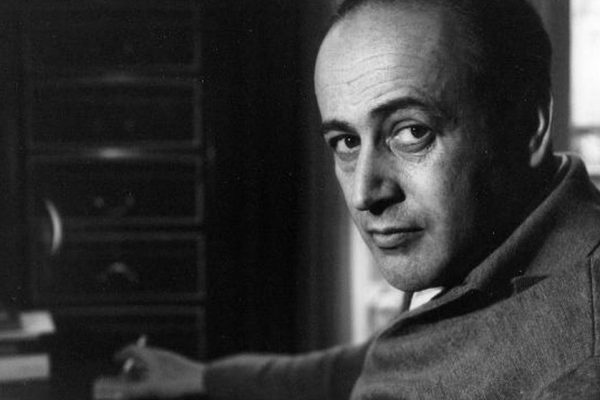

It is not a coincidence that a year before Bachmann took her doctorate she had turned her mind more intensely to poetry. At a party in Vienna in May 1948 she met the poet Paul Celan, a newly arrived German-speaking Jewish refugee from Romania whose parents had died in the Shoah. The two fell in love, and Bachmann began writing her first serious poems. Celan left to settle in Paris a month later, but she stayed in Vienna in order to take a job writing scripts for a popular soap opera called The Radio Family.

By 1954 she had moved to Rome, where she would remain for the rest of her life, later saying that Italy was the country that taught her the “art of living,” allowing her to escape the poisonous underbelly of Nazism that still plagued Austrian society. Despite several failed attempts to keep things going with Celan, their relationship had run its course by 1957; after that they maintained only sporadic contact by phone and letter, but Celan remained a lifelong influence, emotionally and poetically. When he took his own life in 1970, Bachmann’s grief was so deep that she revised the finished draft of Malina, adding in the narrator’s declaration: “I loved him more than my life.” Three years later she herself would succumb at age forty-seven to burns she suffered while smoking in bed.

Though tragically cut short, Bachmann’s career was meteoric. In 1952, a month shy of her twenty-sixth birthday, she was invited to read at a meeting of Gruppe 47, the powerhouse association of writers founded to renew German letters in the post-Nazi era. She won its prestigious literary prize the following year—many more prizes would follow over the years—and in short order published two highly acclaimed volumes of poetry, Borrowed Time (1953) and Invocation of the Great Bear (1956). Each volume tapped deep strains of German Romanticism while casting a cold eye on the postwar world, leading readers to feel that the lyric beauty of Goethe and Heine had been given new life, even though the lush landscapes her poems invoked remained only tentatively vibrant beneath the “corpse-warm foyer of heaven.” Before the decade was out she had produced three radio plays, begun collaborating with the gay communist composer Hans Werner Henze (who also had moved to Italy, fleeing German homophobia and political oppression), and was invited to deliver the first Lectures on Poetics at the University of Frankfurt. By age thirty-four, having taken up with the Swiss novelist and playwright Max Frisch, Bachmann sat atop German letters, the most feted poet of her generation.

Despite this early renown, in the 1960s she abandoned poetry for prose with the publication of The Thirtieth Year, a move met with consternation and derision by readers and critics alike. Poetry, she thought, was no longer capacious enough in a society she viewed as “fraught with unnamed peril.” In delving into the ills of contemporary life, the volume paved the way for what became her unfinished Todesarten (Ways of Dying) project: a series of linked novels, beginning with Malina, that would explore the brutalities of history wrought upon the everyday lives of women. The narrator of Malina observes of Vienna that “people don’t die here, they are murdered.” Bachmann intended to show the various ways these murders took place, commenting in remarks prepared for a 1966 reading tour that “these crimes are so subtle that we can hardly perceive or comprehend them, though all around us, in our neighborhoods, they are committed daily.” In that same late interview where she speaks of the fascistic elements of relationships between men and women, Bachmann pointed out that fascism “doesn’t start with the first bombs that are dropped; it doesn’t start with the terror you can write about in every newspaper. It starts in relationships between people.”

The Ways of Dying project exhibited those more quotidian terrors that had so often gone unnamed and unopposed. The titular character of Requiem for Fanny Goldmann struggles to flee the memory of her Nazi father’s suicide, drinking herself to death after her lover leaves her for another woman and then writes a novel about her, imprisoning her narrative within his own. The protagonist of The Book of Franza, having survived a repressive marriage to a psychiatrist, is brutally raped and bludgeoned to death by a total stranger. Narratives, memory, and history lay siege to each of these women, the ultimate coup de grâce being what the narrator of Malina sees as “letters, syllables, lines, the signs, the setting down, this inhuman fixing, this insanity which flows from people and is frozen into expression.”

Bachmann was thus many things at once: a poet whose vatic, intimately voiced poems are still known to every German-speaking schoolchild, but whose piercing prose on patriarchal violence helped to pioneer second-wave European feminism; a deeply philosophical thinker, but who effectively abandoned both philosophy and poetry at the height of her early fame; and a utopian who, like the narrator of “The Thirtieth Year,” believed there could be “no new world without a new language,” yet who also felt acutely, as she put it in a late speech, that writing was “a compulsion, an obsession, a damnation, a punishment”—indeed that “language is punishment.” The challenge of sorting through these conflicting forces is no small part of the allure of Bachmann’s work.

It did not help that she was a very private person, as she admitted in a 1972 speech. “Only when I am writing do I exist,” she said. “I am nothing when I am not writing. I am a complete stranger to myself, have fallen out of myself, when I am not writing. And when I am writing, you do not see me, no one sees me.” Here was another of the antinomies of writing: though Bachmann felt language to be an obstacle to the full expression of being, only when immersed in it does she feel herself. Achberger and Solibakke help us to see behind this self-imposed curtain.

After an opening section of brief autobiographical reflections, which speak to her childhood and literary roots “in a world in which many languages are spoken and through which many borders flow,” The Critical Writings turns to Bachmann’s most philosophical writing, dating from the early 1950s. Her thought of this period is firmly rooted in the history of logical positivism she absorbed as a student—in particular, its concerns with the logical analysis of ordinary language (rendering everyday speech more precise by logical formalism), and its repudiation of sentences that cannot be verified by the empirical methods of the natural sciences (even those sentences that may seem, on the surface, to be meaningful). Bachmann had drawn on these resources in her critique of Heidegger, but she was also sensitive to what a character in her 1953 radio dialogue on the Vienna Circle called an “excessive scientism.” “The impression is that all questions that concern human beings are evaded,” this critic says.

Logical positivism thus looked like it jeopardized not only nonsense metaphysics but even “a large part” of science’s “previous statements” and “the largest part of the humanities.” In the wake of a war waged by fascism, “a philosophical system that has no consideration for the human being, including the whole wealth of his existence and the abundance of his problems, one in which there is no philosophy of the person, cannot sustain the demands of our time,” Bachmann’s character says. The question was inevitable for a writer concerned with politics, much less with poetry. Not that the Vienna Circle had been dogmatically apolitical: on the contrary, Neurath and Carnap, for example, were deeply involved in left-wing politics. But there was a definite tension between their political activities and the room their philosophy made for political and ethical expression.

Bachmann found a way out of this trap in Ludwig Wittgenstein: it was his work, she thought, that “might bring a sea change, the end of positivism without abandoning its insights.” Her 1953 essay, “Ludwig Wittgenstein—A Chapter of the Most Recent History of Philosophy,” written two years after the philosopher’s death, “initiated a Wittgenstein renaissance” in Austria in the 1950s, Achberger and Solibakke note. Wittgenstein had died “the most unknown philosopher of our time,” Bachmann points out—his one published work, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), inaccessible to all except a “small circle of experts,” and himself having withdrawn to a life of solitude. Again and again, in this essay and elsewhere, Bachmann reflects on the Tractatus’s enigmatic final sentence: “What we cannot speak about, we must pass over in silence.”

For Bachmann, the encounter with this puzzle was formative. Logical analysis set limits to language, yet in doing so it seemed to cordon off precisely “the solution of the problems of our lives.” What is the role and function of the writer if language cannot say what is real, or at least what we feel to be real? Is she condemned to dabbling in nonsense, or can she give voice to what the positivists say cannot be spoken? The answer, Bachmann sensed, lay in Wittgenstein’s “anticipating the unsayable”—what “might not be representable” but “still manifests itself and is reality.”

It would be hard to overstate the significance these ideas appear to have had for Bachmann, steering a course as they did between the “silence” of radical positivism and the “irrationalism” of German metaphysics. She developed them further in another two radio dialogues, “Logic as Mysticism” and “The Sayable and the Unsayable.” The title of the first echoed, as Bachmann almost surely knew, a 1914 essay by the British logician and philosopher Bertrand Russell, “Mysticism and Logic,” which had embraced “the elimination of ethical considerations from philosophy.” Both dialogues were composed within a year after the publication of Wittgenstein’s second major work, the Philosophical Investigations, in 1953; Bachmann brought it into conversation with the Tractatus.

The dilemmas of positivism were now even more sharply and urgently rendered. With “ethics” at risk of being “jettisoned” as unverifiable nonsense, the character playing the role of a critic in the second dialogue fears a “zero point . . . in Western thought, the realization of an absolute nihilism, one that not even Nietzsche, the eradicator of traditional Western value systems, was able to conceive.” Yet not all hope was lost. The “boundaries” set by language, another character in the dialogue observes, “are not mere boundaries but also fissures through which epiphanies can enter.” As Wittgenstein himself put it in the Tractatus, “There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.” This was the door that, for Bachmann, opened onto the possibility of seeing “the problems of philosophy in entirely new frames of reference,” as a speaker concludes in “Logic as Mysticism.”

What Bachmann found in philosophy, in short, was a crisis of language—not a facile or merely academic one, but rather an existential “aporia,” with the weight of the most sophisticated developments of twentieth-century philosophy behind it, that threatened the reality of so much lived experience. Her way out of these entanglements of philosophy was her way into the emancipation of writing. She found in the promise of the “unsayable,” in particular, a way to push back against oppressive forces that kept the truth from being spoken, the “reality that we are not able or permitted to imagine” from being named. She thus strove to write the world as it is—in order that it might be redeemed and transformed.

This attention to language runs through Bachmann’s reflections on modern literature and music as well. In her brief 1953 essay on Kafka’s novel Amerika, what Bachmann values is “precisely the pure, clear language, which almost pedantically does justice to even the paltriest thing.” In a lengthy radio dialogue on the life and work of mystic philosopher and political activist Simone Weil, Bachmann comments on Weil’s “fanatic” devotion to “precision” in the exercise of writing, which was “important as long as the distance between ‘knowing’ and ‘knowing with all one’s soul’ had not been bridged.” And in an extended 1954 essay on The Man Without Qualities, fellow Klagenfurt native Robert Musil’s multivolume, unfinished novel of ideas, Bachmann dubs the protagonist Ulrich “a utopian” because “his sense of a reality that has not come about yet, of possibility, propels him into an intellectual battle, one fought out on the frontline of a reality that is yet to be created.” Musil thought utopia had to be understood “not as a goal, but as a direction.” Together these reflections shed light on Bachmann’s turn away from poetry. Though she never entirely abandoned it—she continued to write poems privately, publishing some of her best in the late 1960s—she did come to feel that the times had outrun what “epiphanies” poems had to offer. But having found in philosophy an opening for poetry, Bachmann now sought a way to manifest the reality of her day in stories and novels as well.

Bachmann’s five Frankfurt lectures, delivered over the winter of 1959–60, mark the transition into this new period. In the first, concerned with “questions and pseudo-questions” on contemporary literature, she rejects the concerns of the daily press (“Is the psychological novel dead?”) and literary criticism (“everywhere profundity, positions, points of view, mottoes, fact sheets, catchwords derived from intellectual history”) to begin instead with the most basic question of all: “Why write? To what end?” Given her dramatic turn from poetry to fiction, undoubtedly Bachmann searched for the answer to these questions deep within herself, though she also saw such self-doubt as endemic to modern writers as a whole. “The relationship of trust between I and language and thing is badly shaken,” she notes, sympathizing with the narrator of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Letter of Lord Chandos (1902), who has “lost my ability to think or speak coherently at all.” Bachmann makes a point of observing that this prose work marked for Hofmannsthal “a turning away from aestheticism” and the “pure, magical poems of his early years”—no doubt an important touchstone for her own turn away from poetry.

Despite all this “self-doubt” and “despair” about language, Bachmann sees in this anxiety the very seedbed of “a new perception, a new feeling, a new consciousness.” New literature that commands our attention, she insists, arises not just on behalf of “aesthetic satisfaction,” novelty for novelty’s sake, but rather from a “moral [impulse] before all morality,” “an impetus for a thinking . . . that wants to comprehend and achieve something with language and through and beyond language. Provisionally, let us call it: reality.” She condemns the compartmentalization of contemporary life, the disjuncture between private domesticity and public brutality: “Here inwardness and meaningfulness, conscience and dream—there utilitarian purpose, meaninglessness, cliché, and speechless violence.” And she promises her lectures will resist the “precautionary measure” of cutting art off from society—“rendering it harmless” by treating it as a domain unto itself—and look instead to “a literature that embodies a serious and uncomfortable spirit striving for change.”

In the second lecture, “On Poems,” Bachmann again sees a critical “change” having occurred in the poet’s plane of regard as result of being “moved into a fatal solitude.” Denouncing the fascist leanings of German poet Gottfried Benn and American poet Ezra Pound, she observes “it was but one small step from the pure heavens of art to consorting with barbarism.” What is needed is “a new law between language and the human being,” one that can legislate a relation between beauty and horror more dynamic than simply cynically switching out one for the other. Fleetingly, at the lecture’s end, she quotes Celan’s description of himself as “wounded by reality and in search of reality” as the new avenue that has opened—one in which the writer, out of necessity, “goes toward language with his very being.”

Bachmann’s most trenchant expression of the interrelations of language and identity occur in the third lecture, “Concerning the I,” which traces varying renderings of the self in literary narrative. Bachmann asks:

For what is the I, what could it be?—a star whose position and trajectories have never been completely determined and whose core has not been comprehended in its composition. That could be: myriads of particles composing the I, and at the same time it seems as if the I were nothing, the hypostasis of a pure form, something akin to an imaginary substance, something that refers to a dreamed-up identity, a code for something that takes more pains to decipher than the most secret orders.

She goes on to trace the evolution of the I in a long progression of writers—from Tolstoy and Dostoevsky through Céline, Gide, Svevo, and Proust—for whom the I “no longer resides in the story, but rather now the story resides in the I.” The culmination of this transformation, Bachmann says, can be seen in Samuel Beckett’s novel The Unnamable (1953), where the I at last is completely dissolved in the “liquidation of content as such.” Much like the amorphous narrator of Malina, who is often referred to as the “I-figure” in critical discussions, Beckett’s narrator, Mahood, is reduced to a head, torso, arm, and leg; his sole raison d’etre is to think and to question. Yet even though “Beckett’s I loses itself in a mumble,” Bachmann notes, “the urge to talk persists nevertheless; resignation is impossible”—and she ends on a note of affirmation for this “I without guarantee,” this “placeholder for the human voice.” (In her fourth lecture, the weakest of the five, Bachmann fittingly takes up the “imperilment” and “atrophying” of names in literature, from Kafka and Joyce to Faulkner, whose “method” in The Sound and the Fury, she writes, is “to divert us from names in order to thrust us straight into reality without any explanation. . . . we have to do our best to see—as in reality—how far we can progress . . . among people whom no one fashions for us in advance.”)

Bachmann’s fifth and final Frankfurt Lecture, “Literature as Utopia,” is her best known, and for good reason. Despite her anxious striving against inadequate language, Bachmann never stopped believing in the regenerative potential of literature, and here she locates its power precisely in its lack of “closure,” in its being “open-ended” with “unknown boundaries,” its refusal of “objective judgment” and “final consensus and classification.” In bold strokes for the time, Bachmann firmly dismisses scholarly efforts at timeless canonization, viewing the texts of the past as sources for continual and inevitable reinterpretation and as catalysts for our own “enthusiasm for the blank page.” Rather than seek definite criteria by which to circumscribe “literature” once and for all, Bachmann instead offers a sort of Wittgensteinian conclusion—that literature makes itself manifest in a striving to say what hasn’t yet been said:

Literature, which is itself unable to say what it is and only reveals itself as a thousand-fold and multi-millennial infraction against flawed language—for life has only a flawed language—and which therefore confronts flawed language with a utopia; this literature, then, however closely it might cling to the time period and its flawed language, must be praised for desperately and incessantly striving toward the utopia of language. Only for that reason is it a source of splendor and hope for humankind. Its most vulgar languages and its most pretentious ones still share in a dream of language; every word, every syntax, every period, punctuation, metaphor, and symbol redeem something of our dream of expression, a dream that is never entirely to be realized.

“War is no longer declared / but rather continued,” Bachmann had written in “Every Day,” a poem from her first volume, and one war she came to see as perpetual was the one with “flawed language.” More than a decade before Hannah Arendt famously spoke of the “clichés, stock phrases” and “adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct” that “have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality,” Bachmann decried the everyday language that conceals “where we stand or where we should be standing” and sought a new one adequate “to ourselves and the world.”

The devil’s ploy faced by any artist is the folly of perfecting the life while attempting to perfect the work. Plagued by dead ends in love, Bachmann hardly had illusions of the former. Following her disastrous relationship with Frisch, Bachmann suffered a breakdown in 1962 and was hospitalized for a year after a suicide attempt. Struggles with alcohol and prescription drugs continued until her death. Bachmann, however, did not covet suffering as a resource for her work. “There is nothing poetic about illness, and the great invalids, from Dostoevsky to Sylvia Plath, know that,” she wrote.

Instead, what Bachmann valued was the necessity of art to give expression to suffering in order that it be faced and addressed. She ends her final Frankfurt lecture by quoting antifascist poet René Char, who led a unit of the French Resistance. “To each collapse of proofs the poet responds by a salvo of the future,” he wrote in 1944 under Nazi occupation. For Bachmann it was much the same. The Critical Writings remind us that Bachmann’s utopian pursuit, though cut short, aimed for so much more—and that amid the collapse of proofs in our own day, the salvo of the future remains ours to write.

Independent and nonprofit, Boston Review relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate or become a member.