The State

Philip Pettit

Princeton University Press, $39.95 (cloth)

The Project-State and Its Rivals: A New History of the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Charles S. Maier

Harvard University Press, $45 (cloth)

The Life and Death of States: Central Europe and the Transformation of Modern Sovereignty

Natasha Wheatley

Princeton University Press, $45 (cloth)

In early 2022, the Economist decried “governments’ widespread new fondness for interventionism.” The state was “becoming bossier” and “more meddlesome,” it complained. In fact, the state’s punitive arm was plenty active in the United States and the United Kingdom during the decades that neoliberalism shredded public investment and public goods, to say nothing of the foreign interventions of these states over this period. But on the economic front, at least, the Economist was right: state spending and regulation are back after years of retrenchment.

In the United States, the federal government has recently spent $5 trillion under two presidents to act against public health and economic threats, and the Biden administration is boastfully pursuing “industrial policy” to remedy problems created by four decades of deference to the private sector, especially around climate. Add to this a more aggressive approach to antitrust enforcement and regulation in general, and the administrative and development elements of today’s American state looks very different than they did in 1990 or even 2010. This new statism is a direct response to the rise of China as well as a rejection of the anemic policies rolled out to combat the 2008 financial crisis. Many left-of-center officials and policy intellectuals have concluded that both national security and the preservation of democracy against populist threats require more vigorous government control over markets.

The return of (this arm of) the state isn’t just the dream of many on the left; some quarters of the American right have shown interest as well. Of course, conservatives have long used the state to punish perceived deviance, but Donald Trump and his allies on the New Right are in some ways ditching the GOP’s free market hymnbook—at least rhetorically. To a growing if still small faction of Republicans such as Marco Rubio and Oren Cass, shrinking the state “down to the size where we can drown it in the bathtub,” as Grover Norquist promised, is out of fashion; taking the reins of a powerful state—and harnessing it for trade wars, industrial policy, or even a more generous welfare state—is in.

And it’s not just the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a massive increase in state intervention around the world as governments pumped their economies full of cash and undertook public health measures—“among history’s largest exercises in state power,” in historian Peter Baldwin’s analysis. China’s zero-COVID interventions were perhaps the most dramatic example. Xi Jinping has also reversed a three-decade trend toward decentralization, using the state to support allies and key industries, promote an anti-inequality “Common Prosperity” agenda, and crack down on independent sources of power. Russia, for its part, has turned to the state to mobilize the Russian economy and society into a war machine, while the European Union is easing off ordoliberalism to promote a green agenda with carbon tariffs and has even taken steps toward becoming more state-like, issuing common debt for the first time during the pandemic.

In light of these developments, it is perhaps no surprise that the state is the object of renewed scholarly attention. Three recent books demonstrate its place in ongoing intellectual debates. In The State, philosopher Philip Pettit exhorts political theory to return to classic questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of state power. In The Project-State and Its Rivals, historian Charles Maier gives a sweeping analysis of one particularly activist form of the modern state. And in The Life and Death of States, historian Natasha Wheatley recovers alternatives to prevailing ideas about state sovereignty through the lens of the Habsburg Empire. Together these works help illuminate the stakes of our new statist age, along with its possible limitations. Renewed control over capital is a welcome development, but can the revitalized state rise to today’s challenges—perhaps most urgently, climate change?

A major aim of Pettit’s book is to place the state back at the center of political philosophy. Following the publication of John Rawls’s monumental A Theory of Justice (1971), he laments, the state took a back seat to debates about justice. He makes a case for linking these concerns, in part, by arguing that the state is necessary for justice. And he further justifies his focus on the state with a dose of “realism”: as a political form, he thinks, it is simply “destined to survive”—so it is essential to have a theory of the nature of the state and the function it must play in the lives of citizens.

One element of such a theory asks, just what is a state? Pettit offers a functional account. Polities count as states, he argues, when they fulfill its central function: “individually securing its citizens against one another under a regime of law that it safeguards against internal and external dangers.” By establishing and enforcing “a coercive, territorial regime of law” and protecting itself from enemies foreign and domestic, the “fully functional state” provides “each citizen a reliable, determinate zone of legal security, however limited it may be, within which they can decide on how they want to live their lives.”

This is a fairly minimal view of the state—not exactly resonant, at first blush, with the ambitions of today’s neostatists in the Biden administration. It reflects Pettit’s career as an interpreter and exponent of “neo-republicanism”—a tradition of political thought that focuses on liberty. As Pettit has developed it, republican liberty is a condition of non-domination, meaning that individuals are not subject to unchecked power. To be in a position of non-domination “is just to be in a position where no one can interfere arbitrarily in your affairs,” Pettit explains in Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government (1997). With The State, he provides “a prologue to a neo-republican theory of justice,” detailing his vision of the state as the institution capable of nurturing justice and preventing domination.

The functional state that Pettit sketches shies away from extremes and aims for a sense of balance. “Moderation” is one of the book’s key words. For Pettit, the moderate state avoids the pitfalls that concern three prominent political approaches. First, despite the fears of Thomas Hobbes and other proponents of an “absolutist form of statism,” the state does not necessarily curtail opportunities for its citizens to generate “collective, countervailing power.” Second, the anxieties of “radical” libertarians notwithstanding, the state can “recognize and honor” significant individual rights. And third, against the tut-tutting of laissez-faire theorists, the state “will have the capacity to intervene productively in the market economy.” Drawing on the empirical work of Karl Polanyi and Katharina Pistor, Pettit argues that since the market economy is not independent from the state (as laissez-faire theorists believe), “modern pressures”—from citizens and financial interests—“would force” any functional state to take interventionist measures.

In other words, Pettit’s state—which in the end looks strikingly similar to the modern, liberal state—seeks to steer between the Scylla of a maximal state and the Charybdis of Norquist’s bathtub. This solution may seem obvious enough, and many would likely embrace it. The most important condition of balance, Pettit maintains, is the “balance of power between rulers and ruled.” Any benefits that the state might deliver can only be actualized when “there is a rough balance of power between rulers and their subjects.” It is precisely the condition of equipoise that prevents the domination of “decision takers” by “decision makers.” This balance of power is so central to Pettit’s analysis that without it a polity is not even considered a state; polities that are too powerful or too powerless are actually “failed or failing counterparts.” “If they still count as states,” Pettit writes, “that is only in the sense in which the heart that has ceased to pump blood is still a heart.” On this view, the state is not just a tool for moderation but constituted by moderation.

For all this focus on balance within states, however, Pettit pays no heed to balance among states. The international system is practically defined by the power of great power “decision makers” over everyone else. Pettit would likely say, correctly, that there isn’t a world state, so of course a dog-eat-dog dynamic prevails. But if the domestic decision makers in nearly every polity are ultimately decision takers at the international scale, is the state as he defines it really a major actor in world politics? In fact, even the statehood of the United States is in question on Pettit’s account. Examined through the lenses of the power of the wealthy over policy or the power of the police over many communities, the U.S. state—though hegemonic on the global stage—starts to look like a “heart that has ceased to pump.” Pettit shies away from such a judgment, but his argument suggests a sense in which Americans might be construed as stateless—or at least members of a “failed or failing counterpart,” for whom a significant reconstruction of the polity is in order.

Despite Pettit’s attempt to recover a tradition of inquiry that Rawlsian concerns with justice have displaced, The State resembles A Theory of Justice in focusing on ideal theory; it contains little history or sociology of the state, or politics for that matter. Theoretical arguments may be helpful so far as they go, especially in setting goals and in the work of public reasoning—that is, in justifying state action to citizens. But both state power and the pursuit of justice are ultimately practical matters, and even if we all agreed on the desirability of Pettit’s state, we would need a strategy for building it. As Thad Williamson recently put it in these pages, ideal theories of “what a hypothetical good society would look like” generally neglect “the process by which we might get there.”

Rather than positing an intrinsic, ahistorical relationship between justice and the state, what can we learn by viewing the pursuit of justice as one of the state’s “projects” that emerged over the twentieth century?

Maier’s book gives us the conceptual language to think about this historical development. He zooms in on the “rise and eclipse” of a particular state form he calls the “project-state,” a twentieth-century activist state committed to a “transformative agenda” and “that consciously aspired to inflect the course of history.”

For Maier, the category is expansive and morally neutral: it includes New Deal America and Germany under Hitler, the postwar British welfare state and China under Mao’s Great Leap Forward. As Maier puts it, “project-states have served as a force for good and for evil.” The defining characteristic of the project-state is that it sought “not merely to govern day to day” but “aspired to change social and economic relations in a profound way.” Its raison d’être was “to transform the nonpolitical institutions of society—economic outcomes, public health, religious commitments and secular loyalties, landscapes and cityscapes.”

The rise of the project-state ushered in a sea change in political arrangements. For much of the early history of modern states—when monarchies and divine right reigned—there was simply no intellectual or moral framework to suggest it was the state’s role, or even within the state’s abilities, to improve the lives of the many. This attitude was displaced over the course of the nineteenth century, as Maier (and many others) have charted. Transformations in scientific, social, and political thought introduced both the idea of progress and the idea that the state could intervene to promote progress in society. At the same time, new technologies and administrative techniques created the capacity for the state to act at scale in society. The invention of the railroad, steam-powered boat, and telegraph, Maier argued in a previous book, “let extensive territories be governed . . . in real time: they conveyed the sense that national space was a realm of relatively simultaneous application of control.” No longer solely focused on the benefits to the ruling dynasty and in possession of a new intellectual and technological toolkit, nineteenth-century states, observed the sociologist Charles Tilly, “involved themselves much more heavily than before in building social infrastructure, in providing services, in regulating economic activity, in controlling population movements, and in assuring citizens’ welfare.”

Indeed, many state functions that we now expect—and that are central to Pettit’s account—first emerged in this era. Modern policing, including the idea of a dedicated, professional police force, was established in Britain in 1829. Modern government social statistics began to be collected in large quantities in the 1830s and 1840s. Modern public health developed in response to advances in science and medicine, such as Louis Pasteur’s discoveries on the germ theory of diseases in the 1850s and John Snow’s famous map of the London cholera outbreak in 1854. Modern border controls, including the introduction of the passport, began to be implemented, though borders remained much more porous until the Great War. Bismarck’s passage, in 1883, of state-based health insurance for workers in Germany heralded the arrival of the modern welfare state.

These nineteenth-century projects were merely the foothills of the project-states that constitute what Maier calls “the Himalayas of twentieth-century history.” The strength of his book is that it situates these towering state-led ambitions to form, inspire, reform, and reinspire a population alongside three additional “protagonists” of history. One is resource empires, which were built to be “cash cows for beneficiaries in the metropole or settlers in place” so that they could “enjoy the fruits of overseas colonies.” The other two were territorially unbound “organizations and networks that aspired not to sovereign power but to moral and political influence and/or to material gain”—specifically, transnational domains of governance and of capital.

By governance, Maier means the web of “nonstate or interstate organizations that proposed to intervene in society by invoking ethical, normative, or ‘expert’ considerations.” This network of transnational activists sought to build “a society of values” through an incredible range of institutions: the League of Nations and United Nations; the global envelop of international law and the bevy of organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International that seek to hold states to its standards; bodies that promote cross-national technical standards and scientific collaboration such as the International Telecommunication Union, International Science Council, and International Rice Research Institute; and a wide range of NGOs, from the Ford Foundation to Oxfam to the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Where Maier takes a neutral view of project-states, he is more positive about governance. “I tend to believe that institutions of governance play a generally beneficial role and deserve the authority they claim,” he writes. The point is not totally convincing. If project-states can “construct the Tennessee Valley Authority on one hand and Auschwitz on the other hand,” why do we “not usually refer to the governance of the Mafia or the Zetas”? What is the Islamic State if not a transnational organization trying to construct “a society of values”?

The realm of capital certainly made no pretense of its moral commitments. For Maier, it “has included the individuals and organizations—firms, banks, trade associations—that participated in markets, where they reciprocally exchanged goods, labor, real property, and promises of future payments in a framework supposedly free of legal or extralegal coercion.” Throughout the book, these economic agents work to increase their profits in a world defined by shifting relations between themselves and the other three protagonists. Much of the narrative charts the actions of the energy industry—first coal, then oil—to secure its place among other political, economic, and ideological forces. These forces, particularly those of the state, were at times energy’s staunch ally, but at other times they acted to rein in the sector’s power.

This points to Maier’s true ambition: to plot “the changing balance among the protagonists of the twentieth century.” His history is one of relations. It seeks to explain the structure of world history by charting how project-states, resource empires, governance institutions, and the globalizing web of capital vied for power. Over time, the balance of these forces changed. In the three decades after World War II the project-state “beckoned with a renewed luster” and took on an “expanded role” while “agendas for governance and projects for capital remained overshadowed under state or interstate umbrellas.” Yet by the late 1960s and 1970s, capital and governance began to reassert their power over a diminishing national state.

This story of the exhaustion of the postwar political-economic order has now been told many times; what sets Maier’s account apart is the way he weaves together the work of capitalist activists and their allies in politics and think tanks with the work of governance activists in the same years. His wide-angle lens shows how the political and economic turbulence of that period led not only to the Volcker shock but to the rising prominence of NGOs and foundations seeking to restore order and stability at home and abroad.

As historian Samuel Moyn has shown, human rights—one node in the web of governance—emerged precisely in the 1970s following the floundering of state-led capitalist, socialist, and nationalist projects. What’s more, Moyn argues, it is no accident that the rise of human rights coincided with the rise of economic inequality. The projects to roll back the state’s use of fiscal authority and regulation and to roll back the state’s use of torture and political imprisonment shared similar impulses and dynamics. At several points, Maier argues that neoliberal rollback of the postwar project-state’s accomplishments—key among them taming capital and building the welfare state—was “an alternative state project in its own right.” On this score, he echoes Quinn Slobodian’s argument in Globalists (2019), suggesting another weakness of the Economist’s flat talk of “the state” having returned—a claim that assumes it had actually disappeared. In reality, neoliberals didn’t abandon state power; they redirected it for their own ends.

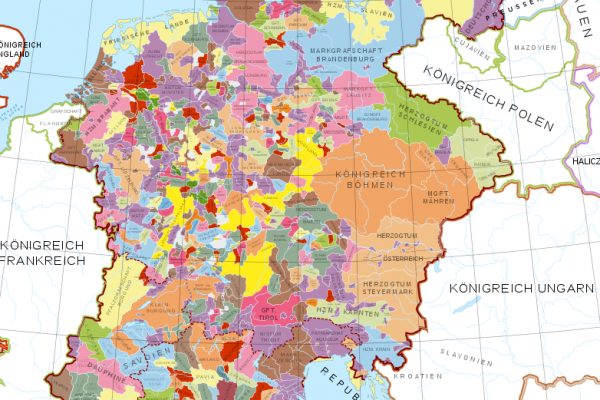

Before states can take on projects they must first exist. But when, exactly, is a state born? The successors to the Austro-Hungarian Empire have often been held up as an easy case. According to a familiar story, these states sprung fully formed from the minds of nationalist statesmen immediately after the demise of the Habsburg monarchy. Wheatley shows that real story of the birth, life, and death of states in Central Europe is much more complex.

One reason the true history is messier than often supposed, she demonstrates, is that many of the central political actors in the era claimed that these states couldn’t be born at this moment—because they were already alive. Austria-Hungary was an “intricately layered, prodigiously complex empire,” she stresses, one that had accrued its territories over many centuries by absorbing many formerly distinct legal entities. As the empire crumbled in 1918, politicians and others aspiring for national autonomy or independence in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and elsewhere argued that these old legal jurisdictions—“their original legal standing, their original independence”—“had survived long centuries of imperial rule intact.” Their ancient polities, they claimed, had been “swallowed up but not dissolved in the python of empire.” As Georg Jellinek, a Viennese jurist at the center of Wheatley’s study, argued in 1900, the territorial expansion of the empire “was not accompanied by an explicit declaration of the de-state-ification of its parts.” “The moment at which the Bohemian lands entirely lost their state character cannot be determined with complete certainty,” he maintained.

Czechs and Hungarians especially relied on this theory of statehood when pressing for independence after World War I. As the Hungarian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference claimed,

Hungary is no new State born of the dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. . . . As far as public law the Hungary of to-day is the same State she has been through her past of a thousand years. She kept her position as an independent State on entering a union with Austria and during the whole existence of this union.

This view had several advantages for advocates. It not only spared them the trouble of establishing “new” states; Wheatley demonstrates that it also allowed nationalist activists to claim the legality and legitimacy of the Habsburg empire itself—since the leaders were respecting the imperial legal framework that had tenderly preserved their beloved frozen kingdoms for so long.

The most difficult questions, Wheatley shows, pertained to the birth of Austria. With the Settlement of 1867, the empire was divided in two halves, each fully and equally sovereign. The eastern half was easily identifiable: the Kingdom on Hungary. The western half had a more ambiguous identity: it was known formally as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Parliament, less formally as Cisleithania (because it was on “this side” of the Leitha River; Hungary being on the other), and informally (but incorrectly) as Austria. When the empire fell apart, it was not clear what was to be done with this territorial rump. “German Austria,” observed Austromarxist intellectual and politician Otto Bauer in 1923, “is nothing but the reminder that was left over from the old empire when the other nations fell away from it.” (Visitors to grand, gilded Vienna may still feel this way while strolling the Ringstrasse.) In the end, it was the Allied powers that christened the territory the “Republic of Austria.”

Naming the country was the least of the worries, however. The real issues concerned legal continuity: Which country was the legal successor to the Habsburg Empire? The leaders of the new Austrian Republic were emphatic that it wasn’t them. “The Danube Monarchy,” the Austrian chancellor explained to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, “ceased to exist on 12. November, 1918.” Everything that happened before, Austrian diplomats argued, “has no more upon German-Austria than on Czecho-Slovakia or any other national State which has arisen on Austrian-Hungarian soil.”

In all these cases, abstract questions of theory became very concrete. “Political events of the present,” as one Austrian jurist put it in 1919, “present various problems of legal science that, until now, were only objects of theoretical investigation.” These “political events,” moreover, created legal problems of grave concern to ordinary citizens, not just politicians and lawyers. The end of the Habsburg Empire and formation of new nation-states left many thousands of people legally stateless citizens of nowhere.

In her recent book Statelessness (2020), historian Mira Siegelberg traces how formerly Austro-Hungarian and Russian thinkers approached the problem of statelessness after World War I in ways that opened new democratic and cosmopolitan possibilities, including designs for robust international organizations and visions of just world orders. (This was before the even greater crisis of statelessness after World War II contributed to the foreclosure of these possibilities and helped solidify the hegemony of the nation-state as “the sole legitimate organizing unit of global politics,” as Siegelberg puts it.) But on the ground, those whose imperial passports were abruptly made meaningless experienced the life-upending consequences of state death.

With wars raging in Gaza and Ukraine, concrete questions of state birth and state death are back in the news. A longer-term worry stems from rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and many other consequences of a warming planet. What will happen to the states of Nauru and Kiribati if their territories sink beneath the waves? How will states cope with climate-induced migration? More proactively, can states cooperate to drive global carbon emissions to zero? The problems that climate change poses for statehood may be exceeded only by the problems that statehood poses for the possibility of a habitable planet.

This fact is reflected very differently in these three books. Pettit, for his part, mentions climate change just twice. He first identifies it as one of a small number of catastrophes that could cause the state to be “disrupted or undone” as a political form, and then he suggests that future human flourishing rests on “how states perform” when faced with “climate change, pandemic threat, chronic deprivation, and the eruptions of inhumanity that seem to come with our genes.” Hard to disagree there.

Maier says more. On the one hand, he identifies climate change as a major cause of the contemporary world’s “sense of untethering,” and he notes that the project-state itself was a major cause of skyrocketing greenhouse gases during the postwar “Great Acceleration” of carbon-fueled growth. On the other hand, his narrative suggests that a strong state—with a “transformative agenda”—offers a potential solution.

It might seem that Maier is headed to an embrace of the Green New Deal state. In fact, he comes to a different conclusion: “Perhaps the individual project-state should no longer suffice as an aspiration but given the scale of the global challenges must ultimately form part of an international society.” Given the book’s focus on global networks of capital and governance, it is may not be surprising that Maier finds the state both limited and limiting. The scale of governance must match the scale of the problems, he suggests. But though he approvingly gestures to mid-twentieth century visions for new models of statehood and international order, he doesn’t mention that in every single case they failed.

A major factor in each failure was the allure of sovereignty, which still stands in the way of international “projects” today. Take the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the 1992 treaty that established the international architecture for tackling global warming. Its signatories echo Maier’s argument, acknowledging that a changing climate is “a common concern of humankind” and that “the global nature of climate change calls for the widest possible cooperation by all countries . . . and appropriate international response.” But then the treaty snaps back to form, explicitly reaffirming “the principle of sovereignty of States” and “the sovereign right [of states] to exploit their own resources.” If we hope for “international society” to come to the rescue, we are going to need a new approach to sovereignty.

This observation isn’t new; sovereignty has long been the bugbear of those who hope for greater global cooperation. Already in 1934, legal philosopher Hans Kelsen—a student-turned-rival of Jellinek, and also one of Wheatley’s central characters—condemned “the ossifying absolutism of the dogma of sovereignty.” In its place, he sought to develop a new theory that “relativizes the state” and places it in a “continuous sequence of legal structures, gradually merging into one another.”

This is a radically different vision than the dogma enshrined in international law and politics today, which rests on “the singularity of sovereignty,” as Wheatley observes: “the notion of a single, supreme, undivided power.” Habsburg thinkers didn’t recognize their world in this model, developed by English and French thinkers. Instead they sought a sovereignty that rang true to their “layer cake” of a polity—a state structure that Pettit, without citing its most important contemporary theorist Elinor Ostrom, calls “polycentric.” Theorizing from the center of Europe, these thinkers found that sovereignty came in many hues and gradations; it wasn’t black and white. Wheatley’s recovery of their work makes clear that “neither ‘state’ nor ‘sovereignty’ can be taken as fixed, pregiven things.” New concepts and theories in hand, Habsburg theorists imagined new forms of national and international order.

The unmooring of absolutist concepts of the state and sovereignty could be useful for new governance projects at the scale of the challenges we face. Deploying Habsburgian tools, rather than Anglo-French ones, we might imagine a planetary project-state that avoids becoming the “climate leviathan” that Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann have depicted—a “coherent planetary sovereign” that absorbs, countermands, or otherwise annihilates the sovereignty of all existing states. Wheatley notes that as Jellinek saw it, “the defining characteristic of a sovereign state was that it could be bound only by itself. . . . Precisely because a sovereign state had unlimited final authority over itself, it could decide to bind itself to another and give up some of its rights.” On this view, it is confidence in the strength and legitimacy your own sovereignty that permits modifications to it.

Wheatley gives a striking example of such sovereign self-assurance. In 1904, Hungarian statesman Count Albert Apponyi gave a lecture attacking the “widespread fundamental error” that considers the “Austrian empire . . . the primoradial fact, and whatever is known of Hungarian independence as a sort of provincial autonomy.” He explained:

The primordial fact is an independent kingdom of Hungary, which has allied itself for certain purposes and under certain conditions to the equally independent and distinct empire of Austria, by an act of sovereign free will, without having ever abdicated the smallest particle of its sovereignty as an independent nation, though it has consented to exercise a small part of its governmental functions through executive organs common with Austria.

Arguments of this sort illustrate how international cooperation need not be perceived as coming at the expense of national sovereignty. And indeed, this attitude is evident in the rhetoric of actually existing international cooperation—including the UNFCCC and the UN Charter itself.

There is a flip side to this reasoning, of course. Ceding one’s sovereignty is difficult when it is not felt to be secure. This fact helps to explain why, of all the multinational federated political structures proposed or tried in the decades after World War II, the only one to survive was the European Economic Community and its successors. The wealthy and well-established states of Europe, not the poor and inchoate states of the postcolonial world, were willing to voluntarily abrogate their own sovereignty in order to facilitate “common action” toward “economic and social progress,” in the words of the 1957 Treaty of Rome.

In a world still marked by grave power imbalances, overcoming these obstacles will not be easy. But we should not consider it impossible. Efforts to shift the balance of global power away from the U.S.-led “liberal international order” are afoot, from China’s Belt and Road Initiative to the recent expansion of the BRICS+ bloc. And renewed interest in the Group of 77’s 1974 proposal for a “New International Economic Order,” a largely forgotten episode in the global struggle for justice, may offer a “usable past” from which new political projects can be launched.

There is much creative thinking to be done. Like the Habsburg jurists who watched their imperial home collapse, we—all citizens of an overheating, interconnected planet—are at a critical juncture. Wheatley draws on political theorist Adom Getachew’s work on “worldmaking after empire” in the Black Atlantic to argue that “the bracing experience of new statehood made questions of international order existential and drove new theories and projects at the scale of the world.” The challenge of climate change demands similar thinking today. Whether the state is a part of our collective future—or whether it gives way to alternative forms of sovereignty and instruments of rule—is, as Maier puts it, “up for grabs.”

Boston Review is nonprofit, paywall-free, and reader-funded. To support work like this, please donate here.