The first time I ever heard of Richard Yates, I was sitting at the round table in the back of Ski's Drive-Inn in Kingsville, Texas, on a late Saturday afternoon. Ski's was the sort of place frequented by off-shift roughnecks, road crews, working cowboys, and whatever college students felt at home there. During my years at Texas A & I, whenever I couldn't find a morning tower job on a drilling rig, Ski would let me work at the Drive-Inn hopping tables, stocking beer, and working out the duty roster for the gang of wild girls—mostly Navy wives dumped at the nearby base—until I found a rig. I was at the end of two weeks of cutting brush across an overgrown pasture for a waterline, two weeks of brush hogs, grubbing hoes, and double-bit axes, all to raise a little travel money for the move to Iowa City where I intended to become a rich and famous writer.

Halfway into my second burger and pitcher of Lone Star, Bill Harrison came in to join me, cool and professorial in a polo shirt and khakis. Bill had been the writing teacher who convinced me to give up my notions of a Ph.D. in Soviet history and give this writer thing a chance. He handed me a paperback copy of Revolutionary Road. "Richard Yates is going to be teaching at the Workshop this year," he said. "You should get to know him. He's a real writer." I stuck the paperback into the sweaty back pocket of my jeans, a pocket lined with mesquite chips, cat-claw brambles, and black land dust. I told Bill Harrison goodbye, then went back out to the job, chopping and grubbing and burning brush.

During the trip to Iowa City, I read Revolutionary Road at night in cheap motels from Midlothian, Texas, to Marengo, Iowa. I had only been to one play in my life, something starring Diana Dors, hadn't had a literary domestic argument with my wife, though that was coming shortly, and couldn't see the connections between a Connecticut suburbanite and redneck, Bordertown trash like me. My people never felt guilty about hangovers. Hell, we gloried in them. But I wasn't thinking much about these things as I hurried north toward a new life, my old Renault pulling a tiny trailer stuffed with a refrigerator, four boxes of books, a chest of drawers, and all of our wedding gifts from a couple of years before when I had been a physics major. Somewhere in the Arbuckle Mountains of Oklahoma, I glanced at my wristwatch. I'd always hated wristwatches. Hell, a writer wouldn't need a wristwatch. So I threw it out of the car window, then began to learn about that literary domestic disagreement.

Because my wife had a job teaching school in a junior high out in Oxford, we got to town a few weeks earlier than the rest of the students. I quickly found a job tending bar at Joe's Place, and the only other person I knew in Iowa City, Bob Lacy, also had a late-night job at the student paper, so we wandered the collegiate streets of Iowa City, trailing the fragrances of warm pizza and cold beer, arguing about books and planning our lives. One thing we knew about the near future, though. We were not going to endure any of the English courses newly required by the Workshop. We hadn't come to Iowa for these courses, and the head hogs had only decided that they would be required while we were on the road from Texas. We were going to sign up for Richard Yates's modern novel seminar. To Hell with the academic road.

An army may march on its stomach, but a bureaucracy shuffles on its paper. I had already shuffled my way into graduate school nine hours short of an undergraduate degree. Getting us out of a regular English department class and into a full seminar was child's play. And certainly worth the effort.

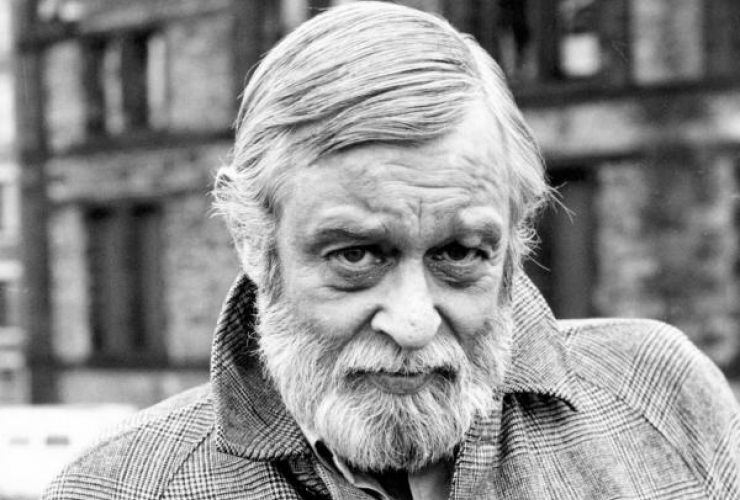

Even swathed in his armor from Brooks Brothers, Dick Yates moved around a classroom like a true gentleman, but one about to be executed, dodging this way with a hoarse cough, back with a husky chuckle. I don't remember anything he said that day, just the way he said it with shyness akin to a holy truth. I don't even remember what his opinions were, much, except that he thought All the Kings Men a fake novel and at the end of the seminar tossed his copy into the wastebasket.

When that first class was over, Dick stretched out his arms, and said, a wistful but charming grin lopsided on his face, "Hey, I'm going up to the Airliner for a martini. Anybody want to go along?"

I knew I was sitting in a room filled with the graduates of some of the best universities in America, but nobody answered. After a few seconds, though, I stood up, and said, "Hell, I'll go."

So Dick and I wandered out of the sheep sheds, across the street to the parking garage, so we could take the elevator up the hill. Then we strolled like masters of the world to the Airliner, where I had my first martini, and Dick and I became friends. He wondered why my name wasn't on his class list, and I explained when it was coming and how. He found that amusing, then when I told him how I had bluffed my way into graduate school, he laughed so hard he started coughing. That was my first notion that this wasn't just a cigarette cough. We drank martinis until I had to go behind the stick at Joe's Place.

Over the academic year that followed, Dick and I saw a lot of each other, seemed to go to the same parties, to have the same friends: Andre Dubus, Bob Lacy, Verlin Cassill, Lori Miller, Kenny Rosen, Roger Rath, Ted Weeser, and dozens of others whose names have slipped down the loose ribbons of time. I rereadRevolutionary Road and read the stories for the first time. I began to understand another way to look at the world. It's impossible to write a scene of hopelessly sad domestic disorder without thinking of Frank and April Wheeler. Dick read a couple of my early stories, though he had little to say, just scratched his head, and suggested a rewrite.

But the most important thing he did for me that year was to accept me as a friend and a writer. His going-away party started in the afternoon, and I was around for the beginning, but I had to leave for a four-hour shift at my janitor's job. When I finished, I went to our apartment to clean up and go back to the party. My wife didn't want to go—she'd never really adjusted to living in Iowa City or the fact that I seemed to go crazy after I finished a new story or found another woman I should have married—and she didn't want me to go either. And she was willing to fight about it. Who could blame her? So I cracked a beer and turned on the television. Five minutes later the telephone rang. When I picked it up, a smoky voice rasped at me, "Goddamnit, Crumley, where the hell are you?"

I was out the door.

It seems to me the last time I saw Richard Yates was at a party at Andre Dubus's in the late 1970s. Dick was deadly gray and deeply hunched by then. Only the rough weave of the Brothers Brooks seemed to keep him upright. But nothing could keep him down. He squinted sideways across Andre's kitchen table, waving his cigarette at our jeans and cowboy belt buckles, growling, "Aren't you guys ever going to start wearing grown-up clothes?"

Not like you, Dick, not like you.