On the 18th December he got me in the storeroom, and asked me to sew a button on his trousers. He asked me to go in, and I went in, and whilst I was threading the needle he began to use dirty language, and also behaved indecently.

Gretchen Carlson was not the first woman to be sexually harassed by her boss. Rose McGowan was not the first to keep her mouth shut in terror. The anecdote above, from a nineteenth century British garment worker, suggests that harassment is as old as workplaces with men in charge—to say nothing of slavery and household service. Sexual harassment, in other words, is as old and as wide as work itself.

Cornell University professor Lin Farley coined the term “sexual harassment” in the 1970s. Before that its names were euphemistic or misleading: “moral outrage,” “improper purposes,” “dirty tricks,” “seduction.” But from mill girls to models, chicken-pluckers to paralegals, victims have known it when they felt it.

Sexual assault is more than men doing bad things to women. These men are embodiments of capital, using its power not just against some women, but against women as workers.

These women also knew they risked shaming, firing, or deportation if they reported their experiences. If they were tarred as troublemakers, they could be blackballed; if they were chosen as (provisional) favorites, they could be extorted. So for most, silence was, and is, the rational strategy. But it was not precisely true, as National Organization for Women (NOW) President Karen DeCrow told the New York City Commission on Human Rights in 1975, that sexual harassment was “one of the few sexist issues which has been totally in the closet.”

In fact, narratives such as the above can be found in newspapers, government reports, court transcripts, union records, memoirs, and novels. In The Jungle (1906) Upton Sinclair decried “unspeakable” sexual coercion in Chicago’s meatpacking plants. Emile Zola exposed the same in department stores and coal towns. What reader can forget the image in Germinal (1885) of striking miners’ wives brandishing on a spike the penis of a shopkeeper who demanded sex for food? The words of nineteenth and early twentieth century British and U.S. cotton-industry and garment workers sound eerily familiar:

Lately the light in the passage has developed a habit of going out when a young woman has been walking alone. Women who have had that experience state that, in the dark, an arm has been placed round their waist, and worse things have followed.

I felt what that glance in his eyes meant. It was quiet in the shop, everybody had left, even the foreman. There in the office I sat on a chair, the boss stood near me with my pay in his hand, speaking to me in a velvety, soft voice. Alas! Nobody around. I sat trembling with fear.

So why are we still dealing with this one hundred and fifty years after the Industrial Revolution and fifty years since second-wave feminists revived sexual harassment as a political issue?

Here’s a theory: sexual harassment happens to women (and sexual and gender minorities) at work. It is intersectional, a case of economic and gender oppression. But progress is uneven. As women become more equal as women, their rights and the power of the institutions that represent them as workers are progressively being overtaken by the prerogatives of employers and corporations. The result: it is every woman for herself, which means only a few women prevail.

As women become more equal as women, their rights are overtaken by employers. The result: it is every woman for herself, which means only a few women prevail.

In spite of backlash, feminism has marched steadily forward over the last forty years, changing both consciousness and the law. One indication is the simple fact that this time around men are not dismissing women’s grievances as ridiculous, exaggerated, or funny. In a recent Washington Post-ABC poll 64 percent of respondents believed that sexual harassment is a serious problem.

As Elizabeth Bruenig pointed out in the Washington Post, some of the accused plead that they’re just old-fashioned guys, brought up during the Sexual Revolution. But “exorbitant sums of hush money, clandestine notes, private hotel rooms and careful victim scouting . . . are not the precautions of heedless old-timers. They’re the triangulations of people who know they’re doing something wrong and want to get away with it.”

Meanwhile, after being ignored as pussy-whipped outliers, pro-feminist, anti-violence men have the floor. Former enablers such as Quentin Tarantino are publicly atoning. Odd cross-gender alliances are forming—Joe Biden and Lady Gaga tweeting together, “It’s on us.”

Women have won advances in the law, as well; since its passage in 1964, amendments to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act clarify that sexual harassment is illegal. There is, of course, progress to be made. Unlike discrimination based on pregnancy or disability, for instance, no federal law specifically addresses harassment, and fewer than half of claims to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission result in charges.

Still, on the whole and as a sex, women are trudging uphill. Workers, on the other hand, are sliding down, crushed under an avalanche of anti-labor legislation and corporate-friendly court rulings.

As women’s presence in the labor force has grown, union membership has fallen. From the Great Depression through World War II membership surged, reaching a peak of 35 percent in the mid-1950s. By 1983, it was down to just over 20 percent, and by 2016 halved again, to 10.7 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. At the same time, right-to-work laws and reforms such as Wisconsin’s Republican-backed Act 10 have chipped away at bargaining rights and the mechanisms unions use to collect dues, such as automatic payroll deductions. Unions have less room to organize and win raises, benefits, and better conditions for their members and fewer resources to effect worker-protective legislation and pursue legal action.

This hurts everyone. Contrary to beliefs that union members constitute an aristocracy floating above and away from the sweated masses, union gains lift many more boats. By the same token, the Economic Policy Institute reports, foundering unions are an “overlooked reason” that middle-class wages have stagnated since 1979.

Since the demise of organized labor, women became personally stronger and effectively weaker.

The demise of organized labor is both a cause and a result of the “gig economy,” in which millions of digital nomads, contract workers, freelancers, adjuncts, and odd jobbers toil more and more for less and less. According to the Federal Reserve, Millennials earn 20 percent less than Baby Boomers did at the same stage of life. But rather than join forces, isolated, desperate job seekers undercut each other until all are in slivers. The work platform fiverr.com, for instance, touts outsourcing to freelancers as doing “more with less” and advertises a client ordering a logo design for $30. One of their widely maligned subways ads featured a hollow-cheeked woman with the caption “You eat a coffee for lunch . . . Sleep deprivation is your drug of choice.”

But as the recent sexual harassment scandals have highlighted, in addition to being overworked and underpaid, a growing number of workers are now contractually bound to remaining isolated and powerless. Mandatory arbitration clauses prohibit employees from seeking jury trials when companies break labor laws. These clauses are now often coupled with bans on class action suits, leaving workers no collective recourse if, say, the company stiffs employees or lets a mine collapse on their heads. With such clauses spreading to progressively lower-level employees, such as Target clerks and Hooters waitresses, EPI estimates that more than a quarter of employees in nonunion workplaces are subject to mandatory arbitration—up from 2.1 percent in 1992, and over twice the share of the labor force that is represented by unions.

And it could get worse. The Supreme Court is slated to decide several cases that pit collective action against employee-imposed private arbitration; it may also address “opt-out” clauses, which strip workers of all rights to organize against unfair practices. The conservative majority, with the U.S. Justice Department on its side, is expected to rule in favor of corporations and against workers.

Is there a connection between the erosion of workers’ rights and the persistence of sexual harassment? I asked Karen Nussbaum, who founded the female clerical workers’ organization 9to5 in 1973 and has been organizing and advocating for women and other workers from perches in government and the AFL-CIO ever since.

Women as a sex are trudging uphill. But workers are sliding down, crushed under an avalanche of anti-labor legislation and corporate-friendly court rulings.

“It’s not just unions, but what unions represent as an institution that has your back,” she replied. In the 1970s, when 9to5 asked women where they’d go if they had a problem on the job, “they’d say, ‘I could call 9to5 or NOW or my congressperson.’ After years, we’d ask the same question, and women would say, ‘I could call my mother.’ Around 2000, they started saying ‘I pray to God.’ Now it’s, ‘I just depend on myself.’”

Two contradictory things were happening, Nussbaum explains. Thanks to feminism, women’s confidence and control in their social and family lives were solidifying. But at the same time their “actual power” was shrinking along with the power of the institutions that would speak for them. “Women became personally stronger and effectively weaker,” she says.

In this atmosphere, what should we do? Advice abounds.

“Name it. Shame it. Call it out. Join me, join all of us . . . as we do what’s right for us, for our sisters, for this planet, Mother Earth,” exhorted McGowan at the Women’s Convention.

“Let’s start talking—loudly and urgently—about the sexual harassment problem all around us,” shouts a Millennial columnist in the Chicago Tribune.

Gretchen Carlson advocates fierceness and campaigns against mandatory arbitration.

On CNBC Noreen A. Farrell, executive director of Equal Rights Advocates, encourages men to intervene—to be upstanders, not bystanders.

Forbes counsels employers to institute a sexual harassment policy, including a one-strike-you’re-fired provision. The magazine offers harassment victims eight ways to respond: Keep the evidence, report the offense, get a lawyer, and number eight, “Get the heck out.” (This counsel echoes candidate Donald Trump’s response when asked how he’d feel if someone treated Ivanka as Roger Ailes did women at Fox: “I would like to think she would find another career or find another company if that was the case,” he said.)

Bruenig, in the Washington Post, concludes that we’ve got the laws, we’ve got the consciousness, but some guys are just pigs. We’ll never get rid of sexual harassment.

But each of these solutions is individual—or at best, virtual, through social media. With the exception of one excellent piece by Amanda Marcotte in Salon, no one mentions unions.

Which brings us back to the nineteenth century.

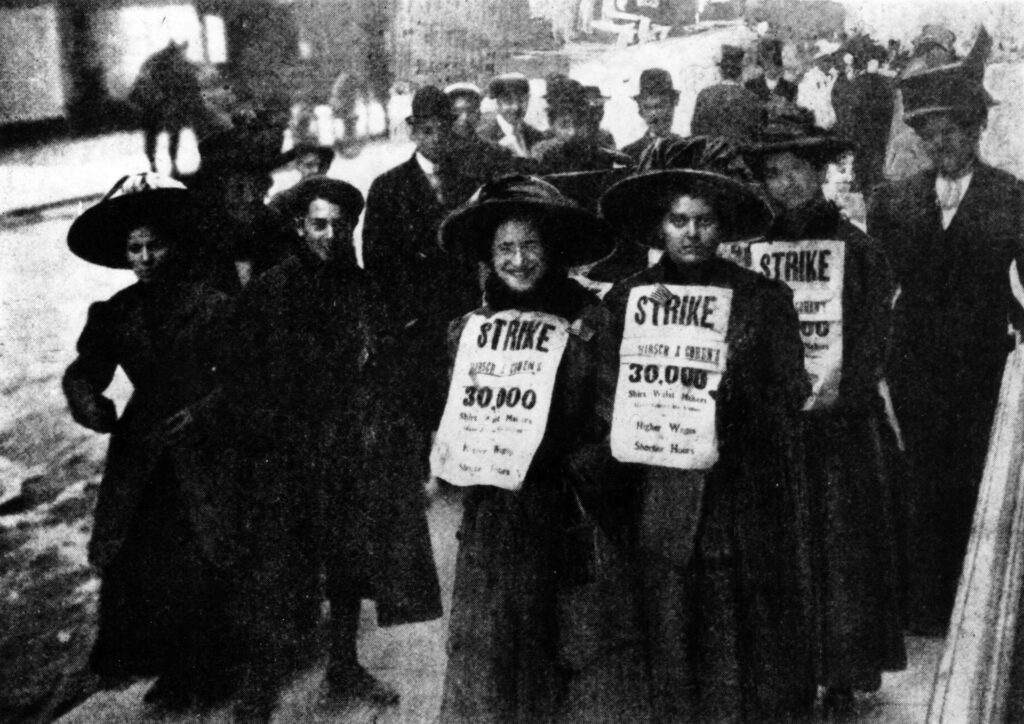

In 1887, in Oldham, near Manchester, England, sixty-eight workers at the Henshaw-street Spinning Company walked out and refused to go back until an investigation was undertaken into the conduct of a head carter named Robert Yates—perpetrator of the storeroom incident described above. Yates did not only persecute women on the job, he took his workplace power, and nastiness, offsite. On one occasion, he dragooned two teenage mill girls into his house, then raped them one at a time while he sent the other out for beer. The girls resisted but refrained from screaming lest they be fired the next day. Having talked with each other at the mill, the molested women went to their union, the Provincial Card and Blowing Room and Ring Frame Operatives’ Association. Both men and women joined the strike. The outcomes were equivocal, according to the British historian Jan Lambertz, writing in the journal History Workshop. Yates was taken to court, fined, and fired. But the women who spoke out and were sacked were not rehired.

In nearby Nelson a few years later, abominations by a tackler, or overseer, at Evans and Berry’s Walverden Weaving Shed mobilized a months-long strike by the Weavers Association, involving as many as five hundred people in demonstrations.

The passage through hell mentioned at the start of this piece was outside Hoyles’ Derdale Mill in Todmorden, England. Unable to stop the harassment by banding together, thirty-one women took their complaints to their union in 1912 and 1913; their testimony stimulated others who had left the mill years earlier to come forward. The grievances inspired W. J. Tout, the male secretary of the Weavers’ and Winders’ Association, to investigate further and enlist the support of press and clergy. It is unclear how successful this campaign was. But Tout’s comment, after dozens of reports, could have been made yesterday: “One thing that has surprised me,” he said, “is the number of people who knew or had heard about these things.”

Elizabeth Hasanovitch, the woman who trembled in her chair, had reason to fear; her supervisor had tried to rape her before. The Russian Jewish New York garment-factory worker was more than afraid, though. She was pissed: “If only I could discredit that man so that he would never dare to insult a working girl again!” she recalls feeling in her memoir.

There’s only one way to end sexual harassment: don’t tweet, organize.

Indeed, as Mary Bularzik recounts in a short history of sexual harassment, at the turn of the century women such as Hasanovitch, under the leadership of passionate, talented organizers, did take men like that on. They rose up against deathly conditions, starvation wages, and the persistent, unwanted, sometimes violent sexual attentions of male superiors. Their activism led to the creation of the Women’s Trade Union League—which organized industrial workers as well as white-collar and domestic workers and those who did piecework at home—and later to the Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. Organizers such as Rose Schneiderman—who famously demanded not just bread but roses too—pressed for reforms women have yet to achieve: equal pay, state-funded child care, and maternity insurance.

Unions have not always stood up for women. In fact many have actively sought to exclude them, along with African-Americans. Union officials have been as guilty of sexual intimidation as handsy line foremen and corner-office satyrs. In Counterpunch the labor activist and writer Steve Early details, from his days working inside unions, their resistance to creating anti-sexist, anti-racist cultures—or action. That resistance has a long history. The British cotton-industry strikes that protested sexual harassment alongside shop-wide grievances about pay or conditions were atypical, notes Lambertz. But they also showed that when class consciousness trumps gender privilege, male workers realize sympathy for their female coworkers with sacrifice and risk.

Those British unionists did not defend or excuse their bosses as boys being boys. “Union solidarity demanded the sacrifice of hypothetical ‘male solidarity’ between officials and a few male overlookers,” writes Lambertz. “For by sending deputations and officials to pressure employers, and by organizing strikes, the unions framed these problems as workplace issues, and implicitly, these women were not just females or sexual beings—they were exploited workers, subjected to unreasonable workplace behavior.”

The outpouring of accusations today reminds us that sexual harassment is pervasive and common. But it is more than men doing bad things to women. Harvey Weinstein and Roger Ailes are not just persons deploying their bodies to keep other persons in their places. As heads of massively rich corporations, they are embodiments of capital, using its power not just against some women, but against all women and all workers.

It is not only unfair to ask women, particularly those in low-status jobs, to speak up or to refuse bad contracts or nondisclosure settlements on their own; it is ineffective. Individuals are sunk without collective support, and women and sexual and gender minorities won’t get security and dignity at work without the solidarity of other workers, including straight, cisgender men.

Yes, women and men both have to speak up against sexual harassment. But there’s only one way to end it: don’t tweet, organize.