“Renoir himself claimed that a film director should have the arrogance to believe that he can change the world but the modesty to believe that if he succeeds in deeply moving four people, it’s a victory,” the great French director Bertrand Tavernier once observed. That wisdom may apply to Tavernier’s own 1992 documentary, La Guerre sans Nom (The War with No Name). Made in collaboration with historian Patrick Rotman, this four-hour film about the Algerian war—the most notable of the handful of documentaries Tavernier shot—did not make much of a splash in France, and it barely managed a few arthouse screenings in the United States before essentially disappearing from circulation. Its viewership stands to expand considerably, however, with its timely release to streaming as part of a larger Tavernier retrospective now available on the Criterion Channel.

Tavernier is best remembered in North America for two dozen disparate, often dazzling, feature films, among them his astonishing debut, The Clockmaker of Saint Paul (1974), the profoundly moving ’Round Midnight (1986), the subtle contemplation A Sunday in the Country (1984), and Dirk Bogarde’s final film (opposite Jane Birkin), Daddy Nostalgia (1990). Tavernier was also an irresistible interview subject, rapturous raconteur, and voracious cinephile, as reflected in his late-career landmark My Journey through French Cinema (2016) and the ten-part television series Journeys through French Cinema (2017–18). With The War with No Name (also known as The Undeclared War), he sought to breathe life into a largely nonexistent national conversation about the blood-soaked military conflict that the French government refused to call a war, in a land that it refused to recognize as a colony. The fighting brought down the fourth French Republic, elicited two attempted military coups, implicated one-time heroes of the resistance in the systematic practice of torture—and in the ruins of its aftermath, in the eyes of most, it was an unpleasant upheaval best forgotten.

Though thirty years old, La Guerre remains a remarkable film—and not only for its evocation of current conflicts, from Gaza to Ukraine. Its 247 minutes, cut down from nearly fifty hours of footage, move briskly and build momentum and even suspense. Withholding virtually all signposts, featuring almost no stock footage, absent expert talking heads, and assuming a good bit of knowledge about the events of the war, the film is comprised almost exclusively of interviews with thirty former conscripts—all of them draftees from Grenoble, the site of one of the largest demonstrations (in 1956) against sending reservists to fight in the war. (Such events, then rare, went unreported in the national media.) The perspectives and politics of the former soldiers are varied, and many are emotionally overwhelmed as they open up about events they had largely been silent about for decades. We often hear Tavernier call “coupez” (cut) from offscreen to allow interviewees to regroup and resume a particular train of thought, or not.

What stands out in a viewing today are not the details of a distant conflict but the universality of the horrors of war: the cycles of utter barbarity and retribution on all sides, the massacre of the innocent, and the enduring consequences.

When the war began in 1954 with a series of attacks against French positions by the Algerian National Liberation Front (Front de libération nationale, or FLN), support for holding on to Algeria—not as a colony, but, in the French imagination at least, as part of France itself—was extraordinarily broad. Thus for eight bloody years, despite the global wave of postwar decolonization, millions of French conscripts found themselves in Algeria, prosecuting a war in which the civilian and military death toll rose to many hundreds of thousands (by some estimates, upwards of one and a half million): overwhelmingly Algerians, though French deaths numbered in the tens of thousands as well. Beyond the exploitative and disfiguring practices of colonial rule itself, the war was conducted with staggering brutality.

As one scholar of the conflict explains, “powerful psychological barriers prevented the French from accepting the Algerian’s claims to independence. From the French perspective Algeria had been part of France for longer than some of its European territories.” Indeed, unlike other overseas possessions accumulated in nineteenth-century imperial adventures, Algeria was legally part of France. It was also home to over one million French citizens (pieds-noirs), many of whom could trace their roots going back several generations and who knew only (French) Algeria as their home. In response to the FLN’s initial attacks, Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France—a socialist generally understood as a passionate anticolonialist—sharply distinguished Algeria from other overseas French possessions such as Morocco and Tunisia. “One does not compromise when it comes to defending the internal peace of the nation, the unity and the integrity of the Republic. The Algerian departments are part of the French Republic. They have been French for a long time, and they are irrevocably French,” he insisted. “Never will France . . . yield on this fundamental principle”—sentiments echoed by other prominent French leftists, including François Mitterrand.

Indeed, with the war going poorly, and in the face of gruesome episodes of FLN massacres against civilian populations, it was a socialist-led government, with the support of the French Communist party, that introduced the 1956 motion giving the military sweeping powers throughout Algeria. It passed 455–76, and draconian measures were imposed. Still, victory proved elusive for the French, and the struggle began to tear at the fabric of French society. In May 1958 a military coup by disaffected generals brought down the government and with it the Fourth Republic, leading to the return to power of Charles de Gaulle and the formation of Fifth Republic—which vested extraordinary powers in the hands of its head of state.

But even De Gaulle would soon learn, as Bob Dylan noted forty years later, that “you can’t win with a losing hand.” The currents of history were not easily swept back. Although government suppression of antiwar sentiment was swift and severe, the brutal, bloody stalemate grew increasingly unpopular. In September 1960, 121 intellectuals and artists—filmmakers François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, and Claude Sautet among them, and Jean-Luc Godard notably not—signed, at great risk to their careers and livelihoods, a manifesto describing the war as an Algerian struggle for independence and denouncing the French army’s use of torture. (The statement was stripped from publications, and its signatories were banned from appearing on national media.) The following year De Gaulle put the matter to a referendum; support for Algerian self-determination won by a landslide, and in 1962 the Evian Accords, establishing a ceasefire and Algeria’s independence, were approved by 90 percent of the electorate. In a bid to undermine the agreement, the right-wing Organisation Armée Secrete (OAS) engaged in terrorist acts and attempted to assassinate De Gaulle—a plot dramatized in Fred Zinnemann’s film The Day of the Jackal (1973).

Judged by Tavernier’s focus on intimate human relationships in his fiction films, La Guerre sans Nom might seem an outlier in the director’s oeuvre. In fact he was a historically inclined and politically sensitive filmmaker. These proclivities, never far from the surface, are most overt in efforts including the spellbinding Life and Nothing But (1989), which takes place in the gloomy aftermath of World War I; Clean Slate (1981), an adaptation of Jim Thompson’s novel Pop. 1280 reimagined in French colonial Africa; and Safe Conduct (2002), an extraordinary and unflinching look, rooted in actual events, at the choices made by filmmakers in occupied France. The Judge and the Assassin (1976) and Captain Conan (1996) also take their place as dramas rooted in historical episodes and steeped in moral ambiguity.

Tavernier’s liberal humanism was forged in his youth. His father—a poet, philosopher, and intellectual impresario—was active as a noncombatant in the anti-Nazi resistance, using his home to host meetings of antifascists and provide sanctuary for fugitive writers. These lessons were not lost on young Bertrand, and his parents encouraged him to pursue a career in politics and law. Jean-Pierre Melville and Claude Sautet intervened on Tavernier’s behalf, making the case to his parents for a life in cinema.

Tavernier was nevertheless often roused to engagement. He coproduced The Question (1977), one of the first films to confront torture during the Algerian war, and the backstory of The Other Side of the Tracks (1997) illustrates the depth and sincerity of his commitments. The documentary came about after Tavernier signed a circular with sixty-five other directors saying they would disobey a proposed law requiring people to inform the authorities if they were aware of undocumented immigrants in their midst. An angry government minister dared the signatories to live for a month in a community with a large population of immigrants to see how they liked it. Tavernier promptly moved to Montreuil, and like it he did: he stayed for six months, and, with his son Nils, chronicled the experience on film. “What could have been a stale lesson in sociology,” Variety wrote, was instead “a rare glimpse of the real people behind headlines about violence, poverty and discontent in the housing projects of France.” Four years later, father and son codirected Stories of Broken Lives (2001), which returned to Tavernier’s cherished hometown of Lyon to document the hunger strike of ten North African immigrants facing deportation. Upon its release, Tavernier embarked on a speaking tour to engage in discussions and debates after screenings of the film. Local officials, he lamented at the time, invariably failed to attend.

It is thus not surprising that Tavernier was drawn to the Algerian war—or rather France’s unwillingness to reckon with it. As he later reflected, the film “was a means of exorcising this silence.” In this, it has clear affinities with Marcel Ophüls’s The Sorrow and the Pity, the 1969 film that lifted a shroud of silence and forced a national reckoning with France’s shameful complicity under Nazi occupation. Jacques Amalric, editor in chief of Le Monde, described La Guerre as the “first film to take a serious look at the scars the war left on the nation” and noted its engagement with “the taboo subject of torture.” Time Out noted similarly that the thirty years after the war were characterized by an odd silence, and the filmmakers were motivated to “break the taboo, to give voice to the repressed past.”

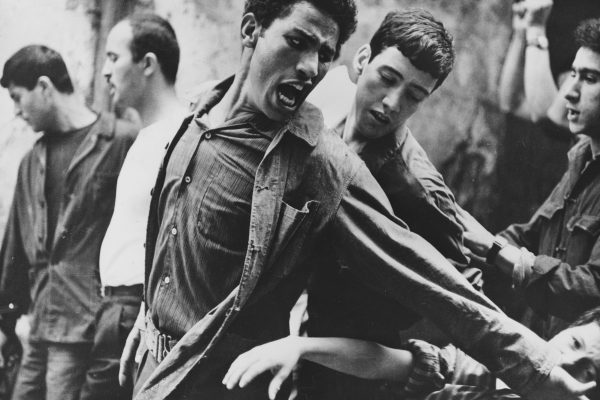

Indeed, the number of notable twentieth-century French films that even flirt with the war can be counted on one hand. There are oblique gestures in Agnes Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) and Jacques Rozier’s Adieu Philippine (1962), which show the melancholia of prominent characters soon to be deployed to Algeria. The most influential film about the war, Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966), was an Italian-Algerian coproduction. Iconic and definitive, it may have set the bar intimidatingly high.

Even the enfants terrible of the Nouvelle Vague largely shied away from the topic over the course of their careers, with just two early exceptions by Godard and Resnais. In 1960, what would have been Godard’s second film (after Breathless), the Geneva-shot Le Petit Soldat, was promptly banned by the French government. Released only after the war, in 1963, the film takes place at the moment of the 1958 military coup that brought De Gaulle back to power. The censorship board, which not only banned the film from screening in domestic markets but ruled it should not be shown anywhere in the world, objected to the film’s suggestion that France’s prosecution of the war “was devoid of any ideal,” to the fact that its protagonist Bruno (Michel Subor) is a French military deserter, and, surely most pointedly, to its depiction of torture. Bruno is held captive and tortured by the FLN with waterboarding and electric shocks; his love interest Véronica (Anna Karina), affiliated with the Algerian cause, is tortured to death, offscreen, by French agents. Released the same year, Resnais’s Muriel features a war veteran who is haunted by memories of a young Algerian woman his regiment tortured to death, events he witnessed (and likely participated in). A menacing supporting player reeks of the still-active and scheming OAS.

In the decades that followed the release of these two classics, however, French cinema, with the exception of a small smattering of obscurities, was conspicuous in its silence about the war.

The War with No Name may surprise viewers familiar with The Battle of Algiers—not due to its lack of battles, but because the action and experiences described take place entirely in the countryside, as opposed to the capital city. The film opens with its motivating query: “Do you often talk about your experience in the war?” Most do not. Tavernier withholds much from the audience; we mostly just see the former soldiers recounting their experiences—at first haltingly, then with greater momentum. The filmmakers turn on the camera and the subjects talk, with almost no editorializing—beyond Tavernier’s sudden burst of voice-over indignation in the film’s final few minutes, when he summarizes some of the challenges veterans of the war had to endure. (Because it was not legally recognized as a war but instead “an operation to maintain law and order” within what was considered France itself, conscripts who fought were eligible for fewer benefits and support than those who fought in other theaters.)

La Guerre’s reluctance to judge its interlocutors will make some viewers squirm; several true believers are given space to express perspectives now very much out of fashion. But the documentary’s minimalist style and posture of observational impartiality belie a cunningly deployed narrative structure and purpose. In interviews Tavernier describes the film as having horizontal and vertical axes. The horizontal is thematic (and loosely temporal), taking on a variety of topics that become increasingly intense; the vertical refers to the layering of the reflections, which become increasingly intimate. The most important implicit debates in La Guerre are not between differently disposed interlocutors but within each of the men themselves, struggling to reconcile their own often contradictory sentiments.

After Tavernier’s opening prompt, the narrative eases in. The director is interested in what it felt like to go off to war at the age of twenty. Many of the now middle-aged men describe feeling an initial sense of adventure at their deployments; those from the provinces had seen little of the rest of France, to say nothing of the wider world. Reality would prove less glamourous. The conscripts recount struggling with their obsolete weapons and the dizzying confusion of their first exposure to hostile fire (usually at night) before settling down into routines characterized by long stretches of boredom (and endless drinking) interrupted by terrifying eruptions of firefights. Increasingly, the FLN looms ominously, as the men recall fallen comrades with the chilling awareness that Algerian fighters, who did not shy away from atrocities against the local population, were especially ruthless with French soldiers. Rarely taking prisoners, the FLN routinely mutilated corpses in ways that could not but invoke terror among those who came upon the bodies.

But as more than one observer recalls, “both sides were equally barbaric.” Here the subject matter turns, increasingly and inevitably, to torture. Almost all the men Tavernier interviews either witnessed it or were acutely aware of what was taking place—some were charged with cleaning up after the fact or returning dazed and battered victims to their cells. All deny that they participated, but a few hint that it was perhaps necessary, hiding behind phrases like “it exists in every war” and “war is atrocious in itself,” with its toxic cocktail of “fear, cowardice and sadism.”

Simply bearing witness to torture, the film makes clear, can be a life-altering trauma itself. One conscript speaks of his shock at a fellow communist who was “a father and a husband” participating in torture, raising that perennial question of how seemingly civilized people can so easily descend into barbarism. The shame of so many of these witnesses produce the most indelible passages of the film. “I was powerless to do anything,” another recalls. “What should we have done? Taken our rifles out and shoot?” The thought that occurred to a twenty-year-old draftee haunted many of these men for the rest of their lives. One physician movingly recounts defying direct orders in attempts to save the lives of Algerians under his care.

As the war limps to its conclusion, La Guerre begins to sum up. Tavernier visits a large facility housing veterans with significant mental health challenges. Some on the right remain bitter about what they see as a betrayal, and an abandonment of allies and brothers in arms by the French government, and about lives scarified. Most are fatalistic. As one puts it, “I lost my certainties. I realized that right and wrong are things better left for young people to dream about.”

Boston Review is nonprofit and relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate here.