The phrase “inner city” is typically used as a convenient way to talk about racial ghettos without having to use words such as “poor” and “black.” It is a geographical euphemism, which relies on a shared image of an ideal American city where race and class are organized in concentric rings around a dense center. We might call this the “donut model” of urban form; it blends class and race and reinforces social separation through physical distance. And it defines middle-class white America as a place—legally autonomous and miles removed—and not just as a demographic category. As a result, failing “inner-city” schools and “inner-city” poverty immediately become someone else’s problems.

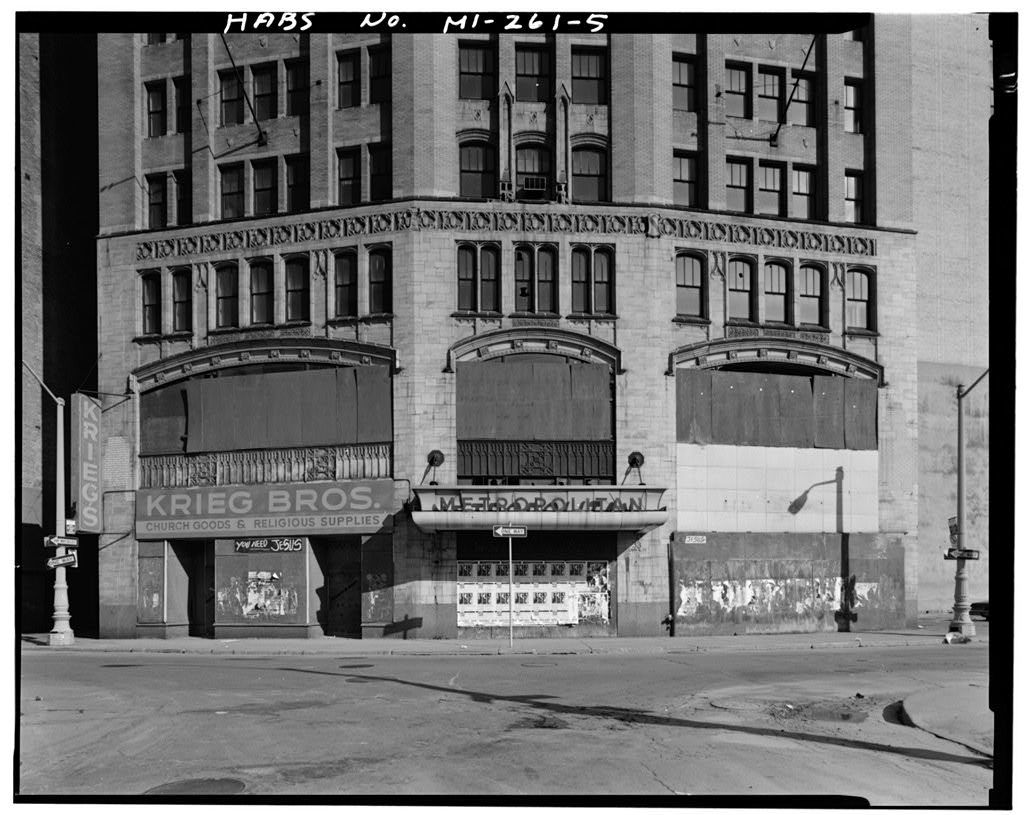

But is this donut model accurate? The maps on these pages show the distribution of race and income in three American cities. A quick glance seems to confirm the basic premise of the inner city: American cities are dramatically segregated by race and by class, and, in general, non-white areas are centrally located and drastically poor. The donut model works especially well for Detroit, where the city limits almost perfectly divide white and black, and successive rings of middleclass and rich suburbs surround a destitute urban core.

But as we look more closely at these maps, the donut model appears increasingly inadequate. First, racial segregation tends not to be ring-like; instead, the two major patterns are wedges and splotches. Houston is a good example of a wedge, and New York is splotchy. (It should be noted that the tendency toward wedges doesn’t depend on the age or car-centrism of a city; what matters is whether its transportation is organized in a hub-and-spoke pattern. Most American cities are wedge-like.) Second, there are abundant exceptions to the ideal of a poor, minority center and richer, white suburbs: every city here has rich enclaves within its borders—not just in “revitalized” downtown areas—and several poor suburbs. And race and class are never perfectly aligned: in every city there are middle-class black neighborhoods, poor white ghettos, and relatively unstudied areas of genuine diversity, which tend to be labeled—misleadingly “transitional.”

Detroit is thus the exception rather than the rule. But it is cities such as Detroit that have been most researched by academics and have therefore most informed our mental maps. Especially important is the legacy of the Chicago School of urban sociology, which first described generic systems of rings and wedges in the 1920s. Its methods have remained influential several scholarly generations later, and today most academic work on segregation still focuses on donut-like cities in the Rust Belt. Even the rise of the Los Angeles School of urban geography since the 1980s has done little to challenge the donut, since these analysts of sprawl and edge cities have had relatively little to say about the traditional problems of racial and economic segregation.

The inner city, in other words, is an idea derived from the study of a small handful of cities as they were several decades ago. By now, not only have demographic trends rendered the binary between rich/white and poor/black much more complex, but municipal boundaries are generally unchanged since the early twentieth century, making the city/suburb divide problematic as well. Racial wedges are expanding beyond city limits, and the ecology of splotches is likewise fully metropolitan.

If not “inner city,” then what? My own inclination is to talk directly about rich and poor, racial isolation, and the municipal tax base. Why not shelve “inner-city schools” and talk instead of underfunded schools with predominantly poor and minority students? And instead of “suburbia,” we would be better served to distinguish upper-class exurbs, middle-class white neighborhoods, and low-density immigrant communities. Avoiding the conflation of race and class means not just creating new social categories, but new mental geographies as well.