Nothing was more exposed than the fallen body of Michael Brown, lain for hours on the hot asphalt of Ferguson, Missouri.

Nothing was more obscure than the circumstances of his death on August 9 at the hands of a police officer.

Now that is changing, with the release of the officer’s name and the publication today of an independent autopsy prepared, at the request of Brown’s family, by the former chief medical examiner of New York City.

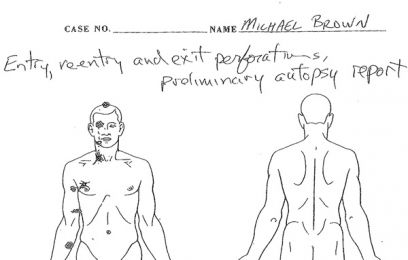

But with this emerging clarity comes continued ambiguity. The autopsy shows that Officer Darren Wilson put at least six bullets into the unarmed Brown, all in the front of his body. This conflicts with eyewitness testimony from Dorian Johnson, an associate of Brown’s who was at the scene and claimed that the officer shot Brown in the back while he fled. And now, courtesy of the Ferguson police, there is a video out that shows the two men stealing cigars from a convenience store a few minutes before Brown was gunned down, a petty crime of which Wilson was not aware. All of this occurs amidst unrest and curfew enforced by police in riot gear a step down from the machines of war that earlier rumbled through the streets of Ferguson to the nation’s overdue horror.

The judicial process cannot account for what matters most: the policies and biases that enable whites to claim justification in the murder of blacks.

What is now underway publicly is the trial of Michael Brown and the trial of majority-black Ferguson. When a police officer or a white person who purports to represent law and order (such as George Zimmerman, who murdered Trayvon Martin, or Johannes Mehserle, who murdered Oscar Grant) kills a black man, the deceased is immediately under investigation. While the official inquiry goes on in secret, the dead man’s character is put under the people’s microscope. The video indulges and deepens the same fear that may have overwhelmed Officer Wilson, who, we should assume, did not set out to kill Brown or anyone else. Yet here is another intimidating black man—six-feet, four-inches tall and 292 pounds—from a hard town. So hard it can only be controlled with humvees, sniper rifles, night-vision goggles, and M-16s. Maybe Michael Brown didn’t deserve to die this way, but maybe, the video hints, we are better off without his kind. We saw the same approach with Martin, who was called a pothead, a fighter, and a troublemaker after Zimmerman ensured the young man was unable to respond to the allegations.

In the Wilson-Brown investigation, the video may play a small part in a drama focused on the defense of justifiable homicide. The law is concerned only with what can be proven in regard to the individual act, so all of the racism being protested and the big guns on city streets won’t matter in court. If Wilson thought he was in physical danger, and if there is even slim evidence to support his claim, he will be in a good position to argue that he was justified in using force. Deadly force is a higher bar, but a shooting is a heat-of-the-moment thing, and, as we are already learning from this autopsy, the eyewitness testimony may be unreliable. If Johnson mounts the stand and says, “Officer Wilson wasn’t in danger, and he shot Brown while he fled with his hands up,” or “Officer Wilson, not Brown, escalated the situation to violence,” the defense will have little trouble responding: “Your eyewitness statement was false, and weren’t you, Dorian Johnson, off with Brown robbing a store ten minutes before the incident?” Johnson’s credibility is shaky; a day in court might bring further shades of the Zimmerman trial, during which Rachel Jeantel, testifying against the killer, was humiliated by defense attorneys.

More information and evidence may yet come forward, changing the complexion of the Ferguson case. But, as of now, it is Officer of the Law and the Peace Darren Wilson versus the corpse of the intimidating, thieving black man of white nightmares.

What the judicial process will not, and cannot, account for is what matters most: the range of policies and biases that enables white men to claim, sometimes successfully, justification in the murder of black men—that allows them to feel they have not just a legal means to escape punishment but a viable chance at impunity. Investigators, soon to be joined by lawyers, are being careful here, and when they are careful, facts start to look hazy—because they are—and when facts look hazy, a space for justification opens. Those facts would look clearer, and the space for justification narrower, if this were another case of two negroes popping each other. Had Brown been murdered by a black civilian, chances are good his killer would now be in custody without bail, waiting for a catastrophically overworked public defender to come to his aid. The outcome almost certainly would be a plea bargain followed by decades in prison.

But Brown was murdered by a white police officer, the Hollywood-ready personification of probity and self-sacrifice for the civic good. So every uncertainty will be magnified; every fault of Brown’s, no matter how irrelevant, will be marshaled against him; and every possible defense will be mustered on his killer’s behalf.

Apart from the needless character assault against Brown, this is as it should be. Wilson, like anyone accused of a crime, is owed due process. If he is charged following a thorough and honest investigation, he should benefit from a strenuous defense, proportional to the gravity of the allegation against him.

But Wilson’s case also should serve as a reminder that due process, on paper a right of all, is in experience a closely husbanded advantage. Not everyone gets the chance to be justified.