Howard Belasco, the owner of Gem Lumber in Soho, was probably mistaken about the day he saw Etan Patz and another boy climbing around the dumpster, pulling out scraps of lumber, behind his store. The boys bought a couple of boxes of nails, grabbed some more scraps, and ran down the street, Belasco told the New York Times. He thought it was 4:30 or 5:00 on Friday afternoon, May 25, 1979.

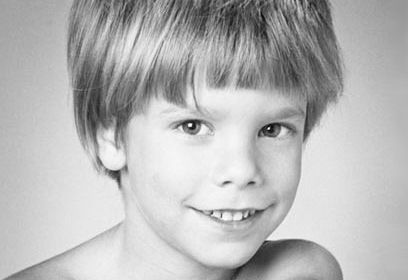

But, of course, if Etan had been alive to hang out with a friend after school, he would have shown up at school. And, as the whole country—and much of the world—would soon know, Etan did not show up at school Friday. That morning the blond, blue-eyed six-year-old left his family’s loft on Prince Street, turned the corner toward the bus stop, and vanished forever.

So maybe Belasco sold the kids the nails on Thursday. Or maybe it was another two kids. If his testimony was useless, there were hundreds more witnesses interviewed by the 500 police officers assigned to Etan’s case. Two months later, when a four-detective team took over, they had over 1,000 reports on file. “We’re following up every lead, every tip,” Detective Thomas J. Finan told a reporter in July.

As late as 2012, when a new suspect emerged, cops excavated the cellar where he said he’d taken the boy. In 2014, the FBI questioned a man in Europe as to whether he was Etan Patz, still alive.

And now, more than three decades later, another suspect, Pedro Hernandez, is on trial. Lawyer Harvey Fishbein says his client—who has an IQ under 70, a history of mental illness, and no corroborating evidence against him—was manipulated into false confession after eight hours of police interrogation. The many accounts of Hernandez’s alleged crime conflict: he stabbed the boy with a knife, or a broom, choked him, sexually assaulted him, did not sexually assault him—or didn’t do it at all. The attorney is trying to instill doubt by deflecting guilt onto another longtime suspect, Jose Ramos, an incarcerated child molester who was a friend of Etan’s babysitter.

No trace of Etan has been unearthed. We will probably never know what happened to him.

But looking back, we can see what happened to us.

“I was [Etan’s] neighbor, and, like every other kid downtown, it could just as easily have been me,” wrote Rebecca Bazell in a New York Times op-ed in April 2012. “Only I didn’t think so at the time.”

Bazell’s piece evokes the most ominous, rarely omitted element of Etan’s narrative: That Friday was the first time his parents let him walk alone to the bus stop, two blocks from home. This, we are meant to believe, was a drastic mistake. As Bazell’s father said to her that week, “There are a lot of crazy people out there.”

The fear that armies of homicidal sex fiends are trawling the streets for young flesh has flared and died out many times in the last 150 years. The early seventies offered a momentary reprieve, when sexual optimism reigned and child sexuality enjoyed a degree of acceptance, even celebration.

But backlash was brewing both among conservatives and feminists who were discovering, and already exaggerating, a scourge of child sexual abuse. By 1977, a paradigmatic pair, LA vice cop Lloyd Martin and feminist psychologist Judianne Densen-Gerber, was traveling the land stoking the claim that 1.2 million children were victimized annually in child prostitution and pornography. Martin told a Christian TV host that pedophiles hang around maternity wards in order to “grab the post-fetuses and sexually victimize them.”

It developed that Densen-Gerber arrived at 1.2 million by quadrupling an unsubstantiated figure a journalist admitted he’d “thrown out” to raise attention. But fear was loosed. Bazell’s stepmother told her “abducted kids were often forced into pornography.”

In 1981, AIDS, mother of all sexual perils, arrived. And the severed head of Adam Walsh, also six, was found floating in a Florida canal. His father, John, joined forces with Etan’s mother, Julie, to publicize an alleged wave of atrocities committed against children. In 1984 Ronald Reagan established the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a quasi-governmental organization, exempt from government oversight, that serves as the United States’s semi-official child exploitation propaganda machine.

For its first campaign, NCMEC induced dairies to print the faces of missing children on their milk cartons. Etan’s was one of the first. The campaign ended because leads were not showing up—and kids were getting the willies while eating their breakfast cereal.

The failure of the milk carton campaigns might have had something to do with a dearth of actual abductions. Today, NCMEC claims 800,000 children go missing annually. But, research shows, about half of those kids are runaways or their parents’ “throwaways.” Another 40-plus percent can’t be located for “benign” reasons—they’re lost, injured, or unaccounted for because of crossed signals between kids and caretakers. About 9 percent are abducted by a parent, usually the non-custodial one in a divorce. And “stereotypical” kidnappings—the Polly Klass, Jessica Lunsford, or Etan Patz scenario? The Bureau of Justice Statistics in 1999 numbered these at just 115, barely a blip in the statistics.

During the exhaustive search for Etan, black children were disappearing in Atlanta.

But in the 1980s, a monster was born every minute, some vastly overblown in number, others altogether invented. Child pornographer, stranger molester, satanic ritual abuser, demonic daycare teacher—each embodied what George Mason University cultural studies professor Roger N. Lancaster called, in Sex Panic and the Punitive State (2011), “the supposed ordinariness of extraordinary abuse.”

Yes, it could have been Rebecca Bazell who disappeared that May morning. But not easily, for her or Etan. There may be a lot of crazy people, but, thankfully, few are crazy in this way.

The monsters haunt us still, and we have built a legal and cultural fortress to hold them off. Nearly 800,000 people are on sex offender registries, thousands in civil commitment, locked up for crimes they might commit. No risk to a child is acceptable, however slim.

Who can remember a time before health club locker room signs asked patrons to report suspicious activity? Before neighbors called the police when they saw kids on a playground or in a parked car without a minder? Before childproof packaging, Baby on Board, and Halloween safety guides alerting parents to the dangers of wigs, candlelit jack-o-lanterns—and, of course, pedophiles proffering candy?

Who can read the Soho lumber store owner’s story without being struck by its nonchalance? Kids playing in a dumpster, even buying nails: unheard of today.

But the difference between then and now is not that the danger has increased. New York’s crime rate is a fraction of what it was in 1979. The difference, as Bazell unwittingly suggested, is that we think it’s more dangerous, especially for children.

May 25, 1979, when that rarest of horrific rare crimes occurred, may be the last day a child could roam in search of adventure, free of adult supervision, neighborly disapproval, and potential legal consequences.

Or rather, a white, middle-class child.

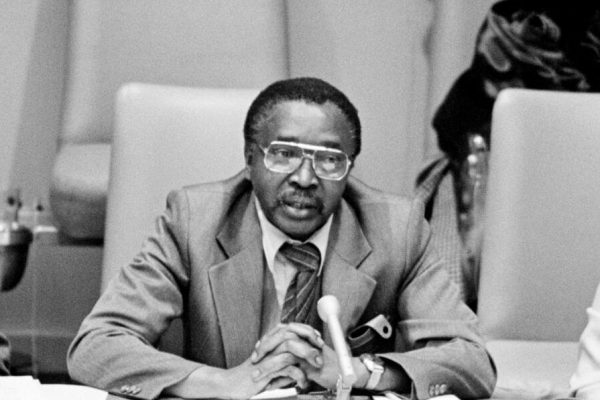

The summer Detective Finan, and helicopters, bloodhounds, and psychics, were scouring Soho for clues to Etan’s fate, African-American children were disappearing in Atlanta. Within four days, two fourteen-year-olds were gone, their bodies found in the woods a few days later. By spring of 1980, twenty-three children had been kidnapped and killed. The youngest, Latonya Wilson, was seven.

Unlike the Soho disappearance, however, which was reported in the New York Times within two days, the national press took no notice of the Atlanta child murders until October of 1980. By then, fifteen children were dead.

And unlike the New York cops, who examined and reexamined every tiny bit of evidence, as reporters from ABC’s 20/20 discovered, Atlanta police were not following up every lead that came in over their hotline, or even writing them all down.

To the media, apparently, black lives did not matter, even the lives of elementary-school children being taken in a slow-motion massacre. To the communities from which the children were disappearing, it seemed that the largely African-American elite running Atlanta were not that concerned about the poor.

As Lancaster’s book shows, the sex panics of the 1980s transplanted white fear of crime from the “inner [read: black] city” to the white suburbs (and neighborhoods like Soho). The ogre shape-shifted too: The “predator,” a putatively remorseless black gangbanger, morphed into the “pedophile” with a white face and a sexual pathology. Accused Satanists and daycare molesters were almost all white, as were their alleged victims.

But as extraordinary crime turned ordinary in the white imagination, and formerly safe middle-class children were suddenly in need of vigilant protection, the ordinary correlates of crime—poverty and disenfranchisement—could be ignored, or condemned as personal moral dereliction and “addressed” by obliterating the social supports that were increasingly blamed as incentives to unemployment.

Today, the dangers of real crime to some real children still seem to strike the news media as dog-bites-man stories. In what David A. Love, at Grio.com, called an “under-the-radar epidemic,” in poor neighborhoods black children are perishing in the crossfire of gun violence. During Labor Day weekend 2013, two one-year-olds were fatally shot—Londyn Samuels, in her babysitter’s arms, coming home from a New Orleans park; and Antiq Hennis, sitting in his stroller in Brooklyn during an attempt on his father’s life.

From 2011 to 2013, twenty-one teens and children, including five under the age of 8, were hit by stray bullets in Oakland, California. One was asleep in bed, another following his dad to take the trash out. Few arrests were made.

According to analyses of national statistics, nearly half of gun deaths and injuries among minors afflict black children and teens, who make up 15 percent of Americans under eighteen. In 2011, black kids ages five to nine—Etan’s age when last seen—were twice as likely to be killed by guns as their white cohorts.

As for violence of a more intimate kind, poverty and its troubles—addictions, overcrowded households, parental stress—are among the strongest predictors of child maltreatment. A study recently published in Pediatrics found that child abuse also increases with income inequality.

STILL MISSING: The phrase evokes the image of a silken-haired boy on the poster that may be the twentieth century’s most effective piece of child-abuse hysteria propaganda. Panic begat overprotection, and today children are unnecessarily missing childhoods of independence, discovery, and self-confidence.

But there is also such a thing as under-protection, an even more pernicious thief of childhood. We need another, perhaps darker, face on the poster. Too many children are still missing.