When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities

Chen Chen

BOA Editions, $16 (paper)

When a friend tells Chen Chen, “All you write about is being gay or Chinese,” he experiences two waves of l’esprit de l’escalier. First he wishes “I had thought to say to him, All you write about is being white // or an asshole.” That stanza break’s tiny delay, and the triumphantly bathetic insult then landed on, suggest not only that Chen is an architect of the inherently funny sentence, but that he can be self-deprecating and defiant in one breath. Chen’s second belated retort—“No, I already write about everything”—is apt: his own work might take as an emblem the image with which he describes his boyfriend Jeffrey, a person who “makes room” not only for the loftily “unseen, unsayable,” but for “half-off Mondays at the conveyor belt sushi place.” This rangy book makes room for the sensual, the prosaic, and the quietly weird (“the head / librarian has turned on the fasten seatbelt sign”), but talkiness is not its most salient quality. These pages admit the palpable silence of white space, and an “unsweet, / uncharming, completely / uninteresting sadness.” Many bring out the sharp ache of parental rejection, an injury so fresh as to seem not yet wholly registered. But the poems that foreground pain also document the heady, fleetingly quotidian. Chen notices the ordinary even in his dreams: an old, Whitmanesque bearded man holding an ice-cream cone and wearing a “look, not of joy but impatience, like him & ice cream / got a meeting, got other hims & ice creams to see.”

—Calista McRae

• • •

The Wug Test

Jennifer Kronovet

Ecco, $15.99 (paper)

The Wug Test opens with a scientific challenge that is also an existential crisis. The first poem presents a theory—“There is a window of time to make language how the mind works”—that becomes poetic food for thought—“Words as milk so the mind survives on language”—that in turn initiates a test: “Prove it.” The volume develops that proof through the lens of linguistics, following the speaker’s relationship to a boy who acquires language late, having grown up without human contact. Deconstructing language to help the boy acquire it causes the speaker to lose it: the poems move toward “aphasia,” “a sky of words you don’t know how to say.” We hear Plath in Kronovet’s “I, I, I,” which becomes “I want / to see-talk, to un-I until it’s all,” and Stein in the question, “What do we encode into words with our bodies as we speak?” and its answer, “It’s right there in red red red,” echoes that position these poems in the tense spaces between words and bodies. Asking how we become ourselves within the unconscious structures of language, Kronovet links language, body, and intellect. She takes a “Trip to Saussureland” in an imperative attempt to “see the way words leave us,” but resists the idea that language leaves us “empty”: the sky is what it hides, what we can’t see beyond it. At times academic, the questions she raises are poignant reminders to interrogate the ways we become our words. These poems are prickly in their direct voices—they bite back—but there is nourishment beyond the spines.

—Kirsten Ortega

• • •

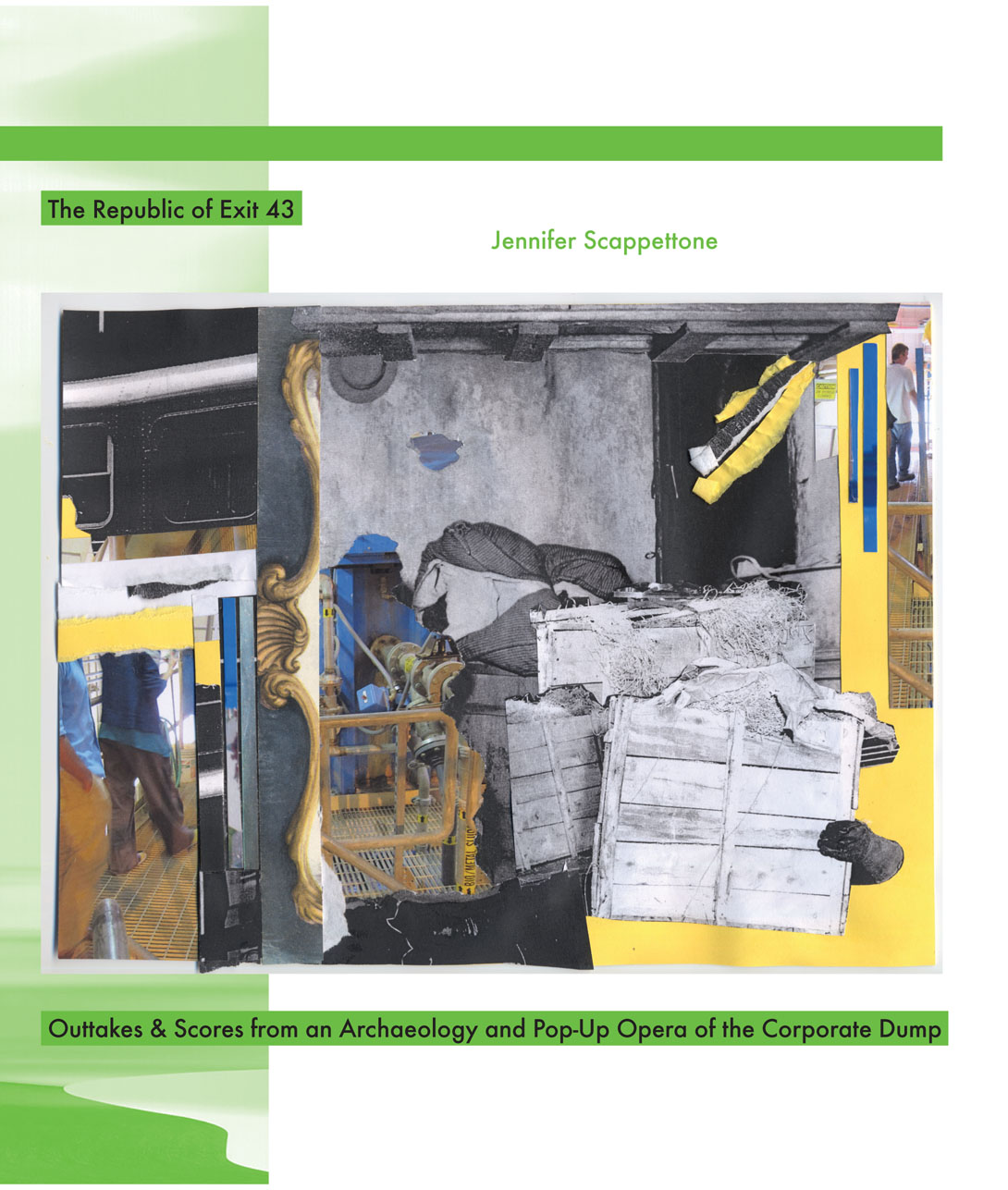

The Republic of Exit 43: Outtakes & Scores from an Archaeology and Pop-Up Opera of the Corporate Dump

Jennifer Scappettone

Atelos, $17.50 (paper)

Jennifer Scappettone's new book is poetry barely containable in book form. The text is a relentlessly inventive and exhausting survey of a landfill visible from space and located across the street from the poet’s childhood home. Lyricism spurred from personal agony alternates with legal jargon from EPA lawsuits and is threaded through with anaphora reminiscent of Alan Ginsberg’s “Howl.” Cornerstones of Western literature such as Virgil and Lewis Carroll are stripped, here, to empty forms and used to sift garbage. Many of the poems appear as full-color collages, mixing image with text. The ambitious “Post-Consumer Confessional Sonnet,” documented and transcribed in the volume, is a literal fence of poetry, which Scappettone built on a loom, each of its fourteen lines reaching out to a maximum of twenty feet. The size and chemical complexity of this poetry, mirroring its subject’s, suggests a post-human audience, perhaps the landfill itself, or some future population able to find meaning in what our present society discards. Each chapter is a shifting sifting strategy: “How we came by fits and starts to salvage garbage by threading the dregs of post-consumer language for a chorus.” In the end the poetry moves beyond the book, pointing us to an augmented reality where we find the poem accessible only by visiting the landfill itself.

—James Yeary

• • •

I Love It Though

Alli Warren

Nightboat, $15.95 (paper)

In Notes on the Cinematograph, director Robert Bresson writes, “One cannot be at the same time all eye and all ear.” Alli Warren’s keenly attentive new collection proves him wrong at every turn. Warren effortlessly blends the analytic mind and the swarming sensorium of the body into a fleshy web of connectivity: “as an ear’s for / tonguing the open out / an ear’s for breathing / engine of thought.” These poems invite the reader into an uncanny immersion within the quotidian—akin to tasting the sharpness of sky color or watching song penetrate office walls. Taken together, their power rests not in the visionary aim of Rimbaud’s “derangement of the senses,” but in the willful blurring of the material limits of language—a rich verbal synesthesia that suggests a collective politics of bodies: muscle, blood and bone. “If I give skin syntax,” Warren writes, “or touch a swallow as it lifts / that a finger might slip.” There is an immediacy here that rides atop this collection’s deftness and depth, its slippery gallows humor (“There is no spring break for debt”) and pathos at deadening routine. This immediacy suggests an urgent present moment that requires holistic attending. Warren’s lean discursive lines wander restlessly, fully awake, curving each poem away from any foregone conclusion: “Tide, bring some / little green thing to dust / behind my eyes.” And if, as Bresson suggests, multiple senses cannot equally rule within the individual, then these poems urge us to merge—friends, lovers, the world itself—into one common body, which, by continuing to feel, multiply resists death: “Share a lung / Accumulate none / Say hello to the crow.”

—Jamie Townsend

• • •

A Turkish Dictionary

Andrew Wessels

1913 Press, $17 (paper)

Finding “the language within the geometric design” and “the language in the art,” A Turkish Dictionary makes meanings via elisions and partialities. Toggling between prose poetry and a minimalist version of a mode akin to Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style (1947), Wessels iterates the same scenarios in different configurations. Wessels’s speaker, propelled by a riveting plot, tries to track down an original of Kemal Atatürk’s inaugural speech founding the modern Turkish nation, to trace the footsteps of the queer poet Ece Ayhan (who, Rimbaud-like, flâneured through Istanbul’s streets), and to teach himself how to see. Punctuating this narrative, spare meditations stage the loss of words Wessels describes, bearing witness to the erasures that shaped Turkey’s monumental public face. Pivoting around a turnstile of “What part is necessary?” Wessels performs erasures on a poem of Ayhan’s, another by Turkish poet Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, and his own poem about seeing a bird. His lines slosh between referent and signifier, as when the speaker “steps down to the number zero” or, like a language learner, recognizes a word living strangely in another word—“alights / (is it light out?)” Deeply relational, each poem lives in light of what has come before it, what losses and emendations have led there. This poetry exists in the interplay of large-scale pieces, travelogue and encyclopedia tessellated with lyric. Wessels seems to reject the idea that poems should be readable to one’s friends, or excerptable. What is needed instead, he suggests, is a dictionary that compasses Chaucer and Wittgenstein and Twombly on the longings of erasure.

—Irena Yamboliev