One tall, thin figure of a woman stepped out alone, a good distance into the empty square, and when the police came down at her and the horse’s hooves beat over her head, she did not move, but stood with her shoulders slightly bowed, entirely still. The charge was repeated again and again, but she was not to be driven away. A man near me said in horror, suddenly recognizing her, “That’s Lola Ridge!”

—Katherine Anne Porter, “The Never-Ending Wrong”

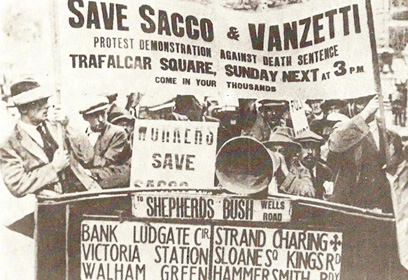

In 1927 the Greenwich Village poet Lola Ridge was known to a huge public as the author of The Ghetto and Other Poems (1918), a book that portrayed the immigrant as human, struggling, but with hopes for the future. Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were two such immigrants, about to be executed in Boston for crimes they most likely did not commit. Ridge too was an immigrant—born in Dublin, she immigrated to New Zealand as a child and later traveled across the Pacific, first to San Francisco and eventually settling in New York. Her presence at the demonstration to free Sacco and Vanzetti—described above by Katherine Anne Porter—was announced in advance on the front page of major newspapers as an important witness to the event. Ridge was also an anarchist when anarchy was a political possibility, especially among intellectuals and artists—and immigrants, those who had left their home country to pursue the dream of freedom in the country that promised it.

Sacco and Vanzetti were also anarchists. That alone made them suspect, and not without cause: they were not the left-wing radicals of Ridge’s circle—poets and painters and critics and philanthropists who picketed with her—but gun-toting subversives looking for trouble. Did they commit the crimes they were convicted for? All their trial revealed was a blatant disregard for civil liberties by the police, and a corrupt judicial system. The presiding judge called Sacco and Vanzetti “Bolsheviki” in public, and announced to the world that he would “get them good and proper.” Even after another criminal confessed to the charges, he would not consent to a re-trial. Leaders all over the world found the situation appalling. Nobel Prize winner Anatole France, who had spoken out during the Dreyfus case in Europe, wrote in his “Appeal to the American People”: “The death of Sacco and Vanzetti will make martyrs of them and cover you with shame. You are a great people. You ought to be a just people.” After the immigrants’ execution, ten thousand mourners attended their funeral, and film footage of the event was considered so powerful that it was destroyed.

Ridge prophesied the multiethnic world of the twenty-first century.

Ridge was an outsider capitalizing on her accent, her sex (female poets were ascendant just then: Babette Deutsch, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elinor Wylie), and her looks. Virginia Woolf–ethereal but without the upper class snobbery, Ridge worked as a model when she first arrived in the United States. Tiny, yet always described as tall, she stood up to the rearing horse, baiting him to turn her into another martyr. “All in the one beating moment, there, awaiting the falling / Cataract of the hooves,” she wrote, describing the confrontation in her last book, Dance of Fire (1935).

Would we remember Ridge now if she had died under that horse? Ridge dead would have emphasized the seriousness of the situation—but the situation was already serious. People all over the world were demonstrating. Sacco and Vanzetti would, most likely, have been executed anyway. The obligation of the artist, and especially the artist-celebrity, is to witness and record—like a journalist, yes—but also to express her feelings about what she sees. Such a highly charged public event had emotional repercussions with huge numbers of people. Perhaps Ridge recognized that by living to write more poems, she might lessen the number of executions—but she did not step back. Did the poems she wrote in the aftermath relieve the submerged guilt, anguish, and frustration of the public? Were the poems, in other words, counterrevolutionary? Poetry—the opiate of the people? Or perhaps it does the opposite, and keeps the issue alive. A few years after the execution, Ridge’s poem “Stone Face” was duplicated by the thousands to remind people of the unjust incarceration of the labor activist Tom Mooney. He went free a few years later.

Ridge was not just a poet of activism. She was one of the first to delineate the life of the poor in Manhattan and, in particular, women’s lives in New York City. The title poem of her second book, Sun-up and Other Poems, is a striking modernist depiction of a child’s interior life. Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry, and William Rose Benét, founder of the Saturday Review of Literature, called Ridge a genius. Four years before T. S. Eliot, an anti-Semite, published The Waste Land (1922), Ridge’s long poem “The Ghetto” celebrated the Jewish Lower East Side and prophesied the multiethnic world of the twenty-first century. “An early, great chronicler of New York life,” Slate summarized when it published Robert Pinsky’s praising column about Ridge in 2011. She embraced her subject along Whitmanesque lines, yet here is a small bomb of a poem from The Ghetto and Other Poems—likened at the time of its publication to the poetry of H. D. and Emily Dickinson—that remains a model of Imagist engagement with the world:

DebrisI love those spiritsThat men stand off and point at,Or shudder and hood up their souls—Those ruined ones,Where Liberty has lodged an hourAnd passed like flame,Bursting asunder the too small house.

Ridge also presided over Thursday afternoon salons filled with modernist hotshots. This was in the early 1920s, while Ridge was the editor of the influential Others: A Magazine of the New Verse and, later, Broom. Eating slices of Ridge’s cake and drinking whatever Prohibition would allow (and not), William Carlos Williams and Robert McAlmon hatched plans for their magazine Contact, twenty-year-old Hart Crane flirted with everyone in sight, Marianne Moore read early drafts of her own work, and Vladimir Mayakovsky stomped on her coffee table.

In 1919 Ridge gave a speech in Chicago entitled “Women and the Creative Will” about how sexually constructed gender roles hinder female development—ten years before Virginia Woolf published “A Room of One’s Own.” “Woman is not and never has been man’s natural inferior,” Ridge announced. Although she wrote little personal poetry, Ridge advocated individual liberty. She supported not only the rights of women, but also laborers, blacks, Jews, immigrants, and homosexuals. She wrote about lynching, execution, race riots, and imprisonment. As a rebellious lefty, she interacted closely with the most radical women of her era, from editing Margaret Sanger’s magazine on birth control in 1918, to reciting her own poems at Emma Goldman’s deportation dinner. Eventually she was arrested during the demonstration against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, and hauled off with Edna St. Vincent Millay. In 1936, watching a parade in Mexico City, she raised her fist in solidarity with the marching Communists.

Despite being declared in her New York Times’ obituary to be one of the leading poets of America, few have heard of her today. She died in 1941 at the nadir of leftist politics, just as the United States was entering World War II. By then Eliot and Pound had very effectively equated “difficult” (read “elitist”) with “good” in poetry. Surely the sixties generation that rediscovered feminism and anarchy would have resurrected her. Not quite. Although her work appears in two important anthologies of the period, and her life as an anarchist should have had great appeal to the revolutionary spirit of the time, her poetry has not been revived. For the last forty years, her executor has promised a biography and a collected works while obstructing access to Ridge’s papers, contributing to Ridge’s relative obscurity and neglect. Feminist critic Louise Bernikow singled out Lola Ridge and Genevieve Taggard as twice-neglected because they were women and radicals, part of “the buried history within the buried history.” Although poetry has always addressed society’s problems and recorded its cultural and political history—whatever its formal precepts—society has not always wanted to hear about them. What has been lost by these omissions is the radical and political tradition in twentieth-century American poetry, and the idea that such subjects were even appropriate for poetry. An entire generation and tradition of American poetry has essentially been amputated from literary consciousness.

Today the same neofascism that Ridge fought in the earliest years of the century appeals yet again to Americans and Europeans in search of order and conformity. An increasing disparity between rich and poor, revived racist agendas, a redefinition of torture, seemingly ineradicable war, violence toward immigrants, and, most disturbing, a discounting of art and culture are now seen as a necessary part of society. The truncated branch of poetry that Ridge represents should remind readers that the discourse of today does not have to take the form that it does, and that many self-evident truths are actually hysterical responses to change or threats to privilege. Poets should have a continuing presence in dissent from those “truths.” “I write about something that I feel intensely,” Ridge told an interviewer. “How can you help writing about something you feel intensely?” The freedom she exercised came at a time when the Russians were in revolution—and the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven upended a urinal on a pedestal (a work for which Marcel Duchamp, her erstwhile friend, stole the credit). Politics + art + free expression + women = fire, Ridge’s favorite image. In 2013 former Poet Laureate Robert Hass published her work in Modernist Women Poets: An Anthology, prompting Publishers Weekly to note, “even sophisticates can still make discoveries here, among them Lola Ridge.” Perhaps Ridge’s time has come at last.

Editors’ Note: This piece has been adapted from the author’s Anything That Burns You: Lola Ridge, Radical Poet, out this month from Schaffner Press (cloth, $29.95). Read a selection of Lola Ridge’s poems here.