News for the Rich, White, and Blue: How Place and Power Distort American Journalism

Nikki Usher

Columbia University Press, $30 (paper)

Saving the News: Why the Constitution Calls for Government Action to Preserve Freedom of Speech

Martha Minow

Oxford University Press, $24.95 (cloth)

A friend of mine used to live in West Virginia. A few years ago, sitting at church, another parishioner asked her what she did for a living. The answer—“I’m a journalist”—came as a surprise: Did that mean, the inquirer went on, that my friend was a liberal? Despite living within commuting distance of Washington, D.C., this woman had never met a journalist before—and she is far from alone. According to the Pew Research Center, only about 21 percent of Americans report ever having interacted with a journalist.

This scene is part of a much larger, now familiar story of distrust and decline in news media. Most scholars agree American journalism, especially print journalism, is in crisis—the biggest at least since the early 1970s, when smart reporters saw that bland institutional objectivity could not adequately cover the roiling culture wars of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The reasons for the crisis aren’t just a matter of style or approach, however, nor is the damage that has been done solely the result of social media algorithms and Trumpist attacks on “fake news.” Two big successes by mainstream newspapers in this earlier period—the publication of the Pentagon Papers by the New York Times in 1971 and the Watergate reporting of the Washington Post—obscured the structural precarity of hard-hitting watchdog journalism, and the truly jaw-dropping profits that monopoly local newspapers brought in the 1980s gave publishers little reason to change how they operated.

Today, the recent financial success of the Times and the cushion of Jeff Bezos’s billions at the Post may once again keep these publications from examining themselves too closely, but more and more observers are agreeing that a wholesale rethinking of how news is produced is necessary if rigorous, trustworthy journalism is going to survive—both financially (as an economic institution) and culturally (as a civic one). Two new books make valuable contributions to the ongoing conversation about what must be rethought and reformed.

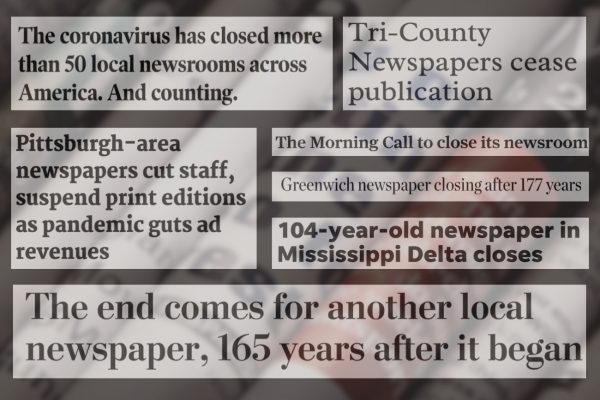

Media scholar Nikki Usher’s News for the Rich, White, and Blue examines the sort of forces at work my friend’s story from West Virginia. Usher analyzes the interplay between journalism, politics, and place, arguing that the loss of local journalism and the rise of concentrated, nationalized news organizations have played a central role in fostering media distrust. As she sees it, the concentration of journalists in a few large, elite, urban, coastal news organizations—typified above all by the Times and the Post—has resulted in news that is mostly aimed at wealthy, mostly white, liberals. As she notes, tens of thousands of journalism jobs have disappeared in the last decade and a half, with newspaper employment dropping an astonishing 47 percent since 2005. She cites an estimate that more than 1,800 U.S. communities have become “news deserts,” places with no local reporting at all. Meanwhile, conservative media outlets have made a concerted effort to delegitimize the mainstream press since at least the 1960s, as Nicole Hemmer has discussed in these pages. Beyond contributing to distrust, a pernicious consequence of news nationalization has been that Americans have lost the habit of local print news consumption. While local television news remains the biggest source of news for most Americans, the “news” these stations report is largely driven by what works well in a visual medium, ignoring stories about city councils and school boards or relying on what’s left of the local newspaper. By and large, the culture of reading print newspapers is no longer thought of as integral to local communities, and the figure of the journalist has become distant, disconnected from you and the way you live your life—not someone you sit next to at church.

Legal scholar Martha Minow’s latest book, Saving the News, has similar concerns: about the decline of local news, the rise of digital echo chambers, the hazards of for-profit journalism, and the implications of all of these developments for democracy. But instead of looking to a growing disconnection from place as the root cause of journalism’s woes, Minow hones in on what she sees as a contemporary misreading of the historically more interventionist approach that government took in supporting a free press. Her central argument is that we must decisively reject popular libertarian conceptions of the First Amendment in favor of positive interventions from the state. To this end, she proposes twelve possible changes to the legal status of news production.

Usher also concludes with five potential “paths forward.” Neither author sees a cure-all, and implementing all of these ideas will surely be a political challenge. But together they provide a compelling vision for securing a future for accurate, independent reporting and restoring the centrality of a trustworthy daily news report to people’s lives.

Central to each of these books is an exercise of historical debunking. Minow’s target is the notion that the government should have nothing to do with journalism—a powerful myth underwritten, Minow explains, by a crudely anti-government interpretation of the First Amendment. The language of the amendment specifies that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech or of the press.” For Minow, the key word is abridging: the Constitution only forbids the writing of laws that abridge the press’s freedoms, not laws that affirmatively enhance the ability of the press to do its job. Indeed, Minow argues, drawing on the work First Amendment theorist Alexander Meiklejohn, federal and state governments have an obligation to support a robust independent press.

For her part, Usher takes on the contention that local newspapers—doing the kind of “journalism that matters” (that is: independent, fair-minded reporting on public affairs)—have been at the core of U.S. democracy from the beginning. As Usher correctly points out, this conception of the press is a relatively recent one, an invention of the age of the post-Watergate large regional newspaper. “The romantic myth of the informed American citizen where every town had its own newspaper is missing an important detail,” Usher writes:

the United States was founded and existed for close to a century without a robust tradition of local news, and most of the news in these plentiful local newspapers was reprinted from other outlets. For much of American history, local news was associated with either salacious scandal or boosterism (or both), and most newspapers were low on original news content.

That’s not the image of journalists that has taken hold in the popular imagination—whether among those who disparage journalists, those who stand by the work that they do, or journalists themselves. The more common conception, as journalists Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel put it in their accessible book The Elements of Journalism (2001), is that “the primary purpose of journalism is to give citizens the information they need to be free and self-governing.” Usher is not totally convinced. “Journalism anchors American democracy by connecting people to the places they live,” she writes, “providing them with critical news and information as well as a sense of cultural rootedness and belonging. As such, journalism enables an active and engaged citizenry.” She acknowledges that journalism often falls short of this ideal but calls it “a powerful and aspirational myth that enables American civic life.” On this view, it isn’t the information gathering that made newspapers important historically so much as the public conversations they facilitated and the sense of place that they gave to their readers.

The history of U.S. journalism bears her out. During the American Revolution newspapers were highly personal, printed more by tradesmen than by what we could call professional publishers. Some, such as Benjamin Franklin, were intensely concerned with public affairs, but many were scurrilous or fanciful, and all more or less straightforwardly reflected the views of their creators. In the early nineteenth century newspapers mostly ran either commercial news—which were quite expensive, the equivalent of leasing a Bloomberg terminal—or were sponsored by political parties, and devoted to promoting their favored candidates. In the 1830s the “penny press” began to appear in large cities, making newspapers accessible to a larger audience, but these were far more interested in circulation, sensation, and entertainment than in edification or political and cultural criticism. The New York Sun of the 1830s famously ran a series of reports on an astronomer who had discovered humanoid bat people living on Mars. The Yellow Journalism period at the end of the nineteenth century brought with it some real reporting, yet the papers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were still full of sensationalism and advocacy. This era also saw the creation of the New York Times and the sale to the Adolph Ochs, whose family has owned it since then. Ochs’s Times pushed hard on what the journalism historian W. Joseph Campbell has described as an information-based model for newspapers. Reform-minded journalists such as Jacob Riis and the early twentieth-century group known as the muckrakers further solidified the idea that good journalism could hold the powerful to account. They were as much social activists as they were detached investigative journalists.

Even as the ideal of journalistic objectivity took hold in the twentieth century—and a professional class of educated news reporters rose out of journalism schools such as the one Pulitzer endowed at Columbia—the ideals of American journalism were established as much in the breach as in the observance. The United States was rife with newspapers in the twentieth century, and the magnitude was paralleled by significant heterogeneity in outlook and approach. “By the 1920s, many more issues of newspapers circulated than the number of households in the United States, and 95 percent of Americans read the papers,” Minow notes. Almost all of them were named for a place: the Boston Globe, the San Francisco Examiner, the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Usher calls these venues “Goldilocks” newspapers: “not big enough to claim national audiences but still big enough to serve a vital role in the larger national news ecology by being the authoritative voice of a city or region, surveilling a geographically specific part of the country.” But even the papers that did sometimes come close to upholding the ideal of accountability for public officials also typically perpetuated the power of those who already had it, particularly when it comes to racial inclusion. (Even today, the staffs of these papers remain predominantly white.) In his recent book The View from Somewhere (2019), Lewis Raven Wallace convincingly argues that objectivity, far from being free of ideology, actually works to perpetuate the ideology of those already in power. This is not to deny, as Juan González and Joseph Torres discuss in their book News for All the People (2012), that there is a long and influential tradition of Black newspapers, in addition to a significant tradition of alternative and countercultural press. But all of that has unfolded against a mainstream primarily produced by and aimed at white people.

Minow reminds us that the government has often played an active role in this history. The creation of a national postal service in 1792 allowed printed material to circulate widely, even to the remotest parts of the new nation. Discounted postal rates for newspapers and magazines made mail subscriptions possible. Taxes on newspapers were struck down by the Supreme Court as being unconstitutional restrictions on speech. Antitrust exemptions supported the rise of the Associated Press and its crafted tone of impartiality. For Minow, the moral is clear: “structural regulation,” she writes, “affects the nature of the news gathered and reported.” Though a confluence of cultural, technological, and business considerations all influenced the development of impartial reporting, Minow is right to note the deleterious effect that federal regulations permitting the consolidation of newspaper ownership have had in allowing those gains to slip away.

Perhaps the largest government intervention in communication industries came with the creation of the Federal Radio Commission—as well as its successor, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—and their claim that the scarcity of broadcast bandwidth gave the federal government the right to license broadcasters and impose a public interest requirement for retaining those licenses. (Minow is personally connected to these developments: her father, Newton Minow, served as the chair of the FCC under John F. Kennedy and has been a noted advocate for public interest broadcasting.) Under the Reagan administration, this Fairness Doctrine was repealed, opening radio and television to the rise of conservative talk radio and also to Fox News. The easing of rules around broadcast consolidation have also helped Fox’s owner, Rupert Murdoch, make himself and his company spectacular profits, without having to worry about serving the public interest.

A slim volume from last year, Ghosting the News, by the excellent Post press critic Margaret Sullivan, covers many of the same themes that Usher tackles when it comes to the loss of local news, but does so through the eyes of a frontlines reporter and critic. For Usher, writing as a scholar, “journalism’s ‘big sort’ matters because place is the essential unit of political power in the United States.”

Usher mounts a compelling argument about the way place shapes journalism today. Newsrooms have consolidated in liberal cities, and for most of them a college education has become a mandatory qualification for a job as a journalist. In addition to the still overwhelmingly white newsroom leadership (with some prominent exceptions, such as Times editor Dean Baquet), regional and class differences unmistakably shape the viewpoints of journalists. The writing in papers like the Post and the Times is targeted to readers who are, broadly, like the journalists themselves. In these conditions, Usher writes, “Quality journalism that powers democracy will be targeted at those who see its value; those with significant cultural capital, if not actual capital; and those who still trust it (now, mostly Democrats). What’s more, quality journalism will necessarily be produced by journalists who have the financial comfort to weather the ups and downs of an increasingly precarious industry.”

Usher roots her explanation of these changes in the idea of place, but it is a slippery concept. Her analysis takes readers through the economic, technological, and cultural changes that have driven geographic and sociocultural concentration of the profession. She devotes one chapter to interviews she conducted with Washington correspondents, who navigate their dual roles as representatives of their home papers and as members of a knowledgeable Washington elite. Another chapter explains the economics of regional newspapers and how they have been decimated by the targeted advertising of Google and Facebook. She convincingly argues that philanthropic support of investigative journalism tends to benefit news organizations in liberal-leaning states—though her research was unable to determine why: whether it’s because blue states have a higher overall confidence in journalism, because news organizations in red states don’t seek funding because they worry that they will be perceived as taking money from liberal coastal elites, or for some other reason entirely. Usher also demonstrates that philanthropic funding doesn’t eliminate the old problem of news organizations publishing news that supports causes dear to advertisers. In fact, journalists who might have done everything they could to publicly distance themselves from advertiser influence will openly work with the philanthropic organizations that fund them, often specifically for causes that are dear to progressives.

In a case study of how place has become disconnected from the production of news, Usher explores the New York Times, which has transitioned from a local to a national to a global enterprise. Though once very much a local paper, the Times grew to have national influence by the early 1960s, and it still maintains a robust network of correspondents in countries other than the United States. When it took over full control of the storied International Herald-Tribune in 2003, the Times first renamed it the International New York Times, and then fully integrated it into the New York Times brand, now publishing as an international edition of the paper. The Times also continues to publish a Chinese-language edition despite being formally banned on the mainland, though it did abandon a Spanish-language edition. Some of the Chinese stories are translations of other Times reporting, but some are intended to reach a Chinese-language audience first.

Beyond coverage, production itself has gone global, too. Times bureaus in Paris and Hong Kong aren’t just there to report on Europe and Asia anymore; they take over the global enterprise while the masthead in New York sleeps. Even some of the production of the hit Times podcast The Daily is done in Paris, Usher notes, so that it can be ready when New Yorkers reach for their first cup of coffee. Rather than competing with other New York papers or even with the Post, the Times increasingly sees itself competing with other global news organizations such as the Guardian—which followed a similar trajectory, beginning life as the Manchester Guardian before rebranding as a national newspaper in the 1960s and then going global. All of this paints a compelling portrait of a new industry increasingly untethered from a particular place.

What is to be done? Communication scholar Victor Pickard recently argued in Democracy without Journalism? (2019) that the way to save the news is to publicly fund it. As Nicholas Lemann noted last year in the New York Review of Books, there has been no shortage of other potential solutions to the problem. While the seventeen calls to action that these two authors put forward are not, in their particulars, all that new, one overarching theme does emerge: policymakers, journalists, scholars, and even news consumers need to detach themselves from mythologies of journalism and romantic ideals of “saving” existing institutions. It is easy for us historians of journalism to see that the era of independent, public-spirited mass media in the United States has been a blip, but for most Americans this conception of the news and the industries that produce it is all that they have ever known. We should try all of the reforms Usher and Minow advance, but the bigger change will lie in rethinking our basic relationship to news, and that will take time.

Usher sees five overlapping roads out of the current crisis. To begin with, she addresses our conception of what journalism should do and how news consumers will access it. We might have to come to terms with the fact that the local print news that we have known for decades has died and move on to a “post-newspaper” consciousness. This leads to Usher’s second proposal: “unbundling” much of what we have come to think of as local journalism—weather reports, entertainment listings, school board meeting minutes—and letting other community institutions take over those functions, leaving journalists free to focus on watchdog reporting. Third, she urges a prioritization of authenticity, diversity, and inclusivity in the news. Fourth, extending her historical myth-busting, she invites us to consider how partisan news can be—indeed has been—a feature rather than a bug of American journalism. Many nations have developed partisan news systems, she notes, and as long as they are fact-based and rely on systems of verification, they have shown that they can support a robust democracy. In fact, most other democracies include partisan news sources as “part and parcel of the reality of journalism.” Usher’s final recommendation is to do more to understand what she calls “news resilience”: the factors that allow communities to continue to work well after the loss of traditional news sources.

Minow’s twelve recommendations for how the government could intervene to save journalism come at the problem from several different angles. They are more specific than Usher’s, but they also stem from her overarching argument that we need to demand positive interventions from the government to support responsible news organizations. She recommends reforms to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act that would allow the government to treat Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other platforms as responsible actors, pushing them to clean up scurrilous news and disinformation. She argues that the government should demand that these platforms pay news producers for the stories they disseminate. In order to regulate these platforms, she argues for classifying them as public utilities, which would allow the government to impose an updated version of the Fairness Doctrine that once regulated broadcasters—perhaps along with an “Awareness Doctrine” that would help social media users be aware of the sources of information that they were consuming and how the platforms’ algorithms chose those sources for each user. She calls for special attention to be paid to bolstering local news and to presenting a variety of news to consumers—not just the news that the algorithms deem the most appealing. And in an echo of Pickard, she also calls for increased public funding for journalism.

Both Minow and Usher understand that no single recommendation will save American journalism, but their call to action is to remind us all—not just scholars and journalists and the already existing consumers of news—that a healthy news ecosystem is important. It is also crucial to get this idea into the heads and policies of those who are in power, and that will surely be an uphill battle in the face of hyper-partisan politics and conspiratorial criticism of an admittedly flawed mainstream press.

Central to this tactical work will be carefully distinguishing between good and bad faith criticism of the news. In the face of Trump-style assaults on the press, it is important to acknowledge that the readers of the Times and the Post are, on the whole, getting excellent print journalism—backed by impressive resources, gathered by smart reporters, and written with a sense of responsibility to the health of the public sphere. On the other hand, as Usher has convincingly demonstrated, even the best journalism has blind spots—in what stories are pursued, in the way they are written about, and in the audiences they are for. There is little coverage of local communities, especially beyond New York City. There is much less diversity in these newsrooms—demographic as well as ideological—than in the population. All this adds up to a legitimate basis for critique. As Usher puts it, “Right now, I worry that if nothing changes, our news media will further facilitate an elite democracy, with journalism that provides information to elites about other powerful elites so they can be held accountable, either through official sanction or the shame of scandal.” This may be important, but it is not enough to sustain a truly inclusive democracy.

Nearly five decades ago, the media scholar James Carey called for the development of a culture of press criticism in the United States. That call still resonates today. As we work to build a robust and responsible ecosystem of news that broadly represents the citizenry, we need to thoroughly analyze and criticize—in good faith—the flawed but essential journalism that we have.