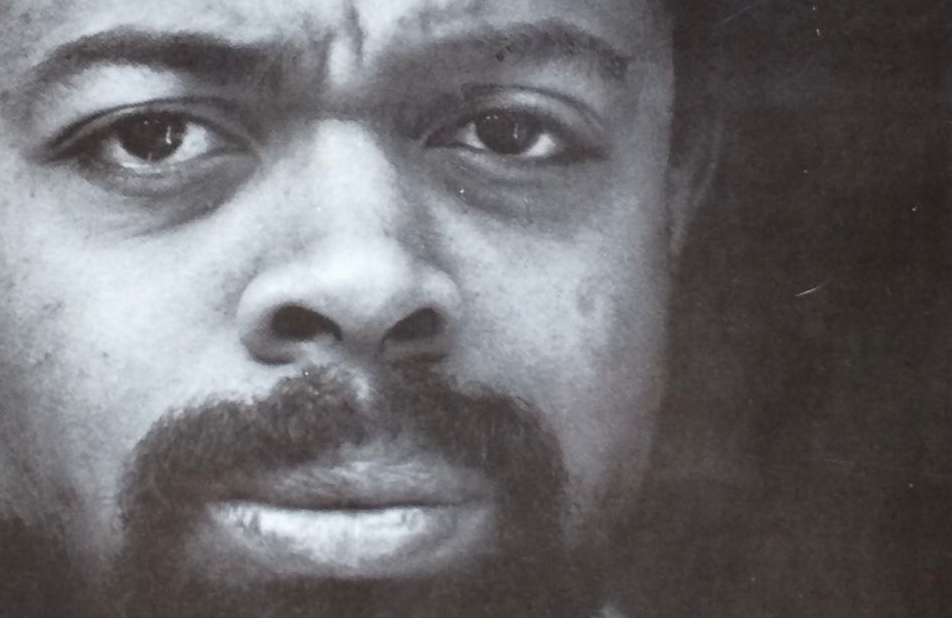

A splinter of language flares into mind before sleep, in crawling traffic or some waiting room of defunct magazines. So a few years ago a phrase began stalking me: A political art, let it be / tenderness . . . words of a poem from The Dead Lecturer by LeRoi Jones (afterward to become Amiri Baraka). I found the book, the poem (“Short Speech to My Friends”), then pored through the pages, as after some long or lesser interval one reads poetry as if for the first time. I’d been taken, unsettled, by these poems in the late 1960s; read some of them with basic writing students at City College of New York and graduate students at Columbia. My Grove Press paperback, with the young poet’s photograph on the cover, has titles and pages scribbled inside the back and front covers, faint pencil lines along margins. A traveled book, like a creased and marked-up map.

I read The Dead Lecturer again partly for the feeling of a time and place, personal and historical: New York in the late 1960s, surges of public expectation and anger, war news, assassination news, political meetings, demonstrations, posters and leaflets; a time lived in the streets, in community centers, lecture halls and student cafeterias, storefronts and walk-ups, coffeehouses and jazz clubs; living room and open-air poetry readings from the East Village to the Upper West Side to Harlem. A time when factions might clash but there was motive and hope in social participation. I read it again realizing, forty years later, how Jones’s poetics had furthered my sense of possibilities when I was writing the poems of The Will to Change and Diving into the Wreck. But I return to The Dead Lecturer here for reasons beyond the personal.

Amiri Baraka’s distinguished, embattled history as poet, small-press editor, essayist, playwright, political activist, autobiographer, and public figure is not what I want to write about here—even if I thought I could do it justice. Paul Vangelisti, in his foreword to Transbluesency: The Selected Poems of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, 1961—1995, and Robert Creeley, in a December 1996/January 1997 Boston Review essay, provide valuable perspectives on a major poetic career. But I would urge any serious student of the human scene, certainly any poet, who has not recently, or ever, read The Dead Lecturer: borrow a copy from the public library, from a friend’s bookshelf, or get hold of it secondhand. (“Used,” “As New,” “Slightly Worn,” say the mail-order book catalogues. The copy in my hands, both used and new, in different senses.) Many of the poems are included in Transbluesency, but The Dead Lecturer itself is out of print.

And it is a book, not an assemblage of occasional poems: a soul-journey borne in conflictual music, faultless phrasing. Music, phrasing of human flesh longing for touch, mind fiercely working to decipher its predicament. Titles of poems are set sometimes in bold, sometimes italics, implying structures within the larger structure. Drawing both on black music and the technical innovations of American Modernism, Jones moves deeper into a new poetics, what the poet June Jordan would name “the intimate face of universal struggle.”

But intimacy is never simple, least of all in poems like these where “inept tenderness” (“A Poem for Neutrals”) searches for an ever-escaping mutuality. Or, in “Footnote to a Pretentious Book”:

Who am I to love

so deeply? As against

a heavy darkness, pressed

against my eyes. Wetting

my face, a constant trembling

rain.A long life, to you. My friend. I

tell that to myself, slowly, sucking

my lip. A silence of motives / empties

the day of meaning.

What is intimate

enough? What is

beautiful?It is slow unto meaning for

any life. If I am an animal, there

is proof of my living. The fawns

and calves

of my age. But it is steel that falls

as a thin mist into my consciousness. As a fine

ugly spray, I have made

some futile ethic

with.“Changed my life?” As the dead man

pacing at the edge of the sea. As

the lips, closed

for so long, at the sight

of motionless

birds.

There is no one to entrust with

meaning. (These sails go by, these small

deadly animals.)

And meaning? These words?

Were there some blue expanse

of world. Some other

flesh, resting

at the roof

of the world

you could say of me,

that I was truly

simpleminded.

No lyric of romantic loneliness and melancholy here. The title suggests an addendum to some literary classic presumed to have changed a life, but the mode is largely interrogative: “It is slow unto meaning for / any life. . . . Who am I to love / so deeply? . . . What is intimate / enough? What is / beautiful? . . . And meaning? These words?” Images bind these questions, render them sensuous: darkness and rain, the sucked lip, the young animals, steel “that falls / as a thin mist . . . . a fine / ugly spray,” the immobility of “the dead man / pacing,” “the lips, closed / for so long,” “motionless / birds.” Together they conjure a landscape of withholding, longing and mistrust. The speaker is not, cannot be, “simpleminded.”

In “An Agony. As Now.” (possibly one of Jones’s most-quoted poems—at least the first few lines) contactlessness and self-barricading are evoked but cannot utter themselves. Nor can “love” decipher them from the outside. But this is not simply one person’s crisis. Robert Creeley rightly saw in it “life . . . in a literal body which the surrounding ‘body’ of the society defines as hateful”—an unacceptable condition. It can be read as common existential anguish, but to ignore that surround of social hatred is to mistake the poem’s diagnostic power:

I am inside someone

who hates me. I look

out from his eyes. Smell

what fouled tunes come in

to his breath. Love his

wretched women.Slits in the metal, for sun. Where

my eyes sit turning, at the cool air

the glance of light, or hard flesh

rubbed against me, a woman, a man,

without shadow, or voice, or meaning.This is the enclosure (flesh,

where innocence is a weapon. An

abstraction. Touch. (Not mine.

Or yours, if you are the soul I had

and abandoned when I was blind and had

my enemies carry me as a dead man

(if he is beautiful, or pitied.It can be pain. (As now, as all his

flesh hurts me.) It can be that. Or

pain. As when she ran from me into

that forest.

Or pain, the mind

silver spiraled whirled against the

sun, higher than even old men thought

God would be. Or pain. And the other.

The

yes. (Inside his books, his fingers. They

are withered yellow flowers and were

never

beautiful.) The yes. You will, lost soul, say

’beauty.’ Beauty, practiced, as the tree.

The

slow river. A white sun in its wet

sentences.Or, the cold men in their gale. Ecstasy.

Flesh

or soul. The yes. (Their robes blown.

Their bowls

empty. They chant at my heels, not at

yours.) Flesh

or soul, as corrupt. Where the answer

moves too quickly.

Where the God is a self, after all.)Cold air blown through narrow blind

eyes. Flesh,

white hot metal. Glows as the day with

its sun.

It is a human love, I live inside. A bony

skeleton

you recognize as words or simple feeling.But it has no feeling. As the metal, is

hot, it is not,

given to love.It burns the thing

inside it. And that thing

screams.

“Self-hatred” is too shallow a diagnosis for this condition.

Here is self-wrestling of a politicized human being, an artist/intellectual, writing among the white majority avant-garde at a moment when African revolutions and black American militance seemed to be converging in the electric field of possible liberations. Experiencing the American color line—that deceptively, murderously, ever-shifting, ever-intransigent construct—as neither “theme” nor abstraction, but as disfiguring all life, and in a time when “revolution” was still a political, not a merchandising term, Jones’s poems both compress and stretch the boundaries of the case. “A Poem for Willie Best” (a well-known black character actor) scathingly quotes the dominant cultural “line” on “the Negro”: “Lazy / Frightened / Thieving / Very potent sexually / Scars / Generally inferior / (but natural / rhythms.” (Such terms may have gone underground but still inhabit popular imaginations, via television and film, African-American political and celebrity figures notwithstanding.) In addition to Best, the poetry’s geography includes Billie Holiday (as “Crow Jane,” after Yeats’s “Crazy Jane” poems), the civil rights leader Robert F. Williams, the poets Edward Dorn (to whom the book is dedicated) and Robert Duncan (cited in two poems), Sartre, Paul Valéry (“as Dictator”), Marx. Lyrically tough as deepest blues, they do not romanticize the black populace as some revolutionary vanguard:

It cannot come

except you make it

from materials

it is not

caught from. (The philosophers

of need, of which

I am lately

one,

will tell you. “The People,”

(and not think themselves

liable

to the same

trembling flesh). I say now, “The People,

as some lesson repeated, now,

the lights are off, to myself,

as a lover, or at the cold wind.Let my poems be a graph

of me. (And they keep

to the line, where flesh

drops off. You will go

blank at the middle. A

dead man.

But

die soon, Love. If

what you have for

yourself, does not

stretch to your body’s

end.

(Where, without

preface,

music trails, or your fingers

slip

from my arm(“Balboa, The Entertainer”)

Out of the verse experiments of William Carlos Williams, Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, and Robert Creeley, Jones had come into association with younger white contemporaries like Edward Dorn, Diane Wakoski, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Diane di Prima, Carol Berg. (All of these and others were published in chapbooks under Jones’s editorship through his imprint, Totem Press, along with his first collection, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note.) In The Dead Lecturer he takes what he needs for breath and measure, committed to the break with anglicized formalism he calls for in “The Myth of a Negro Literature,” his 1962 address to the American Society for African Culture:

No poetry has come out of England of major importance for forty years, yet there are would-be Negro poets who reject the gaudy excellence of 20th century American poetry in favor of disemboweled Academic models of second-rate English poetry . . . . It would be better if such a poet listened to Bessie Smith sing Gimme a Pigfoot, or listened to the tragic verse of a Billie Holiday, than be content to imperfectly imitate the bad poetry of the ruined minds of Europe.

Yet the poems in The Dead Lecturer cannot be called derivative or said to belong to any single school, so imprinted are they with the intensity of Jones’s own personality, intellect, and location. It is the book of an artist contending first of all with himself, his sense of emotional dead ends, the limits of poetic community, the contradictions of his assimilation by that community, his embrace and rejection of it: searching what possible listening, what possible love or solidarity might exist out beyond those contradictions. It is the book of a young artist doing what some few manage or dare to do: question the foundations of the neighborhood in which he or she has come of age and received affirmation. Because Jones himself is implicated, this questioning is double-sided, and sides will be chosen.

“Short Speech to My Friends” moves to the crux of the matter. The voice in the first section of the poem rehearses utopian desire and opposes it against actual disjuncture:

A political art, let it be

tenderness, low strings the fingers

touch, or the width of autumn

climbing wider avenues, among the

virtue

and dignity of knowing what city

you’re in, who to talk to, what clothes

—even what buttons—to wear. I address/ the society

the image, of

common utopia.

/ The perversity

of separation, isolation,

after so many years of trying to enter

their kingdoms,

now they suffer in tears, these others,

saxophones whining

through the wooden doors of their less

than gracious homes.

The poor have become our creators. The

black. The thoroughly

ignorant.Let the combination of morality

and inhumanity

begin.

“Inhumanity”: dehumanization in the eyes of others, entrenched power that inflicts suffering without compunction, and the violence (mostly horizontal) embraced by those who feel no stake in the social compact. A “political art” cannot claim to imagine a “common utopia,” or evoke “tenderness” while enduring this dual inhumanity. But it must somehow bear tenderness for those who “after so many years of trying to enter their kingdoms, / now . . . suffer in tears.” (Or, in “Balboa, the Entertainer”: “But / die soon, Love. If / what you have for / yourself, does not / stretch to your body’s / end.”) The last three lines in this section of “Short Speech to My Friends” flash a signal toward The Wretched of the Earth (1961, translated in 1963), Frantz Fanon’s great study of colonialist violence, pathology, culture, and national consciousness. The poem’s structure spirals like a staircase, where “the society / the image, of / common utopia” turns sharply into “The perversity / of separation, isolation,” this turn signified by a full-stop and capital letter. And, since the poet is located between worlds, there is a necessary ambiguity to the pronouns, the “they” and the “our.”

The poem from which the book’s title is taken, “I Substitute for the Dead Lecturer,” carries Jones’s predicament to the edge:

What is most precious, because

it is lost. What is lost,

because it is most

precious.They have turned, and say that I am

dying. That

I have thrown

my life

away. They

have left me alone, where

there is no one, nothing

save who I am. Not a note

nor a word.Cold air batters

the poor (and their minds

turn open

like sores). What kindness

What wealth

can I offer? Except

what is, for me,

ugliest. What is

for me, shadows, shrieking

phantoms. Except

they have need

of life. Flesh

at least,

should be theirs.The Lord has saved me

to do this. The Lord

has made me strong. I

am as I must have

myself. Against all

thought, all music, all

my soft loves.For all these wan roads

I am pushed to follow, are

my own conceit. A simple muttering

elegance, slipped in my head

pressed on my soul, is my heart’s

worth. And I am frightened

that the flame of my sickness

will burn off my face. And leave

the bones, my stewed black skull,

an empty cage of failure.

What can the practice of the middle-class, avant-garde artist offer to a downpressed and (formally) uneducated people who need poetry, beauty, as much as, or more than, any? To a people who possess elaborate cultural traditions of language and music—of which Jones is well aware, even if they are disdained by his middle-class professors at Howard University—yet from whom, in his present life, he feels ruptured? Fellow artists, unable to feel or hear Jones’s shrieking phantoms, have left him alone with it all: “They have turned, and say that I am dying. That / I have thrown / my life / away.” The voices are internal also: how to give flesh to shadows? This is the beset, conflicted art of one experiencing—allowing himself to experience—a split at the core: Who and what do I work for? What can I offer? What city am I living in? Who am I talking to?

There is no “universal” city but that defined by those who think they rightfully own the cities.

Such questions have engaged many other poets, in cultures outside North America, who believed that art must be a human resource in any genuine seismic shift, that it should belong to those who need it most. But rarely in North America has appeared so morally problematized, artistically self-critical a poetic document. Jones’s fusion of craft and emotional volatility can possess a furious eloquence reminiscent at times of Aimé Césaire.

Allen Ginsberg’s Howl broke expressive limits in 1955, beginning with the wreckage of intelligence (“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness”) through the desperation beneath numbed, Freudianized, complacent postwar America. Howl transposed despair and alienation from individual pathology onto that society itself. In this it is one of our great public poems. But much of Beat-influenced poetry, catching on to the expressive open-form Whitmanic model and the un-Whitmanic machismo, minus Howl’s social insights, easily devolved into self-indulgence, penile narcissism, and tantrum.

In The Dead Lecturer there is neither rant (unless strategically placed) nor self-aggrandizing neurotic angst. There are, however, many sliding screens. “Black Dada Nihilismus” I read as bitter verbal extremism, a send-up of “Dadaist” and nihilist jabber, turned against Eurocentrism. Here it is said of Sartre, “a white man” who had strenuously opposed the French presence in North Africa: “we beg him die / before he is killed.” The injunction to “Rape the white girls” hurls back the deadly lie of white lynching tradition; to “Rape their fathers” an expression of sheer political impotence. Masks and voice-overs are strategic to the poem.

In the poem “The politics of rich painters” Jones mocks the discourse of an art clique he perceives as inhabited by “faggots.” Gay men are made to stand in for the capitalist art world, its class entitlement and hypocrisy. They become the target for rank homophobia, which the poet has failed to disentangle from class (and racial) rage; the language wobbles unsteadily between the two. Minus the homophobic stereotyping this could have been a brilliant satirical poem on the posturing of rich aesthetes:

Whose death

will be Malraux’s? Or the names

Senghor, Price, Baldwin

whispered across the same dramatic

pancakes, to let each eyelash flutter

at the news of their horrible deaths. It is

a cheap game

to patronize the dead, unless their

deaths be accountable

to your own understanding. Which be

nothing nothing

if not bank statements and serene trips

to our ominous countryside . . .The source of their art crumbles into

legitimate history.

The whimpering pigment of a decadent

economy

Published in 1964, The Dead Lecturer is not just a transitional book in a long, controversial career. It is a landmark in itself. After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Jones broke with his former affiliations (including his wife and daughters); moved to Harlem, then Newark; identified for a time as a Black Nationalist, then turned away from Nationalism to international socialism and Third World Marxism; and became Amiri Baraka. In these readings I have wished not to biographize the poems except as Jones gives leave within them; “Let my poems be a graph / of me.” Rather, I am drawn and held by the poet as social being, trying to pierce layers of inhumanity and bad faith, including his own, with language.

For me, perhaps for others, the legacy of LeRoi Jones from this early book is to have made a poetry so personally exposed yet so wide-lensed, asking questions at the crossroads of experimentalism and political upheaval—questions about art, community, poverty, audience, skin, self. His torquing of language is organic to the work; he does not assume that either self-revelation or experiments in language can suffice. The reflexive, un-self-critical use of “jews” and “fags” as familiar, still-poisonous code names for class enemies certainly disfigures the poet’s achievement, along with misogyny and its images craving the woman victim. Jones was writing within conditions that continue to disfigure the American—and human—scene of which he was, and is, though oppositionally, a part. Even the erratics of his art continue to be instructive on that society.

And still there is this painful, visionary music:

What comes, closest, is closest. Moving, there

is a wreck of spirit,

a heap of broken feeling. What

was only love

or in those cold rooms,

opinion. Still, it made

color. And filled me

as no one will. As, even

I cannot fill

myself . . .And which one

is truly to rule here? And

what country is this?(“Duncan spoke of a process”)