In Perth Amboy, New Jersey, members of the Ku Klux Klan assembled to hear a xenophobic celebrity speak. An angry crowd gathered outside the building and as the lecture began inside, protestors interrupted the speaker and tried to shout him down. Eventually the crowd outside forced its way in. Scuffles broke out and several Klansmen were attacked. Later, the Klansmen complained that their constitutional rights had been violated and promised to return in larger numbers, ready to fight it out with their enemies.

It is worth remembering that Americans have a proud tradition of confronting and exposing racist and xenophobic movements.

The confrontation could have taken place during the last year in Berkeley or Portland or any number of cities where racists and anti-racists have clashed. But the Perth Amboy riot was one of numerous confrontations with the Ku Klux Klan that occurred during the early 1920s. The Klan was in a second ascendency, riding a wave of anxiety about crime, immigration, and economic unrest, and like the alt-right today, the Klan sought out confrontations by rallying in unfriendly cities.

In response to white supremacist organizing in our own time, radical voices on the left, notably Antifa, have drawn on the tradition of European resistance to fascists to declare that the appropriate response to racist organizing is physical opposition, doxing (publicly “outing” racists), and violent retaliation. Liberal critics, on the other hand, have argued that Antifa tactics break with U.S. traditions of free speech, open debate, and civility. For the most part, both sides of the debate fail to note that the United States has a long history of homegrown militant resistance to racist organizing. In the 1920s, when the Klan sought to secure a place in the U.S. political mainstream by organizing large public demonstrations and mounting electoral campaigns, anti-Klan organizers confronted the KKK using a range of techniques that included open ridicule and violence. Their goals were similar to anti-racists of today: expose the bigots and deny them the ability to march or rally in public. This all-but-forgotten story serves to remind that as long as racist and xenophobic movements have mobilized in this country, Americans have struggled to confront and expose them using every option at hand.

• • •

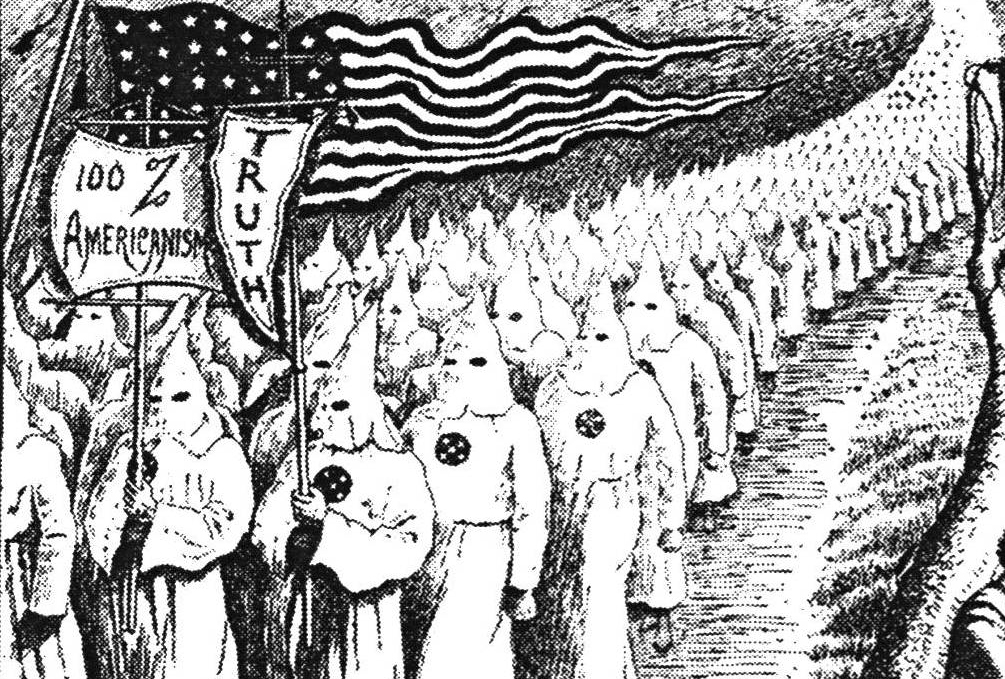

The Klan did return to Perth Amboy three months after the failed lecture, determined to show they would not be intimidated. They rented an Odd Fellows hall downtown and publicized their meeting. Perth Amboy was a multiracial, working-class city but Klan membership was strong in the surrounding countryside and 500 Klansmen, in robes and masks, marched into the building, believing their numbers, and the police, would protect them.

In response, 6,000 protestors surrounded the Odd Fellows building carrying bricks. The police called in the fire department to push them back with water but the crowd slashed the fire hoses with knives and axes. The police fired tear gas bombs, which did nothing to deter the demonstrators, and the Klansmen had to flee out the back door and fight their way through the streets. Most were badly beaten and some had their cars overturned.

What seemed at first like organic anti-racist violence was actually the fruit of organized resistance. In the 1920s, several groups formed to prevent the Klan from gathering publically and to undermine the secrecy behind which they hid. This resistance comprised disparate communities—Catholics, Jews, African Americans, bootleggers, union organizers—unified against the KKK’s vision for the United States. Some organizations, such as the American Unity League, used public shaming and boycotts to counter the Klan’s influence, while a shadowy group known as the Knights of the Flaming Circle confronted the Klan more directly, blocking their marches and attacking their rallies.

By the middle of the 1920s, the KKK was politically mainstream. In some states, as many as a third of white men paid dues.

The original Ku Klux Klan, formed by ex-Confederate soldiers after the Civil War, all but died out by the end of Reconstruction. Then, in 1915, inspired by D. W. Griffith’s film Birth of Nation, a veteran of the Spanish–American War named William J. Simmons recreated the Klan as a fraternal society dedicated to white supremacy. To inaugurate the new organization, Simmons and some friends climbed to the top of Stone Mountain, Georgia, and burned a cross—something they had seen in Griffith’s film but which had not been done by the original KKK.

The Klan grew rapidly, thanks to a range of factors that included rising anti-immigrant sentiment, and the social and economic tumult of the early 1920s. Prohibition, universal suffrage, and rising crime caused many white Protestants to feel that their country was coming apart. The Klan capitalized on these anxieties. Its official newspaper, The Fiery Cross, detailed lurid crimes committed by foreigners and called for restricted immigration. The Klan of the 1920s especially targeted Catholics, playing on lingering suspicions from World War I that Catholics maintained dual loyalties and were part of a secret plot directed from Rome. Klan newspapers derided the “Romans” and “papists” in their midst. The Klan vigorously supported Prohibition and saw its enforcement as a way to terrorize immigrant communities—many Klansmen joined the newly formed Prohibition Unit.

By the middle of the decade, the Klan was on the cusp of integrating into the center of U.S. political life. At its peak in 1925, it boasted between 2 and 5 million members. In some states, such as Indiana, perhaps as many as a third of white men were dues-paying KKK members. The organization successfully ran candidates in local and state elections and even caused a split between pro- and anti-Klan delegates at the 1924 National Democratic Convention. The organization downplayed its racism and emphasized patriotism, Christian values, and what it called “100 percent Americanism.” When its parades and rallies were disrupted, the Klan claimed its constitutional rights were being violated. After one anti-Klan riot, the KKK’s Imperial Wizard released a statement lamenting that “peaceable Americans banding themselves into a patriotic organization are prevented from exercising the same rights as Catholics, Jews and negroes.”

The Klan thrived on secrecy so politicians, public officials, and anti-racist activists aimed to strip away that veil.

This played well in smaller cities and rural counties where most of the residents were native-born, white, and Protestant. But in larger cities across the industrial spine of the Midwest, where Catholics and immigrants made up large majorities, the response was open hostility. The Klan also ran into resistance in the steel and coal regions of Appalachia, where organized labor, especially the United Mine Workers Union, viewed the Klan as a threat to the multiethnic coalition it had built. African American organizations organized boycotts of businesses that supported the Klan and turned Emancipation Day celebrations into anti-Klan rallies. In New York and New Jersey, African Americans organized vigilance committees to defend their communities.

In bigger cities, Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish leaders spoke out against the Klan, as did the American Legion and the Knights of Columbus. Some public officials, especially Irish and Italian politicians, took exception to the Klan organizing in their cities and used their power to persecute its members. They passed laws requiring organizations to make their membership rolls public. They banned parading with masks, and in some places banned the Klan outright, despite the questionable legality of such a move. New York’s mayor, John H. Hylan, dispensed with legal niceties and ordered his police to crush the Klan, to break up its meetings, and seize its membership lists. When Chicago’s fire commissioner discovered that every man at one firehouse had joined the Klan, he had them split up and reassigned separately to Catholic and African American neighborhoods.

In Chicago, a combative Irish Catholic lawyer named Patrick O’Donnell decided to go on the offensive. O’Donnell had been involved in Irish nationalist groups and he used these skills to organize the American Unity League (AUL), which was mainly made up of Catholics but included African American ministers and rabbis in its leadership. O’Donnell reasoned that the Klan thrived on secrecy and, much like anti-racist activists today, aimed to strip away that veil. He paid leakers for Klan membership rolls and sent informers into the organization. In some instances, the AUL broke into Klan offices to get the names. The lists were printed in the AUL newspaper, Tolerance, and in leaflets—a form of proto-doxing. Once exposed, workers lost their jobs and businessmen faced boycotts. In one prominent case, the president of a Chicago bank had to resign from his position.

The AUL also used mockery to diminish the power of the Klan, whose bizarre lingo and silly titles provided easy fodder. Klan meetings were “klonklaves,” a local chapter was called a “klavern,” and the organization’s book of rules was the Kloran. The head of the Klan was called the Imperial Wizard, and local leaders were known as Exalted Cyclops. The AUL dubbed the Klansmen “Kluxers” and “Koo Koos.” It also published internal scandals of klaverns, tales of graft and adultery, as well as testimonies from Klansmen who had quit the organization. The tactics caused great distress among Klan leadership. The Klan’s paper decried the tactics of the “Un-American Unity League” run by “Mad Pat O’Donnell.” The Klan even mounted lawsuits against the AUL for slander and defamation, which ultimately crippled Tolerance financially.

• • •

While the AUL battled the Klan in a publicity war, another, more secretive, organization called the Knights of the Flaming Circle emerged to confront the Klan. Little is known about this organization, but the New York Times reported that around the same time as the second clash in Perth Amboy, the Knights of the Flaming Circle was founded at a huge meeting in Kane, Pennsylvania, at which participants wore robes and set a thirty-foot-high circle on fire. In a letter to the local newspaper, the Knights declared their bitter opposition to the Klan and promised to “ring the earth with justice to all” regardless of race or religion.

Opposition to the 1920s Klan often made for strange bedfellows.

Although the historical record on the Knights of the Flaming Circle is spotty, it seems they were committed to using the Klan’s own methods against them. The press dubbed them the “Red Knights” because they purportedly wore red robes—although, unlike the Klan, they made a point of not wearing masks. They burned circles of hay or tires on Klansmen’s lawns. Like the AUL, the Knights also stole membership rolls and donation records, which they used to publically shame Klansmen, and organize boycotts of Klan-owned businesses. The Knights main function, though, was to disrupt Klan events and organize counterprotests. If the Klan mounted a surprise parade, the Knights would march the next day to voice their opposition. When the Klan announced an event in advance, the Knights would strive to block it in any way they could. In Canfield, Ohio, the Knights of the Flaming Circle scattered roofing tacks on the road to flatten the Klansmen’s tires on the way to a parade.

When the Klan planned a march through Niles, Ohio, in 1924, the Knights of the Flaming Circle called a counterdemonstration of thousands. The mayor had granted a permit to the Klan—despite pleas from local citizens—but refused a permit to the Knights. On the morning of November 1, the Knights of the Flaming Circle set up roadblocks outside Niles, stopping Klansmen’s cars and seizing their regalia. Some of the cars were overturned and the occupants beaten up. The ones who made it through tried to march but scuffles devolved into a riot, which lasted eighteen hours; the Klan parade never took place.

While some of the Knights were motivated by the Klan’s racism and xenophobia, others may have had different reasons. The Klan often attacked local liquor rackets, which in turn were more than willing to defend their businesses and communities with violence, and may well have played a significant role in the Knights. It is also possible that the Knights of the Flaming Circle was never a formal organization at all, but instead a name used to claim victories or rally support by various clandestine anti-Klan activists and bootleggers. In an interview many years later, a member from Youngstown, Ohio, said that the group was a “thrown-together outfit” made up of local ethnic gangs and that the newspapers invented the image of an organization. Jonathan Kinser, who is completing a book on the Knights of the Flaming Circle, speculates that wire services helped spread the group’s legend across the country and inspired others to take up the name: “People would read about the clashes and say, ‘hey, let’s do it too.’”

In places such as southern Illinois, however, the Knights seemed better organized—with meetings and officers—and more prepared to defend themselves against the Klan. In Williamson County, in what is known locally as the Klan War, the Red Knights—with the backing of miners, bootleggers, and the sheriff—battled with Klansmen who enjoyed the support of prohibition agents and local police. The tit-for-tat attacks left several people dead and forced the governor to bring in the National Guard to restore the peace.

• • •

For those who joined the Klan for a sense of belonging, the risks started to outweigh the benefits.

Opposition to the 1920s Klan often made for strange bedfellows. Democrats and Republicans both found themselves battling to keep the Klan out of political life. Immigrant communities that were at each other’s throats, such as the Irish and Italians, joined forces to smash up Klan parades. The Catholic Church found itself on the same side as bootleggers. In short, the Klan had grown so large and antagonized so many communities that anti-Klan activity represented a diverse swath of the country.

The Klan used violence and intimidation to achieve its goals, but seemed overwhelmed when it was opposed by the same tactics, particularly in the North and Midwest. The violent disturbances tarnished the Klan’s reputation as a respectable political organization and in many instances forced the Klan to give up trying to rally and organize in cities that were not dominated by sympathetic residents. According to Kinser, the targeted violence against Klansmen, especially by those with ties to bootlegging, caused a precipitous decline in membership in the Midwest. For those who joined the Klan for a sense of belonging or were motivated by anger over illegal alcohol or immigration, the risks started to outweigh the benefits. By 1926 the Klan had lost all but a symbolic presence in the North, and by the end of the decade, the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan had collapsed under the weight of public scandals, declining membership, and external opposition.

The number of white supremacists organizing today is nowhere near that of the 1920s. But their ranks have increased since the 2016 election, and they are gaining influence in the government and at the margins of electoral politics, riding high on a wave of xenophobia and perceived white victimization. Opposition to them is also growing, but so far only on the hard left. This history reminds us, though, that firm and sometimes violent opposition to racists is a time-honored American tradition, one that has in the past enjoyed support from across the political spectrum, by citizens who may have agreed on little else.