The geologic clock has ticked. The world has slipped from the Holocene—the epoch that officially encompasses the last ten thousand years—into the Anthropocene, the epoch of humanity, in which people are a force, maybe the force, in the development of the planet. Although designation of the Anthropocene remains informal, yet to be adopted by the standard setters at the International Commission on Stratigraphy, the term is now commonly used by scientists, humanists, and popularizers.

The Anthropocene adds nature to the list of things we can no longer regard as natural. Ultimately, as I shall argue, it makes nature a political question. In this respect, the Anthropocene marks the last of three great revolutions of denaturalization: the denaturalization of politics, of economics, and now of nature itself. First came the insight that politics was not an outgrowth of organic hierarchy or divine ordination but instead an artifice—an architecture of power planned only by human beings. Second was the recognition that economic order does not arise from providential design, natural rights to property and contract, or a grammar of cooperation inherent, like language, in the human mind. Instead it, too, is formed by artificial assignments of claims on good and useful things and by artificial means of cooperation—from contracts to credit to corporations. Both politics and the economy remain subject to persistent re-naturalization campaigns, whether from religious fundamentalists in politics or from market fundamentalists in economics. But in both politics and economics, the balance of intellectual forces has shifted to artificiality.

What will the Anthropocene future be? This is necessarily a political question because the Anthropocene future is, unavoidably, a collective human project. The sense in which it is collective is, for the moment, merely empirical: the material life of the species, orchestrated in an increasingly integrated economic and technological order, is shaping the world. Whether this world-shaping project will become collective in the sense of pursuing some shared, though no doubt contested, purpose is a separate question. Only politics can make such projects intentional. To reflect on the Anthropocene today is to confront the absence of political institutions, movements, or even widely shared sentiments of solidarity and shared challenges that operate on the scale of the problems concerning resource use and distribution we now face.

The future of the earth will be the product of the ways in which human beings confront those problems: how we get our food, shelter ourselves, and move from place to place. This is also earth’s past; the first lesson of the Anthropocene is that the present earth is already, in good part, the product of these activities. The question is whether future patterns of human activity will arise from drift and inadvertence or from deliberate, binding choice with a commitment to democratic life.

Partial Politicization and the American Landscape

The Anthropocene is really two ideas. First is the Anthropocene condition: the massive increase in human impacts on everything from the upper atmosphere to the deep sea and the DNA of the world’s species. This condition encompasses a level of species death that many scientists call the globe’s sixth great extinction; increasing toxicity in the water and soil; and the transformation of the planet’s surface by agriculture, cities, and roads. Even wilderness, once the very definition of naturalness, is now a statutory category in U.S. public-lands law. Designated lands are managed intensively to preserve their “wilderness characteristics,” which is not to say they look anything like what might have been in 1491, let alone before human contact. Climate change is the emblematic crisis of the Anthropocene condition, turning the world’s weather into a joint human-natural creation: there is no returning to an undisrupted pattern of weather and climate.

As a practical matter, “nature” no longer exists independent of human activity. From now on, the world we inhabit will be one that we have helped to make, and in ever-intensifying ways. But I do not reject terms such as “the natural world.” To my mind, it is better to keep using them with changed understanding than to promote neologisms. By “the natural world,” I mean simply that part of the world that is not human or, like buildings and cities, starkly and explicitly artificial.

The other aspect of the Anthropocene is the Anthropocene insight. This is the recognition that talk about nature has always been interpretive, not simply descriptive. More specifically, claims about the meaning and value of the natural world have always been, in good part, ways of arguing with and about people. Here, too, but in a different way, nature depends on human activity, in this case the activity of meaning-making.

Arguments on behalf of nature have concealed inequality among people by treating that inequality as part of a given world.

Although they are quite different points, the material and imaginative aspects of the Anthropocene are interwoven. The Anthropocene condition means that, in increasingly important ways, the questions the natural world presents are about how to shape it, not whether or how to preserve it. They are questions involving choices among possible worlds. The Anthropocene insight is not new. It goes back at least to philosophical arguments in the classical Mediterranean, notably the Roman poet Lucretius’s Epicurean arguments against giving moral and theological meaning to natural events. But the insight is harder to escape when people are palpably remaking the world. Moreover, in the Anthropocene condition, the Anthropocene insight has special significance. It entails that the question of how to shape the world is an ethical, aesthetic, and ultimately political one. We cannot turn to a freestanding idea of natural order in order to guide and constrain human judgment.

The Anthropocene insight is evident even in the debate over the Anthropocene itself, in the dizzying range of start dates that scientists have advanced for this new era: they include the advent of agriculture, beginning with rice production in Asia, when atmospheric levels of methane spiked; the European conquest of the Americas, when the planet entered its present stage of global economic and ecological interpenetration; the Industrial Revolution, with its massive increase in carbon emissions; and even the days in 1945 when the atomic bomb introduced a new set of markers to the stratigraphic record, and, not incidentally, conferred upon humans the power to summarily kill almost all life on the planet. With such proposals, it is clear that the question—when did humans qualify as a geological force?—cannot be answered by objective measurement but instead beckons competing ideas about which event irrevocably ended our status as just another species. Which change changed everything? There is no merely factual response.

Among those who embrace the Anthropocene condition, there is also no shortage of proposals as to how “we” might value and shape the world. These ideas range from Pope Francis’s call for stewardship within a political economy of Catholic solidarity to the arguments of Peter Kareiva, the Nature Conservancy’s senior science advisor, who believes that conservation should focus on measurable human benefits, especially those that bolster companies’ bottom lines.

And yet, as these proposals demonstrate, one may recognize the condition while evading the insight. Kareiva and the pope are, of course, making political arguments. But each appeals to the allegedly self-evident lessons of nature, whether it is a divinely created world or, in Kareiva’s telling, a disenchanted and instrumentalized one. To invoke nature’s self-evident meaning for human projects is to engage in a kind of politics that tries, like certain openly religious arguments, to lift itself above politics, to deny its political character while using that denial as a form of persuasion. It is akin in its paradox to partisan mobilization in favor of constitutional originalism, which legitimates solutions to political problems by recourse to extra-political criteria—in the present case, what nature was created to be, or self-evidently is. Such arguments succeed by enabling their advocates to make the impossible claim that only their opponents’ positions are political, while their own reflect a profound comprehension of the world either as it is or was intended to be.

Such partial and selective politicization of nature has played a large role in American politics and law. Arguments on behalf of nature have concealed inequality among people by treating that inequality as part of a given world, part of the order of things. Here, too, the logic of the argument has been that certain things sit beyond the reach of politics because they are natural. Hence ideas of nature have long been invoked to underwrite monarchy and democracy, slavery and abolition, stability and revolution. These models of partial politicization have shaped both social life and the world itself.

The United States was built on an idea of nature as potentially democratic. The natural world, in a theme that sounded across the early republic, cried out to be cleared, planted, settled, and developed. Nature was private property in potential, and it would meet human needs richly if only it were completed with human effort. The land was the substrate of a political economy of settler republicanism and, soon enough, settler democracy, a community of more-or-less equals where labor was not degrading but an honorable mark of doing one’s part in a larger design. In the preceding dominant European ideologies, including the restorationist “natural theology” of England’s seventeenth century, nature had stood for “mutual subserviency,” a chain of obligation tying dependents to lords and kings. Now it stood instead for a kind of equality, whose naturalness was evident in the way the world rewarded the efforts of ordinary people. Nature was even edifying: from constitutional framer James Wilson and President John Quincy Adams to Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole, early Americans argued that the beauty of a well-settled landscape imparted a harmonious character, while the sublimity of waterfalls and mountain peaks inspired noble thoughts and high aspirations. If its settlers only engaged it with energy and attentiveness, the continent would help to form a nation of citizens. Arguing for the preservation of Yosemite Valley as public land, Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Manhattan’s Central Park and father of American landscape architecture, invoked the “duty of the republican government” to provide spaces “for the free use of the whole body of the people.” These would provide a nation of citizens the enriching recreation that Europe’s aristocratic preserves had restricted to elites.

This proto-democratic politics of nature also naturalized a set of exclusions. Native Americans were styled the most natural of peoples—except when their alleged failure to settle and develop the land justified their expropriation and expulsion. Early politicians and jurists varied in whether they endorsed the claim that European farmers had a natural right to expel Native Americans, but the great majority agreed at least with Chief Justice John Marshall, who argued that, with or without natural right, European expropriation was the only alternative to the unacceptable course of leaving the continent “a wilderness.”

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the politics of nature was essential to the Progressive project of building a strong national state justified by its expertise and utilitarian performance. Taking natural resources as the paradigm of their policies, reformers such as Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot argued that the laissez-faire, private-property-oriented development that had settled much of the continent was ill suited to the scale and complexity of nature. Forests, rivers, and soil systems outran the boundaries of private ownership and the knowledge and virtue of the owners, creating crises of over-timbering, erosion, and exhausted fertility. Only government, staffed by experts, could operate at the scale of these resources and with proper knowledge of complex scientific relationships.

Managing timber, waterways, and other natural resources for maximum benefit to the whole political community, present and future, defined the practice that these reformers called “conservation,” which they made the touchstone of their governance. The same managerial utilitarianism, often called “human conservation,” became the standard for public health, antitrust, labor law, and public education, to name just a few areas of policy. These reforms greatly expanded the scope of governance, making much that had been presumptively private—economic relations, childrearing, the use of property—into matters of public concern. At the same time, the reformers’ concept of nature restricted the kinds of judgments that a democratic community might make about these areas of life. In taking natural resources as their model, Roosevelt and his fellow reformers implied that political questions were susceptible to technocratic answers. Roosevelt himself argued that the fraught questions of economic power infusing clashes of labor and capital could take answers from calculations of “national efficiency,” a formula he derived from the principle of conservation. In American politics, the technocratic boundary on democratic argument saw some of its formative uses in this Progressive politics of nature, which was a model of the larger Progressive theory of the administrative state. Like many who today recognize the Anthropocene condition, but not the insight, Progressives either did not see how the division of nature from artifice promoted exclusion, or else they accepted it.

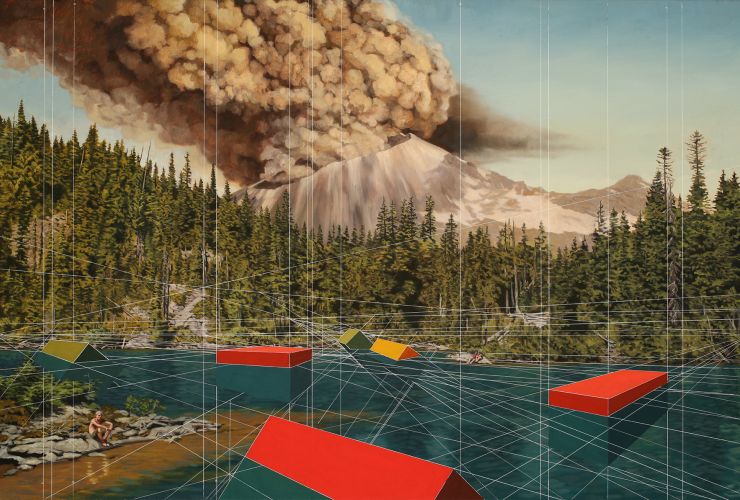

“Crossing,” by Mary Iverson

The same blend of politics and anti-politics marked the Romantic politics of nature, which focused on the aesthetic and spiritual importance of wild and spectacular places. Groups such as the Sierra Club and the Boone and Crockett Club injected these concerns into public-lands politics in the 1890s and afterward. These groups greatly influenced the creation and management of national parks, wildlife refuges, and, eventually, wilderness areas. They built Romantic social movements on the idea that the natural world could elevate and inspire human character. For members of these movements, inspiration and epiphany in wild nature became both a shared activity and a marker of identity. They worked to preserve landscapes where these defining experiences were possible.

This was as generative a politics of nature as any in U.S. history, whether measured in cultural creativity or effect on the country’s laws and landscapes. However, its proponents disguised the political character of their work by claiming that they merely advanced the simple meaning of nature, which they were uniquely qualified to interpret. Sierra Club founder John Muir self-confidently expounded the “lessons” of windstorms, waterfalls, and the high granite vistas where, he wrote, he saw the face of God. His cofounder and longtime ally Joseph LeConte, a geology professor at the University of California, argued for decades that humans completed divine design when they engaged in just the aesthetic appreciation that the Sierra Club prized and cultivated. Thus these Romantics combined a democratic achievement with an anti-democratic, naturalizing twist.

In short, much of the American landscape is the legacy of laws infused with shifting political images of nature, each of which allowed for some kinds of contestation while rejecting others. From national parks and wilderness areas to farmland grids, all were imagined as places where the ideal, intended human relationship to things—and, explicitly or implicitly, to other people—could flourish. The emerging Anthropocene politics of nature may yield a new set of ideals. But if we embrace not just the Anthropocene condition but also the insight—if we accept that there is no boundary between nature and human action and that nature therefore cannot provide a boundary around contestation—we may have the basis of a democratic future. It will be democratic in the double sense of thoroughly politicizing nature’s future and recognizing the imperative of political equality among the people who will together create that future.

Today’s Neoliberal Anthropocene

As ecology, economy, and politics unite with growing intensity—politics shaping the economy, which in turn orders the collective shaping of the world—nature itself will enforce economic and political inequality. Wealth has always meant power to resist natural shocks and carry on living, through medicine, reliable flows of food and water, and security against those who might try to take these for themselves. Thus catastrophe amplifies existing inequality. The global atmosphere is also a great launderer of inequality: everything washes out in the weather, as poor regions see their poverty confirmed by disasters for which no one can quite be blamed, and rich countries demonstrate their resilience, flexibility, and entrepreneurial capacity.

It is too anodyne to say that the planet’s crises create hazards for which wealthy countries are better prepared. More accurately, these countries create a global landscape of inequality in which the wealthy find their advantages multiplied. Human pressure on the world’s supplies of food and water mounts through nominally voluntary contracts. Just as it was once unimaginable that lords would starve when famine struck a feudal society, now it is unimaginable that rich countries will suffer, even in times of global crisis and lack.

In this neoliberal Anthropocene, free contract within a global market launders inequality through voluntariness. It conflates the hard questions of how to use the world’s resources with the general economic questions of how to allocate scarce and valued resources, and it offers answers through the dispersed choices of the market. In its “progressive” form, it incorporates “prices” for “ecological goods and services” and therefore ensures, for instance, that carbon emissions have an economic cost to the emitter and wetlands a value to the owner who preserves them.

But even the progressive managerial model maintains two powerful constraints. First, it accepts vast inequality as its starting point, which it mainly does not question. Second, because its key mechanism is individual choice within the economic frame, it elides the political choice among possible economic architectures. Because each economic order is, in turn, a blueprint for a world that human activity will help to create, this elision of political choice means that the neoliberal Anthropocene is the death of possible worlds.

Tomorrow’s Democratic Anthropocene

The alternative, a democratic Anthropocene, can be forecast only in fragments. To reflect on it is, in part, to reflect on its nonexistence. Indeed, though the need for a democratic Anthropocene is increasingly urgent, it may be impossible to achieve because there is no political agent, community, or even movement on the scale of humanity’s world-making decisions.

We can, however, imagine and work in the direction of what we imagine. Imagining a democratic Anthropocene might begin with a variation on Amartya Sen’s famous observation that no famine has ever taken place in a democracy. That is, scarcity and plenty—comfort and desperation—arise from political choices of distribution, not just natural facts. That process of imagination might begin, too, with the recognition that different worlds, produced by political choice and economic pattern, make possible different ways of life, different uses of and relations with the nonhuman world, different ways of seeing it and seeing one another within it.

One way to make these acts of imagining a democratic Anthropocene more concrete is to look for its potential in vital and generative areas of contemporary environmental politics, where the matter of how and why to shape future worlds reaches beyond the sorts of problems traditionally associated with environmentalism.

The food movement provides a possible model of the next politics of nature, emphasizing the metabolism between humans and world.

One such area is the food movement, members of which take a keen cultural—and sometimes political—interest in how, where, and by whom our food is produced and with what effects. Although it was once easily dismissed as an elite fad, the movement continues to foster unprecedented awareness of how agribusiness shapes landscapes, the global atmosphere, and human and ecological health. It has generated new enthusiasm for participation: for taking a hand in growing, harvesting, or killing one’s food. It has lent salience to the rise of global contractual networks of food provision, such as those between Chinese companies and African governments, critiquing these under the flag of “food sovereignty,” which ties self-government to control of the food system.

The food movement provides a possible model of the next politics of nature. If the old vision of nature was one of wilderness and the pristine, which assumes the separateness of humans and nature, the new one might be agriculture, which emphasizes how the constant, inescapable metabolism between humans and the rest of the world shapes both. Understanding and changing this metabolism has practical stakes, such as limiting fertilizer runoff or averting the emergence of antibiotic-resistant diseases. But it also has cultural and aesthetic stakes: shaping the food economy is a way of shaping the work and play available to people, the kinds of relations they can have to the soil and other living things. As the law of parks and wilderness made possible the iconic experience of the old politics of nature, the Farm Bill, zoning laws, and all the other laws of agricultural create today’s landscape of possible, impossible, and forbidden experiences.

The food movement includes a number of elements that might be generalized to help shape the politics of the Anthropocene. First, it recognizes that the aesthetically and culturally significant aspects of environmental politics are not restricted to romantic nature but are also implicated in economic and policy areas long regarded as purely utilitarian. For example, a beautiful landscape worth preserving so that people can encounter it need not be pristine: it could be an agricultural landscape—preserved under easements or helped along by a network of farmers markets and farm-to-table organizations—whose cultural contribution is that people can work on it.

Second, and closely related, is the movement’s interest not just in the quality of recreation that environmental policy makes possible but also in the kinds and quality of work through which people participate in and alter natural processes. Just as parks policy is cultural policy, so might food policy be. Indeed, it already is, though the nominal goal of supporting independent farmers has mostly been overwhelmed by the political economy of big agribusiness. One can imagine, however, what food policy would look like if set in a recognizably environmentalist register. The most credible food politics would combine an aesthetic attention to landscape with a concern for power and justice in the work of food production. An integrated view of food systems would consider not just the landscapes they create and the picturesque qualities of farm labor but also the safety and welfare of food workers who are often occluded from our sight, whether they labor in slaughterhouses or on industrial-scale farms, such as those of California’s Central Valley. This food policy would seek equal access to nutrition through accessible stores selling affordable produce, provision of adequate school lunches, and food assistance programs for hungry families. In New Deal–era farm supports and other agricultural policies tied to hunger relief, these justice concerns were linked to a utilitarian vision of agriculture as a system that should be engineered for maximum production of calories (within certain economic bounds of demand and efficiency). The new challenge is to put these goals together with an approach to farm-and-food policy that asks what kinds of landscapes agriculture should make and what kinds of human lives should be possible there, so that the food movement’s interest in landscape and work is not restricted to showpiece enclaves for the wealthy.

Next consider the politics of energy. The energy economy was long a largely technical issue for environmental politics, a matter of sulfur dioxide emissions, power plant controls, and carbon-efficiency ratios. None of this is less important now than it was before, but it also belongs in a larger picture, a recognition that each possible energy economy implies a set of landscapes and kinds of human activity, even a version of the global atmosphere’s chemistry and rhythms. Coal shapes the surface of the earth—now more than ever, in the age of mountaintop removal—but also shapes the future of coastlines and weather through climate change. Other energy sources, such as wind power, imply their own versions of disrupted landscapes and their own future atmospheric chemistry.

An Anthropocene revision of the energy economy would involve several critical shifts. The most straightforward, of course, would be to intensify awareness that coal-fired power is tied to mountaintop removal, strip mining, and other damaging practices. The connection between ubiquitous power and faraway destruction must become as vivid and immediate as the fuel efficiency of one’s car. A fuller version of the Anthropocene fuel economy would recognize that, even apart from the most destructive extremes, different energy economies imply different landscapes: mines or windmills, power plants or solar panels, big power lines or distributed grids. Local and state requirements to increase the share of renewable energy sources in utilities’ portfolios are an early stage of this politics. Different energy economies also imply different ways for individuals to engage with the system. In the current energy economy, most people are still cast as mere consumers, whose electricity costs are regulated by a combination of public rate-setting and quasi-market relations among heavily regulated semi-monopolists. Distributed energy systems, such as those incorporating household solar production, treat participants as co-producers of energy. Net metering technology shows the share of a household’s power coming from, or going to, the grid. Other schemes allow users to specify that they want their power bills assigned to renewable energy companies, providing an increased market share for such companies, which would be largely nonviable if their power contributions were not differentiated from those of coal-fired plants. Here, again, issues of justice and power arise: as long as the move to renewably produced power is posed as a private opt-out from the traditional power grid, it presents the risk of a so-called utility death spiral, in which the poorest consumers are stranded on the traditional grid and face mounting rates to fund its fixed costs. A comprehensive recasting of public energy policy could avoid these inequitable results, but there is no ecotopia in any of these futures: the aesthetics of windmills are much contested—they harm migratory birds—and solar panels have big land-use footprints.

From these concrete contests over the future of energy, new alignments and visions can emerge. It is helpful to remember how recently the basic terms of today’s environmental politics came to be and how far they were from being obvious. “The environment” itself was a novel term after World War II and grew in prominence during the 1950s and ’60s, taking definite shape as a category of problem and a special topic of politics. In earlier decades, it would not have occurred to Progressive managers or Sierra Club activists to unite a congeries of challenges—urban sprawl, litter, radioactive fallout, air pollution, national parks management, dwindling biodiversity—under a single label as problems of “the environment.” By the beginning of the 1970s, the category was almost self-evident, and its associated movements inspired a wave of legislation in the United States and much of the developed world. The environment had to be invented before it could be saved. Its invention placed one cluster of issues at the center of the public’s attention while leaving others—such as food and energy, or the inequalities now to be rectified according to the demands of “environmental justice”—on the margins. In recovering some of those neglected issues and making them central, today’s environmental politics may contain the beginning of new syntheses of ideas and action for the Anthropocene.

What Is “Environmental”?

In the Anthropocene world, what does it mean to call some politics “environmental”? If climate change or the energy economy is not environmental, then nothing is. But these issues also touch everything else: technological development, public health, the shape of the economy. If everything is environmental, then the term has no use.

One sense in which it still makes sense is to capture the dimension of each issue that concerns the value of the world and the meaning of the human place in it. What kind of beauty, surprise, and harmony does our half-made world provide? Which half-built landscapes can we see there, and how can we work and play in them? How will our time in them move us, help us to see ourselves differently, and throw out unexpected prompts for the next politics of nature? This question is present in food, energy, and the management of global climate disruption. It is aesthetic and, if you like, spiritual. It is also thoroughly political, although the politics adequate to the challenge does not exist yet, except in fragments.

What is the role of justice in this politics? Environmental justice has been a catchphrase for two decades, but it usually refers to nothing more than the distribution of pollution and other environmental harms. It is important, but not surprising, that this distribution tracks that of other kinds of vulnerability in highly unequal societies. In the Anthropocene, environmental justice might mean not just equal protection against ecological degradation but also an equal role in shaping the future of the planet, contributing vision and priorities to a politics that has often been elite and elitist. It might mean, for instance, that someone from Appalachian highlands being shattered for coal mining or a West African village whose farms are controlled by Chinese overseers would have a say in how her world is remade, a privilege already taken for granted by those lucky few who live near the mountains outside Boulder, in the Berkeley Hills, or in the suburban Boston woods around Walden Pond. It is too easy to say that, in the Anthropocene, we have to get used to change—a bromide that comes most readily to those with some control over the changes they confront—when the real problem is precisely how to build politics that can make the next set of changes more nearly a product of democratic intent than they currently seem destined to be.

Even that thought, however, is a reminder that this is only a fighting chance, part of a fighting future. The politics of the Anthropocene will be either democratic or horrible. That alternative is no guarantee that a democratic Anthropocene would be decorous, pleasant, or admirable, but only that it would be a shared effort to shape our more-than-human future with human hands.