A Tradition

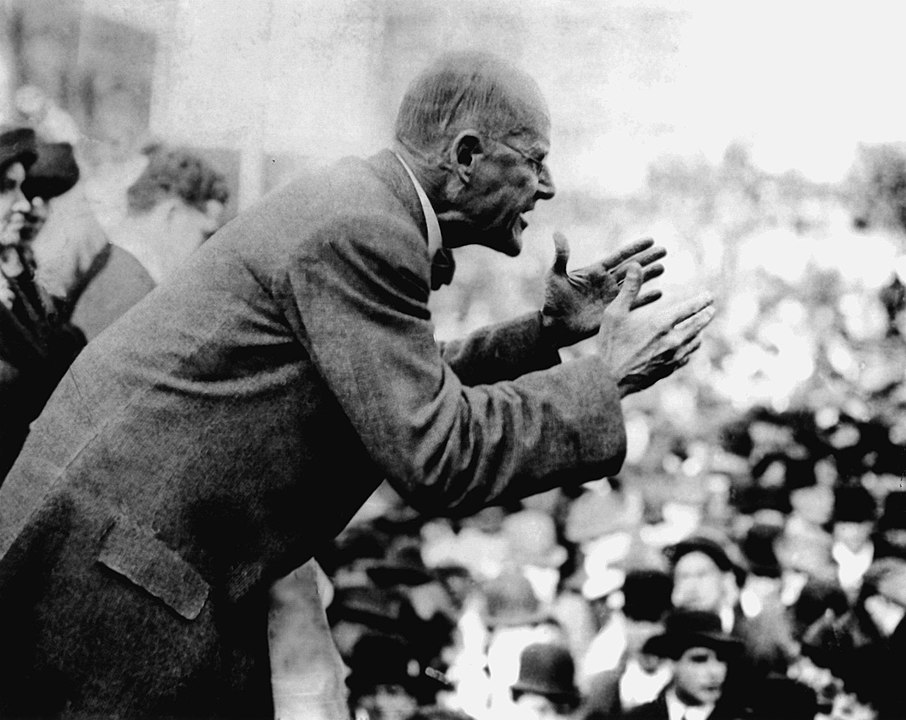

One hundred years ago, Eugene Debs entered Woodstock Prison to serve a six month sentence for having led the great Pullman Strike in defiance of Federal authority. While in prison, Debs decided to transform himself from a union leader to a leader of a general movement for political change. Debs’ Woodstock “conversion” (as he liked to romanticize his jailhouse political reflection) set him on a path which soon led to the formation of the American Socialist Party, and to his crusades for the presidency on the Socialist ticket. Debs’ decision is a way to mark the beginning of the organized left in America.

Debs’ vision of a commonwealth based on justice and equality depended on unifying the struggles of working people and channeling those struggles into the political process: a united working class using the ballot could gain political control and operate the economy for the good of all. Several decades of American leftists were powerfully influenced by that socialist vision, and by the strategic model of a working-class-based party as the vehicle for overcoming capitalism.

But the left tradition, even for Debs, meant more — and less — than that vision and strategy. Left-wing activists have struggled for freedom of expression and political rights within capitalism. They have struggled against racist institutions and for sexual equality. They have articulated visions of personal liberation, egalitarian families, democratic education, sexual freedom, and religious heterodoxy. They have battled the war machine and the media monopolies. They have organized defiance to institutional authority, taken to the streets, boycotted, struck, sat-in — as much as, perhaps more than, they have used the ballot.

So there’s never been a monolithic left, or even a particularly coherent one during this century. Still, there has been continuity of thought and action — a tradition. And one way to summarize that tradition is that it has been about democratization — fulfilling the founding premises of political democracy, extending those premises to the economy, and reinforcing them by enabling all to share the rights of citizenship, as well as their material and cultural prerequisites.

Until the end of the 1960s, moreover, national organizations played a central role in sustaining that tradition. American leftists were, if not unified, at least oriented by national organizations exercising long-term leadership. The current absence of such organization seems, then, to confirm the conventional wisdom that the left no longer exists. But that wisdom is wrong. Millions of politically engaged people identify themselves as “progressives,” “liberals,” “leftists” — even “radicals” or “socialists.” Some are full-time organizers and activists, continuing to work as staff members in unions, community-based organizations, and national and local groups devoted to social equality, civil liberties, the environment, and the rights of the disadvantaged. Many more, though neither organizers nor activists, devote sizable time, energy, and money to sustaining progressive causes. And a still larger number try to express in their lives values and codes flowing from one or more of the currents of the left tradition: feminism, environmentalism, pacifism, socialism, cultural liberation, and legacies of “ethnic” struggles for justice.

For the past 25 years, despite the absence of national organization, the democratic project has continued. In this period, feminism and environmentalism penetrated to the American grassroots and fundamentally reshaped American culture and local politics; American universities began to open up to the intellectual perspectives and cultural legacies grounded in minority and women’s experience, and have been struggling to find ways to integrate specialized knowledge and democratic aspiration; and unprecedentedly large numbers of people joined progressive campaigns — for a nuclear freeze, gay rights, and a Jackson presidency; against US intervention in Nicaragua and El Salvador, and apartheid in South Africa.

By the end of the 80s, however, activists recognized that they were badly fragmented, internally divided, considerably demoralized, without national voice and visibility. The 1992 election seemed to promise a new era for the left — if only because Clinton-Gore promises of a government responsive to the needs of economically and environmentally threatened communities would help mobilize grassroots demand to fulfill the hopes thus created. Instead, demobilization and demoralization have become even more pervasive. We are being overtaken by a sense of despair, as we are forced to defend what we have long thought settled, and find appeals to reason, common sense, compassion, and the Constitution cynically dismissed. At the same time, we see widening economic and social inequity, declining living standards, increasing poverty. And in the face of this, no national political leadership speaks for the interests of those whose livelihood and security have eroded — let alone for those who are already destitute.

There is a growing gap between what needs to be done and what we are doing, and overcoming it will require that we first face up to the reasons for our current demobilization.

Collapse

For the past 100 years, all the great mass movements for social equality have seen the national state as the target, arena, vehicle of their political hopes. In their beginnings, these movements were about democratizing the state — winning vote and voice for masses of excluded people. Beyond such elementary democratic rights, movements have sought to make the state an instrument for overturning civil oppressions and injustices. Social movements — and, in Europe, the social-democratic parties — envisioned the state as the primary vehicle for reducing economic inequity, advancing equality of opportunity, and protecting people from the downside of a profit-driven economy. Finally, in the post-World War II era, movements and left parties supported various models of state-steered economies to reduce the human costs of the business cycle and ultimately to organize the economy for steady growth and optimal community well-being. In Europe, these models were largely hammered out and implemented by national parties with working-class constituencies. In the United States, similar strategies were formulated with far less coherence and coordination within the labor and civil rights movements, and among reformist intellectuals. Broadly speaking, then, the strategies of leftists in the United States and other democracies all embraced the vision of a strong national state, based in popular majorities, oriented toward a more democratic distribution of power and wealth, restraining corporate excesses, using its fiscal power and its authority to promote economic growth and a just distribution of its benefits.

This state-centered perspective was so popular and so evidently rational that, by the 1960s, it was assumed, throughout the West, that a centrist version of the welfare state was The Model for a stable social contract. The common future would be a political democracy, a mixed economy featuring a strong state and big corporations partnered for planning, strong political parties and labor unions representing the unpropertied masses, and a large body of socially concerned intelligentsia publicly funded to do the research, theorizing, planning, and teaching that would foster rational problem-solving.

The American new left arose in large part in resistance to this “corporate-liberal” model. Its founding document — SDS’s Port Huron Statement — argued for resistance to a future determined by elites and dominated by centralized bureaucracies; it called on young intellectuals to find vocation serving disadvantaged communities rather than such bureaucracies. And its vision of “participatory democracy” represented an effort to imagine and organize an alternative to the dominant vision. We thought that corporate liberalism, if it worked, would mean the death of democratic possibility. Moreover, we said, it wasn’t working: poverty, pervasive racism, the destruction of communities and neighborhoods, and the regimentation of mind and spirit all pointed to the failures of social engineering. And corporate-liberalism was, in any case, organized more for warfare than welfare.1

The participatory ideal underscored our differences from the traditional left. The dominant spirit in the 60s was neither social-democratic nor statist/stalinist/leninist, but owed more to anarchist/pacifist/radical democratic traditions: Students and workers should claim voice in the institutions they inhabit; communities and neighborhoods should have democratic control over their futures; coops, communes and collectives should be the places to try alternative futures and practice authentic vocation; civil disobedience and theatrical action were more valid means to make history than running for office. New left organizers worked in relation to established liberalism — but always in strong tension, trying to implement a decentralist strategy in opposition to bureaucratic efforts to temper or channel grassroots demand. So, rather than simply endorse the War on Poverty, SNCC and SDS organizers used its rhetoric of empowerment to mobilize poor communities and challenge the power of entrenched urban machines and federal bureaucrats. Rather than simply supporting liberal-Democratic politicians, new left activists demanded that the Democratic Party democratize its internal processes.

Here, in short, was a thoroughgoing critique of statism, advanced not by the right, but by young Black and White activist/intellectuals devoted to a decentralizing, devolutionary, radical-democratic politics.

We in the new left assumed that the corporate-liberal model was the only viable framework for sustaining modern capitalism. We assumed that laissez-faire capitalism was a thing of the past, that economic growth could now be permanently engineered by the corporate state, and that a sense of social responsibility was prevalent among corporate managers. And so, we tended to believe, the welfare state did not need defense from the left — our job was to present its conservative functions in dampening social unrest, expanding consumer markets, and undermining class consciousness. The benefits of corporate liberalism for the wider population were assumed by new leftists to be well-established. Our goal was to undertake its critique and try to create alternatives.

Over the past 25 years, however, this radical-democratic impulse of the New left has been lost.

The explanation of that loss begins in the early 1970s, when the fiscal crisis of the state turned corporate elite consensus against The Model. With corporate profits shrinking under the pressure of global economic competition, elite consensus shifted toward the need to free capital for global opportunities. That meant a lowering of living standards and expectations for American workers, as well as a reduction in state efforts to channel investment for domestic purposes. It was the corporate-liberal state — not laissez-faire — that was obsolete.

Meanwhile, thousands of new leftists who, in the 60s had experienced a moment of apocalyptic possibility and danger, were discovering ways to join politics with commitments to family and vocation. Many found niches in academia; others in professional fields — social work, planning, health, law, school teaching. Many created alternative cultural projects — community newspapers, radio stations, film collectives. Others became organizers in community-based organizations, unions, and non-profit agencies.

The result was considerable ferment at America’s grassroots, crystallized in the “new social movements” of environmental, feminist, consumer, and cultural activism. This new localism had a political strategy: activists aimed at gaining local power at the polls, challenging the dominance of traditional community elites, and pursuing local political experiments. A national strategy seemed premature.

But by the late 70s , some glimmerings of a national strategy were evident. European efforts to renew social democracy under the banners of Eurocommunism and Eurosocialism suggested that a new model for post-capitalist development might be emerging: a revitalized democratic socialism, with an emphasis on “economic democracy.” Economic democracy as program and strategy was linked to, and inspired by, a loosely coordinated “citizen action” movement at the grassroots. The localism of 70s activists had helped spark a variety of efforts to organize middle and working-class communities on behalf of consumer interests and neighborhood preservation. Struggles for rent control, for utility rate control, against urban development and plant closings that threatened neighborhoods and towns, against bank and insurance red-lining — all these grassroots efforts fit within the emerging imagery of economic democracy. So did the projects of Ralph Nader — which aimed at creating a consumer movement against predatory corporate practices — and much of the rapidly-building environmental movement. By the late 70s it appeared that the organizational and intellectual bases for a new national left politics were coming into being in a movement for economic democracy. Economic democracy sought to go beyond traditional welfare state and conventional liberal perspectives, by stressing not only the provision of state subsidies for a social wage and a safety net, but the use of Federal law and resources to encourage community, worker, and consumer empowerment.

Then came the 1980 election. Legions of blue-collar voters in the Rust Belt defected from the Democrats to protest their failure to deal with economic insecurity and unemployment. The Reagan presidency quickly put leftists on the defensive, and dashed most of the 70s talk about economic democracy and a post-welfare state radicalism. Reagan’s effort to dismantle the welfare state and the public sector, and his focused effort to weaken the power and lower the living standards of workers, drove the left to defensive politics. Instead of continuing their critique of bureaucratic government and labor unions, activists sought to protect the welfare state from the new offensive. After all, the communities and constituencies with whom they worked and lived depended for their survival on the social safety net, living wage, and corporate-government-labor partnership — and the permanence of these was now in doubt.

Meanwhile, the assumption that neo-socialist models were taking form in Europe proved to be false. The traditional social base for the European socialist and communist parties was eroding. And then came the cataclysmic collapse of Communist Party rule in Eastern Europe and the crackup of the Soviet state. The end of communism was enormously exhilarating to democratic socialists in Europe and the United States: it seemed to validate our belief in the creative potential of grassroots democratic movement. But instead of providing impetus for creating a third way between state socialism and corporate capitalism, post-Communist development in these countries seemed to be governed by a purely market-driven logic. In short, by the end of the 80s, all existing models of left politics in the world had disintegrated or been badly undermined.

At the same time, radical intellectuals turned inward, and devoted large amounts of energy to academic discourse and campus-based conflicts, and to an “identity politics” aimed at creating modes of expression for hitherto subordinated, denied, or disvalued social categories and cultural traditions. With established structures of authority unresponsive, the social surplus available for creating collective goods severely diminished, and all alternative democratic models apparently discredited, many of us quite naturally found cultural critique, artistic expression, and the nourishing of identity more fulfilling than stale politics-as-usual.

Over the last 15 years, then, American leftists have increasingly drifted without a sense of strategy or long-term direction, and increasingly acted as defenders of the status quo — aiming to ward off threats to undermine rights and entitlements won in past struggles.

Globalization

Why have the assumptions and models of left-wing political strategy disintegrated? The heart of the problem is that the globalization of the political economy has undermined the national state. This undermining has had profound implications for a state-centered left.

The left has, to be sure, never been close to achieving its larger hopes for social transformation through national politics. Social democrats in power could establish the social wage and mitigate the human costs of laissez-faire capitalism, but were never able to prevent capital flight and disinvestment which destabilized their economies, and thwarted their more far-reaching plans. Capital has always been more mobile and its owners more elusive than state power could manage. Still, left parties and mobilizations did have sizable effects on creating basic standards for a decent life.

The current crisis is qualitatively new. The mobility of capital is now so free and easy — and the capacities for corporate flexibility so considerable — that individual nation-states have lost control of their economic destinies. As a result, there is no way for nationally-based political movements and nationally-oriented political programs to induce or compel capital to go where its owners don’t wish to go or do what they are not inclined to do. Accordingly, government as we have known it can no longer represent the basic needs of people without property for some security, for a decent living standard — even if Debs’ dream of a working class-based party in charge of government were realized.

Moreover, in the global economy, corporate elites no longer care very much about the American domestic society and therefore have no particular will to overcome the political and ideological resistance of smaller business and the Republicans. Even a mild degree of regulation, redistribution, and increased government authority to control investment decisions runs afoul of the desire of private capital to be as free as possible to operate globally, and the felt need of corporations — both large and small — to reduce their wage bills.

If American political and corporate elites continue to resist any semblance of welfare state-Keynesian social policy, the conditions of life for the majority of Americans will continue to deteriorate. Real wages will decline. Job insecurity will worsen. The social wage and the safety net will shrivel, along with the quality of education, urban life, and social services. Environmental degradation will accelerate. Social polarization and conflict will intensify. The commercialization — and dumbing down — of culture will be ever more pervasive, while the space for creative cultural expression will narrow.

Is this deterioration inevitable in the new global economy? Yes, if the present structure of power and the social priorities that flow from it remain undisturbed. The immediate political challenge for American liberals and progressives is to modify those priorities and ensure a more equitable distribution of the costs of globalization. But the experience of the past three years teaches us that a Democratic administration does not have the power fundamentally to change priorities. Collective resistance to unjust distribution is the only way to compel state action that will enforce some degree of equity and social decency. Mass action that threatened the social fabric and destabilized institutional authority forced democratic reform in the 30s and 60s; a similar resurgence of protest is the only way to restore equitable social policy now. But such resistance won’t happen spontaneously as a result of grievance and anger. It requires the initiative of organizers and activists. Since Debs, the most important historical role of left-wing activists has been such movement-building. Since Debs, to the extent that public policy has served goals of equity, expanded the social wage and social investment, and enhanced rights of self-organization, it is because the American state has had to respond to the organized demands of disadvantaged groups, mobilized with the aid of committed activists, and active both in the streets and at the ballot box.

To win support, however, a revived progressive activism must have a constructive agenda and a strategy guided by it. Although the defensive action that currently dominates activist energy may have some beneficial results, relatively marginal political shifts will, by themselves, not substantially change the distribution of power or pain in the country. To make such change possible, we need to develop a more far-reaching program and pursue it aggressively.

A Progressive Agenda

What, then, would a Progressive Agenda look like? In general terms, it would need to excite grassroots activism, appeal to popular majorities, and, if implemented, provide means for people to defend their living standards and improve their life chances in the face of globalization. More specifically, it might include the following elements (see Sidebar for summary):

1. Expand the Social Wage. A new left politics can’t rely on New Deal-style programs. But with private wages declining and job security vanishing, hopes for maintaining decent living standards still depend on collective goods and subsidized services. The most crucial such good remains universal health care based on the single-payer model (see John Canham-Clyne, David Him- melstein, and Steffie Woolhandler, “A Rational Option,” Boston Review, October/November 1995). But implementing that model will require a confrontation with the power of the insurance industry and a degree of popular mobilization that hasn’t been tried.

Passage of a universal health care program would complete the old New Deal/welfare state agenda — decades late. But the state fiscal crisis and current political climate mean that major spending initiatives at a national level must be accompanied by substantial budgetary restructuring. To achieve that, we need a major reduction in the military budget; a conversion strategy that focuses on job creation and environmental sustainability; and a progressive tax reform that raises new revenue by plugging corporate welfare loopholes.

2. Expand Community Power. The most important vision democratic activists have to offer in the globalized economy is that of self-determining communities — communities with the power to plan their own development and the resources to fulfill those plans. In this vision, the state is not the source of direction, but of the rules and some of the capital that supports and nourishes local initiative.

For the past 25 years, many of us have been implementing such a vision in our community and institutional work. When corporate decisions threaten economic loss and social dislocation, community-based mobilization has been an increasingly frequent–and often surprisingly effective–response. Struggles to prevent or mitigate plant closings and relocations, reduce industrial pollution, and prevent destructive development have become central elements of local politics. Out of local resistance have often come community and institution-building initiatives that offer important leads about social reconstruction in the era of globalization.

Resistance to toxic pollution spawned national networks for environmental justice and sustainable production that now have links to the emerging international environmental movement. Resistance to plant closings has, in some communities, laid the groundwork for comprehensive community development plans and strategies. Grassroots environmental activists work to find job-creating alternatives to corporate land and resource exploitation. Neighborhood organizers in central cities devise community development plans that try to combine needs for housing and social services with local job-creation efforts. Education activists create new community schools on the 20/20 Principle: no school bigger than 20 classes, no class bigger than 20 pupils. Neighborhood-based health care, child care, mental health centers and other social services continue to provide models for community self-determination.

In the United States, a growing body of public law and rule-making provides the beginnings of a legal foundation for community empowerment. For example, state and national environmental legislation adopted over the last 25 years has created rights previously unavailable for local movements to challenge proposed developments because of their environmental impacts. Campaigns to win similar legal protection for communities threatened with economic disruption–for example, efforts to regulate plant closings, as well as bank and insurance red-lining– point toward com- munity regulation of economic decisions. Instead of demand- ing increased federal regulation administered by top-down bureaucracy, the logic of these rules is to provide for community voice in corpor- ate decisions through mechanisms of public accountability, open hearings, and corporate negotiation with local government and community organizations.

Communities also need access to capital for local investment–capital often unavailable from conventional, private sources of finance. A fundamental progressive strategy for protecting living standards depends on capturing capital and power to launch community economic development plans. I refer here not to the commonplace and often disastrous efforts by communities to invite their own rape by corpor- ations and developers through tax write-offs and corporate subsidies, but to efforts to develop community investment in and ownership of enterprises that create jobs and provide local means for providing food, shelter, health care, and other necessities so that adequate living standards can be sustained in the face of uncertain private wages.2

In short, a Progressive Agenda would center on national legislation to empower localities — national rules for community voice, and national resources to support community planning, development, ownership, and control aimed at sustainable local and regional economies.

3. Democratize Institutions. The global market and the decline of the state compel the restructuring of private and public institutions. When carried out from above, corporate and bureaucratic downsizing are designed to protect the incomes and perquisites of those at the top, while imposing costs on those with least power. Within organizations, the result is fear, demoralization, and resentment. In the larger society, increasing economic insecurity and dislocation for previously comfortable middle layers accompanies further degradation of the poorest. In the name of efficiency, environmental protections are threatened, fringe benefits liquidated, and all the institutional “frills” that make up a reasonably varied daily life are abolished.

The alternative is to enable all of the constituencies of a given institution–workplace, school, government bureaucracy–to participate in the processes of institutional change. The first principle of workplace democracy is to fully guarantee the right of employees to form effective unions without fear of reprisal, and strike without fear of replacement. But the traditional domain of collective bargaining must be opened up to include the entire scope of decision-making that affects the security, well-being, and fulfillment of employees. This means the development of institutional mechanisms of democratic representation, voice and accountability, open books, and the diffusion of expert knowledge.

A new Progressive Agenda for national legislation, then, would have as a priority labor law reform that protects workers’ rights to unionize, strike, and bargain collectively. The goal of workplace democracy depends on workplace demands and struggles led by a revitalized labor movement, but proposals for federal chartering of corporations, including provisions for workers’ rights and voice, deserve serious discussion as a means to support such struggles.

4.Restructure Work. Freeing people from alienated labor was once a cornerstone of radical action. So it is striking to realize that the American labor movement has not focused on the issue of work time for decades. European labor unions have achieved some reduction in work time, seeing this as part of a strategy for protecting jobs — and the issue is very much alive in several countries. Workers in the advanced societies need to be able to examine and debate the shorter work week as a means to sharing work that would also free time for citizen participation and community service. How might reductions in work time be accomplished without destruction of living standards? Would reallocation of work time actually create significant numbers of new jobs? Can the social wage and collective goods be substituted for job-related wages while sustaining adequate living standards? Can definitions of “paid work” be expanded to include the full range of caring and helping now required of families and volunteers?

Reconsidering the connections between work and income, and the meaning of work time, is a crucial role for left intellectuals and activists. Meanwhile, shorter-term strategies for job preservation and creation rest on the fate of comprehensive community development efforts; conversion; expanding the need for teachers and child-care workers created by new investment in smaller classes and in affordable daycare; investing in recycling, conservation and soft-energy alternatives; and investing in infrastructure development and affordable housing. Each of these expansions of traditional welfare state programs would have potential political appeal because they would deal with urgent social needs, while creating meaningful job opportunities.

5. Establish a New Internationalism. Resistance in the global age begins with protectionist impulses. Protectionism resists economic changes that threaten the wages and well-being of relatively well-off sectors of the working class. Obviously, such resistance can turn nativist and exclusionist. The alternative is to support improved living standards for workers in the poor countries. How? The most direct way would be for American labor organizers to provide direct assistance to struggles in those countries to which jobs and capital are being exported, perhaps through concerted action in support of such struggles — sympathetic demonstrations, political action, and job action. Environmental internationalism–already evident in growing international networks of environmental activists and global environmental conferences — provides an equally important track for strategic internationalism.

Historically, American workers’ living standards were enhanced by US neo-colonialist relations to the third world. Today, the American population is being colonized by the same supranational forces as the rest of the planet, and American elites can no longer credibly promise American workers that they will be advantaged in the global economy. The increasing congruence of interests between workers of the North and South provides a material basis for a new internationalist consciousness — as does the wave of new immigration to the United States from the South.

The alternative to the current “race to the bottom” is to couple grassroots internationalism with a campaign for a global charter that establishes international labor and environmental standards as enforceable features of international trade agreements (for debate on the value of such standards, see the articles by Alice Amsden and Richard Rothstein in this issue of Boston Review).

6. Democratize Elections. Across the country, electorally-oriented progressives, frustrated with the corporate lock on government, are trying to find strategies to break that control and foster independent political action. But existing electoral rules marginalize progressive third-party efforts — except in some non-partisan local races. Some advocate a widespread effort to remake election procedures — to permit “fusion” (enabling third parties to endorse acceptable candidates of other parties), and to create forms of proportional representation (thereby allowing minority parties chances to gain entry into legislatures). Organizers’ instincts rebel against “procedural” campaigns which seem to be remote from everyday interests and are complicated and boring to explain — so it is hard to argue in favor of making electoral reform a high priority. On the other hand, the sweeping success of “term limits” suggests that electoral reform that gives us more choice (a real political free market?) is worth experimenting with. The most savvy center for such experiment is the New Party, which is having success in non-partisan elections while attempting to institute a bottom-up effort to create a progressive new party that has the legal right to endorse progressive Democrats in partisan races.3

Meanwhile, it is clear that a national drive for authentic campaign finance reform that would end the influence of corporate political wealth on state and national government, and enable political campaigns to be conducted in an atmosphere of democratic debate (through restriction on campaign commercials and set-asides of television time for campaigning and debate), would have wide popularity. Support for such reform appears to be the main tie that binds Perot’s constituency; and most polls indicate strong popular support for reform efforts. The fact that Republican and Democratic leadership have no real interest in such reform creates a vacuum that progressive activism could fill.

A National Alliance?

The fast route to advancing such programs and strategies would be for the leadership of major national, progressive organizations to meet and adopt a common programmatic and strategic agenda: I’m imagining an alliance linking progressive unions, NOW and other major feminist organizations, the NAACP and other minority and civil rights organizations, the Sierra Club and other environmental organizations, Citizen Action and other political reform groups, liberal religious organizations, The Rainbow Coalition, and the host of other progressive lobbies and organizations based mainly in Washington. These groups have active, or potentially active, grassroots memberships in the tens of thousands; many have large direct-mail donor bases. All have politically sophisticated and experienced staffs, and small armies of young interns. A joint decision by national leaderships to support and mobilize for a shared Progressive Agenda would energize grassroots progressives, providing them with a sense of direction and hope. At the same time, such a formation would help to force debate on national priorities, and on how the costs and benefits of global restructuring are to be distributed. It would present a serious alternative to nationalist and exclusionist rhetoric, and restore a left voice in national discourse and grassroots action. And in so doing, it would emphasize that a new progressive politics will be as much radical-democratic as social-democratic: that it will not rest principally on the Federal budget and bureaucracies, but on decentralizing power, fostering grassroots energy, and encouraging democratic participation.

Here, then, is a question for immediate and urgent discussion: if such a national coalition strategy is plausible and promising, why isn’t it already being advanced by the main liberal/progressive national organizations?

In part because national liberal/left structures are so bureaucratically mired, so protective of organizational turf, so locked into knee-jerk routine, so afraid of jeopardizing their “access,” or scaring off their donor base, or “moving ahead” of their memberships that the notion of launching an independent political coalition doesn’t seem to show up on their screens. But it is hard to understand how these leaderships expect to survive without undertaking some such departure.

As we wait hopefully for national leadership, progressives, meanwhile, need to begin discussion of positive programmatic alternatives, get informed about initiatives already in process, begin some local strategic initiatives that transcend the merely defensive and ad hoc. At the same time, we need to forcefully confront the defaults and abdications of the national progressive structures that depend on our donations and dues and yet seem more and more limited as vehicles that represent our needs and interests.

In Conclusion

The left tradition is not only still alive; paradoxically, its oldest visions are now newly relevant. Radical democracy, the end of “wage-slavery,” internationalism were, in Debs’ day, the acme of utopian vision — inspiring radical commitment, but always postponed by day-to-day struggles for bread-and-butter. Today, it seems, they are not utopian at all — but essential ingredients for a new left program and strategy that goes beyond short-term defense.

The 100-year effort to create a left party is over and failed. No single organization can ever again claim to speak for the “working class” or the “people.” The work of democratic reconstruction requires decentered, pluralistic experiments of thought and action. Activist commitment will be energized by a wide array of contradictory ideological tendencies, religious faiths, and cultural identifications.

To overcome fragmentation and launch grassroots social movements, progressive activists and intellectuals need organizational means of coordination. But the format we need is not a party of the old type. We need frameworks that bring activists and organizers together with each other and with intellectuals in a way that nurtures the sharing of knowledge, the voluntary coordination of work, and the opportunity for mutual criticism, inspiration, and support. In developing such frameworks, we need to focus less on what divides us, and more on the possibilities for a shared strategy for reviving democratic and egalitarian options again in mainstream political discourse.

Debates within the left on problems of race and gender, and issues of environmentalism and communitarianism, must continue.4 But the chances for a democratic option depend on our capacity as activists/intellectuals to look beyond our particular identities and institutionalized niches. Finding common moral ground is, after all, part of what democracy is about. And pursuing a strategy that anticipates the democratic world we wish to create seems now to be a practical necessity.