This forum appears in print in Can the Democrats Win?.

A dramatic transformation has taken place in the U.S. Democratic Party. For several decades it was moving rightward on economic issues, following the same trend as many center-left parties in wealthy democracies. But over the past few years it has made a sharp U-turn, boldly embracing broad and costly economic programs, industrial policy, and active regulation. Indeed, in 2021 Democrats pursued the most ambitious and redistributive economic agenda their party has attempted in more than half a century. Contrary to frequent denunciations of Democratic “wokeness” (whether from the right or the left), economic issues—not cultural ones—have become the core of the party’s agenda.

This shift is surprising because of another striking development: Democrats have simultaneously sought out and won over an increasing share of affluent suburban voters—the very voters who might be expected to oppose bold redistribution and constrain the party’s economic ambitions. Now, more than ever, the Democrats’ racially diverse electoral coalition is a mix of the affluent and economically struggling.

What explains these changes, and what do they mean for the future of the party and the nation? Given the alarming rise of authoritarianism on the political right, the stakes are high—for democracy, not just Democrats. In the aftermath of January 6, the ability of the United States to resist the threat of democratic backsliding seems to rest almost entirely on the electoral success of the Democratic Party. As the 2024 elections approach, few questions are more fundamental than whether Democrats can build and hold together a broad multiracial and cross-class coalition.

The Density Divide and the Brahmin Left

The place to begin is the changing geography of American politics. The partisan divide is now a “density divide.” Over the past few election cycles, Republicans have registered particularly big gains among white voters in lower-density regions of the country battered by the shift to a postindustrial knowledge economy. The consequences of the GOP’s retreat from dense metro areas are now well understood. It has powered the party’s embrace of Christian nationalism and right-wing populism as well as its growing attack on American democracy, leading to a base that is older, whiter, more heavily Evangelical, and less highly educated.

Less well understood is the other half of the story—the transformation of the Democratic Party. Democrats are now firmly established as the political voice of multiracial, cross-class, metro America. Democrats have always done well in urban cores; what has changed over the past several decades is the party’s performance in the suburbs, which have grown more Democratic even as they have grown more affluent. Some of these gains have occurred because the suburbs have diversified racially and economically. Yet the most striking change in recent cycles is growing Democratic margins in the richest suburban communities—the biggest beneficiaries of U.S. economic growth over the last two decades. Most of these areas remain disproportionately white, and many leaned Republican not long ago.

Because of these shifts, Democrats are now much less clearly the party of the “have nots.” In 2021–22, they represented twenty-four of the twenty-five congressional districts with the highest median household income—a striking change from the past. (Documentation for most of the statistics in this piece can be found in a recent academic article we wrote with Amelia Malpas and Sam Zacher.) At the presidential level, Democrats now win counties that produce the lion’s share of the nation’s economic output; some 71 percent of GDP came from the 1 in 6 counties that backed Biden in 2020. Indeed Biden won every one of the twenty-four most economically productive metro areas, and forty-three of the top fifty.

The result is a pronounced U-shaped coalition. On one side are voters driving the party’s recent suburban gains: highly educated and mostly white workers thriving in the knowledge economy. On the other side are less affluent denizens of metro America, disproportionately workers of color and their families, who have limited access to high-wage knowledge sectors. These voters struggle with rising metro costs—especially housing costs—even as they are effectively excluded from the wealthiest, highest-opportunity suburbs.

In remaking their coalition to bring in affluent college-educated voters, Democrats are hardly alone. Left-of-center parties in most other rich democracies have evolved along broadly similar lines as the knowledge economy has built up steam—gaining highly educated professionals while losing white working-class voters, who increasingly embrace the populist right. In economist Thomas Piketty’s evocative depiction, parties that were once oriented toward the working class—the British Labor Party, the French Socialists, the German Social Democrats, as well as the U.S. Democratic Party—now represent the “Brahmin left.” In their efforts to court the affluent and educated, Piketty maintains, these left parties have retreated from their historical commitment to redistribution.

This argument echoes the claims of many American observers, including prominent journalists and analysts such as David Leonhardt, Thomas Frank, Thomas Edsall, John Judis, and Ruy Teixeira. In their recent book Where Have All the Democrats Gone? (2023), for example, Judis and Teixeira lament that the party has “steadily lost the allegiance of ‘everyday Americans’” and that the “main problem” is its “cultural insularity and arrogance.” Democrats, these critics insist, have embraced the social liberalism of their affluent, college-educated white voters at the expense of the working class. Many political scientists would concur that as the class heterogeneity of a party’s coalition increases, it is rational for the party to pivot away from economic issues. At a minimum, a party attempting to appeal to affluent professionals should be expected to mute calls for redistribution and higher taxation.

This logic is reinforced by the fact that in the U.S. electoral system, the density divide carries a “density tax.” As political scientist Jonathan Rodden documents in Why Cities Lose (2019), our first-past-the-post, single-member electoral districts badly disadvantage the geographically concentrated Democrats. In this system, votes for geographically dispersed Republicans are more efficiently distributed.

The problem is especially acute in the Senate, with its extreme skew in favor of low-population states. Senate Republicans have not represented a majority of voters since 1996, but they have held a majority of Senate seats for about half that period. This has proved crucial to Republican efforts to confirm conservative Supreme Court justices, as have the biases of the Electoral College (which hurts Democrats in part because of the density tax). There is no clearer marker of the GOP’s built-in advantages than the fact that Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections, while Republicans have chosen six of the nine members of the Supreme Court.

The density tax also carries over to the House and to state legislatures, where the Democrats’ spatial concentration also leads to many wasted votes—and since state legislatures play a powerful role in drawing state and federal districts, the density tax is compounded by gerrymandering. At the extreme, as in Wisconsin, a minority of votes can be turned into not just a legislative majority but a veto-proof supermajority.

The density tax thus increases pressure for economic moderation. Competing on a tilted playing field, Democrats badly need upscale suburban votes in less densely populated metro peripheries. More broadly, they have to reach well past the center of the electorate to obtain legislative majorities. Combined with the party’s move up the income distribution, this harsh reality has been widely seen as closing the door on ambitious economic reforms.

And indeed, it did—for a time. From the mid-1980s to the end of Barack Obama’s administration, the Democratic Party largely fit this pattern. Political historians have documented how, as Democrats moved into the suburbs, the party moderated on class issues while highlighting social issues like abortion rights that appealed to affluent professionals. Lily Geismer and Matthew Lassiter, for example, describe a “deliberate, long-term strategy by the Democratic Party to favor the financial interests and social values of affluent white suburban families and high-tech corporations over the priorities of unions and the economic needs of middle-income and poor residents of all races.”

The party’s shift was also driven by the sharp change in the balance of economic power that had been underway since the mid-1970s. Economic inequality began its long upward climb, unions weakened dramatically, and the business community undertook an unprecedented political mobilization. The Democratic Leadership Council, founded in 1985 by Al From, sought to pull the party rightward on economics, weakening its attachment to organized labor and strengthening ties to the business community.

The rightward pivot stuck. Aside from Bill Clinton’s failed effort to overhaul America’s highly dysfunctional system of health financing, the self-declared New Democrat tacked rightward, emphasizing deficit reduction and accepting a punitive welfare reform plan. Most consequential of all, he fully embraced the agenda of fiscal restraint, free trade with little compensatory redistribution, and financial deregulation that was fatefully sweeping both Wall Street and Washington. “Rubinomics” became the trademark of Clinton’s economic team, led by financier Robert Rubin and Larry Summers.

Summers’s place on Obama’s economic team signaled the considerable continuity in Democratic policymaking from the Clinton years. Obama’s first two years in office featured significant reforms—notably, a major health care bill (which still fell well short of the universal models found abroad). But they were marred by an anemic recovery package advocated by Summers that left the economy weak for years. After 2010, the president mostly played defense against a resurgent congressional GOP and cultivated an “Obama coalition” of minority voters and affluent professionals, further building up the party’s U-shaped base. Meanwhile, his focus on reaching a bipartisan deficit-reduction agreement broadcast the resilience of the Brahmin left.

Bigger, Bolder, Broader

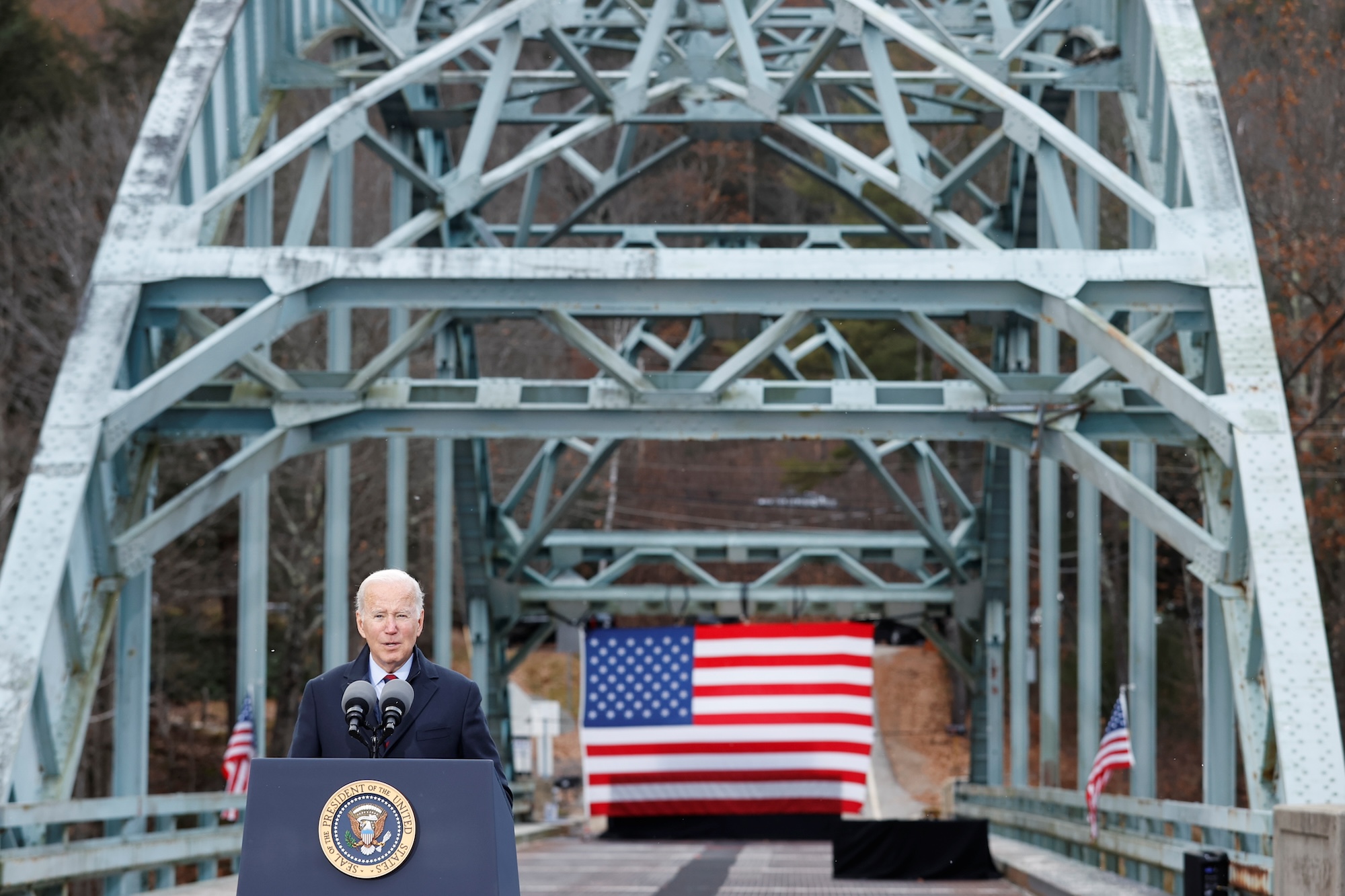

Fast-forward to the Biden administration, however, and the party’s economic approach looks very different. The “Blue Divide” within Democrats’ U-shaped electoral base might have pushed against a big redistributive agenda, but instead Democrats embraced one. Whether the metric is levels of spending or reliance on active government, Biden and his congressional allies have been far bolder on these issues than other recent Democratic administrations. No less striking, these efforts have dominated not just legislative and executive policymaking but also the party’s rhetoric. In recent national platforms, as well as the social media appeals of both the party’s leadership and rank-and-file congressional Democrats, economic issues have had pride of place.

The surprise isn’t just that Democrats tacked left on economics even as they have successfully courted affluent suburbanites. It’s also that they have done so with the slimmest of margins in Congress. The density tax has mattered here. In 2021 Democratic senators—plus the two independents who caucus with them, Bernie Sanders and Angus King—represented over 56 percent of the nation’s voters but held exactly 50 percent of the seats. With an equally divided and highly polarized Senate, Democrats who hoped to push through new legislation on climate, infrastructure, social policy, health care, and many other economic priorities could lose none of their caucus members in the upper chamber, and only a handful in the House.

The pivotal vote in the Senate belonged to Joe Manchin, whose home state Donald Trump carried in 2020 by a margin of 39 points. Along with Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema, Manchin would ultimately block the bulk of the Democrats’ economic agenda. Yet this outcome has overshadowed the striking fact that the overwhelming majority of the Democratic caucus in both the House and Senate broke sharply with the economic orientations of Clinton-era Democrats. It is this majority—not Manchin and Sinema—who reveal the shape of the emerging Democratic coalition and its policy aspirations.

Much of the 2021 agenda was packaged in the Biden administration’s announcement that spring of two initiatives grouped under the rubric of Build Back Better (BBB): the American Jobs Plan, focusing on infrastructure, and the American Families Plan, focusing on education, health, and family policies. BBB might well have stood for Bigger, Bolder, Broader. Even a fairly detailed summary of these two initiatives—which hardly exhaust Democrats’ agenda in 2021–22—would omit provisions that would have been considered landmark policy changes if enacted on their own in the recent past.

The American Jobs Plan called for $2 trillion in new spending over eight years—approximately 1 percent of GDP per year. The plan included over half a trillion dollars in infrastructure spending on roads, bridges, ports, rail systems, and mass transit, as well as spending for “human infrastructure”—home- and community-based health and elder care. It contained unprecedented investments in green and high tech manufacturing, affordable housing, research and development, the electricity grid, and the installation of high-speed broadband around the country. In a major break with decades of Democratic policy, these proposals embraced industrial policy, including requirements or incentives for U.S.-made materials and high labor standards. Like many other elements of the plan, these measures were designed to generate higher-quality jobs that do not require a college degree, boosting wages and expanding opportunities to unionize. Throughout the 2021–22 economic agenda, redistribution through public taxes and transfers went hand-in-hand with predistribution—reducing inequality in the market itself—through public investments and regulations and efforts to encourage unions.

The American Families Plan was at least as ambitious. It outlined a very large expansion of the welfare state at an estimated cost of $1.8 trillion over ten years. Its proposals would have improved access and affordability of education (two years of free community college, considerably more generous Pell Grants) and health care (extension of Affordable Care Act subsidies, expanded eligibility for Medicaid, notable improvements to Medicare).

True to its name, the American Families Plan also promised a dramatic expansion of family policies, envisioning a rapid transformation of a policy domain where the United States had long been a conspicuous laggard among wealthy nations. It called for two years of universal pre-K and included a major new program of child care subsidies (income-tested, but reaching far into the middle class), along with support for better pay for child care workers. It also introduced a new federal program offering paid family and medical leave. These initiatives alone were projected to cost $650 billion over ten years. But here again the price tag does not convey the full picture. In both public and private, policymakers spoke of remaking the “care economy” into a sector in which workers—disproportionately women workers of color—had better pay, training, and opportunities for unionization as government boosted demand for their services.

What’s more, the American Families Plan called, in effect, for making pandemic relief adjustments to the child tax credit (CTC) contained in the early-2021 American Rescue Plan permanent. The plan slated the generous new levels of these credits to expire in 2025, though Democrats clearly hoped they would be able to keep moving that date back once voters became accustomed to receiving the benefit. Between 2020 and 2021, along with other relief measures, changes to the CTC cut child poverty by a remarkable 40 percent, and the biggest reductions occurred in Black and Hispanic households. This policy proposal was thus a signal example of a strategy underlying many of the Democrats’ economic initiatives: broad programs that would nonetheless have disproportionately large positive effects for racial and ethnic minorities.

In combination, these proposals constituted the most extensive package of economic benefits for working- and middle-class families the Democrats had proposed since at least the 1960s. As a share of GDP, Biden’s full set of proposals was more than twice as large as Clinton’s in 1993 and around 80 percent larger than Obama’s in 2009.

Ted Fertik & Tim Sahay say:

“Hacker and Pierson somehow manage not to mention China at all.”

The Biden administration also veered left in important regulatory domains. Perhaps the clearest is its embrace of a more vigorous stance on antitrust issues, signaled by the appointment of Lina Khan to head the Federal Trade Commission. Khan’s ambition to tackle corporate concentration and unequal market power was aided by fellow legal academic Sabeel Rahman, who—as acting head of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in 2023—rewrote cost-benefit rules that had tilted the deck against more active regulation in fields as diverse as environmental and climate policy and financial and consumer protection. Khan and Rahman were not outliers in the Biden administration; virtually every regulatory agency was encouraged and empowered to do more.

There is good reporting suggesting that leading Democrats in both Congress and the administration were confident throughout most of the extended legislative negotiations that Manchin and Sinema would ultimately agree to something close to the roughly $2 trillion BBB bill that passed in the House in late 2021 (which consolidated and trimmed down the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan). In the end, pointing to the threat of high inflation, Manchin accepted only about a quarter of that amount. This meant jettisoning most of BBB’s redistributive elements—ironically, elements that would have been enormously beneficial to the nation’s poorest states, like Manchin’s West Virginia. What was left, embodied in the Inflation Reduction Act and two bipartisan bills, are still significant wins: truly important climate initiatives, some improvements of the Affordable Care Act, modest increases in tax revenues from corporations and the wealthy, and some new investments in infrastructure and research and development.

What’s Going On?

The unexpected transformation of the Democratic Party is puzzling in two ways. First, there’s the why question: Why has it changed course? Equally puzzling is the how question: How has it been able to do so without alienating the affluent suburbanites now critical to its electoral coalition?

Start with the second question. Among those who thought that Biden’s emerging coalition was vulnerable was Trump himself. In a clear effort to drive a wedge between the Democrats’ suburban and urban voters, he issued a racialized refrain in battleground state after battleground state in 2020. In the Wall Street Journal, he and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson asserted that Democrats would “make sure there is no escape” from “the crime and chaos in Democrat-run cities.”

The strategy didn’t work—in part because Trump was the wrong messenger, but also because the Democrats’ U-shaped voting base has stronger bonds, including shared interests and values, than many assume. There’s a growing body of evidence that metro areas that are economically interconnected foster not only innovation and prosperity but also some level of common interest and understanding across class lines. Even in the United States, where fiscal fragmentation and residential segregation are unusually extreme, affluent metro voters may well support—or at least not oppose—considerable spending and redistribution to improve the economic environment or quality of life of the places where they live.

Of course, this support has real limits. Perhaps the most potent concern is taxes. As the Democratic coalition reaches into higher income deciles, the party brings in voters who might worry they will have to foot the bill for expensive new programs. Democratic elites clearly recognize this risk. In his 2020 campaign Biden pledged to avoid raising taxes on households with annual incomes below $400,000—a figure significantly higher than the cutoff Obama promised in his 2008 run ($250,000, or around $300,000 in 2020 dollars), and one that essentially ruled out new taxes on all but the richest 2 percent of Americans.

Still, the magnitude of this constraint can easily be overstated. Thanks, ironically, to the incredible concentration of wealth and income in the United States, the revenues needed to pursue an ambitious economic agenda can come exclusively from corporations and the very rich, at least in the short- to medium-term. As a result, Democrats do not have to tax most top-decile households to raise substantial sums, and indeed their 2021 plans—costing more than $4 trillion over ten years in their most expansive form—honored Biden’s $400,000 threshold, with much of their financing linked to repealing 2017 GOP tax cuts. The party’s reluctance to tax all but the very rich has real costs; it makes contributory social insurance programs like Social Security—wildly popular and long the party’s signature—nearly impossible to design, and it will be hard to sustain indefinitely, especially if Democrats manage to reduce inequality. But for now, they can credibly propose more spending for everyone while promising to protect all but the richest voters from higher taxes.

Potential ethnic and racial divisions within the Democrats’ new base may be harder to sidestep. Democratic politicians now win a substantial majority of Black, Latino, Asian, and other voters of color, and the growth of racial liberalism among white Democratic voters has made it easier for Democratic elites to manage their multiracial, multi-ethnic coalition. Yet especially among pivotal blocs of moderate white voters, there is still potential for a backlash to rhetoric and an agenda that heavily emphasizes racial inequalities. Steve Bannon understood this potential when he said in 2017 that he wanted Democrats “to talk about racism every day.”

These risks intersect with a closely related danger: the fraught politics of local control within America’s highly segregated metro areas. In their Wall Street Journal op-ed, Trump and Carson warned that Biden could end restrictive residential zoning—a key source of suburban privilege, since it limits the ability of poorer residents to access resources in these communities. Such “opportunity hoarding” not only hurts lower-income and minority households; it is also a big cause of skyrocketing housing costs in metro America—the greatest threat to the continued success of high-growth urban hubs. Affluent metro dwellers are highly protective of these arrangements even when they profess economically and racially progressive values. Challenging them would likely activate deep class and racial divisions within the Democratic electorate.

Fortunately for Democratic leaders—but not for those who suffer from these inegalitarian policies—the core arrangements that give rise to opportunity hoarding are largely managed at the local level and are widely perceived to be local responsibilities. In other words, the localized, low-profile character of these policies facilitates the national party’s efforts to keep them far from its core agenda, despite the profoundly negative effects that opportunity hoarding has on the Democrats’ less affluent voters.

This brings us to the most critical point about how Democrats have managed the growing Blue Divide: in our highly polarized two-party system, party leaders have considerable capacity to develop positions and policies that sidestep genuinely divisive matters. Because issues are complex, and responsibility for policy outcomes frequently unclear, party elites can often set agendas without risking election-swinging backlash from voters—particularly their own core voters, who are strongly inclined to stick with them. This is especially true in our current era of “negative” polarization, when voters may be more motivated by their dislike of the other party than their affection for their own. To paraphrase the great political scientist E. E. Schattschneider, Democratic leaders can organize some issues “into” politics while organizing others that threaten to activate internal divisions “out.”

These considerations help explain how the Democratic Party has been able to change, despite the constraints of its new coalition. While growing economic heterogeneity has opened up new potential cleavages and limited the range of economic policies that national leaders have considered feasible, it has neither required nor induced a pivot away from an economic agenda. Instead, Democrats have embraced a certain kind of pocketbook politics—designed to cultivate support by improving the material conditions of a large majority of the country without activating divisions that risk fracturing the party’s metro coalition. This strategy has involved foregrounding substantial redistributive spending, yet doing so in a manner that limits the potential for backlash among affluent suburban voters hostile to taxation or resistant to measures directly focused on racial inequality or opportunity hoarding.

Pressures for Progressivism

What about the why part of the puzzle? Why have Democratic elites chosen to embrace an ambitious redistributive agenda, reversing the pattern of Piketty’s Brahmin left?

A key part of the answer is clearly the increased strength of the party’s progressive wing. The nomination process in our two-party system, where candidates must pass muster with a primary electorate, has built-in potential to amplify the base’s voice. Both Sanders and Elizabeth Warren placed economic populism at the heart of their recent presidential candidacies, and this emphasis is shared among congressional progressives more broadly, as can be seen in their political rhetoric. Along with Amelia Malpas and Sam Zacher, we have explored the messaging of Democratic members of Congress between 2015 and 2023 using large-scale textual analysis, focusing on the communications of national elected officials on Twitter (now X). We found that, among rank-and-file members of Congress, members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus talk the most about the party’s economic proposals on Twitter—an unexpected finding given the frequent assertion that it is the party’s left flank that is marching it toward the cultural left.

Progressives have also begun to challenge “establishment” incumbents in Congress, with contested primaries rising in frequency. While most challengers lose, even the threat of such primary challenges can send a powerful message. And there have been stunning exceptions—especially Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s victory over Joe Crowley, the fourth-ranking Democrat in the House, in 2018. Factional dynamics among Democrats have not been as intense as among Republicans—first the Tea Party and later the Freedom Caucus pressed the GOP to swing hard to the right—but the growing strength and assertiveness of the party’s progressive wing has pressured party leaders and rank-and-file members of Congress to tack left.

Yet it would be a mistake to reduce this pressure to a simple electoral calculus. The universe of organized “policy demanders” in the party has also reoriented, especially following the 2008 financial crisis and the party’s halting response to it. Think tanks like the Roosevelt Institute made the crafting of an alternative economic agenda their core priority, and they wound up providing critical staff to the Biden administration. Moreover, environmental groups and organized labor—too often at loggerheads over the Obama administration’s failed cap-and-trade climate initiative (which promised nothing but pain for most unions)—found much more common ground in the alternative energy–boosting framework of the Green New Deal (made prominent by Ocasio-Cortez). While Biden’s wide-reaching plans remained much more limited than the revolutionary ambitions of the Green New Deal, the framework helped inspire the positive-sum, carrots-not-sticks approach on which it was easier for potential coalition partners to find common ground.

Another causal factor is that demands for social justice initiatives intensified in response to George Floyd’s murder and the multiracial mobilization of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. Women’s groups, key segments of organized labor, and social policy advocates also turned out in support of a much more ambitious “care economy” agenda. Disappointment with the tepid Obama response to the financial crisis and Great Recession has interacted with these changes to shift economic discourse in the party leftward.

Though the precise effect is difficult to calculate, there is little question that COVID-19 also provided critical political momentum. The resulting economic crisis dramatically exposed many of the holes in the American safety net and the degree to which low-income families and workers of color were most likely to fall through them. At the same time, it also revealed the critical importance of their low-wage work, especially in the care economy, and buried (for a time) calls for fiscal restraint. Prior to 2020, the demand for fiscal stimulus probably would have generated outrage.

The significance of these factors—the growing electoral clout of the left, the increasing ambitions of party-affiliated organizations, a leftward turn of the party’s economic experts, and the enormous economic and social shock of COVID-19—were on display before Biden’s election. During the summer of 2020, the Sanders and Biden campaigns came together to form a unity agenda that involved considerable concessions to Sanders’s priorities. Their agreements, heavily focused on economic issues, formed the basis of the 2021 agenda.

The Democrats’ ambitious economic agenda also reflected a deliberate strategy to avoid activating potential schisms within their party over race and ethnicity. Revealingly, party elites put the two most racialized priorities in the Biden-Sanders unity documents—immigration reform and criminal justice reform—on the legislative backburner. In party communications on Twitter, pocketbook concerns were also the dominant focus of elected national Democrats, particularly Biden and the House and Senate leadership (though popular issues like abortion rights also appear, especially after the Dobbs decision in 2022). Indeed, in the 2015-22 period we studied, it was Republican party leaders, not Democratic elites, who invoked cultural themes rather than economic ones, relentlessly broadcasting the image of a “woke” Democratic party.

The potential fragility of the Democratic coalition around racial issues has likely played a critical role in shaping this balance. Since metropolitan-based parties must pay a density tax, obtaining a majority requires reaching well beyond the median voter. Despite the increasing racial liberalism of the Democrats’ electorate, that requirement in turn necessitates fashioning appeals that extend well beyond the community of racial liberals.

A final consideration motivating the party’s leftward turn on economics is the opportunity it has afforded to reach out to white working-class voters. This critical voting bloc had been drifting away from the Democrats over recent decades, but the trend came to a head after 2010. By 2016 a collapse of white working-class support led the party’s “blue wall” in the deindustrializing states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania to crumble, tilting the election to Donald Trump. Biden only slightly improved the party’s performance with these voters in 2020. The following year, the party’s economic agenda was emphasizing the generation of manufacturing jobs and promising to transfer resources from booming metro areas to “left behind” communities that increasingly vote Republican. In Congress, a metro coalition eagerly sought to redistribute money and opportunity to economically disadvantaged parts of the country, only to have the representatives of these areas rebuff them at every turn. But the bulk of Democrats hoped to build power through policy, betting that expansive new programs would rebuild the party’s reputation as a reliable protector of working-class economic interests.

Heather Gautney says:

“Biden’s agenda represents a typical bait and switch.”

A robust but carefully curated economic program thus had an internal and external logic for Democrats. It could help them manage the potential cleavages within their coalition while recapturing some of the white working-class voters they had lost. Rather than directly focusing their agenda on racial justice, which would intensify right-wing media attacks and risk alienating white suburbanites as well as white working-class voters, Democrats built social justice initiatives into their broader economic proposals,with the belief that substantial redistribution itself promotes racial justice. In the context of the Build Back Better push, communities of color stood to benefit disproportionately from initiatives like the CTC, investments in housing and education, and support for the care economy. An unprecedented focus on environmental justice was also part of the Democrats’ climate plans. In short, racial justice issues were built into Democrats’ ambitious policy plans, but in a manner designed to limit controversy and division within the party coalition.

Better Luck Next Time?

Of course, most of the Democrats’ ambitious agenda did not pass. Given this outcome, the evolution of the Democratic Party’s policy ambitions might be dismissed as a nonstory.

Ultimately, that could well turn out to be the case. American political institutions, with their unique system of multiple veto points, are badly skewed against policy reforms. The problem has only become worse with extreme polarization and the now-regularized use of the Senate filibuster. Change is especially difficult if it requires new legislation (by contrast, it only takes five justices on the Supreme Court to change policy dramatically). And it is more difficult still for the Democrats because of the density tax. Windows of opportunity are rare and fleeting, and the window of Biden’s first term just closed.

We won’t hazard a guess on when, and by how much, it might open again. But those who care about saving democracy, overcoming dysfunction, and addressing injustice must play a long game. The work of preparing for the next opportunity must happen now, and in making those preparations, it is important to get the story right about what has been happening to the Democratic Party and the coalition of interests and activists that shape its policy agenda.

Much of the current narrative, with its focus on a party that has either turned away from economics or been cowed by the fiscal conservatism of suburban America, gets the story seriously wrong. 2021–22 was a near miss for a remarkably expansive economic agenda. Led by a president widely regarded as a moderate, the overwhelming majority of congressional Democrats strongly supported a bold set of economic initiatives that represented a clear departure from the policies of the past five decades. These initiatives would have sharply reduced child poverty and cemented an expansive and expensive federal role in the care economy, at long last recognizing the deep gender, class, and racial inequities rooted in a system that that makes raising children and caring for the old and infirm solely a private matter. They promised unprecedented investments in everything from housing and mass transit to higher education and environmental justice. And even the near miss left notable policy achievements on climate, health care, infrastructure, and support for manufacturing.

To build a coalition for their ambitions, Democrats had to manage formidable constraints. A U-shaped party will have a hard time adopting broadly progressive taxation, fashioning new contributory social programs, and addressing racial inequalities deeply embedded in suburbia. And at the moment, big policy initiatives may once again seem a distant possibility. The Republicans who now hold the House are sounding the alarm on debt and deficits, just as they did in 1995 and 2010 (with much of the media once again ignoring that these cries gave way to massive tax cuts for the wealthy at the first political opportunity).

Equally discouraging, there is so far little evidence that the Democrats’ efforts to expand their coalition through ambitious policy have yielded significant political results. Few if any of their initiatives seem to have built power through policy. Even the very large temporary expansion of the child tax credit, for example, seems to have had little impact.

Perhaps time will help; the Affordable Care Act, for example, has become considerably more popular over time. Perhaps change will only come with greater direct investments in building a stronger network of supportive organizations, including labor unions. Or perhaps polarization is now so deeply entrenched—and the media landscape is now so noisy—that the ability of a party to build electoral support through economic governance is severely limited. Indeed, the changing media landscape is probably a major reason why sharply negative perceptions of Democrats are so hard to shake. Both GOP leaders and right-wing commentators relentlessly pillory the Democrats as obsessed with identity and culture. These narratives, amplified through mainstream as well as conservative media, make it extremely difficult for the party to reshape its image, especially when its policy initiatives so often fall victim to congressional gridlock.

But we shouldn’t allow the pronounced (and surprising) change in Democrats’ economic stances to get lost in this noise. Holding together an increasingly diverse coalition while embracing a bold economic agenda was no small feat, and it should not be dismissed simply because it did not complete the perilous institutional obstacle course required by our effectively anti-metro Constitution. Indeed, it is remarkable just how close the agenda came to succeeding. With a slightly stronger Democratic hand in Congress, the agenda of 2021 could be revived. The money will certainly be there—the only benefit of the spectacular transfer of financial resources to corporations and the wealthy over the past generation—and if the electoral shifts we have charted endure, there is a real chance that the political momentum could be as well.

Boston Review is nonprofit and relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate here.