Christopher Street in New York’s West Village was crowded on the second night of the Stonewall uprising, which took place over the weekend of June 27, 1969. People had been drifting in all day to see for themselves the aftermath of the previous night’s fierce resistance to police. They came angry, exhilarated, curious, and wary; they came ready to be a part of something. The night before, during a routine police raid on the Stonewall Inn, something far from routine had happened: the bar’s patrons—and mainly its trans women and drag queens of color—fought the police, refusing to be cleared out or taken to the station. It was electric, in part because it seemed spontaneous and so unlike previous, tamer acts of gay resistance in the city, which had been organized by homophile organizations such as the Mattachine Society. Passersby were drawn to and then into the action that night as affinities were forged in the street.

Gay liberationists didn’t want what straight, middle-class white America had. They wanted a new world in which conventional structures of domination were abolished.

The next night, a diverse group of sexual outsiders—what we would now gloss as LGBTQ—gathered in front of the bar, ready to stand their ground. But the police also returned in greater numbers, eventually joined by units from the NYPD’s notorious Tactical Patrol Force in riot gear. Many officers came eager to swing billy clubs and reassert the force’s dominance. They confronted an emboldened crowd of up to 2,000 people that included a drag chorus line, kiss-ins, and chants of “Gay Power!” The crowd erupted when officers attempted to clear the area.

Some of the most familiar photos of Stonewall were taken on this second night, including those of an exuberant group of young black, Latinx, and white men and gender-queer folks posed in front of the bar’s boarded-up window. Behind them are chalked slogans of collective resistance: “They Invaded Our Rights,” “Legalize Gay Bars and Lick the Problem,” “Gay Prohibition Corupt$ Cop$ Feed$ Mafia.”

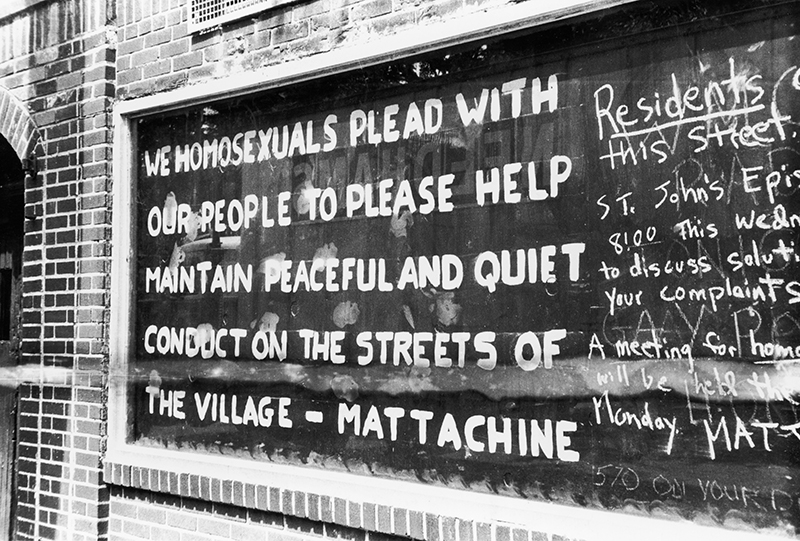

By the next day, Sunday, June 29, a new message with a very different, conciliatory tone had appeared on the boards covering the broken window. Painted in large, uniform block letters, all capitalized, and filling much of the space, it read:

WE HOMOSEXUALS PLEAD WITH OUR PEOPLE TO PLEASE MAINTAIN PEACEFUL AND QUIET CONDUCT ON THE STREETS OF THE VILLAGE—MATTACHINE

Beside it, filling the rest of the space, was a notice for two public meetings to be hosted by the city’s chapter of the Mattachine Society. Both meetings would be at St. John’s Episcopal church, the first for area residents to “discuss solutions” to their “complaints” about the weekend’s events, and the second “for homosexuals.” Traces of the board’s chalked slogans from earlier in the weekend remained faintly visible, however, including part of the phrase, “Gay Power.”

Since the early 1950s, Mattachine had been working toward the decriminalization of homosexuality, encouraging gays to see themselves as like an ethnicity, with the aim of being accepted as equals in mainstream society. Although the organization had radical origins in the American communist movement, by the time of Stonewall it firmly aspired to be in the political and social center. Mattachine had always been exclusively cisgender male and predominantly white; by the time of Stonewall it was often working in concert and sharing meetings with women of allied homophile organizations with similar compositions, notably the Daughters of Bilitis.

Despite Mattachine leaders’ exhortation to “our people,” the uprising continued for three more days. While far from being the first instance of collective resistance to the oppression of gay, lesbian, gender nonconforming, and queer people in the United States, events at Stonewall were transformative not only in giving energy to organizing but in fueling debates among LGBTQ people over what constituted freedom and how best to achieve it.

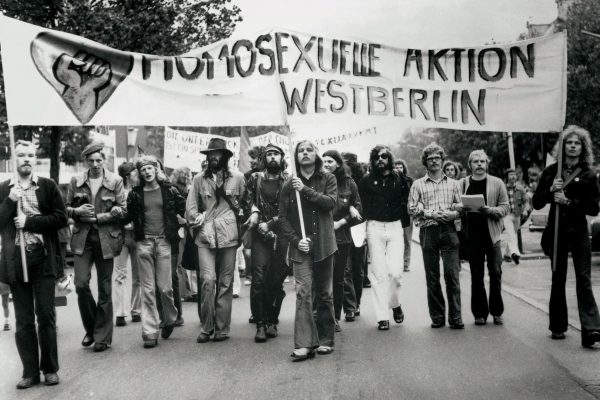

The first pride march was held in New York City on June 28, 1970, to mark the one-year anniversary of the uprising. Described by Kiyoshi Kuromia at the time as “the first birthday of our movement,” the parade also marked a key moment in the history-making project that would enshrine Stonewall and Gay Liberation as points of origin for the LGBTQ political movement and eventually harness both to a single-issue liberal rights agenda.

Buttigieg’s Stonewall is not that of the fed-up liberationists in the bar and on Christopher Street, but rather of Mattachine leaders’ sanguine next-day appeal to ‘rioters’ to be peaceful and decorous.

This was not at all what Kuromia, a cofounder of the Philadelphia Gay Liberation Front, was talking about as “our movement.” He hailed the 20,000 marchers in New York’s first gay pride parade, including himself, as having come together to “topple your sexist, racist, hateful society,” adding, “We came to challenge the incredible hypocrisy of your serial monogamy, your oppressive sexual role-playing, your nuclear family, your Protestant ethic, apple pie and Mother.” This was Gay Liberation writ large, a politics generated in the immediate aftermath of Stonewall with the goal of upending and remaking society. Informed by Marxist anticolonial movements and the global revolutions of 1968, gay liberationists didn’t want what straight, middle-class white America had, they wanted a new world, one in which conventional structures of domination and inclusion/exclusion were abolished.

This bears little resemblance to the incrementalist LGBTQ rights movement we have today, characterized by the signal goals of open military service and marriage equality. The messy dynamism, diversity, and radical potential of Stonewall has been assimilated as an easy shorthand for the success of U.S. liberalism, with its inevitable (if hard-won) progress and inclusion. Surely it is this vision of Stonewall—rather than a drag queen throwing a shot glass through a mirror, the act many remember as starting the uprising—that Barack Obama meant to invoke in his second inaugural address when he said, “We, the people, declare today that the most evident of truths—that all of us are created equal—is the star that guides us still; just as it guided our forebears through Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall.”

Just in time for Stonewall’s fiftieth anniversary, the recasting of it as the origin of a centrist rights movement has been incarnated in the person of Democratic presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg, who has offered himself—and been widely embraced—as the embodiment of Stonewall’s successes and political future. As a moderate Democrat who embraces a particular species of Middle American wholesomeness, the idea of him embodying Stonewall is nearly incomprehensible—unless one begins from the position that Buttigieg’s Stonewall is not that of the fed-up liberationists in the bar and on Christopher Street, but rather of Mattachine leaders’ sanguine next-day appeal to “rioters” to be peaceful and decorous.

Ironically, a key qualification for Buttigieg’s embodiment of this particular variety of gay mainstreaming identity politics is his reluctance to identify with it. Four years ago, Buttigieg was “not eager to become a poster child for LGBT issues,” he explains in his recent political memoir, Shortest Way Home. “I had strongly supported these causes from the beginning, but did not want to be defined by them.” Indeed, in 2016 Buttigieg was an early adopter of the argument that Democratic “identity politics,” in conjunction with the neglect of Rust Belt voters, had given the election to Trump. Buttigieg’s first national campaign started in January 2017, when he ran for chair of the Democratic National Committee on a platform that combined that two-pronged critique with appeals to his own status as a young, gay, military veteran from the Midwest. He relied on the malleability of “identity politics” to absorb the obvious contradictions, while mobilizing the term’s knee-jerk trigger potential.

At its core, ‘belonging’ for Buttigieg means integration and the freedom of access: ‘above all, I am running as an American.’

Shortly before entering the race for DNC chair, Buttigeig published an opinion piece outlining his vision for the party’s future. In “A Letter from Flyover Country,” he located himself geographically, culturally, and generationally as speaking from outside the Washington establishment. This was reinforced by a series of illustrating images in the following order: the mayor speaking to other white men in suits against the background of his small city’s skyline; an aerial shot of downtown South Bend, Indiana; the mayor talking to a white man in a hardhat in front of a “Welcome to South Bend” sign; Buttigieg in combat uniform smiling into the camera as he sits on an outcropping of rock in Afghanistan, holding an M4 Carbine in a right-handed grip (despite being left handed) so as to display his name and the American flag decorating his right bicep; and finally, the mayor standing beside his boyfriend, surrounded by a multiracial group of men, women, boys, and girls behind a red-white-and-blue banner reading, “Happy Fourth of July from the City of South Bend.” In the written part of the narrative, Buttigieg adds to the list of social locations, or identities, that distinguish him from establishment Democrats: he has seen Afghanistan as a uniformed serviceperson, not “on the news”; and for him, marriage equality “isn’t a political rallying cry” but defines the shape of “my future family.”

Broadly, Buttigieg urged the national Democratic party to return to fundamental values: “Our values are American values.” This meant “organiz[ing] our politics around the lived experience of real people,” he argued, those “whose lives play out not in the political sphere but in the everyday, affected deeply and immediately by how well we honor our values with good policy.” In the political sphere, he said the party had pursued a fractured and fracturing “salad bar” strategy of offering different things for different groups to its detrement. “The various identity groups who have been part of our coalition should be there because we have spoken to their values and their everyday lives — not because we contacted them, one group at a time and just in time for the next election.”

Buttigieg staged his argument through an oppositional pairing of the Democrats’ focus on “identity” as opposed to the values of “real people.” There is left in this binary formation a discomfiting space, however, in which the subjects of campaign strategies can be read simply as the subjects themselves: groups with “identity politics” as opposed to “real people” with real, “everyday” problems. Buttigieg relied on this slippage to appeal to politics of identity while simultaneously rejecting them. Speaking in Washington, D.C., for instance, he quipped, “Thanksgiving morning, by the way, I spent in a deer blind with my boyfriend’s father, so how’s that for a 2017 experience?”

By pointing out the many ways his own experience deviates from common assumptions about gay men’s lives, Buttigieg further reinforced his “just folks” argument of fundamental American sameness through shared aspirations. His rejection of what he sees as gay stereotypes seems aimed at ingratiating him with queer critiques of the cosmopolitan urban bias of mainstream LGBTQ politics and cultural representation, even as his identification as “just folks” distances him from queerness in general. More resounding were the echoes of the anti–coastal city, “real America” of Fox News and the Republican Party.

Played for laughs, usually, or offered as irreverent assides, Buttigieg made false equivalents—we all have identity—to promote his change agenda while simultaneously marking himself as a diversity candidate. Speaking at a forum hosted by George Washington University in Washington, D.C., the belly of the establishment beast, Buttigieg opened his remarks with an assurance that calling for greater attention to white working people did not mean rejecting the party’s defining commitments to racial and social justice, before moving again to his “salad bar” analogy. “We think the only way to speak to somebody is one group at a time, that’s never computed for me,” Buttigieg explained, and then he paused, smiled, and turned to one of his rivals for the chair position, Jehmu Greene, a black, first-generation daughter of Liberian immigrants who grew up in Texas. “Jehmu was talking about intersectionality. I’m a walking intersectionality. I’m a left-handed, Maltese-American, Episcopalian, gay, war veteran, alright? I don’t know exactly which caucus I should go to first.”

There is no room in Buttigieg’s political vision for those standing outside the wall to look back and say, ‘Man, those people are fucked. Let’s get out of here, before what happened to them happens to us.’

Buttigieg’s campaign for DNC chair was unsuccessful, but the tactic proved winning. He now brings a much more sophisticated version of this anti–identity politics identity politics to the Democratic primary race. The message clearly resonates, propelling the long-shot candidate to a three-way tie with Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders for second place in a recent poll.

In his keynote at a Human Rights Campaign fundraiser in mid-May, Buttigieg gave a version of his stump speech tweaked for his LGBTQ audience. In it, he more directly addressed “so-called identity politics” and its contemporary political uses. Rather than dwell on our differences from one another or comparative oppressions and suffering, the candidate urged his audience and his party to see in “identity the beginning of a new form of American solidarity by recognizing that the one thing we do have in common may be the challenge of belonging.” The notion of “belonging” does a lot of work for Buttigieg, not the least of which is providing a way to talk about the structural inequalities that exclude so many from the American promise along lines of race, class, gender, legal status, ability, and sexuality. The candidate is also careful to note the intersecting quality of these categories in the lived experiences of exclusion and disfranchisement. But at its core, “belonging” for Buttigieg means integration and the freedom of access; “above all,” he told the HRC, “I am running as an American.”

In this view, the table to which all should be able to pull up—the liberal promise of a place card for everyone—is one of unquestioned bounty and desirability. Systemic change need only come in making more places and easing more people’s ways into them. A big part of this for Buttigieg is changing the mindsets of the excluded who think of themselves as so different because they feel rejected: “what every gay person has in common with every excluded person of any kind is knowing what it’s like to see a wall between you and the rest of the world and wonder what it’s like on the other side.”

There is no room in Buttigieg’s political vision for those standing outside the wall to look back and say, “Man, those people are fucked. Let’s get out of here, before what happened to them happens to us.” There is no room for those standing outside to throw a rope over, or to dismantle the wall in order to build something different with those who have lived inside of it. There’s no room in his Stonewall Inn for most of what happened at Stonewall, in other words.

As for many LGBT people with sincere commitments to mainstream belonging, family and marriage are key to Buttigieg’s public identity, at the center of which stands his husband, Chasten Buttigieg. In May, the couple was depicted on the cover of TIME, wearing complementary dress shirts and navy khakis standing shoulder-to-shoulder in front of their remodeled Victorian. The phrase “First Family” was emblazoned across them in large print. The cover solidified Chasten as a highly visible and enormously popular feature of the campaign, traveling with the candidate, making solo appearances on his behalf, and maintaining a lively social media presence. Chasten comes across as the earnest, endearingly goofy theater gay that the United States fell in love with on Glee.

Of all of the marriages on either side of the 2020 presidential race (including the Pences’), the Buttigiegs most obviously adhere to the roles and customs of a traditional Christian union.

Politico recently headlined a story about the Chasten phenomenon: “Chasten Buttigieg is Winning the 2020 Spouse Primary.” The author, Joanna Weiss, argues that, more than anything else, what has made him so popular and given his husband such a boost is that Chasten is the most traditional spouse in the mix. For instance, when they married a year ago, he took his husband’s last name; he’s on leave from his job—as a drama teacher—so he can devote himself full time to supporting his husband; he speaks openly and sincerely of how much he loves and admires Pete as a man and as an elected official; he honors Pete’s Christian faith. Many Americans have warmed to Pete Buttigieg because of his husband’s warmth and likability, and because, of all of the marriages on either side of the 2020 presidential race (including the Pences’), the Buttigiegs most obviously adhere to the roles and customs of a traditional Christian union. Writing for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Greta LaFleur put it best when she described the couple as an example of “Heterosexuality Without Women.”

This focus on family and domesticity mirrors the candidate’s own version of LGBT progress. At the end of his memoir, Buttigieg indulges the nostalgia for the postwar affluence and cultural fantasies of the 1950s that have long fueled not only the politics of Make America Great (Again), but dreams shared on the left of a largescale return to domestic industrial manufacturing. He strolls imaginatively through the streets of South Bend in the flush times, before Studebaker’s demise, noting how lovely it seems, before acknowledging how ugly it actually was for women, people of color, and LGBT people:

I probably would not find any sign of gay life, but if I did, it would be nowhere near the Episcopal Cathedral of Saint James, completed in 1894, where I would one day get married to Chasten. Instead it would be in some sketchy bar or alley where men fearful of exposure would exchange coded and furtive glances, totally unable to imagine that in a future generation they might have known the incomparable joys of authentic love and marriage.

Remember that qualification, “authentic” love. We’ll return to it shortly. But, first, back to the “sketchy bar.”

The Stonewall Inn was a popular spot in 1969. It was large, had a dance floor, go-go boys, and boasted a loose door policy if one could pay the cover charge. It was popular with a racially diverse crowd of gays, lesbians, gender nonconforming people, drag queens, hustlers, street kids, college students, and out-of-town visitors. Many of the bar’s patrons were not welcomed at other clubs and cocktail lounges in the West Village that catered to wealthier, more discretely gay crowds. Like most gay bars in New York at the time, the Stonewall was run by organized crime, which exploited a captured market in exchange for paying off the police. The bar was also known for watered-down drinks, filthy bathrooms, a level of general seediness, and regular police raids.

Many Stonewall participants were activists in women’s liberation and the anti-war, anti-colonial, and anti-capitalist movements; many were also part of the student left and the counterculture.

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were both Stonewall regulars before they were leaders in the gay and transgender liberation movements. Today, they are arguably the most recognizable historical figures of the Stonewall uprising. Neither had planned to be at the bar the night it was raided. It was Johnson’s twenty-fifth birthday, and she was throwing a party. Rivera had been invited, but was exhausted from a string of night shifts and decided to stay in. She planned to light prayer candles for Judy Garland, whose funeral earlier that day had drawn 20,000 mourners in vigil along East Eighty-first Street and Madison Avenue. (Garland’s funeral was not the cause of the Stonewall uprising as some would later claim, but it was certainly woven through individual experiences of the event.) Rivera was talked into going out by a friend; they met downtown at the Stonewall.

It is tempting to think of the Stonewall “riots” as a spontaneous eruption of enraged resistance by marginalized people who just couldn’t take it anymore. But, like the black and Latinx urban uprisings of 1965, ’67, and ’68 to which many likened Stonewall, to do so is to isolate the people and their acts from politics, to ignore that their actions were not unreasonable responses to the conditions of state violence, oppression, and limited options. This was what Martin Luther King, Jr., meant in 1967 when he explained that “riots do not develop out of thin air”; rather, they are “the language of the unheard.” In the case of Stonewall, it is also to isolate LGBTQ people from the broader political tumult of their time, from the social movements and diverse liberationist aims of the late 1960s. Many participants were activists in women’s liberation and the anti-war, anti-colonial, and anti-capitalist movements; many were also part of the student left and the counterculture. Elliot Tiber was at the bar when it was raided and joined in “rioting,” for instance. As a closeted gay man from out of town, he felt liberated by the experience, which he took home with him to Bethel, New York. A few weeks later, with the entire festival in peril, he secured a permit and new location on a neighbor’s farm for the organizers of Woodstock.

As well, many who rose up on Christopher Street were members of homophile organizations, which had in recent years turned increasingly to picketing and other forms of direct action. In 1966 the president of New York Mattachine, Dick Leitsch, had staged a gay “sip-in” at a downtown bar, inspired by the sit-ins of the civil rights movement. He notified the press, gathered other white men in suit jackets and ties, and went to get a drink. After Leitsch was served, he announced that he and his companions were all gay, at which point the bartender placed his hand over the fresh cocktail and refused to serve them. This moment was captured by a photographer for the New York Times. Like the “sip-in,” homophile picket lines had strict dress codes requiring men to wear ties and jackets, while the women had to wear dresses or skirts. Many years later, Rivera quipped of those early actions: “Lesbians who’d never even worn dresses were wearing dresses and high heals to show the world they were normal. Normal?” Rivera wasn’t the only one to comment on the particularly upsetting sight of butches forced into dresses in order to claim their rights as lesbians.

Mirroring black civil rights strategies of respectability from the early 1960s, homophile policing of self-presentation and decorum seemed to many outdated and conservative, more “Silent Majority” than resistant minority. These strategies animated Leitsch’s call for calm and “quiet conduct” during Stonewall, and persisted in conflicts among activists in the organizing fervor that followed.

Less than a month after the uprising, participants and those inspired by them founded the Gay Liberation Front. In a July 31, 1969, interview with the wide-circulation alternative paper Rat, the new group explained what they were about. To the question, “What makes you revolutionaries?” they responded:

We formed after the recent pig bust of the Stonewall. . . . We, like everyone else, are treated like commodities. We’re told what to feel, what to think, what to be . . . all for the needs of a money-making machine that has successfully packaged us all into antagonistic groups, keeping us divided by racism, sex, and other fears. We identify ourselves with all of the oppressed: the Vietnamese struggle, the third world, the blacks, the workers . . . all those oppressed by this rotten, dirty, vile, fucked-up capitalist conspiracy.

“Can you pinpoint the oppression as it specifically relates to homosexuals?” the interviewer queried.

The socialization process of the society is nothing but a phony morality impressed upon us by church, media, psychiatry, and education which tells us that if we’re not heterosexual married producers and pacified workers and soldiers that we are sick degenerate outcasts. We expose the institution of marriage as one of the most insidious and basic sustainers of the system. The family is the microcosm of oppression.

Old conflicts as well as new ones soon emerged among activists, and Gay Liberation groups quickly divided. On one side were those committed to revolutionary change and radical alliances based in recognition that everyone is subject to different kinds of interlocking oppressions—what we would now call intersectionality. On the other side were those who believed that the sole focus of organizing should be efforts toward the equality and integration of gays and lesbians. This division was formalized in December 1969 with the founding of an alternative to the GLF: the Gay Activist Alliance.

The choice by predominantly white, cisgender gays and lesbians to exile the queerest elements of the LGBTQ community in the name of mainstreaming created what we now call gay rights.

For others, the stated radical intersectionality and universalism of the Gay Liberation Front didn’t match the organization’s realities. In response, many activists started organizations that focused on the needs of their own communities. Rivera and Johnson, for example, founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970 to address the housing and security needs of poor, gender nonconforming people who moved in and out of sex work and homelessness. That year also saw the creation of Third World Gay Liberation and Radicalesbians. The representative face and concerns of Gay Liberation were narrowing, compelling Rivera to remind her fellow activists in 1972 that the “first stone was cast by a transvestite half sister” at Stonewall and urging them to “remember that transvestites and gay street people are always on the front lines and are ready to lay down their lives for the movement.” By 1973, when she was booed while trying to speak from the stage at New York’s Pride celebrations, the possibilities for radical alliances seemed all but over. “We died in 1973, the fourth anniversary of Stonewall,” Rivera later explained.

This choice by predominantly white, cisgender gays and lesbians to exile the queerest elements of the LGBTQ community in the name of mainstreaming created what we now call gay rights. It is a position still largely ascendent in national advocacy organizations including the Human Rights Campaign, which argue that their incrementalist approach to centrist issues such as gay marriage is simply what is necessary to move the needle. To members of the community who benefit little if at all from these kinds of “progress”—for example, trans people who can still be legally fired from their jobs—the message is clear: we’ll get to your special issue, wait your turn. And it is arguably in this same spirit that Buttigieg writes in his memoir of his ability to live in the straight world in ways that are closed to many LGBTQ people:

Perhaps it is the fear of any queer person preparing to come out that he or she will be marked as a kind of other, isolated from the straight world by virtue of being different . . . [but the real consequence] is that I have felt more common ground than ever with the personal lives of other, mostly straight people.

In One-Dimensional Queer (2018), sociologist Roderick Ferguson addresses the profound costs exacted by “mainstreaming queerness,” as has been done in the official memory of Stonewall enshrined in monuments, histories, and consumer capitalism (hello, Pride corporate sponsors). The cost of this literal and figurative whitewashing are disproportionately born by the very same people of color, the poor, the sexually dissident, and the gender nonconforming who were central to the uprising. By making queerness “conform to civic ideals of respectability, national belonging, and support for the free market,” he argues, “gay rights and gay capital helped renew racial, ethnic, class, gender, and sexual exclusions.” Ferguson notes the centrality of history-making to this process: “divorcing queer liberation from political struggles around race, poverty, capitalism, and colonization helped conceal the historical and political complexity of queer liberation itself.”

The common urge to belonging that Buttigieg offers as the antidote to identity is always conditional because it demands mainstream recognizability. It is a cruel and high bar to belonging, and it is a devastatingly low estimation of the horizon of human intimacy.

Pete Buttigieg is careful to explain that he did not meet Chasten in some sketchy gay bar, but through the dating app Hinge. Their first in-person date did start at a popular Irish pub in South Bend over pints and scotch eggs. It ended at the local minor league ballpark, home to the South Bend Cubs, where the men shared their first kiss under the post-game fireworks. “Other than the same-sex aspect,” Buttigieg writes, “our first date was something our parents could have recognized as typical, almost vintage.”

And therein lies the rub. The common urge to belonging that Buttigieg offers as the antidote to identity, as the glue to bind a diverse and far-flung people, is always conditional—it’s always a butch in a dress—because it demands mainstream recognizability. Rather than resist the notion of conditional rights, Buttigieg leans into and even celebrates it, and encourages others to do so as well. In a near perfect inversion of the revolutionary aims and relational politics inspired by Stonewall, Buttigieg locates the very possibility of solidarity in shared conditionality.

That is how one becomes “real people.” That is the measure of “authentic love.” It is a cruel and high bar to belonging, and it is a devastatingly low estimation of the horizon of human intimacy.

When I saw that Out had selected Pete Buttigieg for one of its three Pride issue covers in the theme of Stonewall: Then, Now, Next—alongside the late Sylvia Rivera and trans actor Mj Rodriguez—my thoughts turned unseasonably to Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. In Dickens’s classic story of a never-married, miserly old crank successfully assimilated to “shared” family values, Ebenezer Scrooge confronts his last trial with a horror amplified by his sense that it is for his own good: “‘Ghost of the Future,’ he exclaimed, ‘I fear you more than any spectre I have seen.’”

But the ghosts of Stonewall’s unruly past and radical queer possibilities have not left us; they have not been totally silenced in the progress narratives of recognizability. As in “Sappho’s Reply,” the 1971 poem by Radicalesbian activist and writer Rita Mae Brown, they cry: “Tremble to the cadence of my legacy: An army of lovers shall not fail.”