In the Matter of Nat Turner: A Speculative History

Christopher Tomlins

Princeton University Press, $29.95 (cloth)

Philosopher and literary critic Walter Benjamin encapsulated the task of the historian in two quotations. The first borrows from the language of photography: “The future alone possesses developers strong enough to reveal the image in all its details.” The second is taken from Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal: “Read what was never written.” It is with this motto that Christopher Tomlins closes his complex and compelling restitution of Nat Turner, prophetic leader of the 1831 slave insurrection in Southampton County, Virginia.

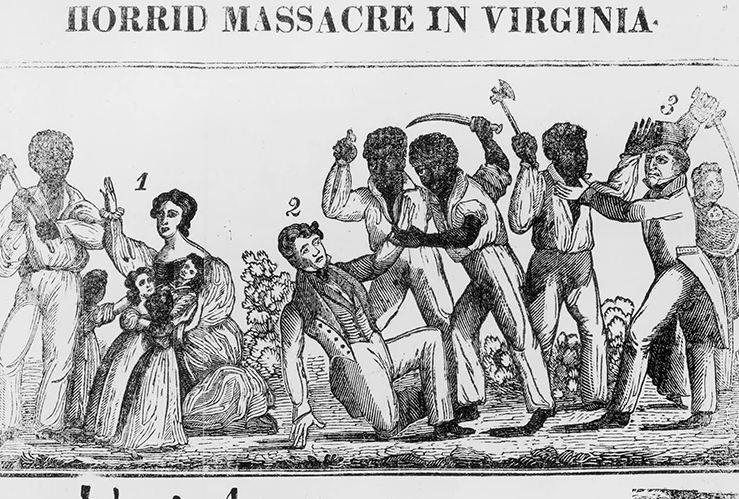

A preacher (or “exhorter”) who forged his own apocalyptic Christian vision in seeming isolation from his community, Turner led several dozen enslaved companions into a brief and bloody campaign of liberation across the plantations on which they were forced to labor. Never before in the United States had so many whites died in a slave revolt. Decried as a sanguinary fanatic by defenders of the “peculiar institution,” Turner became a byword of uncompromising resistance, inspiring John Brown’s own efforts at insurrection and living on in the pantheon of radical Black abolitionism. Tomlins’s book builds on a decades-long engagement with Turner’s effort to unmake slavery through a kind of “divine violence.” It draws on a rich arsenal of reading methods to try to recover the unsettling uniqueness of his prophetic vision and its aftereffects on the politics and economy of the slaveholding South—all the while striving to bring that history into dialogue with our own tumultuous present.

The collective resistance and violence of the dominated, and even more so the enslaved, has long posed formidable challenges to historical inquiry at the level of method as much as morality. When oppression and exploitation include a monopoly over the means of legitimate communication—when free speech or even literacy are confiscated—what could the historical record be but power’s gilded mirror? Writing history against the grain, against the self-image of the victors’, has meant inventing methods of reading, deciphering, and recomposing the archives of domination to let other voices ring out.

In different ways, the voices of the resistant and of the defeated appear in the official archives largely as objects of control and punishment. Yet however hard the thumb of the powerful presses down on the scales of history, redress is never obliterated. So much is attested to by such classic works of oppositional history as Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms (1976), which reconstructs the cosmology of a sixteenth-century Friulian miller through the records of his Inquisition trial; Ranajit Guha’s portrayal of rebel consciousness reconstructed from the records of imperial administrators in Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (1983); Nathan Wachtel’s excavation of the traces of Inca culture after the cataclysm of the conquista in The Vision of the Vanquished (1977); and, more recently, Saidiya Hartman’s eloquent reimagining of the cultural revolutions carried out by young Black women in the early twentieth century in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019).

That Nat Turner should command the interest of Tomlins—a legal theorist and historian of the Early Republic—is no surprise. Especially not if we recall that the bulk of our information on Turner is drawn from The Confessions of Nat Turner, a text composed by Thomas R. Gray, lawyer for several of the Southampton Rebellion defendants, as well as a literary entrepreneur and slaveholder. For Tomlins, Gray’s was just the first attempt by a white man to turn the rebel slave, his consciousness and his narrative, into the “textual property of another.”

Attempts to produce a definitive textual portrayal of Turner certainly did not end with Gray, and have often proven intensely controversial. In novelist William Styron’s 1967 Confessions of Nat Turner, for example, the dignity of Turner’s theology is dismissed, while his motives are reduced, in Vincent Harding’s trenchant formulation, to “indecisive, sexually symbolized impotence, the killing without conviction which marks Styron’s black-white man indelibly as a twentieth-century anti-hero.” The novel provoked a prolonged series of rebuttals, including John Henrik Clarke’s edited volume William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond (1968). In the prologue to In the Matter of Nat Turner, which reviews these, Tomlins masterfully excavates how Styron’s novel substitutes the hostile, enigmatic Turner its author saw in Grey’s Confessions—“a ruthless and perhaps psychotic fanatic”—with what Tomlins bitingly terms “a different knowable Negro,” one of whom Styron “could take complete possession.” Tomlins also tracks the tendentious ways in which Styron mobilized the authority of Georg Lukács’s The Historical Novel (1955) to argue that his work fulfilled the Hungarian Marxist’s criteria of commanding the historiography of the period while unburdening himself of “the dead baggage of facts.”

Significantly, this claim to authorial freedom, of a right of disposal over Turner’s history and psychology, dismissed the figure of the insurgent leader treasured in Black oral history. Here Tomlins’s retelling of Styron’s research visit to Southampton County, as reported in his 1965 Harper’s article “This Quiet Dust,” is particularly damning. Styron reported that his conversations with locals suggested that “it was as if Nat Turner had never existed,” thus making Turner a screen on which Styron could project at will. But as Tomlins wryly observes:

The story is entirely bizarre: Accompanied by his father and his wife, Styron tours backcountry Southampton in the county sheriff’s squad car, ‘with its huge star emblazoned on the doors . . . its riot gun protectively nuzzling the backs of our necks over the edge of the near seat,’ in search of passersby whom they can stop and quiz on what they know about the Turner Rebellion.

While Styron’s forgeries of memory and meaning are deftly exposed in Tomlins’s dossier, he does grant the validity of Styron’s ambition that the figure of Turner be made the site of a “meditation on history.” But such a meditation—on the past, on its writing, on how to enliven and be enlivened in it—can proceed only if we first jettison a whole set of modernist and historicist prejudices, the very ones that Benjamin’s critique of the ideology of progress and reflections on the conditions for history’s legibility made possible.

What both modernism and historicism cannot countenance, and which Styron too recoiled from, is Turner’s religious “fanaticism”—the prophetic, apocalyptic rationale for his instigation of the rebellion. As a consequence, Turner’s visionary biblical language has by and large been interpreted as but a screen for his desire for liberation, an urge comfortably transposable into secular terms. In this accounting, the Spirit who appeared to Turner on May 12, 1828—telling him that Christ had lain down the yoke and it was time to fight the Serpent—was but a hypostasis of Black rebel consciousness, the Serpent slavery.

But Tomlins is adamant that to write an intellectual history of Turner demands taking the measure of his “fanaticism” and trying to recover what justice meant to him—as an exhorter, a prophet, and a theological thinker. This necessitates not only refusing to treat religious form as the mere ornament for social content, but also endeavoring to grasp the singularity—the excess—of the figure of Turner vis-à-vis a secular history. Tomlins here makes compelling use of philosopher Alain Badiou’s understanding that all events possess an “excess” never fully enclosed by their recounting. The truly new or revolutionary—such as a slave uprising—is, from the vantage of the world into which it irrupts, impossible, unthinkable, beyond accounting.

Yet Tomlins’s wager is that Turner is knowable, if not possessable, if we attend to the traces that he and his rebellion left behind. As with Ginzburg’s recovery of the cosmology of the miller Menocchio, Tomlins’s salvaging of Turner and his thought from the traducements and condescension of posterity is, at least in the first place, an eminently forensic affair. The book’s first chapter is a bravura textual anatomy of Gray’s pamphlet—from the statement of copyright to the certification of the document by six Southampton Court justices, from the trial report to the lists of the massacred and the tried. The painstaking review of the composition of the text is intended not just to detail how Gray could take possession of (and seek to profit from) the words and acts of Turner, but aims at weighing up the evidentiary power of the document.

Against dismissals of The Confessions of Nat Turner as Gray’s confection, Tomlins argues, meticulously grounding himself in textual forensics, for it being a faithful record of a singular theological-political imagination. This imagination, as the key chapter “Reading Luke in Southampton County” details with insight and erudition, can be traced to Turner’s relation to the Gospels (and not the Old Testament, as so many commentators have supposed) as well as to evangelical networks that allow one to connect Turner to postmillennialist Methodism (rather than a premillennialist Baptist tradition) and back further to evangelical preacher Jonathan Edwards and the Moravian Church. These final two, for Tomlins, are critical to understanding both the place of blood imagery in Turner and the sources for some of his most distinctive formulations, not least among them the call that he should arise and prepare himself “and slay my enemies with their own weapons” (for Turner, the master’s tools could indeed dismantle the master’s house). This formula received its theological crystallization in Edwards’s contention that, just as David delivered the Hebrews, “Christ slew the spiritual Goliath with his own weapon, the cross, and so delivered his people.” Tomlins presents this work of theological archaeology as indispensable to recovering the singularity of Turner’s self-understanding.

More problematic is Tomlins’s contention that it is in the doctrines of the transatlantic evangelical revival of the 1730s that “all the essential elements of Turner’s messianic comprehension of his own purpose” can be located. Does Turner’s apparent repudiation of the spiritual and magical legacies of Africa (the “conjuring and such like tricks” that he claims to have always spoken of with “contempt”) mean that we can isolate him from his “society” (of the enslaved) and its culture? And if we treat him as wholly apart from traditions of Black spirituality (and of the political defiance that might have arisen from them), does this oblige us to see him as having drawn all his intellectual and spiritual sustenance from a Euro-American spring? Of the Denmark Vesey conspiracy, an 1822 quashed slave uprising in South Carolina, Sterling Stuckey contends that “the most acculturated slaves, like slaves generally, appropriated values from the larger environment and relied on African values that pointed the way to creative solutions to a variety of problems, cultural and political.” Can we not suppose the same of Turner and his rebellion? And what of Theophus Smith’s provocative claim that not just evangelical exhortation but also “magical shamanism” was present in Turner, a modality that “features ostensibly the repression of conjure but (precisely thereby) the return of conjurational impulses via biblical symbolism and Christian theological discourse”? Or that, as Walter C. Rucker suggests, the visions, omens, and “knowledge of the elements” to which Turner claimed access had roots in non-Christian African culture?

Here, Tomlins’s methodological strictures—which combine an ear for the event with a forensic, evidentiary gaze—seem to force him to bracket out (though not necessarily to dismiss) that which could never have been written because it took place in an entirely non-textual and perhaps even unconscious experience. Cedric Robinson has suggested that “Nat signaled the appearance of a new historical, psychological, and cultural phenomenon, a personality forged from a cultural fusion coincidental to the enslavement of Africans in the New World.” In remaining, if brilliantly, within the bounds of a “textual conspiracy,” Tomlins may have circumvented this fusion.

Tomlins’s reconstruction of Turner’s singular vision is followed by a philosophical-anthropological investigation. Here Tomlins draws on two towering figures of European thought who were contemporaries of Turner, Danish thinker Søren Kierkegaard (eighteen at the time of the events in Southampton County) and German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (who died three days after Turner’s hanging). Unlike in the book’s first section, no evidentiary claim is made here. Instead Tomlins draws on two salient moments in these thinkers’ figurations of subjectivity: Kierkegaard’s “knight of faith,” adapted from the biblical story of Abraham’s “absurd” decision to sacrifice his son Isaac; and Hegel’s “master–slave” dialectic as a drama of recognition and deferred violence.

Behind Turner’s stark imperative to “rise and kill all the white people,” Tomlins, with Kierkegaard, allows us to see the rebel leader’s foremost challenge, that of persuading to action his enslaved companions, whose reasons for following him differed emphatically from the faith that led him to pick up the sword. As Tomlins observes, Turner’s “comrades are not knights of faith,” yet Turner “must still persuade them to come with him on the journey he began in faith.”

To persuade them he must enter the creaturely world they inhabit, and he must address them on its terms: he must take men, rather than God, as his criterion. He must discover a politics that will allow them, collectively, to act—beyond ethics, beyond legality.

The disjunction, but also the insurgent spark, between faith and politics runs between the “leader” and his “followers.” The “new universal” that Turner invents is not an act of religious exhortation. The rebels need not have been persuaded of the millennium (neither the Confessions nor their own trial records suggest as much) and their own motives seem disjoined from Turner’s visions. Will Francis, whose axe will carry out much of the “work of death,” as Turner calls it, is reported in the Confessions to advance this explanation for his rallying to Nat: “his life was worth no more than others and his liberty as dear to him.”

Rather than flinching from the rebellion’s character as a methodical massacre, Tomlins tries to confront it head-on, chronicling it in forensic detail while meditating on the sense in which the killing was constitutive of liberation, and what it might have meant for an enslaved person to describe it as “work.” In the process, he shows how the Southampton rebellion upended Hegel’s view of labor as that which allowed the dominated to attain self- consciousness after they had avoided death by their own submission. Turner’s dialectic is not Hegel’s. As we read in the Confessions, “I sometimes got in sight in time to see the work of death completed, viewed the mangled bodies as they lay, in silent satisfaction.” Rather than treating the violence as a sign of derangement, it is charged with significance. As Tomlins concludes, interleaving his own words with those of the German philosopher:

Turner’s ‘work of death’ was death-work that he and his comrades performed in the service of their self-transformation, through a cancellation and destruction of the other, from bondsmen subordinated by fear, ‘consciousness repressed within itself,’ into willful actors possessed, however fleetingly, of ‘real and true independence.’

The book’s third and final part details the rebellion’s enactment of “countersovereignty”—of violence in the service of root-and-branch transformation—and how it comes to be inscribed in the political and legal record principally as something to be foreclosed. Through an exhaustive review of the legislative debates that took place in Virginia on either side of the Southampton Rebellion (in 1829–30 and 1832), as well as of the extensive dispute over slave labor at the U.S. Navy docks in Norfolk, Tomlins takes us through the ways in which the specter of slave rebellion affected an extremely precarious polity, through budgetary and ideological struggles that largely pitted “brittle eastern slaveholders and resentful western yeomen, occupied in incessant squabbling over the terms of [Virginia’s] modernization.” The “wild risk of change” embodied by Turner’s insurgent political theology and its shocking effects, as well as its contribution to rifts among white interests, came to be neutralized for a time not by schemes of emancipation or removal (as some legislators suggested) but by a change in the very ideology of slavery, from its justification in a paternalist civilizational conceit to a full embrace of the logic of the commodity.

This is evidenced especially in the writings of the wan villain of Tomlins’s book, Thomas Roderick Dew, professor and then president of William and Mary College, who endorsed slavery as “not a liability but the source of Virginia’s comparative advantage for as long as it remained a predominantly agricultural state.” Here Tomlins brings home the “disjunctive dialectic” between Turner’s faith, misrecognized as fanaticism yet capable of persuading his comrades to wager their lives for freedom, and white Virginia’s new faith, namely political economy, the language of the bottom line. This was the lexicon in which the governor of Virginia, John Floyd, penned a letter in September 1831 wondering, “What the effect of this insurrection is to be upon the commercial credit of the state, upon individual credit, is a point of view not at all pleasant, to say nothing upon interest upon loans for the state itself, should she ever wish to borrow.”

Tomlins endorses Benjamin’s idea that the emergent legibility of the past is an event in its own right, not something we can assume as a matter of course, or chalk up to the supposed progress of our knowledge. His own method of montage, inspired by Benjamin and using the weapons of legal history against his discipline’s imaginative limitations, provides an eloquent, erudite, and immensely suggestive meditation on Turner and on history.

Writing in 1863 amid the fires of the Civil War, formerly enslaved novelist, historian, and abolitionist Williams Wells Brown presented his own portrait of Turner as “a sketch of one whose history has hitherto been neglected, and to the memory of whom the American people are not prepared to do justice.” Probably relying on oral traditions, he incorporated tales of Turner’s early clashes with overseers and patrollers absent from The Confessions of Nat Turner, while also drawing on his imagination to write a speech that Turner might have delivered to the rebels:

Remember that we do not go forth for the sake of blood and carnage, but it is necessary that in the commencement of this revolution all the whites we meet should die, until we shall have an army strong enough to carry on the war upon a Christian basis. Remember that ours is not a war for robbery and to satisfy our passions; it is a struggle for freedom.

In a moment when, as Brown had it, “[e]very eye is now turned toward the South, looking for another Nat Turner,” that legibility was self-evident. What might it mean to reanimate the history of the Southampton revolt today, in a political climate marked by ongoing rebellions against the nexus of white supremacy and political economy? If racial capitalism calls for practices of countersovereignty, will these continue to require the productive difference between leaders and followers, faith and politics that is at stake in the matter of Nat Turner? To allow us to pose this problem in a new key, to speculate about our politics and what the “wild risk of change” might mean in the present, is not the least virtue of Tomlins’s speculative history. As Charles Burnett noted in his 2003 film essay on the divergent representations of the insurrectionary prophet, in fiction and history, “Nat Turner remains a troublesome property.”