One of the most anticipated books of the year, the first English translation of the early private notebooks of Ludwig Wittgenstein, was released this week. In a new review, professor Kieran Setiya examines how Wittgenstein’s personal life and philosophical views are deeply entwined in this document—sometimes literally, with frustrations (“Much anxiety! I was close to tears!!!!”) scribbled close to musings (“A question: can we manage without simple objects in logic?”). From his loneliness to his sexual habits, Wittgenstein’s personal life is also a matter of philosophical concern. “Not just philosophy, but philosophers,” Setiya writes. “That is what these notebooks help us to see. A philosophy of philosophers, even—shown, if not said.”

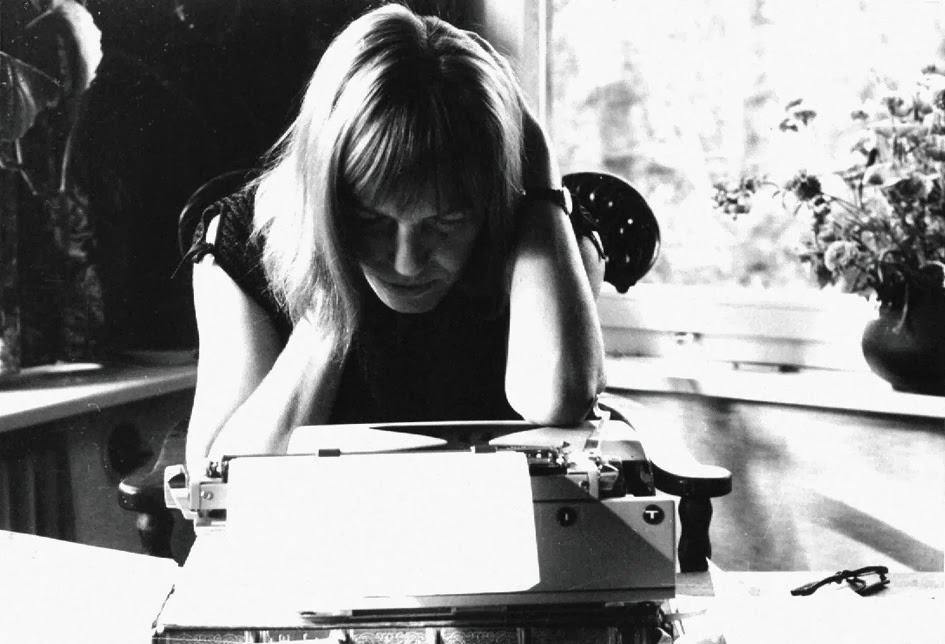

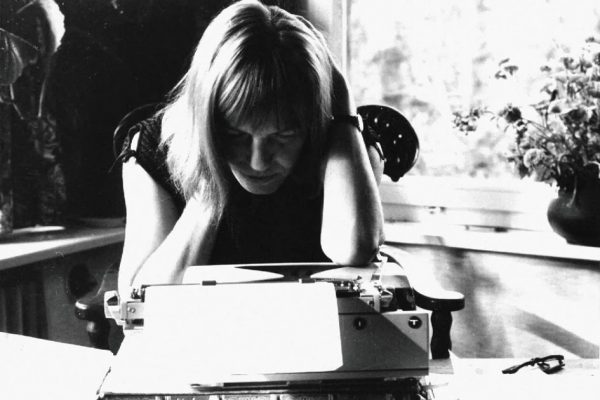

Setiya’s piece is one of three new Boston Review essays that foreground philosophical thinkers. All are prompted by recent translations or publications, such as Alan Wald’s review of the new Antonio Gramsci biography, in which he argues that the Italian Communist doesn’t fit into any established framework. Writing half a century later, Ingeborg Bachmann is perhaps best known as a poet and novelist, but she was also a serious student of philosophy and an influential commentator on Europe’s postwar intellectual scene. A new volume of Bachmann’s critical writings makes this dimension of her work available to English readers for the first time, and highlights her interests in naming and being. “What does it mean to be a person? The question may sound pat in an age so alert to the fluid nature of identity,” Bachmann translator Peter Filkins writes in his review. “But for Bachmann, writing in the wake of World War II, it was raw and real to the point of linguistic and psychological breakdown.”

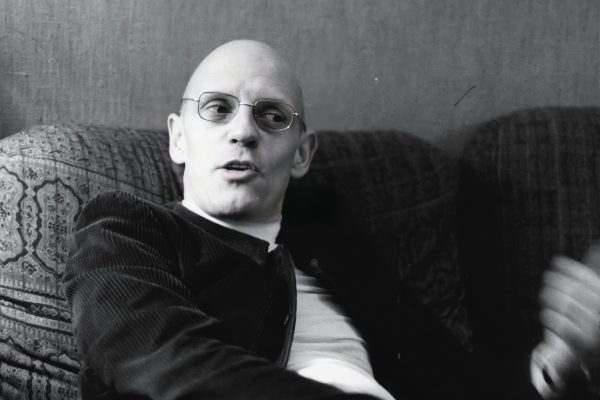

Other essays from the past year include a review of a new biography of Edward Said and a look at the recently released final volume of History of Sexuality—published against Foucault’s dying wish. Going back further, we’ve taken a dive into our archive to bring you our favorite philosophical profiles on a range of thinkers, from Hannah Arendt to Hans Blumenberg, Claude Lévi-Strauss to Charles W. Mills, Simone de Beauvoir to Spinoza. But we’ll leave the last word with Wittgenstein reviewer Setiya, whose comments served as the inspiration for this reading list. “Philosophers are an astonishing, flawed, obsessive bunch,” he writes. “We have something to learn—about them, and about their philosophy—from figuring out what makes them who they are.”

On the first English translation of Wittgenstein's early private notebooks.

On the first English translation of the Austrian poet’s critical writings, composed in the shadow of fascism.

For the Italian Communist, there was no road map for social transformation beyond hands-on, bottom-up activism.

His milieu was one of global, and specifically Palestinian, anticolonial struggle.

Simone de Beauvoir’s relationship with her readers was a mutually demanding collaboration.

Against the philosopher’s dying wish, the final volume of History of Sexuality has now been published. How should we approach it?

The structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss is in many ways still with us.

A recording of a virtual roundtable to honor the life and work of Charles W. Mills.

For the philosopher and intellectual historian Hans Blumenberg, myths and metaphors were pivotal to philosophical thinking, not opposed to it.

A new book suggests that modern readers can still follow the path of reason that Spinoza traced to true well-being, but they might not want to.