“Well‚ they’re paying attention,” Judge Lewis Kaplan said‚ after reading the jury’s note out loud. It was November 16‚ 2010‚ the third full day of deliberations in the trial of Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani.

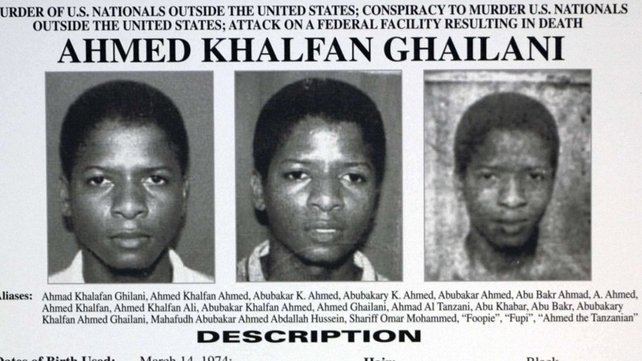

Ghailani was arrested in 2004 on suspicion of involvement in the August 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam‚ Tanzania and Nairobi‚ Kenya. After his arrest Ghailani spent nearly five years in CIA custody and at Guantánamo before he was brought to New York for trial at the U.S. District Court in Manhattan. Ghailani‚ prosecutors argued‚ was a member of al Qaeda who transported‚ among other things‚ gas tanks that were used in the bombings. The defense held that he was a dupe who did not know what the gas was for. He was charged with 285 counts‚ including one for each of the 224 deaths resulting from the attacks.

The case was critically important because the 36-year-old Tanzanian was the first Guantánamo detainee tried in a federal court. The trial was an opportunity to clarify the vexed issue of due process as applied to terrorism suspects.

And it had now come down to a very brief memo on a complex matter: “conscious avoidance” doctrine‚ which holds that an attempt on the part of a defendant deliberately to avoid knowledge of a conspiracy’s illegal purpose is identical to actual knowledge and therefore not an acceptable defense.

If‚ as Kaplan explained‚ “knowledge consciously avoided is the legal equivalent of knowledge actually possessed‚” and Ghailani avoided finding out what the oxygen tanks he fetched were ultimately for‚ was he guilty? If so‚ was he guilty of helping to make a bomb or of killing 224 people? And what of defense attorney Steve Zissou’s claim that there was no evidence Ghailani “did anything to avoid knowledge in this particular case”?

The jury asked: “Does this alleged illegal purpose have to be the illegal objective defined in each specific conspiracy count or simply be some illegal purpose?”

Michael Farbiarz‚ the lead prosecutor‚ jumped to his feet. “The purpose of the conscious avoidance charge,” he said‚ “is to suggest that someone who is participating in the conspiracy but is blinding themselves to its ultimate ends can’t use that as a bar to liability.”

Kaplan‚ the prosecutors‚ and the defense spent the rest of the afternoon debating the note. They slung case law at each other. Svoboda! Morgan! No‚ Svoboda shows the opposite! Tropeano! Samaria! After the sparring calmed‚ the court adjourned for the evening.

The next morning‚ Kaplan seemed to sense the attorneys’ weariness: “We’ve all read [the note]‚ we’ve spent all night reading it and trying to divine exactly what prompted it.” As he saw it‚ “The jury is satisfied that the defendant participated in the conspiracy and their issue is whether he did it knowingly.” Kaplan said Ghailani could be proved guilty only if the jury found he “knew of at least one of the unlawful purposes or objectives of the conspiracy . . . either because he in fact knew of that objective or because he consciously avoided [the] knowledge.”

At 5:45 that day‚ the verdict was announced. The jury cleared Ghailani on all counts except a single charge of conspiracy to destroy buildings and property of the United States. Throughout the trial‚ the defense successfully cast doubt on whether Ghailani could have known what was really going on. But some of the evidence could not be ignored. Armed with the judge’s instructions‚ the jury found its middle ground: Ghailani knew about certain illegal purposes‚ but not all. He helped to build a bomb‚ but not to plan a murder. He will spend the rest of his life in prison.