“My guts are out,” cried Abraham Vanhorn, mortally wounded during a fight between two gangs of drunk farmers. It was July 4, 1791, and the farmers were heading to dinner after a day of harvesting when two horses broke into the wheat field of John Crane. The angered Crane attacked the interloping horses, sparking a larger confrontation. Crane and Vanhorn “mutually agreed to box.” According to the local newspaper, Vanhorn proved “too powerful” for Crane, who, finding himself “bordering on a defeat,” drew out a pocket knife. In a “most dastardly and barbarous manner,” he thrust it at his opponent.

A long-forgotten case brought to life by legal historian Jessica Lowe in her new book Murder in the Shenandoah, Crane’s trial defined the period and has implications for criminal justice reform at present. Crane—a young, wealthy man who owned a 200-acre farm—claimed he was innocent. His father was the deputy sheriff of the county, and his wife’s relatives were some of the wealthiest and most politically connected people in the state. In contrast, Vanhorn was a wagon driver. He was respected, and he owned land, ten horses, and several slaves. But he was solidly middle class.

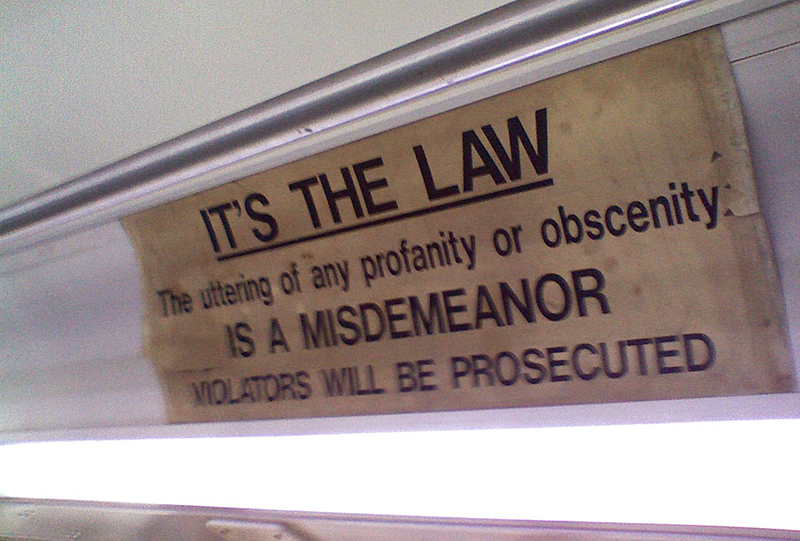

The misdemeanor system offers so many gradations of crimes that prosecutors have near-limitless discretion, and defendants often do not have the right to a trial or lawyer.

The case was a test of the new U.S. commitment to revising colonial laws and making criminal codes more democratic, less punitive, and less shaped by the class of the defendant. Virginia was not only a hotbed for such thinking, but was also the most populous state in the new country. What happened there ramified. And the judge in the case, St. George Tucker, was an eminent law professor, a thought leader in the “political experiment” of modernizing criminal law.

The case was as high profile as any trial of its day, with newspapers across the nation carrying reports. While criminal trials usually lasted only a single day, the defense and prosecution continued pleading their cases until midnight. The jurors then deliberated for forty hours. Some believed Crane was guilty of manslaughter, but not of willful murder. Finally, the jury reached a “special verdict,” finding Crane guilty but leaving it to the judge to decide whether it was manslaughter or murder.

In response, Judge Tucker sent the case up to the higher General Court, where it would be tried again. John Marshall, who would later become chief justice of the United States, argued Crane’s case. Crane lost his retrial, leading Marshall to petition the governor and council of state for a pardon. Letters poured in from family, friends, witnesses, and even members of the jury asking for Crane’s pardon. Crane’s family offered context that called for mercy: Crane was given to “lunatic” fits, a mental health condition that “appeared to be a kind of madness.” Nevertheless, the governor and council declined to pardon and Crane was executed “alongside a horse thief” the next year.

Four years after Crane’s execution, Judge Tucker led Virginia in a massive criminal law reform, focusing on the overly broad use of the death penalty. New indeterminate sentences were introduced, with the jury able to set a length that they felt would reform the criminal. The law also added new lesser degrees of crimes, such as second-degree murder, so juries would not be faced with all-or-nothing choices between capital first-degree murder and manslaughter. If those criminal justice reforms had been in place at the time, Crane would almost certainly not have been sentenced to death.

These sorts of reforms would eventually lead to the creation of our sprawling misdemeanor system. But law scholar Alexandra Natapoff writes in Punishment Without Crime that our criminal justice system now suffers a problem opposite to the one faced by Crane’s prosecutors: it offers so many gradations of crimes major and minor that prosecutors have near-limitless discretion, allowing prejudice and inequality to continue to shape prosecution in a different way.

The metastasis of our present-day misdemeanor system was driven mainly by racial logic.

The scale of the modern misdemeanor system is staggering: according to Natapoff, 13 million misdemeanors were filed in 2015 alone, making the misdemeanor system “four times the size of the felony system.” In fact, I would argue that it is magnitudes larger than that. In North Carolina alone, for example, there were almost 3 million traffic cases filed in 2015 and over 1 million defendants convicted. Many of these cases are filed as infractions rather than misdemeanors, and because Natapoff only counts formal misdemeanors in her data, her number does not reflect that every state has millions more of these sorts of cases every year.

In low-level cases, including in North Carolina’s infractions, people are jailed, impoverished by fines and fees, and lose housing and driver’s licenses, often without lawyers or any meaningful process. After all, since these are not felony cases, there may or may not be a right to a trial, and the courts themselves are often highly informal. The system—with nicknames such as “cattle herding,” “assembly-line justice,” “meet ’em and plead ’em” lawyering, and “McJustice”—massively “widens the rich-poor gap” and is invisible to those of us who can make bail or pay a fine. In misdemeanor cases, fines are often “the primary punishment,” but failure to pay them can result in further sanctions: an unpaid ticket becomes an additional fine, or a missed court date or parole appointment turns into jail time. This punishes people for being poor and creates a system Donna Murch has identified as modern-day debtors’ prison. As Natapoff writes, “It makes it a crime to do lots of things that poor people can’t help doing, like failing to pay fines, fees, speeding tickets, or car registrations.”

The system did not grow overnight, and unlike the reforms undertaken in the eighteenth century following Crane’s execution, the metastasis of our present-day misdemeanor system was driven mainly by racial logic rather than a reformist spirit. Natapoff identifies its origins in the Jim Crow South, where a slate of laws criminalizing everything from noise and vagrancy to being unemployed were invented as ways to extract convict labor from blacks, effectively re-enslaving them.

Despite serious constitutional concerns with, among other things, the way that the misdemeanor system imprisons people for poverty (which can be unconstitutional), courts have been slow to respond. In recent years, however, a handful of federal courts have found constitutional violations in court fee systems, cash bail practices, and driver’s license suspension schemes. Litigation challenging the use of cash bail for misdemeanor cases in Harris County, Texas, resulted in federal district court and appeals rulings, and the local judges adopting a new rule mandating quick release for misdemeanor charges. Just recently, the parties have agreed to a sweeping consent decree to impose long-term reforms and monitoring in Harris County.

Despite serious constitutional concerns with the way that the misdemeanor system imprisons people for poverty, courts have been slow to respond.

A growing band of progressive prosecutors around the country is leading a reconsideration of standard practices such as pre-trial bail, the imposition of fines and fees, and severe sentencing practices. Boston district attorney Rachel Rollins has announced a policy not just to decline marijuana possession charges, which others have done, but fifteen other low-level offenses as well. Philadelphia district attorney Larry Krasner has seen positive outcomes, with no change in recidivism, under a new approach recommending no cash bail in thousands of low-level criminal cases. Other prosecutors have adopted policies not to pursue charges in lower-level cases and have instead begun relying on diversion programs, to systematically move people to community treatment rather than criminal convictions. They have reconsidered sentencing policies in more serious cases as well, including in death penalty and life without parole cases. Efforts to provide defense lawyers is misdemeanor cases—one does not always have the right to a lawyer in these “off the record” lower-level courts—can also vastly improve fairness and outcomes.

Policing has changed as well. Natapoff describes how some police chiefs have moved away from arrests in misdemeanor cases. Using pre-arrest diversion programs, police seek to link individuals with behavioral health treatment and social workers, rather than make an arrest. Many use checklists of misdemeanor offenses that are presumptively diverted from arrest.

Some programs involve the cooperative work of lawyers, judges, local government, and community groups. Close to my home in Durham, North Carolina, the newly elected district attorney has been dismissing hundreds of cases to relieve individuals of court debt. The state courts have dismissed hundreds of thousands of old cases in the state. In tandem with these efforts, an innovative rights restoration program in Durham—a collaboration between city government, the district attorney’s office, Duke Law School, the Southern Coalition of Southern Justice, and many other groups—is working to expunge records and undo driver’s license suspensions. Similar programs have been created around the country.

The shift to community-based approaches is not being uncritically accepted. Some police, judges, and prosecutors have actively resisted these programs, as has the bail industry. Others argue the empirics, such as in debates about the use of risk assessment in criminal justice. There has been deserved criticism of the use of black box proprietary risk assessment (focusing, perhaps unduly so, on one such instrument, the Compas). That said, most such risk instruments are publicly available and can provide an alternative to our current default, which imprisons people who are too poor to afford bail or lawyers. New Jersey, for example, has seen a sharp drop in use of pre-trial incarceration after switching to the use of the Public Safety Assessment. Nonetheless racial disparities have persisted, and the courts have recommended further efforts to address them. In Virginia, my colleagues and I found many judges have not made use of risk assessment instruments to divert offenders to community programs; moreover, in many jurisdictions adequate resources do not exist for those treatment alternatives. Investing in such programs may produce greater good for the community and also save money long term.

Change is “happening right under our noses,” beneath the radar, in our petty offense cases, causing us to fundamentally rethink who counts as a criminal. The same tensions, between judges as guardians of liberty and “mere machines,” between more local control and state control, between rough justice and punishment, have been with us since the founding. New institutions need to grow to replace the machinery of mass incarceration. This work takes lawyers, judges, researchers, but also jurors and community groups and members of the public to get active—and increasingly they are. If the law is to move, we all need to push it along.