Lead Belly

Smithsonian Folkways, $99.98

(five CDs, cloth book)

Listening to Lead Belly uninterrupted for five hours, you get the feel of zigzagging across a forgotten country in a 1947 De Soto, eyes fixed on the landscape and fingers fiddling obsessively with the worn radio dial. It is a ghost radio, inhabited almost entirely by one voice and a singular-sounding twelve-string guitar. Every few mile markers reveals another variation, another invention, one more set of melodic lines that rolled out of the Louisiana bottoms and captured the alternative culture of an age.

“He wanted,” Woody Guthrie wrote, “to preach history, his own history, his people’s story and everybody’s history. He wanted to be all kinds of good names, a history speaker, a story teller, a talker, good fast walker, a loud yeller, and the man that was all big tone.”

Ghosts slip through the thick brown mesh of the single radio speaker. Musical revenants wander down the blue highways, the broad avenues of New York City, the narrow streets of Shreveport, the farm roads and packed dirt paths of a country still devoid of interstates. There is Silvy, with her endless pails of water, Texas Governor Pat Neff sitting on the warden’s porch, an unexpected Wendell Wilkie, Sweet Jenny Lee, Jean Harlow, Jack Johnson, Joe Louis, Queen Elizabeth, and Mr. Hitler, years before the world succeeded in “tearing his playhouse down.” And there, too, are all the anonymous singers that Lead Belly served time with, the men who taught him the songs that would be recorded by another generation and become part of our national soundtrack.

The Smithsonian’s in-house music label recently released its definitive compilation, Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection. It is an impressively comprehensive box set spanning the most productive years of a musician who arguably did more than any other to build the canon of American folk song.

Born in northwest Louisiana in the last days of Reconstruction, Lead Belly, a.k.a. Huddie Ledbetter, became “one of the musical giants of the 20th century,” according to Jeff Place, the Smithsonian archivist and prime mover behind the collection. No one familiar with the development of folk, blues, and the music that emerged from them could disagree. “Since his death, his songs have lived on,” Place writes in the 140-page book accompanying the collection, five CDs featuring 108 tracks, some never previously released. “Every self-respecting ‘American folksinger’ performs them.” The same is true of rock and rollers all over the world.

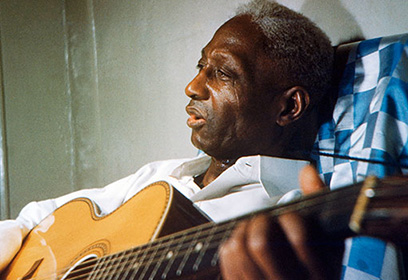

There was an aura about the man. When Lead Belly performed, people listened.

“He was what musical scholars call a ‘songster,’ able to dig into his bag of tricks to entertain any audience,” Place writes. For the most part, he played songs he learned from others, not his own compositions. But all of it was his music.

As the collection demonstrates, that music is various, encompassing country blues, work songs, spirituals, prison laments, children’s songs, and ancient Anglo broadsides. The subjects are just as diverse, ranging from love and murder to disaster, frolic, injustice, topical issues, and work so hard that it is past imagining.

While Lead Belly was too curious, too peripatetic, to restrict himself to a single genre, he could play the blues as well as his less eclectic peers. Beginning in 1912, when he would have been about twenty-four years old, he traveled through Texas with Blind Lemon Jefferson for some years. He no doubt learned much of the country blues vocabulary from the younger but more experienced musician. He continued to play with blues musicians after parting ways with Jefferson: Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Pops Foster, and Willie “The Lion” Smith accompany him on a number of songs from the Smithsonian archive.

The book includes rare photographs of Lead Belly, extensive biographical material, memorabilia, and correspondence from other musicians, notably Guthrie. There are also illuminating passages from Tiny Robinson, Lead Belly’s niece and founder of the Lead Belly Foundation. For a bluesman, he made it to a ripe old age—sixty-one. It was, Robinson writes, a “bad, good, hard, and easy life.”

In his essay for the collection, music historian and Grammy Museum Executive Director Robert Santelli calls Lead Belly “a man of contradiction and complexity.” Certainly, the musician’s relationship with the folklorist John Lomax was as fruitful, troubled, and complicated as could be.

In 1933 Lomax “discovered” Lead Belly at Louisiana’s infamous Angola prison and recorded the first acetates. Without Lomax’s recordings, an invaluable part of America’s musical heritage would have been lost forever. It took fortitude and courage to traverse the rural South recording the imprisoned and disenfranchised.

At the same time, Lomax—who was born in Mississippi just two years after the conclusion of the Civil War—had a tendency to treat Lead Belly as chattel. Lomax didn’t trust Lead Belly with money and often deprived the artist of royalties. One time when he did pay overdue earnings, he backdated checks to the songster’s wife, Martha. In his publications, Lomax took credit for music and lyrics he had not created and was not entitled to.

Lomax proved insensitive, also, to the conditions in which Lead Belly and other prisoners lived. In his introduction to American Ballads and Folk Songs, published in 1934, Lomax writes, perhaps to convince himself, that despite the “forbidding iron bars, the stripes, the clank of occasional shackles” and the “cruel-looking black bullwhip four feet long” at the prison farms he visited, he saw “no evidence of cruel treatment.” He seems nonplussed by the “hopelessness” and “melancholy” expressed in the songs. One can only conclude that he was a better judge of musical talent then he was of prisoner welfare.

Among the hundreds of incarcerated musicians Lomax recorded, many were talented choral and solo performers. But there was something about Lead Belly’s music that he immediately recognized as unique. To begin with, there was the instrument—Lead Belly accompanied himself primarily on an acoustic twelve-string guitar. This instrument, rare then and not all that common today, creates a very different sound than the generic six-string. It is louder, fuller, often described as shimmering and resonant. Place quotes the folk musician Fred Gerlach: “A discussion of Lead Belly’s music is not complete until people understand the power, raw and total, which Lead Belly unleashed in his 12-string play. Lead Belly’s aura was considerable, it encompasses his song and falls upon one’s ears and being.” He said the sound of the twelve-string reminded him of a barrelhouse piano. Although he is identified with the instrument, he was known to play piano, mandolin, and fiddle as well. The collection includes three recordings of him on the “windjammer,” a Cajun accordion.

Lomax may also have recognized that Lead Belly’s music was less provincial than that of his fellow inmates. He was familiar with work songs, of course, and he often sang chronicles of prison hardships. But he could learn a song and instantly change it as he saw fit. Even in the first prison sessions, it was clear that his selection was more wide-ranging than his peers’.

Then there was the voice. Higher than you would expect from such an imposing figure, it was perfectly suited to the range of his repertoire. He had an uncanny ability to tailor the sound of his voice to the subject of the song, encompassing the (almost) sweetness of “Goodnight Irene,” the resigned sorrow of a traditional blues, the solemnity of a childhood spiritual, and the unconcealed fury of “The Bourgeois Blues.”

And as Gerlach said, there was an aura about the man as he performed. It is an ineffable, indefinable quality, but common to great musicians. When Lead Belly sang, people listened.

It is unlikely that Lomax took all these qualities in at one or two sittings, but the folklorist had an intuition that served him well for decades. In 1935, shortly after they met, Lomax said of his prodigy:

Northern people hear Negroes playing and singing beautiful spirituals, which are too refined and unlike the true southern spirituals. Or else they hear men and women on the stage and radio, burlesquing their own songs. Lead Belly doesn’t burlesque. He plays and sings with absolute sincerity. Whether or not it sounds foolish to you, he plays with absolute sincerity. I’ve heard his songs a hundred times, but I always get a thrill. To me his music is real music.

Perversely, in his desire to publicize Lead Belly’s music and burnish his own reputation, Lomax helped to market Lead Belly as a sort of savage savant. His criminal past was vital to his legend; he grew famous not only for recording classic songs but also for picking and singing his way out of prison.

Lead Belly’s first brush with the law came in 1915, when he wound up on a chain gang for thirty days. But the real time began in 1918, in Sugar Land, Texas. He was convicted of murder, though he claimed self-defense. Governor Neff had a habit of visiting the prisons, and when he stopped by Sugar Land in 1925, Lead Belly wrote and performed a song for him. So moved was he that Neff promised to pardon Lead Belly on the last day of his governorship, which he did. The Folkways text reproduces a yellowed copy of the official pardon. In spite of the documentation, the state took the formal position that Lead Belly had been released after completing his minimum sentence.

Then, in 1933, Lomax and Lead Belly had their fateful meeting at Angola, where the musician was again incarcerated, this time on a conviction for attempted murder. Once more, Lead Belly claimed he was defending himself from men who had jumped him. He wrote another song, for Louisiana governor O. K. Allen, and was released. The state maintained that he was let out for “good behavior.” There is no evidence that Allen heard the song, though Lomax apparently did deliver it to his office.

He could sing sacred songs with utter conviction and move right on to ‘Pigmeat.’

For Lomax and the press, these stories were, perhaps understandably, too good not to capitalize on. The most egregious of these attempts was a 1935 reenactment from the March of Time newsreel series, purporting to describe Lead Belly’s release from Angola.

In the newsreel, Lead Belly is presented as humble supplicant and Lomax his noble savior. The footage opens with Lead Belly concluding a version of “Good Night, Irene.”

Lomax: That’s fine, Lead Belly. You’re a fine songster. I never heard so many good nigra songs.

Lead Belly: Thank you sir, boss. I sure hope you send Governor O. K. Allen a record of that song I wrote about him. I believe he’ll turn me loose.

Lomax, looking as exasperated as his feeble acting skills allow, ensures Lead Belly that he will do what he can. The musician then asks Lomax for a job, which Lomax reluctantly agrees to. Lead Belly swears his undying affection and loyalty: “I came here to be your man,” he says in the halting cadence of one unaccustomed to the camera, “I got to work for you the rest of my life.”

In a story about the arrival of Lomax and Lead Belly in New York, the New York Herald Tribune repeated the tales of the two singing pardons as fact. “Sweet Singer of the Swamplands Here To Do a Few Tunes Between Homicides,” the headline read. Life’s Lead Belly headline was less alliterative but even more direct: “Bad Nigger Makes Good Minstrel.”

For a short time, Lead Belly served primarily as Lomax’s chauffeur. But they parted ways, acrimoniously, over a contract dispute involving musical rights, and the singer returned to Louisiana.

With the help of Alan Lomax—a folklorist like his father, but far more attentive to what he called “cultural equity”—Lead Belly eventually returned to New York and developed relationships with Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and the nascent leftist folk community. While he performed and socialized with them, Lead Belly was not particularly interested in their politics. In fact, he wrote a campaign song for Wendell Wilkie, a pro-business Republican and adversary of much of the New Deal. What likely attracted Lead Belly to Wilkie was his progressive stance on race relations. In a 1942 address to the NAACP, Wilkie criticized both major parties for ignoring “the Negro question.” “The desire to deprive some of our citizens of their rights—economic, civic, or political,” Wilkie claimed, “has the same basic motivations as the Fascist mind when it seeks to dominate whole peoples and nations.” Wilkie also worked with the NAACP to change the portrayals of African Americans in movies. Lead Belly, long an aficionado of cowboy songs and westerns, thought he might benefit from that effort, once traveling to Hollywood to try for a part. A younger man was hired in his stead.

Perhaps he longed to play beside Gene Autry, the country singer and star of more than a hundred formulaic westerns, whom he admired. Both recorded the other’s songs. More importantly, what drew Lead Belly to Autry was the same quality that fostered his affinity with Wilkie—Autry’s support for racial equality. Autry had developed a set of principles called the Cowboy Code, the fifth tenet of which held that adherents “must not advocate or posses racially or religiously intolerant ideas.” Mild words today, but striking from a mid-twentieth-century country singer.

Lead Belly’s biography wouldn’t much matter had he not made extraordinary music, and the handsome Folkways compilation is unique in presenting the full scope of it. While the man is not an obscurity newly brought to light, the collection nonetheless includes unexpected pieces—the cowboy songs stand out, as do two 1941 WNYC radio shows, particularly the second, in which Lead Belly is accompanied by the delightful Oleander Quartet.

Also included are a show tune, lesser-known work songs and murder ballads, an account of the Hindenburg disaster, and the most unusual take on the sunken Titanic you will ever hear. Many black musicians sang ironic lamentations of the great ship, on which no blacks died because none were allowed aboard. Lead Belly’s song is not ironic, though. More like jubilant. Oddest of all, perhaps, is the previously unreleased song he wrote for Queen Elizabeth’s nuptials with Prince Phillip. As far as I can tell, Elizabeth and Phillip are the only subjects of a Lead Belly composition still living.

There is in addition the prescient “Been So Long (Bellevue Hospital Blues),” describing Lead Belly’s stay in the hospital, which he recorded some years before he would die in that institution of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

One of the most powerful blues songs in the collection is “Backwater Blues,” a Bessie Smith number long thought to be—with Charley Patton’s epic “High Water”—an account of the Mississippi flood of 1927, which killed hundreds and inundated 27,000 square miles of largely agricultural terrain. However, it now appears Smith was writing about a similarly destructive Cumberland River flood, which had occurred several months earlier. Whatever the case, Lead Belly’s traditional rendering of the tragedy is as bold as Patton’s or Smith’s.

These disasters altered blues music in significant ways. They not only provided subjects for songwriters but also hastened the migration of African Americans out of the Deep South. Those who settled in Northern cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and New York developed a more electrified and urbane sound. Meanwhile, interest in the country blues that evolved in the Mississippi delta waned quickly.

Like a lot of blues players, Lead Belly also sang spirituals. Several are included in the Smithsonian compilation. Some, such as “We Shall Walk Through the Valley” and “Didn’t Old John Cross the Water,” are staples of the canon. There are two versions of the mysterious and poignant “Ain’t Going Down to the Well No More,” which has also been described as a field holler. The second version, which lasts a little more than a minute, is an a cappella rendering containing the lyrics, “I’m a true believer / I’m a true believer / And I ain’t going to the well no more.” It is hard to say whether the song testifies to faith or despair.

American musicians from Skip James to Al Green have struggled with the conflict between secular and sacred music. At points in his career, Reverend Gary Davis, who came to prominence performing a Lead Belly tribute concert, refused to play the blues at which he was so skilled because he found it at odds with his Baptist beliefs. But Lead Belly could sing the sacred songs, most of which he had learned as a child, with utter conviction and move right on to “Pigmeat” and “Black Betty,” which make the Folkways cut, or “I’m Gonna Hold It in Her While She’s Young and Tender,” which doesn’t. He did not appear to suffer undue torment from the contradictory impulses.

That the sturdy, stern-looking ex-convict enjoyed recording children’s songs is yet another testament to his versatility and songster mentality. “Ha-Ha This a Way,” perhaps the best known of these tunes, is included here. Lead Belly said he learned this song in school, where it was sung to accompany a “ring game” played at recess.

In notes to an earlier series of 78s Lead Belly recorded for children, Place recounts the always-outraged Walter Winchell turning his venom on the singer and wondering how “anybody could put out a record for children sung by a murderer.” Moses Asch, the producer of that record, took the comment in stride: “Well, Walter Winchell . . . gave me full publicity on this thing,” he later said. “I got more publicity on that than anything I’ve ever done since or ever.” As ever, bad publicity was better than no publicity at all.

Lead Belly’s career was full of bad timing, shoddy management, and a curious combination of poor judgment and perseverance. The split with John Lomax left him adrift in New York for a time, which included another prison stint, until he rebounded stronger than ever. Still, as this encyclopedic set demonstrates, his ability to sing for everyone—to conjure an entire country over decades—was a sort of musical miracle, for which he was eventually celebrated. Listening to these five discs, one is constantly reminded of the extraordinary range and depth of his influence. It would be wasteful to list everyone who has recorded Lead Belly’s songs; just take a look at your record collection. Better still, listen to him perform them, which is that much easier to do thanks to the Folkways set.

Yet, for all the joy this superb collection will bring listeners, it is important to remember that Lead Belly continued to sing in spite of the mistakes he made, the oppression he endured, and the hardships that never seemed to abate. In her idiosyncratic prose, Tiny Robinson describes the difficulties Lead Belly—and countless other African American musicians of his era—faced, powerfully and finally:

Some of the thing was; the environment, which he was, brought up under. Don’t do this, don’t do that, be careful what you say, and where you go, you have no right walking down that road where those folk live, and stay on this side where you belong. He was connected with those series of episode soon as he was able to walk a block by myself. I have my people to sing about. The way they struggle and nothing seem to be coming their way. Nothing was done to improve the matter. The violent grasp was too strong for us to escape. So we had to sang about them.