In the current issue of Boston Review, Archon Fung and Anthony Fowler express related but distinct fears about how politicians manipulate the voting public. Fung worries that “big data” will make it possible for politicians to micro-target subsets of the electorate, effectively replacing political deliberation with a “fragmented aggregation of individual views”; Fowler argues that because get-out-the-vote efforts work best on voters who are already fairly engaged, they exacerbate inequality in political representation.

Fowler’s findings reinforce Fung’s argument, showing why his concern is valid and pressing. The kind of supercharged micro-targeting Fung describes represents an incremental improvement on tactics that campaigns have been using for years, but Fowler’s research indicates that those tactics have already contributed to political inequality and done damage to our democracy.

Fung’s idea that data analysis will allow politicians to divide and conquer the public is at least as old as Eugene Burdick’s 1964 novel The 480. Inspired by an actual predictive analysis of the 1960 election by the Simulmatics Corporation, the book imagined a 1964 presidential election in which political operatives use computer simulations to predict and manipulate the electorate’s behavior. Although computer simulation is no longer novel, the anxiety Burdick expressed is still evident in the periodic coverage of studies that purport to show that voting behavior can be predicted by characteristics as trivial as pet preferences or candidate attractiveness. Few would be shocked to learn that voters are swayed by factors other than policy preferences, but the fear is that big data techniques will allow politicians to tap into these hidden influences and manipulate the electorate invisibly.

If campaigns have reached that level of sophistication, however, they have hid it well. In theory, politicians could already make use of the granular targeting available through social media and online advertising, but old media continue to dominate campaign spending. In the 2012 election cycle, federal campaigns reported spending less than $50 million of their $3 billion budget on data of all kinds (email lists, donor histories, voter files, etc.), and spent about five to ten times as much on broadcast media as on online advertising. (These numbers come from my analysis of Center for Responsive Politics data, and are imprecise because they are based on the vague descriptions campaigns provide to the Federal Election Commission.) The Obama campaign, which likely used analytics more extensively than any campaign in history, still seems to have spent most of its money on broadcast.

Even the Obama campaign’s impressive data mining operation still represented only a marginal improvement on classifying voters the old-fashioned way. As political scientists John Sides and Lynn Vavreck have argued, already-public information such as party affiliation and turnout history predict voter behavior much more effectively than even the most accurate consumer data. Since candidates in 2012 generally opted for broad appeals rather than demographically specific ones, this might imply that micro-targeting doesn’t imperil the national conversation about politics after all.

Unfortunately, that conversation is already on life support. Only about one-third of Americans read a newspaper every day, and in 2012, just 27 percent of Americans reported getting news from a political blog or website in the past week. Few Americans claim to follow “very closely” stories that are not above-the-fold headlines, even ones with a strong partisan valence and widespread coverage such as the Keystone XL pipeline (16 percent of Americans as of March, per Gallup) or last year’s IRS scandal (20 percent as of May 2013). That small population of news junkies likely overlaps the minority of Americans who are devotees of Fox News or MSNBC, further diminishing the number of citizens engaging in actual political dialogue. For better or worse, our politics are already fragmented.

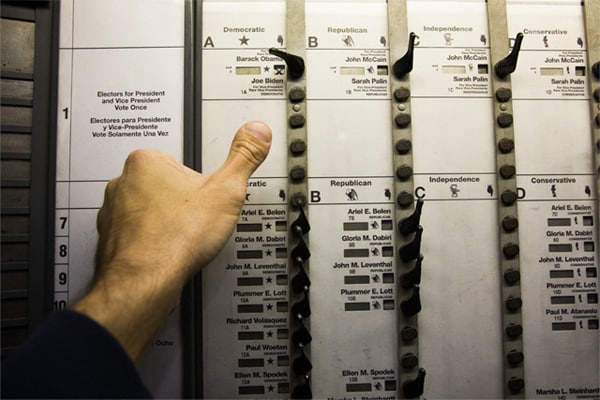

The extent of the gap between the politically engaged and disengaged is what makes Anthony Fowler’s findings troubling. He and his coauthors report that get-out-the-vote operations “increase representational inequality” by bringing “more rich, white, educated, churchgoing citizens to the polls.” Knowing that their efforts are more likely to affect some than others, campaigns assign “propensity scores” to prospective voters in order to zero in on those who just need a nudge to vote.

This is where big data is most valuable. The Obama campaign’s major analytical accomplishment was to improve propensity scores by combining traditional voter rolls with consumer data and huge numbers of voter contacts, but even before Obama’s 2012 campaign, political operatives were getting much better at honing in on the best prospects among potential voters. For example, political scientist David Nickerson, who served as Director of Experiments for the Obama re-election campaign, has demonstrated that voter contact in Ohio was vastly more concentrated among high-propensity voters in 2008 and 2012 than in 2004—a triumph of intelligence-gathering from a campaign’s perspective, but one that reinforces political inequality. The better campaigns get at concentrating resources on prospective voters, the more they can focus on turning out their base and the less they need to worry about broad mobilization. Senate Democrats have apparently already adopted this strategy to some extent, according to Sasha Issenberg, who says that candidates’ strategy for this November is to “mobilize their way into contention, then persuade their way across the finish line.” In short, even if big data doesn’t inaugurate an era of personalized campaign messaging, it’s already fragmenting our democracy in another way by widening the gap between the engaged and the disengaged.

Data and analytics are only tools; under the right circumstances, they can help rectify political inequality instead of reinforcing it. For example, Nickerson points out that one of the most common ways campaigns use external data is to find updated phone numbers, which let campaigns more vigorously pursue hard-to-reach voters. In this way, data gathering can act as a force multiplier for old-fashioned field operations. If this strategy proves effective, it could help reverse the decades-long trend of replacing person-to-person voter contact with mass media. Political scientists Donald Green and Jennifer K. Smith argue that the depersonalization of campaigning accounts for much of the drop in turnout over the last fifty years; big data could help reverse that decline.

On the other hand, a return to person-to-person campaigning wouldn’t necessarily address Fung’s concern about fragmentation, since the scripts that human canvassers use are just as customizable as Facebook ads. Organizations that, unlike campaigns, do care about things like participation and deliberation for their own sake could theoretically make use of some of the tools described above, but such organizations are less numerous and not as well funded as campaigns. Moreover, the techniques that work so well to persuade citizens to vote or sign a petition—one-off actions—may not be enough to build the more lasting habits of engaged citizenship.

Ultimately, whatever use campaigns are able to make of our personal data, they only represent a fraction of the contact most voters have with the political world. Campaigns only contact voters during a small portion of each two-year cycle, and only reach a minority of the electorate; fewer than a quarter of “likely voters” (let alone the unlikely or unregistered) reported being contacted by the massive Romney and Obama operations in 2012, for example. Most voters are therefore probably much more likely to come into contact with politics through conversations with friends and family, cable news, talk radio, social media, or any number of other sources. These experiences are the ballast for our political beliefs, creating a political identity that campaigns can only sway on the margins. Consequently, the techniques that campaigns use to carve up the electorate are less worrisome the more robust the political culture; if Americans were more likely to discuss politics, engage in civic activism, or participate in other ways besides voting, they might be less likely to be influenced by campaign tactics. As long as politics remains a niche interest, we have reason to be concerned about the campaign tactics of the future, but much more reason to worry about the present.