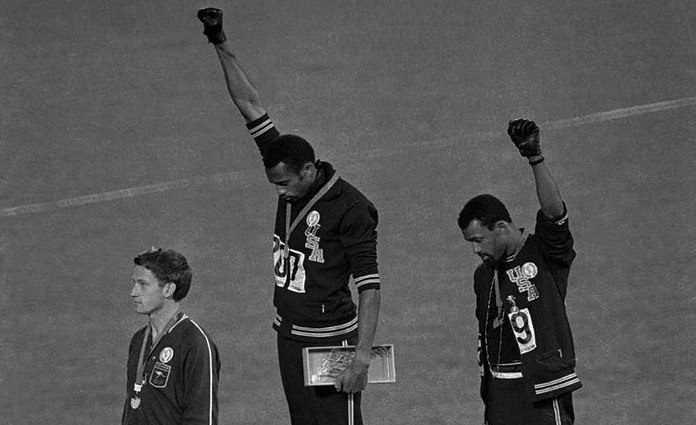

1968, as Herbert Marcuse put it, was the year of the Great Refusal—a “public moment,” to echo French revolutionary Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, when the social contract was challenged. Allen Ginsberg chanted “Om” amidst the police riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The Beatles released The White Album. Muhammad Ali, the heavyweight champion of the world, was denied a license to fight because he opposed the war in Vietnam. The Women’s Liberation Party protested the Miss America pageant, affirming that women are people, not livestock. Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, and Bob Marley made reggae music in Jamaica, and the whole world danced. At the Olympics in Mexico City, just months after the massacre of hundreds of students in Tlatelolco, the fastest men alive bowed their heads and raised their arms and joined their fingers into fists of black power and workers’ struggle.

Rebels could read the writing on the walls. The graffiti of Paris took the imagination to unprecedented heights against the imperialist Leviathan: “soyez réalistes, demandez l’impossible” (“be realistic, demand the impossible”). Turning the world upside down required turning the police command, “Up against the wall, mother fucker,” back on the police themselves. Below it all was an infrastructure wrought of rubber, iron, chrome, coal, oil. On them was built the Keynesian model of economic development and the Fordist model of work. The speed-up on the auto assembly line killed workers and stuffed gas-guzzling vehicles onto the asphalted highways.

Looking back on 1968, I see two big themes in conflict—thanatocracy versus the commons. My reflections are part reminiscence and part commentary on two revolutionaries of the time, Guyanese historian Walter Rodney and American writer Grace Lee Boggs.

In 1968 I was a graduate student in history, and I helped occupy one of the five buildings occupied at Columbia University in April. The first one, Hamilton Hall, was named after Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and the key figure responsible for the capitalist transition from the slavery of the Caribbean sugar plantation to the slavery of the U.S. cotton plantation. It was with poetic justice that Hamilton Hall was occupied by the descendants of slaves, the Students’ Afro-American Society. The Students for a Democratic Society took the next building (Low) and then another (Math). A fourth building (Avery) was taken by architecture students, and a fifth—Fayerweather—was taken by graduate students in the arts and sciences, including those of us in history.

In the universities, in the schools, in the libraries, in the movies, radio, and television there was no African American history to speak of.

We opposed the university’s plans to enclose a commons, a park used by Harlem residents, in order to build a gymnasium for the well-to-do white students of the university. We also opposed the university’s Institute of Defense Analyses, with its direct association with the Pentagon and the imperialist war machine. Our actions came on the heels of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the protests that erupted in city after city. Our actions also followed by two months the commencement of the Tet offensive in Vietnam and the stunning capture of the cultural and ancient capital, Huế, as poorly armed Vietnamese foot soldiers held off the artillery of a technological giant.

On the night before the surprise attack on Huế, Việt Cộng commanders told their troops that the battle “will bring forth world-wide change,” and so it proved. Bill Sales from the Students’ Afro-American Society spoke to us: “You strike a blow at the gym, you strike a blow for the Vietnamese people. You strike a blow at Low Library and you strike a blow for the freedom fighters in Angola, Mozambique, South Africa.”

We not only seized five buildings, which we held for a week. We also seized faculties of knowledge. The bourgeoisie maintains its dominance by the nature of the knowledge it imparts to students. “The true fortress of class influence,” Louis Althusser said, “is the university.” Again the students in Hamilton Hall led the way by renaming the building “Nat Turner Hall of Malcolm X University,” two names inseparable from the militance of revolutionary change.

Few people in 1968 had heeded Malcolm’s injunction to study history. He showed that the ideologies and culture of white supremacy depended on deliberate ignorance and cultivated amnesia in the service of slavery. In the universities, in the schools, in the libraries, in the movies, radio, and television there was no African American history to speak of. Few people knew that Nat Turner had led a rebellion of liberation in 1831, based on his experiences on a slave plantation and inspired by his reading of the Bible. The critique of ideology and the occupation of buildings went hand in hand.

For me this meant history. Only a month before King’s murder on April 4, The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders had released the Kerner Report, named after its chairman, the governor of Illinois, with its famous conclusion: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” What about class analysis, I wondered?

I went into 1968 as a New Leftist. My goal was the human equality and dignity which true communism promised, at least in theory. The means of attaining it was the working class, who alone could expropriate the expropriators. Struggle was a process, and it obviously included slavery, and perhaps even more obviously, but rarely acknowledged, it included the labors of reproduction—the unpaid labor of women. We know this now only because a generation of African American and women scholars have fought the battle of ideas. 1968 was a year of “history from below,” advancing the fight to establish African American history, women’s history, and labor history.

As an apprentice historian I was repelled by the conservative nature of the Columbia professoriat and blown away by the English historian E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963, revised 1968). The book restored the redemptive power of the working class in its struggles. Likewise The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) had shown that the so-called “criminal” could become a figure of social change. I found these two themes at work in the eighteenth century. Not only Thompson but Marcuse too reached back to the period, concluding that “the ghettos can be compared with the faubourgs of Paris.”

Malcolm showed that white supremacy depended on deliberate ignorance and cultivated amnesia.

Already in the Fayerweather Commune, as we styled ourselves, exuberance, love, and solidarity were the mood, despite the terror that awaited us from nocturnal police violence and their matraqs (“club” in Algerian Arabic—as Zakir Paul notes, “the preferred weapon of the police against both the pro-Algerian demonstrators in 1961 and the activists of the mass movements of May 1968”). At Fayerweather Hall, we brought food into the building in baskets pulled up from supporters on Amsterdam Avenue. We were not the only building provisioned by the Harlem community. “We knew we were catching a peek of another universe,” Columbia student Hilton Obenzinger recalls, “and that glimpse would keep us solid, whole, honest—and that vision turned us into a commune.”

We called ourselves a commune in solidarity with the communards of Paris. At the time we were just barely beginning to think about the relationship between the practices of commoning as a means of social subsistence and the commune as an attempt to scale up principles of mutuality and equality to society as a whole.

We saluted Paris. With a wide brush I painted “Dessous les pavés c’est la plage” on the wall. And Paris saluted us. Che Guevara was murdered by agents of American imperialism in the Bolivian highlands the previous autumn. He had said, “Create Two, Three, Many Vietnams!” We were thrilled when newspapers in Paris printed a photo of a French student holding a placard with a new version of Che’s slogan: “Create Two, Three, Many Columbias!”

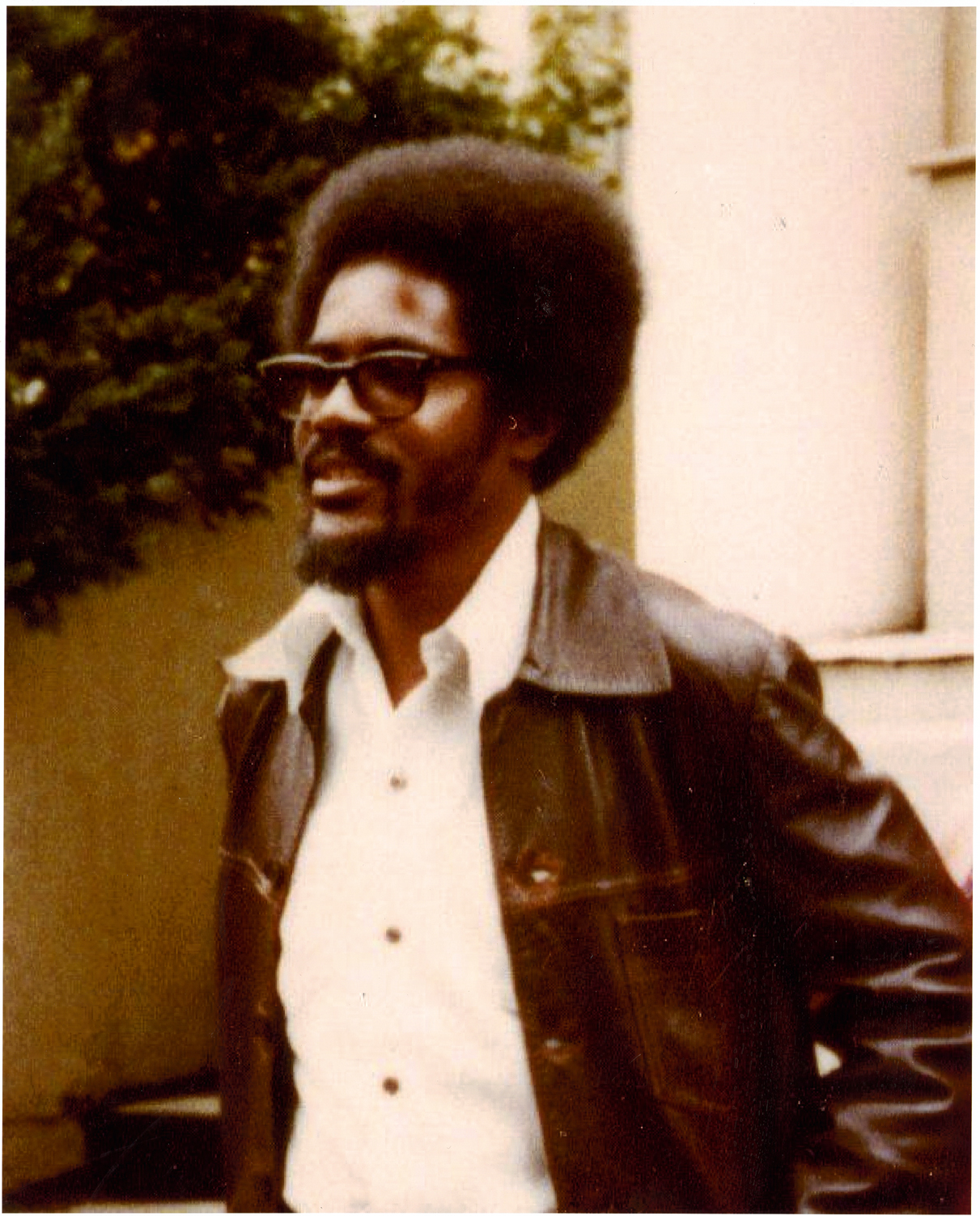

I don’t know whether Walter Rodney met with Che Guevara when the young, brilliant, revolutionary history student visited Cuba in 1962. I do know that Rodney’s talks—he called them “groundings”—to students, to Rastafarians, to the poor people of Kingston’s gullies, to the followers of Jamaica’s Reverend Claudius Henry—known as R.B. (“Repairer of the Breach,” as Isaiah 58:12 has it)—so frightened the Jamaican authorities that in October 1968, one year after Che’s death, they declared Rodney persona non grata. What frightened them? Perhaps Rodney too was a repairer of the breach—he shared the vision described by the prophet. Rodney had answered the question himself at the time: “What was discussed obviously bothered the regime, because I did not hesitate to raise the question of revolutionary social change.”

Rodney was invited to the Congress of Black Writers meeting in Montreal in October 1968. The letter of invitation called attention to the “fantastic outburst of the peoples of the world.” It asked,

Where then does the Black emancipation movement fit into this objective world situation? . . . What must we do and how must we achieve our objectives as Black people in a changing objective world? This is the purpose of the Congress of Black Writers.

Earlier in 1968 Rodney had observed that “the consciousness among students as far as the racial question is concerned had been heightened by several incidents on the world scene—notably, the hangings in Rhodesia and the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King.”

Walter Rodney / Walter Rodney Foundation

In 1968 the U.S. ruling class thought in terms of death and data, “body counts” and “kill ratios.”

We had heard about King’s murder. Many of us had joined him and accepted in our philosophical discussions the goal of “the beloved community.” We knew he opposed imperialism, as he opposed racism and the consumer society—the triple evils. King’s goal, as American activist James Boggs—husband of Grace Lee—wrote, “was integrationbut his strategy was confrontation, and in the actual struggle the first was turned into its opposite by the second.” We knew he was murdered while advocating for the sanitation workers who had been subject of exploitation and mechanized forms of violence in their working conditions.

But what were the hangings in Rhodesia? We in white America had not heard about it.

On March 6, 1968, three men were hanged: James Dhlamini, Victor Mlambo, and Duly Shadrack. Dlamini and Mlambo were in a black nationalist commando unit called the Crocodile Gang, formed in 1964 in exile in Zambia. They had been convicted of killing a white motorist on June 4 of that year. The victim, Pieter Obeholzer, was a foreman at a wattle company. Although Queen Elizabeth II reprieved the three men, the lawless white supremacist regime of Rhodesia hanged them anyway.

Outside the United States, the hangings were global news, the issue of the day. There was a moment of silence in Indian parliament, rioting took place in Accra in Ghana, and questions were asked in the House of Commons in the United Kingdom. Rhodesia’s breakaway regime’s 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was itself a huge political issue. Kwame Nkrumah raised it in the United Nations, and the Organization of African Unity threatened to break off ties with the U.K. for acquiescing to it. The UDI threw into question the whole Commonwealth project and the U.K.’s commitment to a fair deal for former colonial peoples.

The Wattle Company of eastern Zimbabwe was founded in 1945, producing kiln-dried timber for export. In 1956 its factory for producing wattle extract was commissioned in Chimanimani. Extraction of forest products depended on the 1951 NativeLand Husbandry Act, which was “based on the premise that production in theAfrican reserves would be boosted by a system or private ownership ofland rather than the communal or customary rights to land that hadexisted hitherto.” State terror in the form of hanging had become associated with the enclosure of the common lands.

Murder and hanging raised the consciousness of the Jamaican students. Looking back on it we can see them as aspects of thanatocracy. In 1968 the U.S. ruling class thought in terms of death and data, “body counts” and “kill ratios.” The massacre at My Lai took place 16 March 1968. Perhaps the most famous photo of the Vietnam war appeared on February 1. It showed the South Vietnamese police chief shooting a Viet Cong prisoner in the head at point blank range. The number of people on death row in the United States was 517. By 1982 it had doubled to 1,050. Within another six years it had doubled again, and at the beginning of this century it included three and a half thousand. It has hovered around 3,000 ever since. War, death row, lynching: the various forms of social and political death belong to the science of thanatocracy, and they have a deep historical continuity as well as a vivid presence in the work, for example, of Black Lives Matter. Rodney was fully alive to such summations of social oppression. The Rhodesian hangings and King’s assassination are symptoms of a civilization based on death. Inspired by the contradictions of 1968, Marcuse summed up human history as a conflict between two human instincts, Eros and Thanatos.

Impelled by these findings a new look was cast on John Locke, the political theorist of private property. His comments on the death penalty no longer were theoretical. Sovereignty itself depended upon it. The power of legislation was defined by it. It could be executed for stealing a coat. This was the Caesar-like theory of thanatocracy, or government by death, symbolized by icons of church and state—the sticks and axe of the fasces, the cross bars of the crucifixion.

The first act of the Paris Commune in 1871 was the destruction of the guillotine and the abolition of the death penalty.

Percy Shelley had written, “The first law which it becomes a reformer to propose and support, at the approach of a period of great political change, is the abolition of the death penalty.” The first act of the Paris Commune in 1871 was the destruction of the guillotine and the abolition of the death penalty. The “May events” in Paris broke through what Marcuse called “the memory repression of organized labor.” Rodney was fond of quoting Che Guevara’s advice that every activist should carry a serious book in their knapsack. In 1972 he published How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. He was assassinated in 1980.

At that writer’s conference in Montreal, Rodney called his presentation “History is a Weapon: African History in the Service of Black Liberation.” He began by exposing civilization—at least white man’s civilization—for the fraud that it was. He then contrasted its slavery and individualism with a true civilization whose characteristics could be found in African history before European slavery and colonization. It had three characteristics.

The first was hospitality. “I’m talking about a hospitable society, not the odd individual,” Rodney said.

The whole society is geared towards a reciprocal relationship with those around. And this, to me, is very very striking and it seems to me that, as a principle for human organization, it is one of the facets about African cultural development to which greater attention should be paid.

Such attention is finally being paid. His evidence came from European documents. Hospitality “was rooted in the nature of their social organization, for instance the family was an agency of social relief, and the principle scaled up to the clan, and then to whole social organization.”

A second characteristic was that members of African societies were always growing, always learning, until death.

And that is why field researchers have found that when you go into an African society you can go and find any old man. Find him, he might be sixty, he might be seventy, and with perspicacity he will point out to you elements of the culture and recall episodes of history going back more than a hundred years—in other words, more than his lifetime. Now this, to me, is tremendous. A society that takes you from birth and carries you all the way so that life has meaning to the end.

A third characteristic was self-rule by custom rather than by legislative statute. European travelers, Rodney said, wondered

How can we travel such huge distances from one end of the Empire of Mali to another and we don’t find any robbers, we don’t find any vagrants. If we lose something, when we turn up at the court of the king we find that thing has been transmitted there to be given to us.

Rodney’s reading was that “It was amazing to them because they were operating from the background of brigandage in Europe, highway robbery. I mean our society—well, capitalist society—is a robber society, so this explains the whole thing.” As for punishment for wrongdoing, in African society “it was a question of restitution rather than retribution being meted out to him. It meant that if he stole, the object was to replace what he stole, not to put him into jail. I have never ever read of a jail in traditional African society.”

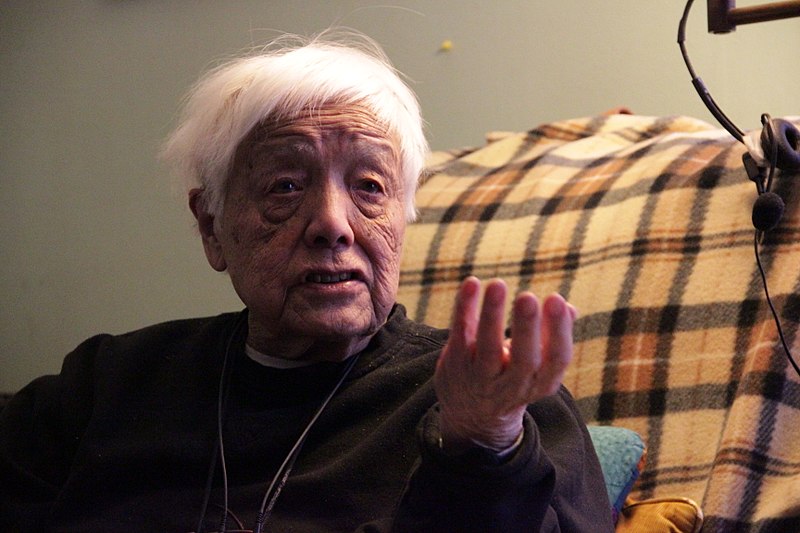

A month after Rodney delivered these remarks, Grace Lee Boggs spoke in Detroit on “The Black Revolution in America.” This was a revolutionary year in Detroit, in America, in the world, structured around the global division of labor of the auto industry. Black workers were in revolt. Grace Lee and her husband James helped define what that meant. As he wrote in Ebony in 1970,

A revolution involves, first of all, an escalating struggle for power, culminating in the forced displacement of the social groups or strata who have held economic and political power. . . . Secondly, a revolution involves the destruction of one form of social organization which has been developed to meet the needs of a given society.

Looking back on the past thirteen years, Grace Lee discerned “a movement involving ever deeper layers of the oppressed masses whose grievances are deeply rooted in the nature of the system,” “a relatively brief period in the lifetime of a revolution.” “In the course of the struggles for Black Power,” she concluded, “there are beginning to emerge the elements of a new vision of society in which all the institutions of twentieth century America are completely transformed.” Young blacks do not have “that Founding Father complex which characterizes the average white American.”

You boast of profit, rent, and interest—it seems like this great leap. This is the illusion of financialization.

As Boggs saw it, the white power structure aims at making a black middle class. The black youth of the cities recognize “that they have become expendable to a highly automated and cybernated society and that they will have to destroy this society or be destroyed by it.” She spoke of the Black Panthers, DRUM (Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement), and FRUM (Ford Revolutionary Union Movement) and the auto workers of Detroit who fought to control police, industry, housing, health. She was against the whole power structure and for elimination of the profit system and imperialism, “following in the footsteps of Malcolm.”

Grace Lee Boggs / Wikimedia

Boggs said that the United States is economically advanced but politically backward. The country was ripe for communism, having “essentially solved the problem of developing the productive forces.” We took up the slogan l’imagination prend le pouvoir. Afro-Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James wrote in his Notes on Dialectics (1948) that workers are preparing a “LEAP from objective conditions.” Four times on four separate lines he wrote,

LEAP

LEAP

LEAP

LEAP

James guided us to take those leaps in our own thinking.

This was also slave wisdom. Among Aesop’s fables is one that Erasmus, Hegel, and Marx all quoted. A boastful athlete brags in Rome about his great long jump on the island of Rhodes, a thousand miles away. A bystander challenges the braggart, hic Rhodus, hic salta—here is Rhodes, jump here! In Chapter 5 of Das Kapital Marx cites the challenge in the context of the riddle of surplus value, which seems to produce something from nothing. Yes, you boast of profit, rent, and interest—it seems like this great leap. This is the illusion of financialization. We must leave the sphere of circulation, where the exchange of equivalents is the rule and finance its most advanced form, to enter the sphere of the production. If surplus value seems to originate in nothing, then the people of the planet are nothing too, for it is they who produce everything. This is precisely what Walter Rodney and Grace Lee Boggs said over and over again.

In 1968 man had never leapt so high as he did in October, when Dick Fosbury set a world record in the high jump (7’4.5”) in the Mexico City Olympics. He leapt over the bar backwards, facing not terra firma but the heavens. This style of jumping became known as the Fosbury Flop. And it was not by man alone, for by amazing coincidence Debbie Brill of Canada had developed the same method at the same time, now called the Brill Bend.

I take the Fosbury Flop and Brill Bend as symbols for the year. They showed how the world would have to be turned upside down, what sort of leaps would have to be taken. But the Sixty-Eighters did not, in fact, turn the world upside down, and in that other sense too 1968 was a flop. The people of the southern half of the planet are poorer than ever, and those of the north richer.

A man does the Fosbury Flop. Jeromi Mikhael / Wikimedia

The world still needs turning upside down. First, in a social-political sense, by the abolition of classes and thanatocracy. Second, in a planetary-geographical sense, to restore the commons. We must restore the breach. Fifty years ago Martin Luther King, Jr., sought a means of doing this with a poor people’s campaign. This year it is being commemorated with a new campaign led by president of the North Carolina NAACP Reverend William J. Barber II, echoing the words of Isaiah in his mission to repair the breach and restore the streets to dwell in.