At a time when the president and leading Republicans are agitating to end birthright citizenship, it is worth reflecting upon the history of the Fourteenth Amendment, which enshrines this concept in our nation’s charter. Today the debate over citizenship is chiefly propelled by concerns about undocumented migrants. In the nineteenth century, Americans likewise had to decide what to do with migrants living among them, but the debate around birthright citizenship was principally driven by questions of what fate should befall the millions of enslaved people liberated by the Civil War, as well as their descendants. When the generation that fought the war decided upon birthright citizenship as the primary solution, it rejected white supremacy and brushed aside the fear articulated by Pennsylvania senator Edgar Cowan, an opponent of the Fourteenth Amendment, of being “overrun by another and a different race.” No people born in the United States, Americans decided, should be forced to live in the shadows.

No people born in the United States, Americans decided, should be forced to live in the shadows.

Historian Martha S. Jones’s central concern in her new book Birthright Citizens is not the legislative debates surrounding the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, often collectively called the Reconstruction Amendments for their role in establishing a post–Civil War legal order. Instead, she is interested in their prehistory during the antebellum period; specifically, she examines how free blacks made their mark on the broader question of political belonging by simply refusing to be treated as anything less than full citizens. They buttressed their actions with sophisticated legal arguments that these rights were already enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, Supreme Court decisions, and natural law. Jones’s scholarship depicts a model of alternative constitutional lawmaking through the generation of local norms.

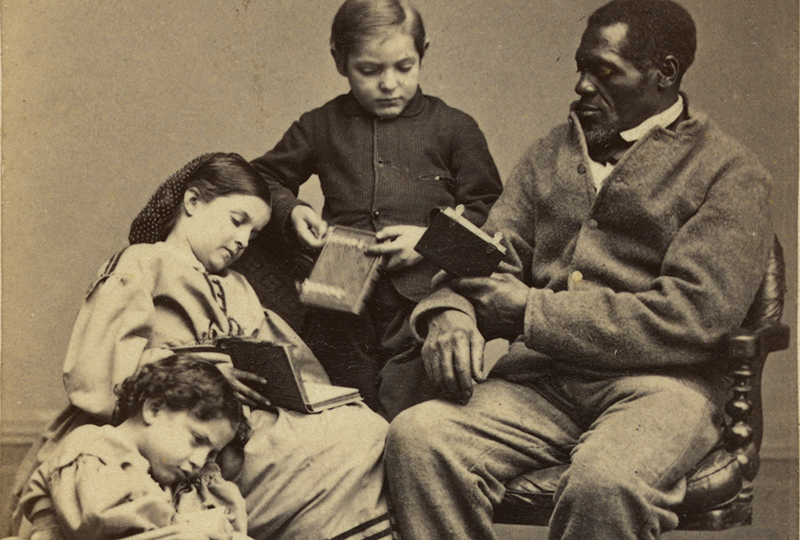

Though she toggles between national, regional, and state perspectives, Jones always returns to Baltimore to illustrate her argument. Weaving together court records and contemporaneous newspaper accounts, Jones convincingly demonstrates that free black people laid claim to U.S. citizenship by behaving like citizens rather than waiting for others to confer that status upon them. They made contracts, sued people, testified against whites in court, sought relief from debts, worshipped more or less as they wished, and exercised their right to bear arms. “Well before any judicial or legislative consensus granted their rights,” she writes, “free black men and women seized them.” What Jones sketches is an approach to reshaping constitutional norms that depends neither on a favorable national consensus nor on piling up electoral victories. Antebellum blacks traded on cultural notions of respectability and proved they were leading lives deserving of respect and recognition.

Unconventional methods of asserting one’s place within the political community were desperately needed because the nation’s founders made a contemptible pact with slavery. In 1790 18 percent of the U.S. population was enslaved; 94 percent of enslaved people lived in the South, where they were deemed by slaveholding elites to be indispensable to the region’s economy. The southern states would not have ratified the U.S. Constitution without some kind of terrible compromise over slavery. The institution’s name, abhorred by many freedom-loving Americans, would not be uttered in the nation’s charter; in exchange, states could count slaves as partial persons for purposes of representation; states could demand that other jurisdictions deliver up slaves who had escaped; and the federal government for the time being would not try to constrain slavery (though many states would). In the meantime, escalating political, philosophical, and literary resources were expended by slave-owning elites to justify slavery as a perpetual institution, even if working-class whites did not directly enjoy the fruits of an economy founded on slave labor.

That moral and political mess left the question of slavery—as well as cognate matters such as the legal status of emancipated slaves and their children—to be worked out at the state and local levels. During the antebellum period, inhabitants of slave states and free states led increasingly divergent lives, nursing dueling notions of citizenship and equality.

“Well before any judicial or legislative consensus granted their rights, free black men and women seized them.”

Jones’s bottom-up approach to the problem of black citizenship injects the agency of freed blacks themselves into the drama of the nation’s slavery debates and demonstrates that even in proslavery states, the matter of how they should be legally treated was messy and unevenly handled. Sometimes, this worked in the favor of free blacks. For instance, Jones proves that, despite a Maryland law that forbid blacks from testifying in court against whites, many Baltimore judges in fact admitted such evidence. Additionally, although blacks were prohibited by the state from gathering for religious purposes unless led by white clergy, Baltimore city officials construed this law to allow black churches to hold independent services simply by leave of the city or written permission from a white preacher. Permit requirements for black gun ownership were not always enforced in Baltimore, and courthouse records show that blacks regularly obtained gun licenses and filed the requisite paperwork containing the names of white men who vouched for them.

Reading Jones’s account, it is not hard to imagine that some knowledge of the lives led by freed persons must have later had an impact on legislative debates, especially when proponents of the Reconstruction Amendments denounced the horrendous local treatment of loyal, free blacks “born within the Republic.” John Bingham, often described as the Father of the Fourteenth Amendment, would later oppose the admission of Oregon to the Union, calling its first constitution—which barred every “free negro or mulatto” to “come, reside, or be within the state,” own property, or sue—“injustice and oppression incarnate.” That kind of outrage only has bite if listeners had some awareness, however imperfect, of law-abiding black people living in the United States and leading upright, morally rewarding lives.

But if former slaves and their descendants did their best to survive in the interstices of oppressive laws, Jones’s study also confirms the necessity of inscribing rights formally whenever opportunities to do so arise. Free blacks insisted on exercising the rights of citizenship as much as they could, but it is not always apparent whether this was possible because local whites believed in birthright citizenship—or instead merely because it was convenient at times to permit blacks to engage with state bureaucracy as though they were citizens. In short, because the rights of free persons were not explicitly guaranteed, they remained dependent upon white comforts, white economic needs, and white sensibilities. For instance, Maryland law barred free blacks who traveled outside of the state from returning, unless a travel permit was secured beforehand. Those who left the state without permission could be deemed “aliens.” Jones gives the example of Cornelius Thompson, a prominent black resident who was able to get a travel permit because he had friendly dealings with the state’s chief justice, Roger Brooke Taney. But untold black residents who lacked connections to powerful whites had to take their chances without a travel permit, returning clandestinely and at great risk. While some freed persons were able to live openly like white citizens—though always under the threat that one day everything could be taken from them at the whim of a white man—many more were unable to avail themselves of even these limited privileges afforded to their better-connected peers.

All too often, the power afforded white citizens to chaperone free blacks merely gave “rule of law” cover to new forms of state cruelty and private abuse.

All too often, the power afforded white citizens to chaperone free blacks merely gave “rule of law” cover to new forms of state cruelty and private abuse. Jones vividly discusses the plight of black children who were pressed to work for wealthier whites after they were declared by the state to be “orphans”—in some instances simply because their very-much-alive parents were destitute—or indentured by their parents as apprentices. In one case Jones details, when a black father objected to the indenture of his seven-year-old daughter to the mother of a police officer, the lawsuit apparently succeeded in reuniting parent and child. But mostly, such lawsuits appear to have failed, as black parents were outmaneuvered by profiteers with a more sophisticated understanding of the legal system.

One entrepreneur, an Irish immigrant named Michael Moan, bought and sold apprenticeship contracts. He once acquired the contract of a twelve-year-old black boy that required him to serve until he was twenty-four. But Moan went to Orphan’s Court, claimed that the boy had been stealing, and convinced a judge to extend the length of the contract, thereby increasing the value of the boy’s labor. With a judge’s blessing, he then sold that contract to someone else. On another occasion, Moan was sued for allegedly beating a young female apprentice. Moan went to a different judge, obtained a legal order that bound the girl to him, and got the original lawsuit dismissed.

Such cases reveal the limitations of a resistance strategy that rests on local laws and the politics of respectability. In the absence of codified fundamental rights, one’s fortunes could be upended at any moment; even one’s children could be taken away.

Jones rightly notes that because this strategy depended so much on white forbearance, its effectiveness was dramatically shaped by demographics. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the free black population in Baltimore swelled. Between 1790 and 1820, it “exploded” from 323 to 10,000. Other resources show that statewide, there were 107,398 slaves in 1820—more than a quarter of Maryland’s entire population—while free non-whites climbed to nearly 10 percent. Paradoxically, the emergence of a significant community of both free and enslaved blacks in Maryland created immense pressures in two directions: one toward greater social and political control of freed persons, and the other in favor of integrating freed persons into economic life and permitting them to engage in certain inoffensive forms of civic activity.

Without a guarantee of citizenship, former slaves and their descendants lived in a state of toleration. Yet social toleration is not the same as civic respect.

A rising concern among white citizens that they might be reduced to an incipient minority led to the enactment of exceedingly harsh measures to keep the free black population a manageable size and impose novel forms of social discipline. Maryland legislators drafted a new constitution in 1850 that outright banned abolitionism. The delegates’ report made the demographic rationale clear: “The free negro population, given the rate of progression, must in a few years, exceed the white population in eleven counties of the state.” As with foreign immigrants in our own time, freed persons were then portrayed as major threats to the local economy and culture. At the same time Maryland prohibited the migration of free blacks to the state.

Leading figures also tried to keep freed blacks lawfully residing within the jurisdiction in a state of ignorance, working around the clock for white employers, and away from what civic leaders considered the corrupting nature of abolitionist literature. As elsewhere, Maryland’s legislators fretted that the state would become a magnet for migrants, not only travelers from other parts of the United States, but also “free blacks and people of colour” from other parts of the world, especially the Caribbean. Others worried about the possibility of slave revolts aided by free blacks or abolitionists from other states.

Until birthright citizenship put an end to such pernicious proposals, the idea of removing all black people to such places as Liberia and Haiti enjoyed support from some surprising quarters. For their part, some freed persons believed they might be better treated in another country. Yet a number of white abolitionists reasoned that if the problem of racial anxiety could be eliminated by ensuring the wholesale relocation of black people to outside the country, then the major consequences of emancipation no longer had to be feared: no loss of political power due to the sudden addition of non-whites to the electorate, no interracial marriage, no dilution of Western culture. That might make ending slavery more feasible.

Ferdinando Fairfax, a Virginian who favored abolition, urged Congress in 1790 to create a black colony in Africa where emancipated slaves could escape white prejudice. Similarly, George St. Tucker opposed “banishment of the Negroes,” but he argued that after emancipation blacks should be subjected to “extensive legal debility” so they would choose to depart the United States of their own accord—a precursor to today’s conservatives who endorse “self-deportation” strategies against undocumented migrants. In the name of equality, and in the terminology of his time, Tucker favored a polite form of ethnic cleansing.

In short, while there is much to be learned from studying the strategies used by freed persons in Maryland to enjoy many of the benefits of citizenship and influence constitutional debate, Jones’s study also underscores the limits of this type of resistance. Without a guarantee of citizenship, former slaves and their descendants lived in a state of toleration. Yet social toleration is not the same as civic respect. Even on their best behavior, free blacks lived lives formally tethered to white patrons and employers. White bosses, lawyers, and judges in many respects simply stepped into the role of white slaveholders, exerting an outsized role in black lives.

Since the 1990s, a tiny minority has claimed that the Fourteenth Amendment does not apply to the children of unauthorized migrants. But that is not how its framers understood it.

Today we once again face questions about birthright citizenship. The modern analogues to the freed persons recounted by Jones are today’s migrants and refugees willing to serve as plaintiffs in lawsuits asserting their rights under the Constitution and international law, who pay their taxes and comply with the nation’s laws, and the Dreamers and other children of undocumented migrants who take to social media to humanize their plight.

Thanks to the Fourteenth Amendment, those born in the United States face a very different set of legal circumstances than the limbo that faced freed blacks prior to the Civil War. Generations of Americans have understood that amendment for what it says plainly: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

However, since the mid-1990s, a tiny minority has tried to dislodge this conventional understanding of the Citizenship Clause by claiming that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” excludes the children of unauthorized migrants born in the United States. But that is not how the Reconstruction generation talked about the issue. Instead, the historical record demonstrates that they envisioned the exclusion of only the children of foreign diplomats born in the United States and Native Americans, who were at the time still deemed to be members of foreign nations. For everyone else, including the children of Chinese parents then barred from becoming citizens and Gypsies in Pennsylvania, birthright citizenship was to be the rule.

A significant rupture in politics can certainly change what is plausible. After all, judges interpret the law against a field of politics and there is no telling what a Supreme Court dominated by conservatives will do if President Donald Trump proceeds with his plan to end birthright citizenship. If the Supreme Court ever confronts such a measure and once again endorses a Dred Scott–like category of non-citizens born on U.S. soil, the lesson of Jones’s book is that cultural resistance will be robust until conditions once again prove favorable to the restoration of birthright citizenship.