The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity

David Graeber and David Wengrow

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $35 (cloth)

The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux.

Then, some 10,000 years ago, humans began to farm, exchanging their gathering and hunting for domestication and permanent settlement. Communities grew denser and more complex, requiring strong leadership to manage resources effectively, and systems of writing to keep track of who produced what. This was a bad deal for farmers, who now had to work much longer hours in the fields than they had as hunters and foragers, but also produced a surplus of food that allowed other members of the community to specialize in new work, as craftspeople, priests, scribes, and accountants. Eventually, the first states emerged to coordinate the complex social arrangements that ensued and to defend their populations against other competitors. Ultimately those states became incorporated into the early empires of the ancient world, establishing humankind on the path towards the present day. From humanization, we get agriculture; from agriculture, we get science; through science, we get the modern world.

Let’s call this the Standard Narrative. It’s a very familiar story, and one that’s had quite a long time to develop. You may have encountered it in any number of places—a world history class in high school, a “Western Civ” course in college, or in one of any number of popular “big histories” of the human species written so far in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In this last category, we have works like Jacob Bronowski’s documentary The Ascent of Man, which first aired on the BBC in the 1970s; Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997), which also got the television treatment on American PBS in the early 2000s; and more recently, Yuval Noah Harari’s best-selling Sapiens (2014), which has been translated from its original Hebrew into an impressive sixty languages in addition to appearing as a graphic novel. And those are just the stories where the human narrative takes center stage. For the reader seeking an even larger historical canvas, there’s David Christian’s Origin Story: A Big History of Everything (2018), and the affiliated Big History Project, which leads students through nearly 14 billion years of history from the Big Bang to the present day—a process that takes, according to the Big History Project website, approximately six hours of self-directed study.

That these histories have been and continue to be incredibly popular almost goes without saying; according to its author’s website, Sapiens has sold more than sixteen million copies worldwide. Accessing these narratives of our species’ origins and subsequent social and political evolution has also never been easier. New discoveries from early human history are often in the news, the product of new technologies like ground-scanning “lidar” or the analysis of ancient DNA. Even some of the greatest hits of the Fertile Crescent civilizations circulate in contemporary popular culture. Delightfully, Ea-Nasir, the Sumerian merchant who saved the complaint tablets he received about his deliveries of sub-standard copper, has become a recurring Internet meme. But where do these treatments of the human story come from? What’s their history? And also—what happens if this popular and all-encompassing evolutionary narrative is wrong?

This is the opening premise of The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, by the late anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow. The product of a decade-long playful collaboration, The Dawn of Everything was to be the first of a series of at least four books, a wide-ranging synthesis that sought to be nothing short of a grand dialogue of human history. The manuscript was finished in August 2020, less than three weeks before David Graeber died, at the age of fifty-nine. This fact, and Graeber’s international reputation as a practitioner of both anarchy and anthropology, necessarily hangs over any attempt to review what ended up being his last book. As Wengrow remarks in the dedicatory foreword, Graeber was committed to living his ideas about social justice and liberation, to giving hope to the oppressed, and inspiring others to follow suit; this spirit permeates the book and its arguments. The Dawn of Everything is a fascinating, radical, and playful entry into a seemingly exhaustively well-trodden genre, the grand evolutionary history of humanity. It seeks nothing less than to completely upend the terms on which the Standard Narrative rests.

As they state in the introduction, Graeber and Wengrow didn’t originally set out to write a total history of humanity. The original question, which they first entertained in a 2018 piece published in Eurozine, was: “What are the origins of social inequality?” And yet, as they rapidly found, this frame seemed to unnecessarily limit the field of inquiry, leading to intellectual contortions like attempting to calculate Gini coefficients for Paleolithic settlements and letting Jean-Jacques Rousseau dictate the terms of intellectual engagement. Graeber and Wengrow instead ended up with two linked projects, which come together in this book. The first is to show that the Standard Narrative was the product of a conservative response to an Indigenous critique of European society and political inequality in the eighteenth century. The second is to consider the evidence for what Paleolithic humans and their descendants across the millennia have actually been doing, regardless of how well or poorly that evidence fits the terms the Standard Narrative has led us to expect.

The Standard Narrative is, in fact, significantly older than most twenty-first century readers suspect. Although expanded by archaeological and paleoanthropological research in the twentieth century, the original form of the Standard Narrative dates to the eighteenth century. The European colonial encounter with the New World—not only North and South America, but also Australia and the Pacific—created the conditions where European men of letters (and of politics) were confronted with evidence of entirely different ways humans had chosen to conduct their affairs. They were also confronted with enormously rich agricultural land, the prospect of lucrative trade in minerals, spices, and other raw materials, and the looming specter of another expansion-minded European power coming in and snatching the prize first.

Speculative arguments over the nature of rights, equality, and property may have been made in the salons and coffeehouses of Edinburgh and Paris, but these arguments were built on a foundation of evidence gathered overseas—and their application had very real and concrete consequences in violence, land expropriation, and other forms of dispossession for the people who already lived in the many societies found in these newly European-encountered worlds. It was in this context that the first arguments about the evolutionary progression of humankind through a series of universal stages of subsistence and social development—from hunting and gathering to pastoralism to agriculture and the administrative state—began to appear. These stadial arguments can be seen not only in the work of figures like Rousseau and Thomas Malthus (who disagreed on a great number of other things), but also in the work of economists, philosophers, and historians like Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant, and A. R. J. Turgot.

But these historiographical interventions—that the Standard Narrative is an Enlightenment inheritance whose motivations and origins bear closer examination—are only part of Graeber and Wengrow’s argument. Critically, they also argue that the creation of these stadial theories was the direct response not just to the European experience of New World cultures, but specifically to the European experience of a strong critique, coming from New World intellectuals and political leaders themselves—either directly, or transmitted through the medium of European commentators who were reporting back from New France on Indigenous ideas and laws governing generosity and material wealth, crime and punishment, and liberty and political power. The Dawn of Everything focuses particularly on the brilliant seventeenth-century Wendat (Huron) statesman and intellectual Kandiaronk, a frequent opponent and debating partner of the French governor in Montreal whose arguments and perspectives were preserved in a series of dialogues written by the (not particularly successful) French soldier Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, better known as Lahontan.

With this, Graeber and Wengrow make a frontal assault on decades of scholarship that has assumed that the Indigenous figures who appear in dialogues like Lahontan’s were entirely made up—either due to the many Classical rhetorical flourishes, which seem unlikely to have Algonkian or Iroquois or Wendat antecedents, or from an assumption of essential incommensurability between the representatives of two very different peoples and systems of government. But if we follow Graeber and Wengrow in taking Kandiaronk and his reception in Europe seriously, we can see how a set of ideas about liberty and the nature of freedom from a particular Indigenous thinker was translated and transposed into another set of arguments in the European Enlightenment, where, Graber and Wengrow argue, they joined ideas following a similar trans-Atlantic transit and sparked a conservative reaction so successful that it gave rise to a theory based on evolution through set stages of social and political development instead, which continues to this day.

This route is admittedly a long walk around to the Paleolithic, and well outside the normal topical ambit of most Standard Narrative works. But this argument is important—both to Graeber and Wengrow and to understanding their work. It allows us to connect the dots between twenty-first century criticism of, for example, the continuing emphasis on the idea of an agricultural revolution as a threshold in human development (because it fails to account for the multi-faceted food-gathering activities of a huge proportion of the world’s population and clearly did useful work in justifying colonial expropriation) and the actual conditions of Indigenous-European intellectual and political exchange and collision in the eighteenth century. But then, having established that the Standard Narrative of human development is perhaps not as grounded in objective fact as we might expect, Graeber and Wengrow embark on a tour of approximately 10,000 years of human history exploring new evidence that the record of human social and political behavior is also vastly more diverse and creative than we would think.

In their examination of “the protean possibilities of human politics,” Graeber and Wengrow follow the human story from the end of the Ice Age to the eighteenth century, from Africa and Eurasia to Oceania and the Americas. This is a vast temporal and geographical canvas, and the authors are quick to admit that most of this history is essentially unknowable. And yet, over the course of the past two centuries, practitioners of what we would now call archaeology and anthropology have gathered evidence of an astonishing range of human political and social practices. Much of this evidence, Graeber and Wengrow contend, contradicts both the received wisdom of the nineteenth and early twentieth century (that there is a set teleological path from hunting and gathering to agriculture to “civilization” and that traversing it was a positive evolutionary development) and more recent arguments—made, for example, by James C. Scott—that agriculture was often a mistake, but one that lots of societies got trapped in anyway.

What Graeber and Wengrow show, based on both recent and in some cases not-so-recent archaeological studies, is that human history is full of examples of wild experiments with different forms of social organization. There has never been a single path or a deterministic framework that conditioned how human history “ought” to go—nor has there seemingly ever been a social structure that didn’t ultimately, and sometimes rapidly, generate dissent and refusal. (If the reader takes one essential truth about humanity away from this book, it might be that we are, at heart, a species of Bartlebys, again and again declaring “I would prefer not to.”) Ritual and experimentation—or as the authors prefer to call it, “play”—have always played an enormous role in human affairs, whether in the invention of different kinds of political organization, in the creation of systems of food cultivation, or in the derivation of public, civic, and sometimes private property.

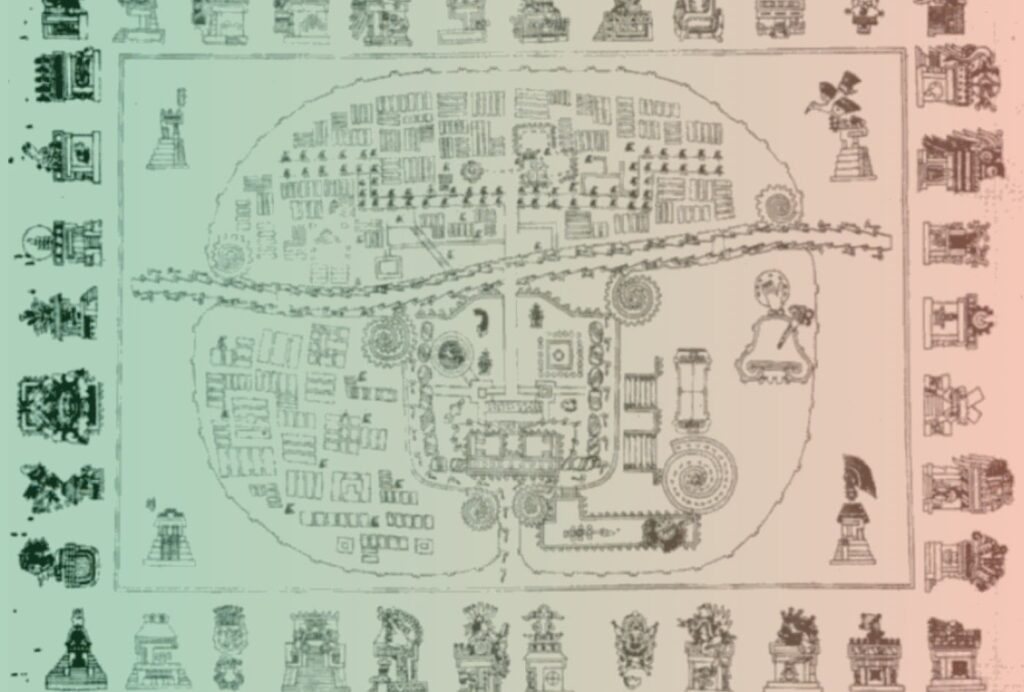

Shibboleths of high school world history textbooks fall left and right. Over the arc of the last 10,000 years, Graeber and Wengrow tell us, people have hunted or gathered in resource-rich environments; practiced occasional cultivation in alluvial regions; botanized and built gardens and orchards on small, individualized scales; or occasionally, in some fairly specific and unusual circumstances, grown grain and invested systems of writing to track and pay taxes with it. Plenty of communities appear to have tried farming for a bit and then opted out, with no apparent correlation to the size of their settlements or the authoritarian or egalitarian orientation of their system of government. Societies have arranged themselves in many different configurations based on concepts of neighborhoods or kinship or household or moiety—a social or ritual affiliation that divides a larger society into two sub-groupings—and extended these relationships across areas as small as a single valley or as large as a continental landmass. Organizing large groups of people often involved top-down authoritarian rule via kings or autocrats, but it didn’t always—and the fact that this mode of governance looms so very large in histories of the classic urban civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, for example, probably has more to do with the perspectives and political expectations of nineteenth-century British archaeologists than it does with the actual predominance of those forms over the long arc of Mesopotamian history.

The astute reader, of course, will notice how much hedging is in those last two paragraphs. As Graeber and Wengrow note up front, most of the span of human history is essentially unknowable. Even for those periods where some materials do exist, our evidentiary record is sparse. Some localities preserve better than others—an archaeological site in a desert or on a dry Mediterranean island or even at the edge of a glacial lake in the Alps has a better chance of preservation (and thus of thorough study) than one covered by tropical jungle or built on regularly flooded marshland.

Given this inscrutability of the past, though, what conclusions can we draw? On the one hand, Graeber and Wengrow ask, why should we act as if certain sites are paradigmatic when they might, in fact, be singular and strange? Why should the default be to assume a monarchical or authoritarian society? What sites, and whose cultures, have been and continue to be read as harbingers of modernity, “ahead of their time,” while others are written off as weird anomalies that can’t be fully understood? Why, for that matter, should leaving certain kinds of material traces be taken as the sign of civilizational success? On the other hand, a critic of Graeber and Wengrow might protest, if the material evidence of most of human history is inaccessible, the imaginative worlds of most of human history are even more so. Play, ritual, meaning—all these internal states fossilize poorly, or not at all. Graeber and Wengrow are working from a space of conjecture, conducting their own experiment in playful imagination. And yet, the book makes a strong case that these are experiments worth trying, if only because so many other, far less imaginative conjectures have dominated for so long.

Being in the business of deconstructing grand narratives, Graeber and Wengrow are uninterested in proffering an alternative grand narrative of their own. Although they’re critical of the contemporary human condition (and, in 2020 or 2021, who wouldn’t be?), The Dawn of Everything isn’t plotted as a story of humankind’s rise and decline. If we have gotten “stuck,” as Graeber and Wengrow write at both the start and the end of the book, the narrative impetus of this work is to provide us with a broader set of imaginative possibilities and to remind readers that social and political arrangements can be refused, reworked, reoriented, and re-done. All we have to do is walk away or start experimenting with the possibilities and see where that takes us. Demonstrably, as a species, we’ve done it plenty of times before.

It has to be admitted: The Dawn of Everything is not a particularly light or easy read. (It’s also quite a bit longer than most comparable works. Sapiens, which resembles a small brick in its mass market paperback form, is about two-thirds this length.) It is erudite, compelling, generative, and frequently remarkably funny, but despite the comparisons to the popular works of grand human history, it’s playing games in a very different genre. Frequently, Graeber and Wengrow’s arguments made me think more about recent works in science fiction, and not just because there are salient references to Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” On one hand, this is unsurprising—science fiction has long been the home of imaginative exercises in different social and political arrangements. On the other hand, it is perhaps depressing that the only other stories of alternate communitarian political arrangements that might immediately come to mind all feature far-future people living on spaceships.

One side effect of the Standard Narrative is that it comes with a fairly narrow political imagination. In the rush to explain how we got from there (anthropogenesis) to here (the triumph of man over nature, incipient ecological collapse, the ambiguous triumph of neoliberal capitalism, what have you), the range of historical possibilities is pruned away with each passing millennium until the only future that seems to have been possible is the one we’re in right now. This is partly an effect of scale: if you move the starting point back even further to the Big Bang (14 billion years), keeping open many possible futures becomes even more unmanageable. Even on a shorter timeline of just 3.85 million years (the emergence of Australopithecus afarensis), 2 million years (Homo erectus, Homo habilis) or 300,000 years (Homo sapiens), it’s understandable how a grand human history might trend toward a compilation of the species’ greatest hits. But, as Graeber and Wengrow would point out, the choices we make about what count as the major turning points in human development are not made in a vacuum; they privilege certain conceptions of history and who counts in it. Simply by dint of their form, these narratives tend to naturalize rather than defamiliarize the present state of the world. The Dawn of Everything, by contrast, wants to restore a sense of the contingent—to make clear how very unusual the homogeneously state-heavy configuration of the present world is.

The Dawn of Everything is also an outlier on another front. We have long moved on from the era where the accepted convention was to refer to “Paleolithic Man” as a universal-neutral term, but, as Alison Bashford pointed out in an essay in 2018, many people writing about the evolutionary history of the species continue to leave women out. In The Dawn of Everything, by contrast, gendered analysis runs throughout the entire book. As Graeber and Wengrow write, “women, their work, their concerns and innovations are at the core of this more accurate understanding of civilization.”

The earliest cultivation of plants was most likely performed by women; complex mathematics of the sort first recorded in cuneiform documents or given material form in complicated temple architecture seem likely to have derived and developed from “the solid geometry and applied calculus of weaving or beadwork.” “What until now has passed for ‘civilization,’” write Graeber and Wengrow, “might in fact be nothing more than a gendered appropriation—by men, etching their claims in stone—of some earlier system of knowledge that had women at its center.” Women participated in town councils and city assemblies alongside men in Mesopotamia’s Predynastic age, were memorialized in inscriptions as powerful rulers and spirit mediums in the final centuries of the Classic Maya period, and sometimes held enormous religious, political and economic power as dedicates of a god in the Third Intermediate and Late periods of Egypt. Certainly, these examples were not universal, and as Graeber and Wengrow note, the historical emergence of patriarchal power and the decline of women’s power within households and in society at large is undeniable. Why the power of women declined, however, is exactly the kind of question Graeber and Wengrow want to spur readers (and future researchers) to ask.

Given the radical nature of many of the book’s claims, it’s worth asking: How does the evidence hold up? Another reviewer has strongly criticized the book’s assertions about the differential experiences of settler and Indigenous captives in the eighteenth century, although that particular complaint doesn’t hold water. (Examining the relevant source, the issue hinges on an ambiguous line in the abstract, which was misread; evidence marshalled in the text itself, a dissertation from 1977, supports Graeber and Wengrow’s argument, although this seems to have sometimes required reading the evidence counter to the conclusions originally reached by the dissertation author himself.) Without going through every source in the book, I can’t say with certainty that the authors never overreach their claims, but in the areas where they directly touched on my scholarly interests, the surprises held up under subsequent investigation.

As Graeber and Wengrow write in the conclusion, they deliberately opted not to write in the traditional academic mode, where one lists all the available evidence and its interpretations and then makes a considered case for why one interpretation is to be preferred over another (or why they’ve all missed the point before proffering a new analysis). The challenge here is partly one of scope: given the conceptual, geographical, and temporal territory covered, Graeber and Wengrow would have ended up with an even longer book, and one that would probably leave readers with the sense “that the authors are engaged in a constant battle with demons who were in fact two inches tall.” They choose instead to synthesize first and critique second, and only when it is necessary to directly point out the flaws in the dominant narrative.

This reasoning is understandable, but also a source of occasional frustration. As a reader, I found myself wanting Graeber and Wengrow to name some names, to tell us exactly who came up with these tidbits of civilizational thinking and evolutionary theory that have so permeated contemporary thought and brought us so many restrictive conclusions. It would be interesting to see more cases where other analysts of the great historical arc of humanity have questioned the dominant story, other moments where the Standard Narrative came under strain. The teleological framework of stone tool development, for instance, began to crack in the 1930s under the combined forces of rudimentary systems of cross-regional geological dating (which established contemporaneity) and evidence that a much wider variety of stone tools had been made in many parts of the world. Of course, this might also explain why, in the Standard Narrative, the Paleolithic tool cultures get dropped into a vast “archaic” period (as Graeber and Wengrow describe in chapter three), where the dominant metaphors for human socio-cultural development are to baboons and other social primates, and the transformative threshold is shifted forward in time towards agricultural cultivation.

Certainly, making the arguments Graeber and Wengrow want to make often seems to have required reading against the historiographic grain or paying close attention to the work of people who have fallen out of fashion or were excluded from academic society all together. (On the flip side, Rousseau is at one point identified as “an otherwise not particularly successful eighteenth-century French musician.”) The sources cited are wide-ranging and sometimes older than one would expect—early twentieth-century anthropologists in the school of Franz Boas get a surprisingly good showing, mostly because they conducted exactly the kind of detailed ethnographic studies of Indigenous communities with diverse sociopolitical structures that the authors are most interested in.

And yet, once you start thinking like Graeber and Wengrow, it’s difficult to stop. For my own purposes, I recently returned to another collection of mid-twentieth century archaeological writing. “Courses Towards Urban Life: Archaeological Considerations of Some Cultural Alternates” was the title of a symposium held in Burg Wartenstein, Austria, in July 1960, funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research and organized by Robert J. Braidwood of the University of Chicago and Gordon R. Willey from Harvard. Braidwood and Willey were steeped in what Graeber and Wengrow would identify as the social evolutionary ethos, soon to reach its quantitative apogee at the “Man the Hunter” symposium held at the University of Chicago just a few years later. In organizing the symposium, Braidwood and Willey were interested in understanding what brought people to the “thresholds of urban civilization,” as they defined it—the “varying degrees of intensification” of food production, the transition from collecting food to producing it, and “the eventual emergence of city life and civilization.” Their framing of the symposium reflected their social evolutionary orientation, as did the interpretive conclusions they reached at the end of the week-long meeting.

Read the symposium discussion against the grain, though, and anomalies pop out—cases where the “threshold of cultivation” was apparently reached and then a society walked briskly away again, or where patterns of development appeared in unexpected places, following no discernible ecological or evolutionary rule. Some working definitions, like the established threshold for agriculture in Mesoamerica, were based on traits that could and frequently did appear completely independently of the social phenomena that they were believed to indicate. At other points, Braidwood and Willey admitted to having to fill large evidentiary gaps with post facto judgments and their best inferential guesses.

Over and over again, certain habits of thought seemed to appear that privileged certain arrangements of incipient states and power and sidelined others as oddities or failures, insignificant as data for building a grand theory of human development. One side of the scale was already tipped under the accumulated weight of political metaphors and heuristics inherited from the Enlightenment, refined in the high imperial decades of the nineteenth century, and reinforced and renewed by the mid-century social sciences. Braidwood, Willey, and the other participants of the symposium reached conclusions they felt were supported by their data and aligned with the dominant theoretical thrust of their moment. And yet, you have to wonder what other conclusions they might have reached had they tried another heuristic on for size.

The Standard Narrative isn’t going away any time soon. It has longevity on its side, and a storied intellectual history, not to mention continuing popular appeal, if those sixteen million copies of Sapiens sold in the last decade is any indication. But Graeber and Wengrow aren’t trying to out-compete or defeat the Standard Narrative—they’re experimenting and playing around with a different way of looking at the evidence and the history of humans and seeing what new configurations of social power and political ideals might result. In their narrative, there is no telos, no arrow of history. There is only humanity, creative and playful and violent and caring, imagining new social worlds and then going and trying them out.