Liberalism, it has frequently been said, is in crisis. In his recent book Liberalism Against Itself: Cold War Intellectuals and the Making of Our Times, historian Samuel Moyn attempts to explain why. The Cold War, he contends, pushed prominent liberal theorists in a new direction—one that continues to haunt politics today.

As part of our virtual event series co-hosted with The Philosopher, Becca Rothfeld, contributing editor at Boston Review and nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, recently sat down with Moyn to discuss his argument. (Rothfeld reviewed Moyn’s book for the Post in August.) Their conversation, moderated by Philosopher editor Anthony Morgan, ranges over Moyn’s portraits of Cold War liberals, cooperation and dialogue between liberals and the left, and whether it is possible to construct—or revive—an alternative to what Moyn sees as our Cold War liberal inheritance.

Below is a transcript of their conversation, which has been edited for concision and clarity. Learn more about our event series here, and find recordings of all our virtual events by subscribing to our YouTube account here.

Becca Rothfeld: The first question I wanted to ask is how to improve liberalism. Despite some misreadings of Liberalism Against Itself as illiberal, it’s very much not an anti-liberal book. It’s a book that’s disappointed with the direction that postwar liberalism has taken, but it’s also cautiously optimistic about the liberal tradition’s ability to redeem itself.

Tallying up your objections to Cold War liberalism in the book, I noticed that it was possible to construct a better ideal of postwar liberalism by imagining a sort of mirror image of the failed liberalism you describe. Could you say a little bit about the positive conception of liberalism glinting in the background of the book?

Samuel Moyn: This book is a series of portraits of liberals in the middle of the twentieth century, and I take a pretty deflationary view of the politics that they wrought. I claim that they introduced a rupture in the history of liberalism. I do imply that they’ve left us, at least in part, in our current situation, intellectually and even practically. I don’t know if I would agree that I’m optimistic about liberalism: I would say that there are resources from the past to draw on before Cold War liberalism that could be used to argue for a new liberalism. But I certainly think that we need to give tough love to liberals, not just for their abuse of their own tradition, but also because they seem recurrently incapable of confronting some nagging criticisms of their platform.

You’re right that I do suggest (albeit indirectly) some laudatory features of liberalism before it became transmogrified through the Cold War liberals. I’ll mention a few. The first half of the book is about what liberalism was before Cold War liberals abandoned its core motivation—human emancipation. I start out with a chapter on the Enlightenment that defines the epoch through its promotion of emancipation from the ruins of authority and tradition. But a much bigger component of Liberalism Against Itself is the contrast I draw between the self-perfectionism of the Enlightenment and the tolerationism that surged through the careers of more recent liberals like John Rawls. In the beginning, liberals were total perfectionists. They offered a novel, controversial ideal of the highest life, one premised on personal fulfillment through creativity. That’s because the early liberal thinkers were also romantics, were deeply connected to the Romantic movement in literature and philosophy.

Another component of early liberalism that should be resuscitated is an ethos of progress. Liberals before the middle of the twentieth century were connected to a sense that history was a forum to achieve emancipation and to construct interesting lives. Agency doesn’t just materialize—the conditions for it must be built. To the early liberals, those conditions aren’t going to appear overnight. There were a lot of reasons in the middle of the twentieth century to give up on progress—certainly the notion of inevitable progress. What I worry about is an overcorrection: that Cold War liberals lost any sense of an uplifting, radiant future to offer through policy, both locally and globally. A truly emancipatory vision for liberalism would involve reversing some of the damage of that pessimistic thinking.

BR: Liberalism Against Itself is very concerned with canonization and how rewriting the canon specifically is a big part of the Cold War’s impact. I was wondering how you might rewrite the canon today. What figures from the tradition would you reintroduce?

SM: I would put back those who got expunged by the Cold War. I agree with Harvard thinker Judith Shklar that Cold War liberals expunged the Enlightenment from their canon. They saw it as the source of totalitarianism. We agree that this was a disastrous mistake.

The Romantic movement was also central for all the early liberals—Benjamin Constant, Alexis de Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill—all of said that that liberalism was about creating the conditions for living interesting lives. I wouldn’t say Hegel was a liberal, but liberals certainly became Hegelians in their intellectual premises. And toward the end of the 19th century liberals became, if you like, liberal Marxists. They learned from Karl Marx about their own mistakes in adopting laissez-faire economics. That realization is why we got the welfare state. I don’t think John Rawls is doing something that’s thinkable but for the late-nineteenth century new liberalism.

Along with all these other movements that get expunged during the Cold War, we have to go back to the French Revolution, which was the birth of political emancipation in modern times. Liberalism began as a continental phenomenon, not as an Anglophone phenomenon. The American Revolution, for instance, was not on par with the French Revolution. In the Cold War, the terms were reversed. The American Revolution, in the work of figures like Hannah Arendt, was made the font of a more libertarian freedom. The French Revolution was represented as the source of terrorism and totalitarianism. But the French Revolution deserves to be in the liberal canon, as a fulcrum between the Enlightenment, Romanticism, and Hegel’s attempt to blend them.

BR: What about the utopian socialists?

SM: Liberals helped invent socialism. Bernie wasn’t the first liberal socialist. We should hold a place of honor in the tradition of liberalism for socialism.

BR: I think Rawls is a democratic socialist, but that’s a conversation for another time.

SM: Fair enough.

BR: You claim in your book that Cold War liberals reject the Enlightenment. I felt that was a striking claim because some of liberalism’s loudest opponents—Patrick Deneen, a reactionary communitarian, for example—are fond of accusing liberalism of being steeped in Enlightenment thinking. I was wondering whether there are certain aspects of the Enlightenment that you’re emphasizing, certain aspects of the Enlightenment that the Cold War liberals dispense with. The Enlightenment is a capacious tradition, so there’s space for you to say that there are indeed some aspects they jettison, and some they keep.

SM: In her early work, Shklar worked with a definition of the Enlightenment as the emancipation of human agency from authority and tradition. I’m for that reading. Whether those ideals were actually at the core of Enlightenment thought is secondary because, when we canonize, we also pick and choose and winnow.

Scholars today might say there was no Enlightenment; there were multiple enlightenments. Shklar herself, as she became more of a Cold War liberal figure, associated the Enlightenment not with emancipation but with skepticism. So obviously, in any of these inventions of liberalism, we’re also going to be, in a sense, inventing our own lineage in the past. I’m for thinking about intellectual history as also a political act of finding what we want in the future in our past. Luckily, the Enlightenment provides a resource for that view of modernity as about human emancipation.

There are other views, from both Enlightenment-phobes and Enlightenment enthusiasts. Take Stephen Pinker, a later Harvard professor, who should be treated with caution for the way he associates the Enlightenment with a conflict between reason and religion or scientism versus positivism. That’s not what I want to rescue, although it’s only fair to note that there’s going to be some connection between the emancipation of agency and, say, natural science and what it has done for human beings in the world in the last couple hundred years.

BR: Pinker was someone that I had in mind as a kind of cautionary tale for adopting a triumphalist conception of liberalism. I was wondering how we could be optimistic and emphasize progress without becoming triumphalist in the way that Stephen Pinker is. Pinker is someone who celebrates modernity as a great achievement while underemphasizing the things that were bad about it. How do we avoid that pitfall if we want to bring a focus on progress back into liberalism?

SM: Stephen Pinker is a really interesting person to think with, because he is a progressivist liberal who is downright celebratory about modern times. And we need to look carefully at the basis of his giddiness: it turns out that it’s almost biopolitical. The criterion that he uses to measure progress is not a full-fledged sense of emancipation but questions like, Do you live or die? Do you survive past a certain age? Is there violence? How much is there? What’s the murder rate? Those questions aren’t trivial by any means, but they’re cramped. When we think about freedom, of whether we’ve created the conditions for distinctive personalities in a relatively conformist age of consumer capitalism, we begin to see that Pinker has left a lot out, and has not seen the way liberals have allied themselves with the forces of the market—which may have had salutary effects but also had a dark side.

I’m suggesting that we need to have a story about freedom, the kind that Hegel had. And we can imagine a future of universal emancipation, but we can’t get ahead of ourselves. The Cold Warriors weren’t only trying to provide cautionary notes against giddy Enlightenment enthusiasts. They rejected the Enlightenment and progress out of fear that the Soviets, their enemies, had taken ownership of them. They went further than course correction to reinvent liberalism as a tragic creed of those who should abandon hope and give up emancipation as an ambitious political project.

BR: Do you think that Cold War liberalism has any redeeming features? It seems like you do think that history is to some extent teleological, and that there’s many respects in which modernity is better, hopefully not just with respect to the death rate and child mortality and the like.

SM: I wanted to be empathetic to it. The second chapter of my book is about one of the most famous Cold War liberals, Isaiah Berlin. The chapter is pretty upbeat because because it shows that against essentially all the other Cold War liberals who denounced romanticism as a font of totalitarianism, he wanted to rescue it, and with it, the moral core of a perfectionist liberalism.

I would also add that one can only empathize with those who experienced the rise of National Socialism and the early years of the Cold War’s nuclearized standoff. These were indeed very scary, and made it very difficult to believe in progress. And yet I wonder if they overcorrected. So my book is polemical: it’s about the Cold War liberals’ unintended consequences of so overcorrecting in their reinvention of liberalism that they might themselves have been appalled. It’s not a polemic in the sense of indicting them as human beings; it’s about the worth of their thought. And we should have tough love for those in whose tradition we find ourselves in today. We should ask what led to this crisis with people like Patrick Deneen declaring the definitive failure of liberalism and Donald Trump looming once again as the possible president in 2024.

BR: I wanted to ask you a little bit more about Isaiah Berlin because I also read him as a perfectionist. But I also read him as a good model for how liberals could better go about their perfectionism, because he seems to think that a pluralistic form of life is a good form of life. Martha Nussbaum has a paper where she describes Isaiah Berlin and philosopher Joseph Raz as both pluralists and perfectionists in contrast to Rawls, who she sees as an antiperfectionist liberal. I wonder if you think Berlin is a promising model for a perfectionist liberalism going forward.

SM: What strikes me about Berlin is first his contribution to the analytical distinction of forms of liberty. It’s fairly clear that his intent was to write a Cold War tract, distinguishing the West from the Communist rest for hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of readers. Berlin provided an optimistic answer as to why the United States was involved in the Cold War. His answer was a libertarian conception of freedom against positive freedom understood through self-realization in a perfectionist mode.

But it’s also true that at the same time, in his loving reconstruction of the significance of Romanticism as leaving us in a situation of inevitable self-making, Berlin struggled with libertarianism. This comes out most clearly in an essay called “John Stuart Mill and the Ends of Life,” where he portrays Mill as in the situation he himself was most devoted to: a perfectionist sense of what would make liberalism worth having that was also oriented to a fear of the state harming individuals. Therefore, Berlin wasn’t necessarily thinking about the kind of institutional conditions—like state action—that might be required to create a society that could promote broad-based perfectionist self-making.

As he aged Berlin began to speak a lot more about pluralism, which he understood with a tolerationist spirit—there are various groups in society with incompatible goals that don’t easily square with one another. I think the roots of any healthy pluralism, one defined by the pursuit of individual emancipation, were obscured by his later career, though. He loses a theory of pluralism of individual perfection, asking only, How do we promote mutual coexistence between groups with different ideologies and approaches? That kind of theory brings us very close to the later Rawls. Unfortunately, both of these figures—the later Berlin and the later Rawls—lost cognizance of the kind of individual or group identity that would be worth defending philosophically, one rooted in freedom and self-making.

BR: I think that’s right: there’s also lots of different Berlins and so you can sort of find him in a more celebratory mood or like a less celebratory mood. Next, I have a question about Lionel Trilling. Trilling is a postwar literary critic who was pessimistic, and he cautioned his fellow liberals to be more realistic about human nature. He was also into Freud. In the book you criticize Trilling for his pessimistic politics. Is Trilling is genuinely invested in politics per se or should his claims about liberalism be read as an argument about interpersonal ethics, or even aesthetics? Trilling talks a lot about liberal novels, for example. There, he’s not calling for a different political platform but for fewer black-and-white fictions. A lot of the stuff he’s talking about is authors that he likes because they have complex characters, like E.M. Forster. I wondered what you thought about this.

SM: Trilling is such a rich figure, and I detected in him an ambivalence to the construction of a Cold War liberalism. He understood that liberalism, as he theorized it, was about the person and their need for self-regulation. Trilling’s liberalism, to me, comes from the trauma he experienced in the 1930s, which he never overcame. But in his own account his politics come from his discovery of Sigmund Freud, and especially Freud’s account of the death drive. To me there’s no way of distinguishing someone like Trilling who is insisting on a new kind of liberal self, one very controlled and self-regulating, and liberal politics generally. Trilling believed, unlike Berlin, that politics is rooted not just in whether the state is interfering with individual choice, but how the individual is put together.

Trilling overreacted to his own ideological experience his sense that progressive liberals were innocent and naive, unschooled in the reality of death and the death drive and thus likely to play into the hands of liberalism’s enemies. He constantly wavers on the brink of renouncing his self-denying liberalism, especially in his sole novel The Middle of the Journey. To use a Freudian category, Trilling is a melancholic who never moves to mourning, who can never overcome his longing for the kind of Romantic liberalism he’s insisting that everyone now renounce.

BR: Liberalism Against Itself is a history book, but it has many resonances with the contemporary political situation. It seems like every day there’s a eulogy to liberalism or another piece about how liberalism has fallen out of favor. Patrick Deneen’s book is called Why Liberalism Failed, as if liberalism’s failure isn’t even a debatable question. You write that Cold War liberalism styled itself as a series of “defenses in an emergency,” which seems true of liberalism today, particularly in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency. I wondered if you could talk about the book’s resonances with our current situation. Do you think that liberalism is not popular now because it’s not making a good case for itself? How can we save liberalism from Patrick Deneen and his ilk?

SM: I feel like this is not a new situation. It’s true that in the past, liberalism didn’t have as many enemies inside the gates as was revealed on January 6. But my whole life has been under the regime of the reassertion of Cold War liberalism. I think that is especially true after 1989, when liberals didn’t take the opportunity to make their ideology credible enough to be durable. One of the main reasons for this is that Cold War liberalism is, in many ways, a precursor to neoliberalism. And to this date, liberals haven’t repudiated neoliberalism strongly enough. In our time, after the War on Terror, a state of emergency where the United States faced overseas enemies, you find a lot of liberals taking the same attitude about an almost elemental need to preserve freedom against its enemies—whether they are postmodern professors, woke young people, or Donald Trump’s voters.

Through all of that history, Cold War liberalism has done two things. It’s helped us scapegoat a lot of people, and not face the need to reinvent liberalism, to return it to some of its optimism from the past and pivot to a future where it could be appealing, in boring terms, to enough voters to survive some of these decisive elections when we think liberalism itself is on the line. If we just scold people for not understanding how a very minimal liberalism is worth retaining, we’ll have missed the opportunity to offer them something worth embracing. Liberalism can’t be minimalist anymore. It must take on board its older resources and renovate itself in completely different ways than any early liberals allowed. So it’s not as if going back to the future just means exhuming some earlier version of liberalism: I’m just suggesting that there are resources there if liberals want to be a credible source of appeal in an ideologically contentious world that’s no longer at the end of history.

BR: At the beginning of the Obama presidency, it seemed for a moment like there was an air of optimism, but then it became neoliberal business as usual.

SM: The enthusiasm of that moment, the emotion that many experienced, is worth remembering, because it’s almost impossible to have that kind of stance toward politics now. The investment that a lot of people, especially young people, had in politics got crushed because, when it came to economics and foreign policy, Obama didn’t break with what he’d inherited. The consequences of this have been very grave for liberalism itself.

BR: Even though Biden is leftist in certain ways, he’s not articulating a rousing vision for progressive politics or liberalism.

Anthony Morgan: I want to start with some more specific questions about Samuel’s theme of Cold War liberalism. First, could you explain more about what in liberalism was rejected after the Cold War and what its political consequences were?

SM: After the Cold War? I would say not a lot was rejected from the Cold War liberal period. It’s only fair to note there were the 1960s and the New Left who named the Cold War liberals—those are the dissidents to whom we owe the phrase “Cold War liberalism.” But in the 1970s and ’80s, especially in the cold climate of the defeat of George McGovern’s campaign and the victory of Ronald Reagan, a certain wisdom crystallized that we had to adopt to Cold War liberal precepts, to meet the Republicans halfway by adopting neoliberalism in the Democratic Party. Nothing changed after 1989. Liberals doubled down on their libertarian turn in the later Cold War. I have argued that the same is true for American militarism. After the Vietnam War and the failed McGovern candidacy, liberals learned to be forceful as a condition of winning. But down through Barack Obama, they never took seriously the illiberal consequences of American geopolitical leadership—and after 1989, that became very graphic in ways we’re still processing.

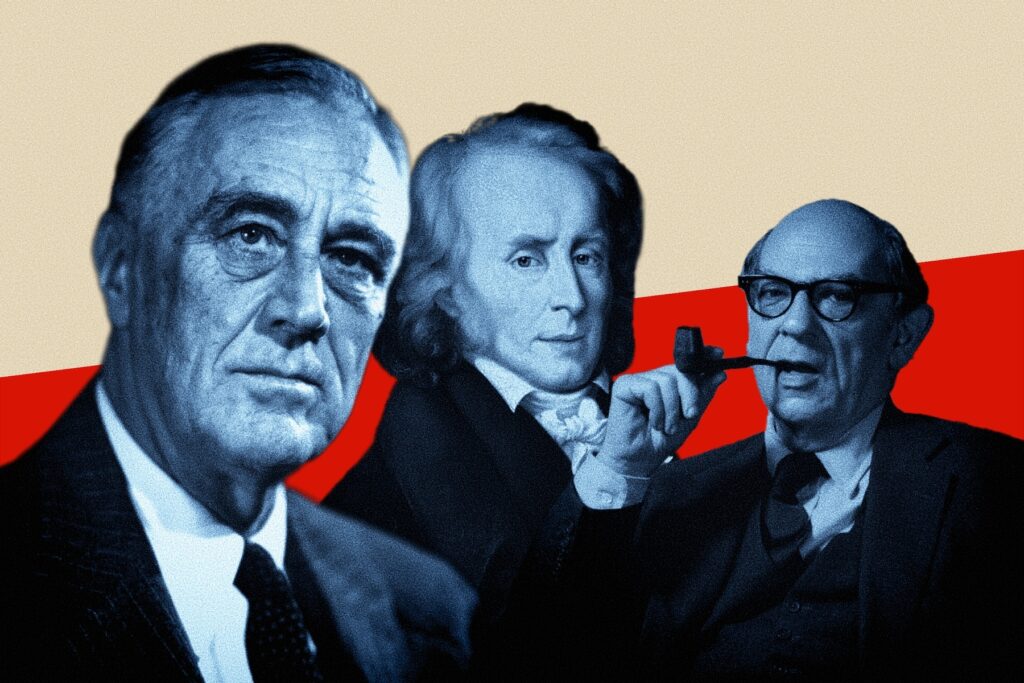

AM: Next is a question from an audience member. What role did Roosevelt and his Four Freedoms play in the development of postwar liberalism?

SM: Roosevelt tried to think of himself as enacting the “new liberalism,” a socially conscious, welfarist liberalism. And of course, he said that “the only thing to fear is fear itself.” Yet later, Cold War liberals reoriented liberalism around the elemental experience of fear: fear, in particular, of the Soviet Union.

It’s important to note that for a while, this established a mismatch where Cold War liberal thinkers were radically transforming liberal theory while in practice, liberals were building redistributive welfare states—the biggest, most interventionist, most egalitarian ones they had ever built. But if you read “Two Concepts of Liberty” by Isaiah Berlin you would have no idea that liberals were doing this in practice. And this mismatch just couldn’t be sustained. And though Rawls would remedy this on the theoretical side, it only created a new situation where liberal theory was completely out of sync with the practical victory of neoliberalism’s hollowing out of the welfare state.

So I want to credit Roosevelt as being sort of the last new liberal who dies before he can save America from the coming of Cold War liberalism. And while he has some heirs through the Great Society, ultimately his practical program has no ideological support, especially at the heights of liberal theory, until John Rawls. But at that point, the practical energy to realize it had evaporated.

BR: There’s now a cottage industry of left-liberal Rawlsians who dominate political philosophy, a huge intellectual tradition justifying FDR-style liberalism, but it’s too little, too late. I love Rawls, but I don’t see much of his intellectual tradition being realized in politics.

SM: I think there’s very important work from Katrina Forrester and others that tries to think critically about what it was about the form and style of Rawls’s thought, and also the substance—because he took a lot from Cold War liberalism—that relegated him to this mismatch situation where the world moves away from him as a result of him finally publishing his masterwork. Whether he was a socialist remains an open question: there is a case for Rawls being a socialist but there’s also a case that he wasn’t.

BR: It’s not like we could just enact a theory of justice anyway. Rawls operates at a level of theoretical abstraction; his work is not exactly like a blueprint.

SM: Yet it’s worth noting that a lot of constitutional theorists have tried to find forms of constitutional law that could translate Rawls’s abstract principles into more workable precepts.

AM: Another audience question asks, Are there lessons to be learned from the Cold War liberals for progressives working outside of the liberal tradition, in movements like ecosocialism, the Green New Deal, abolitionist movements, or Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions?

SM: Absolutely. The liberals of the kind I’m calling for would be allies for leftists. We’re familiar, because of the Cold War, with the idea that there is an unbridgeable gap between liberals and the left. But I think that’s anachronistic: in the later nineteenth century, the left proved to be a productive element in the reinvention of liberalism. That’s why I use the phrase “liberal Marxism” to describe the work that was done. In the United States, the entire progressive campaign against laissez-faire economics can be interpreted along the lines of what Marxists were saying in Europe about purely formal freedom that doesn’t lay the foundations for a society in which the conditions for freedom exist and make freedom credible. So philosophically and strategically, there’s no reason to think that liberals and the left can’t establish a mutually supportive relationship. That doesn’t mean there won’t be bickering and there won’t be lines to be drawn, but those will be less and less important as time goes on—especially to the extent there is a powerful new right and the center begins to fail even more visibly than it has already done. At that point, solidarity across the left spectrum will be essential.

BR: The Cold War liberals are also just worth reading because they’re smart, and they’re good writers. Even when they’re wrong about things, they’re important figures to learn from. In particular, Berlin, in his more celebratory passages about pluralism, articulates what could be developed into a perfectionist liberalism that is more obviously sympathetic to leftism. And Trilling is just a great prose stylist.

AM: Next are some more general questions. Which are the main kinds of freedom that liberal thinkers focus on and how do they come into conflict? I’m thinking of how liberal ideas of economic freedom undercut other kinds of freedom, for instance.

SM: One of the revolutions in our understanding of liberalism is the refusal to begin the story with John Locke, a thinker who was only understood as a liberal in the twentieth century. Locke focused on a more libertarian sense of pre-political rights, especially on property as the basis for government. The first self-styled liberals only came about in the 1820s, in continental Europe. Most people don’t know that there weren’t large numbers of American self-styled liberals until after World War I, with the founding of The New Republic magazine. The first American liberals, those associated with The New Republic, were not economic liberals. There’s no reason to believe that one should associate free self-creation of the kind that the early perfectionist liberals championed with laissez-faire economics.

It’s true that these liberals often thought of laissez-faire, overly optimistically, as a tool of emancipation, because it did make people transacting in marketplaces equal despite their different faith traditions or even, at times, gender and race. That was enormously liberatory. But Mill is a great example of someone who understood that that the market wasn’t just a tool for emancipation but a recipe for oppression.

We live in an ideological world where Berlin’s portrait of liberty as freedom from state interference could be easily mistaken for neoliberal—and did help bolster the ideological conditions in which it was plausible to have a liberalism that was about economic freedom against state intrusion, interference, taxation. But I still think we can make the relevant distinctions and return to a liberalism that is concerned with economic freedom to the extent it’s useful for abundance and growth and liberation and challenges it when it leads instead to class hierarchy and oppression.

BR: Kant is arguably one of the first liberals, and he has a much more extensive understanding of freedom as self-determination or compliance with laws one set for themself. People like John Stuart Mill and even the later existentialists also understand liberalism as creative self-determination. A lot of left liberals, though, are less interested in freedom than they are in justice, which they understand as a matter of distributive equality. Rawls, for example, cares about civil liberties a great deal. He thinks there should be a Bill of Rights ensuring freedom of speech and the like. But his primary concern is how resources should be distributed so that people get equal portions. He doesn’t necessarily see liberties and distributive justice as opposed, although he does think that liberties are prior to the distribution of resources.

AM: Another question asks, Do you see Black radical liberalism, such as the kind articulated by Charles Mills, as a promising route to reinvigorating liberalism?

SM: None of the resources in liberalism prior to the Cold War equip us to face the profound gendering and racialization of liberalism, even today. For that matter, the global politics of the liberals before the Cold War were often straightforwardly imperialistic. I have no nostalgia at all for these facets of liberalism. Mills is amazing because he indicted the racialization of the liberal theory in the past, but in order to save liberalism. He really did embrace liberalism as a model—very controversially—toward the end of his life. I’m a humble disciple of his. Mills seems to me a really appropriate model for someone who understands that we needn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, but also doesn’t understate the genuine challenges that liberalism is going to have to face forthrightly if it’s going to make itself credible.

The years since the Trump administration have been incredibly disappointing in this regard. The Cold War liberal approach has focused solely on extinguishing the enemies of liberalism. That’s not what Charles Mills taught—he understood that liberals need to clean their own house if they’re going to be a credible ideological source in our time.

BR: I agree. Left-liberal theory, which I think is the most promising intellectual tradition that we have currently for moving liberalism forward, is very abstract. Most of it is ideal theory—which is to say that it’s totally unconcerned with implementation. That’s theoretically useful, but I do think that critiques from Mills and feminist critiques from people like Susan Moller Okin can help us if we want to actually implement some of the more abstract principles that you find in thinkers like Rawls.

AM: One last question: What would be lost if liberalism was lost?

SM: It really depends. Liberalism stands for some important values, but we could imagine a world in which those values are reclaimed by another tradition with another label. In that case, very little would be lost, especially given all of liberalism’s flaws. But if we take Patrick Deneen’s views seriously, we have to say that everything is at stake in the endurance of liberalism because it stands for what we all care about: the possibility of living beyond authority and tradition and making the meaning of our life ourselves—not according to the dictates of someone else. I think everyone has a stake in self-determination, and liberalism, ultimately, is a great purveyor of that ideal. That’s what makes its dire straits today so sad.

BR: I think that’s right. At its best liberalism establishes the conditions for pluralism and celebrates difference. While we can imagine that being captured under a leftist regime, I think that’s something in liberalism that’s worth preserving.

Boston Review is nonprofit and paywall-free. To support work like this, and keep our website open for all to read, please donate here.