In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s jolting Electoral College victory, a moment of peril for liberals and leftists alike, both groups would do well to grapple with the true histories of these traditions, which have become mere caricatures for too many Americans. Progressives ought to forsake the half-truth that liberals and leftists always work at cross-purposes; they should recognize the long, if obscure and complicated, history of liberal-left cooperation in American history. The still widespread picture of liberal reform and leftist radicalism as intrinsically antagonistic is an historical product of the Cold War.

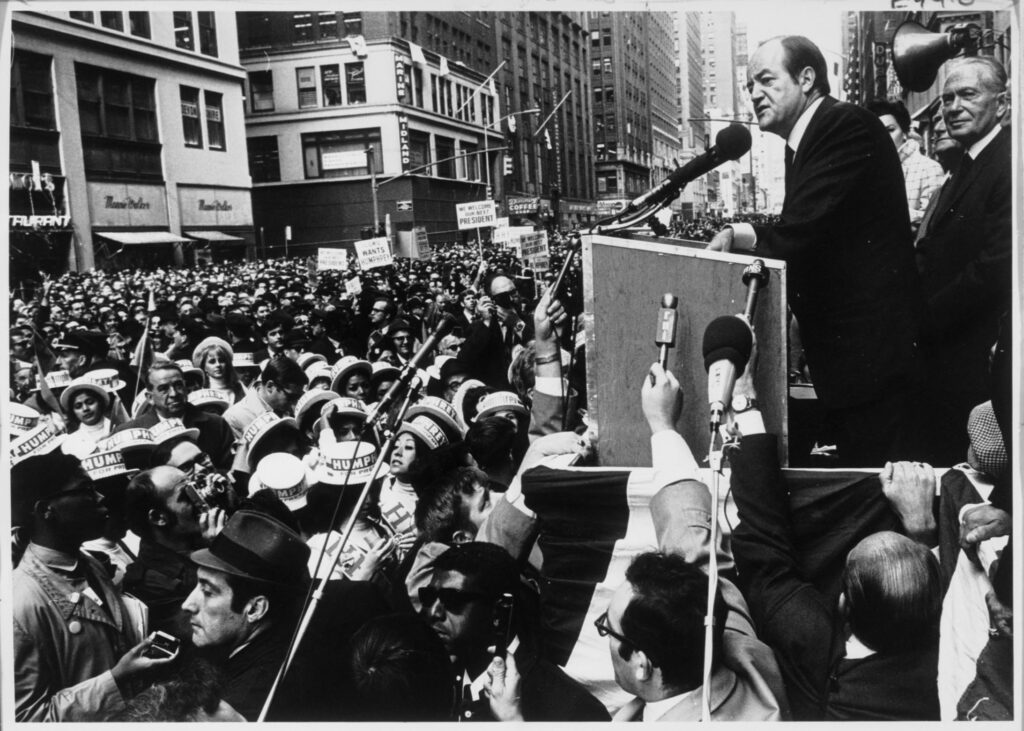

In the late 1940s and 1950s, liberals—mainly Democrats—spurned and helped to repress leftists, who were tarred with the brush of Communist sedition. This had started well before Joseph McCarthy got in on the act. Visiting the United States in 1947, Simone de Beauvoir lamented that “the ‘red terror’ is growing; every man on the Left is accused of being a communist, and every communist is a traitor.” Liberal Democrats, who found themselves besieged by Republican accusations of having coddled the Communists, decided that the best defense was a good offense—against the left. Hubert Humphrey went so far as to call Communists “a political cancer in our society,” a metaphor that demanded harsh medicine. Though he did not wish to treat all leftists in such a punitive manner, the entire left was drawn into a vortex of anti-subversive mania.

The widespread picture of liberal reform and leftist radicalism as intrinsically antagonistic is an historical product of the Cold War.

After this red scare ebbed, a New Left arose among college-educated youth in the sixties, and they generally saw liberals as members of a hostile establishment, not as potential partners in a broad progressive front. Still, some did entertain hopes for a political realignment. In this scenario reactionary white Southerners would flee the Democratic Party, making way for a powerful social democratic organization. (Half of this prophecy did come to pass.) That dream withered rapidly after liberal Democrats, led by John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, escalated the Vietnam War, an act which confirmed to many that liberals and leftists had nothing in common. Some radicals supported the antiwar presidential bids of Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy in 1968, but most avowed leftists disdained these men, and they roundly scorned Humphrey, the compleat Cold War liberal who became the Democratic standard-bearer. Since it could find no home with opposition Republicans, peace activism primarily took the form of anti-systemic protest, shunning both parties.

These sharp images continue to shape our thinking about left-liberal relations in American politics. The World War II and Baby Boomer generations came to see these political entities as inherently discordant. Yet many today lament that, in theory, liberals and leftists ought to work for broad, common goals; otherwise no one would think that Ralph Nader’s voters in 2000, or Jill Stein’s in 2016, should have voted for the Democrat. We seem caught between obsolete models of progressive politics and a yearning for a progressive solidarity that is closer to fulfillment than we may realize. A deeper look at the histories of liberalism and the left in twentieth-century America shows a fluid relationship, often troubled but not always adversarial. Now—with the election of Trump, the defeat of the Democrats, and the democratic socialist challenge from Bernie Sanders and his supporters—that relationship is changing again.

Leftists are not the only political group with a heritage of anticapitalist critique. In the long period stretching from the 1890s into the 1940s, liberal reformers also frequently articulated a bracing moral judgment of capitalism as a social system. During this half-century, many liberals and numerous leftists shared a commitment to piecemeal progress—rather than revolution—toward a fairer and more humane society.

Leftists are not the only political group with a heritage of anticapitalist critique.

To be sure, liberals compromised with powerful, even reactionary forces in order to achieve specific gains in social welfare. Not all expressed the broadly social democratic politics of Franklin Roosevelt, and virtually none questioned white supremacy until the mid thirties; even after that time many wanted to talk only about economics. Still, decades of experience with a conflict-ridden society had convinced liberals that capitalism had to be transformed to be sustainable and morally acceptable. Intellectuals were most explicit about this agenda. Louis Brandeis said in 1904 that “industrial liberty must attend political liberty” in America. Speaking of liberty, Dewey wrote in Liberalism and Social Action (1935): “Today, it signifies liberation from material insecurity and from the coercions and repressions that prevent multitudes from participation in the vast cultural resources that are at hand.” He also wrote, rather acceptingly, “Should a classless society ever come into being the formal concept of liberty would lose its significance, because the fact for which it stands would have become an integral part of the established relations of human beings to one another.” These were liberal theoreticians, not socialists.

The liberal critique of capitalism opened a wide avenue for cooperation with nonrevolutionary leftists, who rejected capitalism more definitely but wished to pursue its replacement in discrete, peaceful steps. From the 1910s through the 1940s liberal Democrats sometimes welcomed political support from socialists and other leftists rather easily; this was the great era of left-liberal collaboration in American history. Empowering organized labor and constructing a welfare state were the top items on this broad front’s shared agenda, and cooperation reached a high point in the Popular Front era of the thirties and during the wartime U.S.-USSR alliance of 1941–45, when American Communists took a reformist rather than a revolutionary stance. The Communists were moved to link arms with capitalist democrats such as Roosevelt in order to defeat fascism. Many have harshly criticized the Communists as fake liberal democrats, and Democrats for their illusions about communism. Surely there was some bad faith and wishful thinking involved, but the Popular Front was also pragmatic and productive. Groups such as the National Negro Congress, led by Ralph Bunche, the socialist A. Philip Randolph, and others, contributed to liberal politics most distinctly by injecting into it a far stauncher antiracism and commitment to civil rights than liberals would have adopted on their own. Democrats later felt vulnerable to red baiting in part because many liberals really had collaborated politically with Communists and other leftists, in significant ways.

This left-liberal alliance unraveled in the late ’40s, but Cold War liberals retained a version of their inherited anticapitalist critique. We must remember how seriously American liberals of the 1950s and 1960s took communism—and not just in international relations. The Soviets had to be repulsed not just militarily but ideologically. Facing a major world rival to the United States, an antagonist that asserted its moral supremacy based on shared criteria of human welfare, liberals strove to demonstrate the superiority of life—specifically for workers and the poor—under American capitalism.

The liberal critique of capitalism opened a wide avenue for cooperation with nonrevolutionary leftists.

Some, Humphrey perhaps most famously, also persistently championed the cause of civil rights. The Cold War compressed the political spectrum in America and foreclosed some social democratic prospects. Within these limits, however, much space for social improvement remained. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote and then published a sermon in the early 1960s titled “How Should a Christian View Communism?” arguing that Cold War liberal premises could be taken rather far toward social democracy. Acknowledging that “something in the spirit and threat of Communism challenges us,” King wrote primarily as a Christian, and he found both “traditional capitalism” and communism defective by the standard of his religious ethics. “We must honestly recognize that truth is not to be found either in traditional capitalism or in Marxism,” he wrote. Religion provided key support for Cold War anticommunism, and King’s call for a Christian synthesis of the best elements in capitalism and socialism, while daring in its time, was also a version of the Cold War liberal mission to meet the moral challenge posed by state socialism. Liberal activists at the state and local level in the 1950s and 1960s pushed against the leftward boundaries of American politics, as the scholarship of Jonathan Bell, Mark Brilliant, and Shana Bernstein on California has revealed. This forces us to complicate our understanding of Cold War liberalism. Cold War liberals, seeking to show their system’s moral superiority—from Harry Truman’s failed effort to secure a national health care system to Lyndon Johnson’s partial success in doing so with Medicare and Medicaid, to the civil rights achievements of the 1960s on which Johnson, King, and so many others collaborated—did some of the work of the left, even as the left had helped to do the work of liberalism in earlier years.

If the sometimes cooperative relationship between liberals and leftists in the first decades of the twentieth century shattered and remained broken in the two decades following World War II, the relationship between the two groups was transformed again beginning in the 1970s. At that time, liberals began turning toward a more market-oriented neoliberalism, while the left collapsed after the failure of late-sixties dreams of political transformation.

“We must honestly recognize that truth is not to be found either in traditional capitalism or in Marxism,” wrote Martin Luther King, Jr.

Neoliberals, whether those associated with the New Politics of George McGovern and Howard Dean or the somewhat more conservative New Democrats such as Michael Dukakis and Bill Clinton, tried to stitch together one more generation of a cross-class Democratic alliance. All these men deployed tactics for keeping a large chunk of white voters loyal to their party, and all were united (with intermittent heresies) by a basic political economy. Journalist and political strategist Matt Stoller has vividly etched the neoliberals’ disdain of unions and antimonopoly politics and their untroubled embrace of large-scale corporate capitalism for its admirable efficiencies. As they alternately welcomed and accommodated—rarely leading—the steady expansion of human rights in America as a priority among Democratic Party voters and donors, they also grew ever closer to the financial sector. President Jimmy Carter, elevated to power mainly by the Watergate crisis, was a neoliberal, and even Edward Kennedy, who challenged Carter’s renomination by the Democrats in 1980 in the name of Great Society liberalism, was really a hybrid figure, at that time a powerful advocate of both business deregulation and the welfare state.

Democratic neoliberals emerged from the political wreckage of the Vietnam War, but the connection between their antiwar politics and their embrace of capitalism is often overlooked. Their disillusionment with the Cold War crusade in Asia in the early ’70s and their zeal for deregulation in the late seventies were related. Consider Gary Hart, who managed McGovern’s presidential campaign in 1972 and gave Walter Mondale, the last of the real Cold War liberals and Humphrey’s protégé, a scare in the nomination contest twelve years later. When he said in 1974 that his cohort of Democrats were “not a bunch of little Hubert Humphreys,” he was rejecting a gestalt that encompassed both domestic and foreign affairs.

In many ways the neoliberals of the ’70s and ’80s were the first post–Cold War liberals. They had shed their elders’ obsession with communism abroad; hence they were antiwar. But they also no longer looked over their shoulders at a socialist moral competitor; hence they were neoliberal. The decay of communism did not readmit the left into mainstream American politics, even though the old charge of collaboration with a potent enemy state had lost its salience. Instead communism’s unwinding finally killed the old critique of capitalism within American liberalism. The neoliberals felt only contempt for the organized left. The liberals of the ’50s and ’60s had defamed the left because they feared it as a powerful but misguided response to true human needs; neoliberals now dismissed it as a puny delusion based on false claims about capitalism. In 1984 Hart ran to Mondale’s left on foreign policy and to his right on economic policy, but he was too early; not until the Soviet Union finally dissolved did a neoliberal Democrat scale the political heights.

Within the Democratic Party, well into the presidency of Bill Clinton, neoliberals fought rearguard skirmishes against old-school liberals—paleoliberals, as they are sometimes called—sincerely committed to human rights and a generous welfare state, who were living off the rapidly dissipating moral capital of the fifties and sixties. The neoliberals were the moderates in the party; certainly Bill Clinton was always a moderate. Among other things, he initiated the neoliberal re-embrace of U.S. military intervention, an innovation facilitated by the end of the Cold War, which had lost its legitimacy as a basis for hot wars among the neoliberals. Hillary Clinton was a moderate, too, but when she sought national leadership, she tried to bridge the gap between her party’s factions—failing twice to take the White House.

What is American liberalism now? Many thought that neoliberalism’s legitimacy had been crumpled by George W. Bush’s regime after it crashed and burned in Iraq, on Wall Street, in New Orleans. As Barack Obama’s administration draws to a close, that conclusion looks less secure. His campaigns were powered politically by revulsion against war and neoliberal economics, but his time in office has been characterized by accommodations to each, underwritten by a reformist philosophy of technocratic compromise. Will his days appear as a new phase of meritocratic elitism within American liberalism? Or will we see them as ending a protracted Baby Boomer phenomenon sandwiched between periods of true progressive reform? The history of Obama’s years in power will also tell the story of late-stage neoliberalism.

Obama’s campaigns were powered by revulsion to war and neoliberalism, but his time in office has been characterized by accommodations to each, underwritten by a reformist philosophy of technocratic compromise.

The left, meanwhile, has returned to prominence after an era in the wilderness of American politics. Today, opposition to war, capitalist exploitation, and white supremacy cut across both liberalism and the left. Now the left is often called progressivism, a notoriously ambiguous term. Much of it has reappeared inside the Democratic Party—a development overlooked by those who equate the left with minor parties or anti-systemic organizing. We have Bush and Sanders to thank for this reinvigoration of leftist politics inside the party system.

It was a Republican regime that perpetrated the Iraq invasion; a majority of congressional Democrats opposed it (even if many of their leaders did not). In the political and moral climate of the Iraq war, Americans desperate to set their country’s foreign policy on a new course looked to the Democrats—a striking departure from the anti-systemic bias of Vietnam-era peace activism—leading to huge Democratic victories in 2006 and 2008. There also was substantial leftist involvement in extra-party protest, but the utility of the party system as a vehicle for antiwar politics was much clearer in these years than during the Cold War.

Occupy Wall Street then erupted in 2011, giving voice to a generation teeming with outrage over stunted economic opportunity and impunity on Wall Street. Many progressives wound up criticizing the movement for failing to transfer its energies into concrete policy demands and tangible political pressure, but those did appear, belatedly, in the startling success of Sanders’s explicitly socialist calls for free public college, Medicare for all, and other Denmark-style social provisions. The Sanders campaign channeled discontent away from the anarchist impulses of Zuccotti Park and toward a statist agenda fully consonant with the broadest tradition of social democracy. The children of the Great Recession filled the halls for the old man’s speeches.

Sanders’s economism vexed some Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists and senior African Americans leaders for appearing to elevate issues of class over those of race. Conversely, the disruptions of BLM recalled the sixties for many, leading some to see it as inherently radical, despite its ideological ambiguity. (While some in BLM voiced far-reaching social critiques, many liberals and even some conservatives supported its call to curb police abuses.) The American left had structured itself for a half-century around the issues of white supremacy and empire; to some BLM seemed to fit into those familiar structures more easily than did the Sanders campaign. Though he began his political career as a civil rights organizer in the 1960s and spoke out against U.S. foreign aggression at any opportunity during the 1980s, Sanders now addressed such matters only haltingly. His majoritarian rhetoric, while thrilling to some, carried an ominous undertone for those nurtured on a politics defined by the defense of minority interests. Still, Sanders’s agenda reopened a clear path for policy collaboration between leftists and liberals, and his campaign steered a renascent social democracy inside the Democratic Party. This could turn out to be a substantial legacy.

Now President Trump looms. The coming years will offer plenty of fronts on which liberals and leftists may collaborate if they can manage it. Both groups may call themselves progressives, and for many—especially millennials—the old, rigid, Cold War–era distinction between liberal and left politics may fade. Leftist elements certainly won’t pledge undying loyalty to the Democratic Party, but the basic political fact is that today’s progressive politics, whether it succeeds or fails in securing its objectives, is already taking shape in that party and around its edges.

Trump threatens to reconfigure American politics into a face-off between an internationalist neoliberalism and a white racial nationalism.

The gravest danger to progressive politics in America is the threat of party realignment that Trump may wish to pursue—luring away a segment of the working class from the Democratic Party and driving suburbanites who embrace both neoliberal economics and multiculturalism out of the GOP. If Trump goes so far as to alienate foreign policy neoconservatives and the international trade lobby, they will go looking for a new home, and they could try to make the Democratic Party their own on a new demographic basis. If Trump reconfigures American politics into a face-off between an internationalist neoliberalism and a white racial nationalism, progressives will find themselves faced with two very bad choices. Anyone moved by either liberal or left traditions in America should make all efforts to prevent the political map being redrawn in this way.

The most promising line of attack appears to be the populist economism embraced by Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and other Democrats. The strategic value of such a gambit—not its superior social urgency—is what recommends it most strongly right now. Little else in the liberal-left repertoire promises to dislodge the expanded working-class fragment that Trump has appended to the Republican coalition or to reactivate the Democratic voters who stayed home in November. It is in the political heartland, not on the far edges of the party system, that Americans will compose the current chapters in the history of liberal and left politics.