There has been a great deal of attention to anti-Semitic demonstrations in Europe. The demonstrations in Berlin have been particularly hard to watch for those of us who are children of German Jewish refugees, and are aghast at what is happening to the people of Gaza. It is clear from Israeli social media and other sources that the demonstrations are being used as evidence of the threat Israel faces, and as support for Israel’s continued occupation of Palestinian lands and the subjugation of its people. It is worthwhile taking the time to explain why here, as so often elsewhere, the politics of hate play directly into the hands of those at whom it is directed. But first, some family history.

My father was raised in Berlin. His favorite park was Olivier Platz, in Charlottenburg; he liked the flowers, and he liked sitting on the benches. He liked watching the people go by the Kurfürstendamm from his grandparent’s balcony. Both of his parents grew up in Berlin, and loved that city dearly. They had picnics in Grunewald. My grandmother and grandfather met their friends at the Kempenski hotel. They were Germans.

Ultimately, of course, my father and his family lost everything. His grandfather, Magnus Davidsohn, was the cantor of the liberal synagogue on the Fasanenstrasse; my father watched it burn. He was beaten on the streets by thugs, beatings that gave him epilepsy. And because of a stroke of magical luck— the stroke that every survivor’s family has— in March of 1939, at the age of 6, he and my grandmother received a visa to the United States. In Germany, they were prosperous. But they arrived in New York City, in August of 1939, with nothing.

My grandfather was unable to obtain a visa to the United States. My father did not see him again for many years, they grew apart, and I never really knew my grandfather. My father and his family always harkened back to their homes in Berlin, which had been taken forcefully from them with no possibility of recompense. They had to start anew. But they never lost their love of their homeland of Germany, even though Germany had successfully expelled and murdered its Jewish citizens, and stolen their land and possessions. I understand, in this refracted way, that pain and anguish can last through many generations.

Because of this past, I have some sense of what it means to be driven out of one’s homeland and to lose everything. Unlike the Palestinians, however, my family arrived in America. For its new Jewish citizens at least, America was the land of opportunity. The Palestinians, by contrast, did not arrive in a land of opportunity. They were driven by Israel into squalid refugee camps, their lives made increasingly miserable by the country that surrounded and pressed in upon them. I am disturbed to see, on the streets where my family lost so much, words of hate chanted again. But my father raised me to see myself in the Palestinians as well.

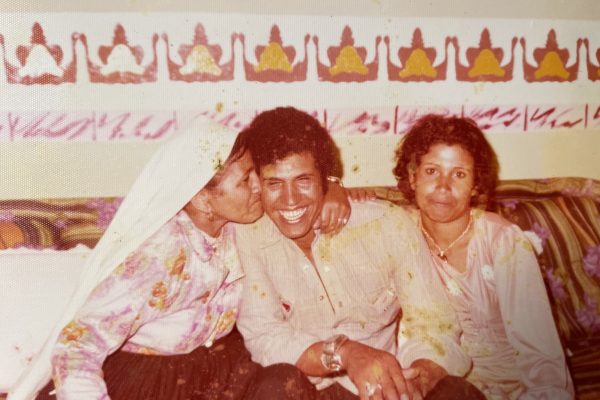

When thinking about Israel, it is useful to reflect not on his experience, but upon my mother’s. Her family is Polish. When the Germans invaded her country in 1939, her parents fled east; she was born during that flight. It was a rare combination of luck and wisdom that brought them east. There is no one on earth remaining with her maiden name. She was raised in a labor camp and met her father for the first time when she was four years old, as she traveled on the Trans-Siberian railroad back to Poland. When my father left Germany and arrived in New York, he experienced baseball, Hollywood, safety, and acceptance. But returning Jews in Poland were greeted with hatred and violence. My mother’s parents put her and my aunt in an orphanage for years, out of fear for their lives. When my grandfather was beaten almost to death on the streets of Warsaw, they received a precious visa to the United States.

I have heard those with similar family histories say this about all groups: that each group is safe only among its members. It is understandable that those who experienced what my mother and her family experienced would take away from history the lesson that everyone hates the Jews, and therefore that Jews are only safe in a nation of Jews. But this is nothing less than a repudiation of the conception of citizenship at the heart of liberal democracy. Democracy has two chief values, autonomy and equality. In a democracy, citizens have the freedom to pursue their own life paths. The choices they take cannot compromise their political equality, that is, their equality as citizens. The test of a democracy is how it allows difference to flourish; this shows that political equality does not depend upon taking a particular life-path or following certain religious beliefs. The basis for political equality is equal respect. A democracy is a state in which equal respect flourishes among its members.

A state that grants privileged status to members of one religion is not a democracy. The assumption that Israel is first and foremost a Jewish state is based upon the view that democracy is not possible. The tolerance that democracy presupposes is not possible in a state in which the culture privileges one group.

In Israel’s Declaration of Independence, its founders write that the state “will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture.” Israel fails to live up to that vision. Israel’s non-Jewish citizens have access to the ballot. But democracy is not the same as majority vote. Majority vote is not necessary for democracy—many positions in Athenian democracy were selected by lottery—and neither is it sufficient: a country in which the majority is of one ethnic group and dominates the other by majority vote lacks the political culture of a democracy. In assessing whether a state is a democracy, we must look more deeply than its method of voting.

Much ink has been spilled within Israel and beyond, disentangling the ostensible contradiction between Israel being both a democracy and a Jewish state. The residents of Gaza of course are not Israeli citizens. But history has shown time and again that it is not possible to dehumanize an enemy while treating their cousins, aunts, and uncles with equal respect. The situation is even more vexed in Israel, where the dehumanization required to maintain a permanent occupation is extreme. The oppression facing Arabs in Gaza only strengthens the skepticism within Israel about the very possibility of the creation of a pluralist multiethnic democracy based on equal rights for all.

Suppose we engage in the fantasy that Israelis could maintain equal respect for their relatives who are co-citizens while occupying and controlling the economic and material resources of foreign citizens within its territory. Even then, Israel would at best be hypocritical in depriving millions of Palestinians of their democratic rights.

Despite all of this, Israelis invested in the democratic nature of their state remain hopeful that in the future there might be a firmer separation between religion and state that would still maintain the Jewish character of the state. Think of Anglicanism in England or Catholicism in Spain. This would not privilege any particular religion over any other but would still lend Jewish character to the state. For example, federal holidays would be Jewish holidays, like Christmas in many liberal democracies. Right now, that ideal seems very distant from reality.

But it is possible, with the space of generations, to reclaim the attitudes of a democratic citizen. Despite my family history, I have returned to my father’s homeland many times, sometimes for years. I have absorbed its language, literature, and philosophy, and experienced the love of Germany that my father’s family never lost. I am able to do so even knowing that I have close friends whose grandparents not only participated in the murder of my people, but feel no remorse whatsoever about it. I love Germany, despite having been told by older Germans that what the Jews did to Germany after World War II is far worse than what Germany ever did to Jews. I have broken bread with former Nazis, and have close friends who were raised steeped in anti-Semitism, and have shaken off those shackles. I am acutely aware of the terror my father felt on the streets of Berlin. Nevertheless, walking those streets, I can still feel the echo of my ancestors’ footsteps, and turn corners to discover places where I imagine they experienced their first kiss.

I know it is possible that one day the descendants of today’s Palestinian refugees will again be able to go to Tel Aviv or Jerusalem and walk the streets of the cities of their grandparents, together in friendship with the grandchildren of those who now oppress them, past houses that may rightfully belong to them.

However, when I see people standing on the streets of what once was the capital city of Nazi Germany repeating the slogans of the past, even I experience seeds of doubt. Perhaps I am naïve to believe in the democratic ideals of autonomy, equality, and tolerance. Perhaps life is just war between different religions. Worse yet, when people stand on the streets of Hitler’s capital, which symbolizes for so many the failures of democratic idealism, and call for the destruction of the Jews, they strengthen the hand of those who call for no mercy for the enemy. They make themselves complicit in the bombs that land on hospitals and schools.