The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman

Norton, $27.95 (cloth)

The crowd at Elizabeth Warren’s rally in New York City in September was enthusiastic throughout, but it was her proposed new wealth tax—2 percent on wealth above $50 million, rising to 3 percent above $1 billion—that got them chanting: “Two cents! Two Cents! Two Cents!” Bernie Sanders has proposed a similar wealth tax, with rates peaking at 8 percent above $5 billion. In the October Democratic debate, a number of centrist candidates were open to it, and even Joe Biden, who seemed to reject one, argued for eliminating the favorable tax treatment of capital gains and raising income tax rates for the rich.

In tying their advocacy so closely to the shape of tax burdens, instead of to overall welfare outcomes, Saez and Zucman focus on the wrong question.

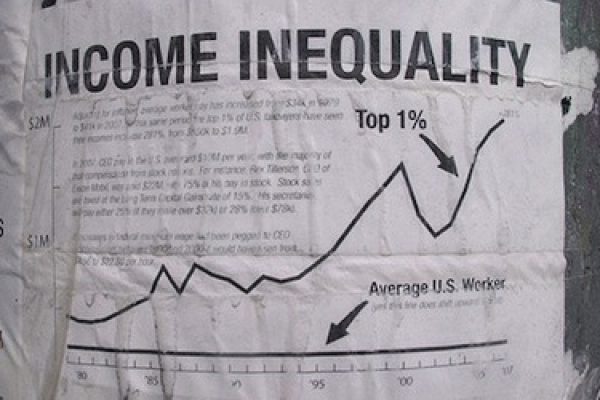

Democratic presidential candidates used to be far less comfortable about advocating higher taxes, let alone proposing an entirely new one. The dramatic transformation of America’s tax system that has brought us to this point is told in Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman’s important and accessible new book, The Triumph of Injustice. Drawing on their own technical work in economics, the authors present a detailed picture of the distribution of income and wealth in the United States over the last century, along with the history of taxation in all its forms—federal income, corporate, payroll, and estate taxes, as well as state and local income and consumption taxes. Thanks to a flurry of new economic research on inequality in recent years, the basic arc of this transformation is familiar: income and wealth inequality have increased dramatically, while marginal income and corporate taxes have fallen significantly from their highest rates. The two developments, Saez and Zucman contend, are not a coincidence.

Despite all this, the book is optimistic. It is not a dispassionate, normatively neutral presentation of a set of options for policy makers to choose from; economists do not usually use words like “injustice.” This is a piece not just of policy analysis but of policy advocacy, timed no doubt for the 2020 election cycle.

Some will read the book as nothing more than a how-to guide for soaking the rich. But in addition to its economic analysis, the book contains the elements of a powerful vision of economic justice. Still, there is an unfortunate mismatch between that vision and the way the authors lay out their argument. Their headline claim is that the U.S. tax system is no longer progressive: the rich no longer pay more than the rest of us, as a percentage of their income.

Some will read the book as nothing more than a how-to guide for soaking the rich. But it contains the elements of a powerful vision of economic justice.

But in tying the moral force of their advocacy so closely to the issue of the shape of the tax distribution, instead of to overall welfare outcomes, Saez and Zucman focus on the wrong question and risk playing into the hands of the market fundamentalists they oppose. The moral demands of distributive justice do not compel us to implement this or that particular form of taxation. What matters is how well the tax system promotes just outcomes, all government services considered. Progress on economic justice will not be made by pretending—even for the sake of argument—that there is an entirely separate issue of tax fairness. Instead, we must challenge head-on the market fundamentalism that insists on that, precisely in order to shut down any discussion of just welfare outcomes.

The book weaves together three distinct arguments: a descriptive analysis of the transformation of our tax system, a series of policy recommendations about how to fix it, and an implicit normative theory of economic justice. Let’s take these in turn.

Consider the current numbers. The 2019 federal income tax, taken on its own, is progressive—effective tax rates rise with income. But U.S. residents also pay federal payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare as well as state and local taxes. Looking to this total tax paid as a percentage of income, Saez and Zucman reach the startling conclusion that we now have essentially a flat tax of around 28 percent. In fact, within the top 1 percent income group the average rate first rises a few points above that but then falls, so that the 400 richest Americans pay an average rate of 23 percent. When Dwight Eisenhower was president, by contrast, the top 0.1 percent income earners paid an average tax rate of 55 percent, while the average rate for the bottom 90 percent was about 20 percent. The home page of the authors’ website, taxjusticenow.org, features an animated graph illustrating the decline in progressivity since 1950.

The U.S. tax system is no longer progressive: the rich no longer pay more than the rest of us, as a percentage of their income.

Some commentators have criticized Saez and Zucman for ignoring government transfers, in particular the refundable Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. President Obama’s former economic advisor Jason Furman, for example, argues that we should count cash transfers against the tax burden of those who receive them—as the Congressional Budget Office does in its estimates—since there is no difference, from the point of view of a person’s welfare, between a tax reduction and a transfer. Because most cash transfers go to low income families, the resulting distribution of tax burdens would be more progressive than The Triumph of Injustice makes it seem, at least at the low end. But why, the authors reply, should we count the benefits of cash transfers but not the rest of government spending, such as defense? (See the Twitter exchange between Furman and Zucman, and the FAQ on the authors’ website.) In a limited sense, I think Saez and Zucman have the better of this issue. Once we start to count benefits from the government, we have to count the whole lot: defense, the police, the legal system, public education, public hospitals, and so on. It is tendentious to count just means-tested cash transfers that go to lower income earners only. What about the cost of airport security, which benefits mostly the better off?

On the other hand, these reflections inevitably lead us to the conclusion that distributions of tax burdens, though of great pragmatic significance to policy makers, are always potentially misleading when discussing justice in taxation. It is tendentious to count only some transfers, but it is also true that what matters is the net effect of the entire set of legal and economic institutions, government spending included, not just the tax burden. In their FAQ, Saez and Zucman write: “How transfers are distributed is certainly an important question but our website is about taxes.” That may be, but we cannot directly draw conclusions about justice from the distribution of taxes alone. Justice in taxation is not a matter of some fair distribution of tax burdens as measured against pretax income. It is about how well or badly the tax system, together with the other elements of the economic and welfare system, secures just results, which is a matter of absolute and relative levels of welfare, the absence of social stratification and concentrations of power, and so on. Even if Saez and Zucman are right that we now have a flat effective tax rate, that is not necessarily a sign of unfairness or injustice. Such a tax scheme, coupled with very significant cash grants, could in principle be part of an overall just approach. The distribution of tax burdens is important only insofar as it is informative for policy makers thinking about how taxes can play their part in overall social policy aimed at making our society more just.

Justice in taxation is not a matter of some fair distribution of tax burdens. It is about how well or badly the tax system secures just results.

The same goes for the distribution of pretax income. Saez and Zucman show that since around 1980 income inequality has dramatically increased, with the income share of the top 1 percent doubling to around 20 percent, and that of the bottom 50 percent almost halving, to around 12 percent. It is striking that despite having published (together with Thomas Piketty) what seems to me to be profoundly important work on how to measure the distribution of post-tax income (taking into account taxes and all government spending), Saez and Zucman mention post-tax distribution only once in the book. They indicate, in passing, that it is a little less unequal than the pre-tax distribution, mainly because of Medicare and Medicaid. This is good information to have, since if the post-tax distribution were vastly better from the point of view of equality than the pretax distribution, it would clearly be misleading to point to the pretax distribution as a source of injustice.

But unconsumed wealth contributes to welfare too and so the distribution of wealth is also important. Once more, the story is grim: since the late 1970s the wealth share of the top 1 percent has grown from 22 percent to 37 percent, while that of the bottom 90 percent has declined from 40 percent to 27 percent.

Economists have and will continue to question some of Saez and Zucman’s particular claims. But no one can deny that over the past half-century or so inequality of post-tax income and wealth, and thus inequality of welfare, has greatly increased and that the position of those at the bottom end of the distribution is getting harder in absolute terms. (Saez and Zucman rightly emphasize the significance of falling life expectancy for the poor in the United States.) The issue is what government should do about this, and what role taxes should play. There are really three questions. First, what, pragmatically, given constraints on feasible institutional design for a global economy, can taxation and transfer achieve by way of addressing poverty and inequality? Second, what does justice demand, given that set of feasible options? Third, what, in a democracy, is politically feasible?

This takes us to second component of the book, their policy recommendations. The main cause for the decreasing progressivity of the U.S. tax system identified by Saez and Zucman, in addition to the obvious one of the lowering of marginal rates for higher income brackets, has been the trend toward favorable tax treatment of capital rather than labor income. The effect is anti-egalitarian, since the rich get more of their income from capital than the poor do. The move to favorable treatment of capital income has typically been justified as a stimulus to investment that is good for everyone, workers included—the rising tide that lifts all boats. But whatever the economic models say, the empirical evidence does not support this argument. As Saez and Zucman tell us: “Over the last hundred years, there is no observable correlation between capital taxation and capital accumulation.”

There is too much hand-wringing, they suggest, about how to effectively tax capital. There are things we can do, if we only have the will.

There are a number of elements to the differential tax treatment of capital income. Long-term capital gains and dividends are taxed at a lower rate than wage income. And if corporate profits are not distributed to shareholders as dividends but instead reinvested into the company, there is an increase in shareholders’ wealth that is not subject to income tax. This is where the corporate tax comes in, as it taxes corporate profits even if they are not distributed as dividends. As Saez and Zucman remind us, “only people pay taxes”; the justification of the corporate tax is to get at increases in individuals’ wealth that is not captured by the income tax. But the highest corporate tax rate has decreased from around 50 percent in the middle of the last century, to 35 percent in 1994, to 21 percent in 2018. If you keep in mind that there is no observable correlation between capital taxation and capital accumulation—and thus no welfare-based justification for this more and more favorable treatment of capital income—it is hard to see all this as anything but a massive redistribution from poor to rich.

But of course the situation is worse still, because of global tax competition and the use of shell companies in tax havens to hide income. U.S. residents must pay tax on worldwide income, so the latter practice is simply illegal; the issue is enforcement. Here progress was made in 2010 with the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FACTA) that requires foreign banks to inform the IRS of accounts held by U.S. citizens, on pain of a penalty applied to U.S.-sourced payments to the bank.

Global tax competition, however, allows corporations to avoid paying U.S. taxes by maneuvers that are in principle entirely legal. The simplest way it can work is that a U.S. corporation could relocate all its activity, all its capital, to a low tax country. Saez and Zucman show, however, that this is not the most important way corporations make use of lower rates in other jurisdictions. Shifting income to another place is mostly a matter of paper profits rather than real economic activity. A multinational corporation—Apple, say—books a disproportionate amount of its profits in a low tax country, say Ireland. This should be no advantage to Apple in theory, since it is required to sell to its Irish subsidiary at a “transfer price” pegged to the market. Saez and Zucman explain how transfer pricing is manipulated in practice to keep profits low in high tax countries.

We need a progressive wealth tax, they argue, because even with other reforms, the wealthiest Americans would receive too little taxable income.

Is there anything like FACTA that can take care of this profit-shifting problem? The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did impose a minimum tax on foreign profits of U.S. multinational corporations. But Saez and Zucman make a bolder proposal. They define “tax deficit” as the difference between the tax a U.S. corporation pays in, say, Bermuda, to what it would pay in the United States. What they call “remedial taxes” could be levied by the United States to make up the deficits. Apparently the information necessary for such a tax is now available to the IRS through reporting requirements. Surely the result would be that corporations would respond by expatriating in fact, rather than just on paper? Saez and Zucman think that the specter of so called inversions—U.S. companies merging with companies in tax havens in order to move their tax home—is greatly exaggerated. The more serious risk is tax competition among economically significant countries. Here they propose coordination among the G20 countries, suggesting that mutual self-interest will be effective among this group. Perhaps. There is also the possibility of cooperation among “anti-globalist” leaders to ensure that oligarchs remain safe from taxation anywhere. In any event, Saez and Zucman have a mop-up proposal to deal with inversions and failures of coordination among the big economies: countries can impose remedial taxes based on sales within their borders.

Overall, then, their suggestion is that we should stop the hand-wringing about how we can effectively tax capital in the face of global financial mobility and tax competition. There are things we can do, if we only have the will. They estimate that for the top 1 percent the optimal average tax rate is 60 percent—optimal in the sense that a higher rate would fall on the wrong side of the point at which higher taxes would generate less revenue by deterring work. (This relationship, represented graphically by the Laffer curve, has been put to effective ideological use by proponents of lower taxes.)

But suppose that they are right, and suppose too that all the proposals discussed thus far are feasible. We solve the problem of global tax competition. We tax capital income the same as labor income. We get the government to invest more resources in policing avoidance. We also, of course, raise the marginal tax rates. Even after all that, they argue, we cannot easily achieve the optimal average tax rate at the high end. We need a progressive wealth tax.

Why? Because the very wealthiest Americans receive too little taxable income. The corporate tax is too crude an instrument to catch untaxed increases in wealth because it is not progressive at the taxpayer level. What about the estate tax or a new progressive inheritance tax? We have to tax the super wealthy now, the authors reply, and some of them are very young! And so the authors propose a wealth tax—the one publicized by Senator Warren, whom they have advised. (There is, in fact, another option, embraced by Democratic candidate Julián Castro among others, which is to tax capital income as it accrues—taxing gains in the market value of assets annually rather than only upon selling them. For discussion of this point, see an essay by the legal scholars Lily Batchelder and David Kamin.)

There has been pushback on Saez and Zucman’s claims about how much revenue a wealth tax could raise, most notably by former Obama adviser and Clinton Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and his coauthor Natasha Sarin, a professor at Wharton and the University of Pennsylvania Law School, who argue the wealth tax will generate much less revenue than Saez and Zucman estimate. Saez and Zucman have replied. Either way, there can be no doubt that a progressive wealth tax would have a significant impact on high end wealth.

This brings us, last, to their normative theory of justice. Saez and Zucman are economists, not political theorists, yet they clearly have a political vision. What is it, exactly, that leads them to claim that “injustice” has triumphed?

Saez and Zucman are not strict egalitarians. They embrace a version of the Rawlsian idea that we should most benefit the worst-off group.

They never make their conception of justice fully explicit, but it is possible to discern a few features. My sense is that their view of the market is one that I share: its moral value lies entirely in its superiority to alternatives in promoting overall welfare and (I would add) its compatibility with individual liberty. There is no moral significance to the particular allocation of rewards a purely laissez-faire market would produce and in fact, for markets to be compatible with justice, they have to be carefully regulated so as to avoid laissez-faire outcomes.

The foes of this view—proponents of libertarianism, or “market fundamentalism,” as Saez and Zucman call it—hold that pretax incomes are just precisely because they result from market exchange. There are two versions of this idea. One appeals to some natural moral entitlement to property, so that whatever property I end up with after free exchange simply belongs to me. The other appeals to some notion of just reward, or desert, so that I am entitled to the results of market exchange because I deserve them. Each view is subject to strong objections. One that applies to them both is that pretax market returns are not, in fact, ideally competitive free-market returns, but market returns earned in an economy shaped by all kinds of government policy, taxation included. Pretax income can’t be used as a baseline because it is, in fact, an output of the very system (taxation and all the rest) we are trying to make just.

Economic justice is about outcomes, then, but what are just outcomes? As I read them, Saez and Zucman are not strict egalitarians. Rather, they embrace a version of the Rawlsian idea that we should choose from among feasible sets of institutions the one which most benefits the worst-off group. On this view, the reason to tax the rich more highly is just that that’s where the money is—it’s the way to maximize revenue.

Saez and Zucman are strangely uninterested in the role of inheritance in maintaining socially harmful inequalities.

In a suggestive chapter titled “Beyond Laffer,” however, the authors make a case for taxing the rich even at the expense of revenue. The idea here is not that economic inequality is a moral evil that should be tackled even if no one benefits. Rather, the problem with inequality is that it has instrumentally bad effects. They gesture at its familiar implications for political power, but they do not go further and discuss, for example, whether economic inequality might lead to objectionable kinds of social stratification. Overall, this chapter could have benefitted from acquaintance with some of the philosophical literature on inequality, such as T. M. Scanlon’s recent book, Why Does Inequality Matter?

But as economists, they do make an interesting contribution to the issue of the grounds for reducing inequality. Their suggestion is that a more equal distribution in a market economy leads to better economic outcomes for the worse-off, entirely independently of transfers; the trickle-down theory is the reverse of the truth. Thus, a view of justice that does not object to economic inequality as such, but rather prioritizes benefits to the worse off, can favor reducing high-end incomes with no revenue gain because, in practice, it will still make the worse off better off. I don’t know whether this is true, but if they are right, this would be another powerful instrumental reason to reduce inequality. In this connection they consider the effects of what they call a “radical” wealth tax, with a marginal rate of 10 percent above $1 billion.

Despite all this, Saez and Zucman are strangely uninterested in the role of inheritance in maintaining socially harmful inequalities. They do note the steady erosion of the estate tax over recent decades and hardly regard it as a good thing. But in a comprehensive treatment of the options for fundamental reform, the lack of discussion of the role of gratuitous transfers—gifts and bequests—is surprising. There are a number of issues. For one thing, there seems to be no reason not to include large gratuitous receipts in the recipient’s taxable income. Second, if we want a separate additional tax on large bequests, an inheritance tax seems superior to an estate tax: what matters is not the size of an estate, but how much individuals benefit from transfers. In any case, the fact that Mark Zuckerberg is so young—and thus we cannot afford to wait until he dies—seems hardly a sufficient reason for putting the entire issue of dynastic wealth to one side.

Perhaps the reason for this neglect is the evident unpopularity of taxes on bequests. But then the “radical” wealth tax that Saez and Zucman propose seems unlikely to be wildly popular either. Senator Warren makes no mention of such a radical tax, and even what Senator Sanders proposes is considerably less aggressive. If political viability is driving the analysis, it is not obvious that intuitive arguments in favor breaking up dynasties could not gain some traction.

What about the rest of what Saez and Zucman propose: does any of it have a chance of garnering majority support? There appears to be very considerable support for attacking the low tax rates paid by the richest Americans. This support no doubt explains why Saez and Zucman mainly discuss the distribution of tax burdens even though, on the moral view they evidently embrace, this distribution is not what matters. They want to make the argument in a way that shocks the conscience even of those who believe that there is inherent moral value in market outcomes.

In the long run, the more important strategy is to counteract “everyday libertarianism,” which insists pretax income is deserved.

But I am not sure that this strategy is the best one. In the long run, the important thing is to counteract the widespread “everyday libertarianism”—as Thomas Nagel and I call it in our book The Myth of Ownership: Taxes and Justice—that insists in some vague but nonetheless stubborn way that pretax returns belong to us or are deserved, with the direct implication that taxes, in their very definition, take away what is rightfully ours and so are inherently morally suspect. Until we stop thinking that way, public political discussion about economic justice will fail to be about what really matters.

Saez and Zucman write at various points that an effective tax system requires more than good laws and good enforcement. We need people to embrace a “belief system,” a moral outlook, that supports the aims of just economic policy. This is obviously also necessary for democratic viability. The best way to contribute to a better moral understanding is not to pull punches on the right way to understand the moral significance of the market—and the proper place of taxes as just one instrument in the total set of economic institutions that can bring about a just society.